TFC Circulation

JTS / CoTCCC

Introduction

After completing the Airway and Respiration portion of Tactical Field Care, the next focus is on Circulation.

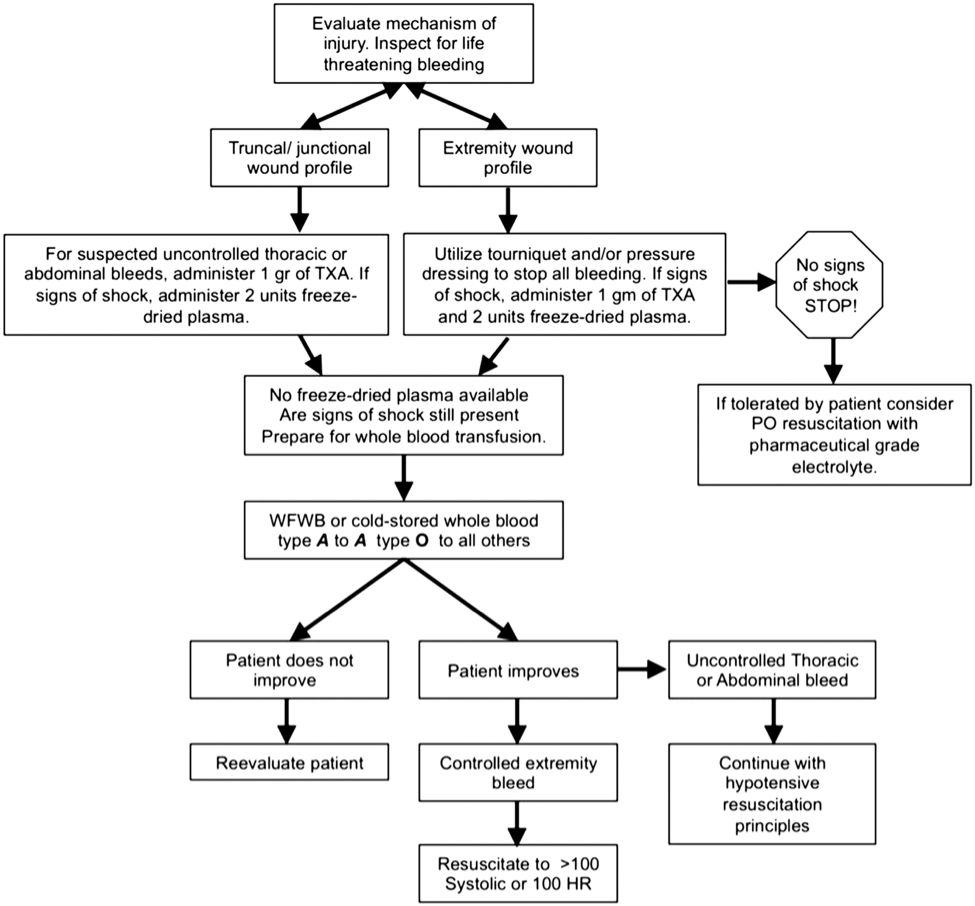

The Circulation portion of Tactical Field Care consists of determining if a patient is in shock, and if they need intravenous (IV) access. Not all casualties need IVs. The intravenous and intraosseous routes and suggested indications and techniques are discussed. The proper use and administration of tranexamic acid (TXA) is also discussed as an adjunct to help reduce blood loss from internal hemorrhage. The concepts and suggested types of fluids for resuscitation are also discussed, including the use of blood and blood products if available, and the avoidance of over-resuscitation.

Objectives

Videos

Guidelines and Key Points

Intravenous (IV) access

Intravenous (IV) or intraosseous (IO) access is indicated if the casualty is in hemorrhagic shock or at significant risk of shock (and may therefore need fluid resuscitation), or if the casualty needs medications, but cannot take them by mouth.

- An 18-gauge IV or saline lock is preferred.

- If vascular access is needed but not quickly obtainable via the IV route, use the IO route.

NOT ALL CASUALTIES NEED IVS!

DO NOT start IVs on casualties who are unlikely to need fluid resuscitation or IV medications. Do not use for minor injuries as it wastes supplies, takes too much time, and can distract from other more important care or tactical concerns.

The indications for IV access are:

- Fluid resuscitation for hemorrhagic shock or significant risk of shock such as a gunshot wound to the torso.

- The need to give medications but the casualty is unable to swallow, is vomiting, or has a decreased state of consciousness.

DO NOT insert an IV distal to a significant wound! An IV lock is recommended instead of an IV line unless fluids are needed immediately. Flush IV lock with 5cc NS (normal saline) immediately and then every 1-2 hours to keep it open.

Tranexamic Acid (TXA)

If a casualty is anticipated to need significant blood transfusion (for example: presents with hemorrhagic shock, one or more major amputations, penetrating torso trauma, or evidence of severe bleeding):

- Administer 1 gram of Tranexamic Acid in 100 mL Normal Saline or Lactated Ringers as soon as possible but NOT later than 3 hours after injury. When given, the TXA should be administered over 10 minutes by IV infusion.

- Begin second infusion of 1 gm TXA after Hextend or other fluid treatment.

Tranexamic Acid (TXA) helps to reduce blood loss from internal hemorrhage sites that can't be addressed by tourniquets and hemostatic dressings.

Tourniquets and Combat Gauze do not work for internal bleeding, TXA does!

Survival benefit of TXA is GREATEST when given within 1 hour of injury. Give it as soon after wounding as possible! But DO NOT GIVE TXA if more than 3 hours have passed - survival is DECREASED if TXA is given after 3 hours.

Possible side effects of TXA include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, visual disturbances and hypotension if given as a bolus. Do not be deterred by possible side effects. The important thing is to stop the bleeding and save the casualty’s life.

TXA should NOT be given with Hextend or through an IV line with Hextend in it. Infuse slowly over 10 minutes. Rapid IV push may cause hypotension. If there is a new-onset drop in BP during the infusion - SLOW DOWN the TXA infusion then administer blood products or Hextend.

Fluid Resuscitation

1. The resuscitation fluids of choice for casualties in hemorrhagic shock, listed from most to least preferred, are:

- Whole blood*

- Plasma, red blood cells (RBCs) and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio*

- Plasma and RBCs in a 1:1 ratio

- Plasma or RBCs alone

- Hextend

- Crystalloid (Lactated Ringers or Plasma-Lyte A)

2. Assess for hemorrhagic shock (altered mental status in the absence of brain injury and/or weak or absent radial pulse).

NOTE: Hypothermia prevention measures (See Hypothermia Pocket Guide) should be initiated while fluid resuscitation is being accomplished.

If not in shock:

- No IV fluids are immediately necessary.

- Fluids by mouth are permissible if the casualty is conscious and can swallow.

If in shock and blood products are available under an approved command or theater blood product administration protocol:

- Resuscitate with whole blood*, or, if not available;

- Plasma, RBCs and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio*, or, if not available;

- Plasma and RBCs in 1:1 ratio, or, if not available;

- Reconstituted dried plasma, liquid plasma or thawed plasma alone or RBCs alone;

- Reassess the casualty after each unit. Continue resuscitation until a palpable radial pulse, improved mental status or systolic BP of 80-90 is present

If in shock and blood products are not available under an approved command or theater blood product administration protocol due to tactical or logistical constraints:

- Resuscitate with Hextend, or if not available;

- Lactated Ringers or Plasma-Lyte A;

- Reassess the casualty after each 500 mL IV bolus;

- Continue resuscitation until a palpable radial pulse, improved mental status, or systolic BP of 80-90 mmHg is present.

- Discontinue fluid administration when one or more of the above end points has been achieved.

Shock is inadequate blood flow to the body tissues. Shock can have many causes, but on the battlefield, it is typically caused by severe blood loss. Hemorrhagic shock is the leading cause of preventable death on the battlefield. REMEMBER! The most reliable signs of shock on the battlefield are: A decreased level of consciousness (without TBI) and/or a weak or absent radial pulse.

The first step in fluid resuscitation is to assess for shock. If not in shock, no IV fluids are necessary but fluids by mouth are permissible. If in shock and blood products are available, transfuse with the best available products.

If blood products are not available, transfuse with Hextend or crystalloid. Hextend is preferred over crystalloid because the volume needed is less, and it lasts longer.

Do not pause between units of resuscitation fluids. Reassess after each unit of blood product or 500 cc of Hextend or crystalloid. Continue until a palpable radial pulse, improved mental status or systolic BP of 80-90 is achieved.

Shock increases mortality in casualties with head injuries, so you have to be more aggressive with your fluid resuscitation. Resuscitate until there is a NORMAL, not just palpable, radial pulse, or a systolic BP of at least 90.

If a casualty with an altered mental status due to suspected TBI has a weak or absent peripheral pulse, resuscitate as necessary to restore and maintain a normal radial pulse. If BP monitoring is available, maintain a target systolic BP of at least 90 mmHg.

Reassess the casualty frequently to check for recurrence of shock. If shock recurs, recheck all external hemorrhage control measures to ensure that they are still effective and repeat the fluid resuscitation as outlined above.

The goal of fluid resuscitation is NOT to restore a normal blood pressure. The goal of fluid resuscitation is an improved state of consciousness or palpable radial pulse, corresponding to a systolic blood pressure of 80 to 90 millimeters mercury.

If the blood pressure goes up too much, this may interfere with the body’s attempt to clot or disrupt a clot that has formed, essentially “popping the clot.”

Also remember to initiate hypothermia prevention measures while fluid resuscitation is being accomplished.

Hypotensive Resuscitation Saves Lives in Non-Compressible Hemorrhage! DO NOT start your fluid resuscitation by giving two liters of LR or NS wide open before re-assessing your casualty!

REMEMBER! If the casualty is not in shock, don’t use your IV fluids.

SAVE IV FLUIDS FOR CASUALTIES WHO REALLY NEED THEM. The next person to get shot may die if he or she doesn’t get fluids.

*Currently, neither whole blood nor apheresis platelets collected in theater are FDA-compliant because of the way they are collected. Consequently, whole blood and 1:1:1 resuscitation using apheresis platelets should be used only if all of the FDA-compliant blood products needed to support 1:1:1 resuscitation are not available, or if 1:1:1 resuscitation is not producing the desired clinical effect.

If a casualty in shock is not responding to fluid resuscitation, consider untreated tension pneumothorax as a possible cause of refractory shock. Thoracic trauma, persistent respiratory distress, absent breath sounds, and hemoglobin oxygen saturation < 90% support this diagnosis. Treat as indicated with repeated NDC or finger thoracostomy/chest tube insertion at the 5th ICS in the AAL, according to the skills, experience, and authorizations of the treating medical provider. Note that if finger thoracostomy is used, it may not remain patent and finger decompression through the incision may have to be repeated. Consider decompressing the opposite side of the chest if indicated based on the mechanism of injury and physical findings.

Summary

The Use of Pelvic Binders in TCCC

The Use of Pelvic Binders in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 1602.

Col Stacy Shackelford, MD; Rick Hammesfahr, MD; MSG (Ret); MSG Daniel Morissette, SO-ATP; Harold Montgomery, SO-ATP; Win Kerr, SO-ATP; CAPT (Ret) Brad Bennett, PhD, NREMT-P; Col (Ret) Warren Dorlac, MD; CAPT Stephen Bree, MD; CAPT (Ret) Frank Butler, MD

Journal of Special Operation Medicine 2017 (1) 135-147

Pelvic fractures can result in massive bleeding and death. Dismounted improvised explosive device (IED) attacks, gunshot wounds and motor vehicle accidents often result in pelvic fractures. IED attacks have been the major cause of combat related injuries during the Afghanistan conflict. “Twenty-six percent of service members who died during Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom had a pelvic fracture.” For these reasons, the CoTCCC conducted an extensive review of the literature which led to the addition of pelvic binders to the TCCC guidelines.

- Emergent treatment options for pelvic fractures include pelvic binder, external fixation, internal fixation, direct surgical hemostasis, preperitoneal pelvic packing, and pelvic angiography and embolization. Of these, the only treatment available to prehospital providers is the pelvic binder.

- Although definitive evidence demonstrating improved survival with pelvic binder use is lacking, the existing evidence addressing the management of pelvic hemorrhage recommends pelvic binder use for initial management of pelvic fracture hemorrhage.

- Placement of the binder at the level of the pubic symphysis and greater trochanters was shown to reduce the unstable pelvic fracture most effectively with the least amount of force.

- It is more likely that splinting of pathologic fracture motion allows clot formation and is the mechanism that aids in hemostasis.

- Hemorrhage with stable fracture patterns is unlikely to be controlled with a pelvic binder. However, since it is not possible to differentiate a stable from an unstable fracture pattern in the prehospital environment, all suspected pelvic fractures should have a binder applied.

- Applying a pelvic binder is unlikely to increase injury or bleeding. Prolonged use or overtightening may cause pressure ulcerations.

- A pelvic binder should be applied for cases of suspected pelvic fracture in severe blunt force or blast injury with one or more of the following indications:

- Pelvic pain

- Any major lower limb amputation or near amputation

- Physical exam findings suggestive of a pelvic fracture

- Unconsciousness

- Shock

- There is very weak evidence to suggest that a commercial device is more effective in controlling hemorrhage than an improvised sheet. There is no evidence that any commercial compression device is better than another.

Take Home Message:

Fluid Resuscitation for Hemorrhagic Shock in TCCC

Fluid Resuscitation for Hemorrhagic Shock in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 14-01 -2 June 2014

Frank K. Butler, MD; John B. Holcomb, MD; Martin A. Schreiber, MD; Russ S. Kotwal, MD; Donald A. Jenkins, MD; Howard R. Champion, MD, FACS, FRCS; F. Bowling; Andrew P. Cap, MD; Joseph J. Dubose, MD; Warren C. Dorlac, MD; Gina R. Dorlac, MD; Norman E. McSwain, MD, FACS; Jeffrey W Timby, MD; Lorne H. Blackbourne, MD; Zsolt T. Stockinger, MD; Geir Strandenes, MD; Richard B, Weiskopf, MD; Kirby R. Gross, MD; Jeffrey A. Bailey, MD

Journal of Special Operations Medicine. 2014 Fall;14(3):13-38.

This article discusses changes in the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines that are based on a review of the literature on fluid resuscitation in hemorrhagic shock. The evidence extracted from the literature review was applied to the resuscitation of combat casualties in the prehospital environment and used to develop updated TCCC fluid resuscitation guidelines.

- Order of precedence for resuscitation fluid options:

- Whole blood

- 1:1:1 plasma, Red Blood Cells (RBCs), and platelets

- 1:1 plasma and RBCs

- Reconstituted Dried Plasma,liquid plasma, or thawed plasma alone or RBCs alone

- Hextend

- LR or Plasma-Lyte A

** Normal Saline (NS) is not recommended for hemorrhagic shock, but may be indicated for dehydration.

- Dried plasma (DP) is added as an option when other blood components or whole blood are not available.

- Hextend is a less desirable option than whole blood, blood components, or DP and should be used only when these preferred options are not available.

- 1: 1: 1 damage control resuscitation (DCR) is preferred to 1:1 DCR when platelets arc available as well as plasma and red cells.

- The 30-minute wait between increments of resuscitation fluid administered to achieve clinical improvement or target blood pressure (BP) has been eliminated.

- The volume of fluid used in the resuscitation of casualties in hemorrhagic shock is an important factor in determining outcomes. The optimal volume may vary based on the type of injuries present, but large-volume crystalloid fluid resuscitation for patients in shock caused by penetrating torso trauma has been shown to decrease patient survival compared with resuscitation with restricted volumes of crystalloid.

- Hextend may decrease complications of crystalloid resuscitation such as ARDS and ACS, but does not decrease the dilutional coagulopathy caused by crystalloid resuscitation.

Take Home Message:

Emergency Whole-Blood Use in the Field

Emergency Whole-Blood use in the Field: A Simplified Protocol for Collection and Transfusion

Geir Strandenes, Marc De Pasquale, Andrew P. Cap, Tor A. Hervig, Einar K. Kristoffersen, Matthew Hickey, Christopher Cordova, Olle Berseus

Combat medics need proper protocol-based guidance and education if whole-blood collection and transfusion are to be successfully and safely performed in austere environments. This article presents the Norwegian Naval Special Operation Commando unit specific remote damage control resuscitation protocol, which includes field collection and transfusion of whole blood as an example that can be used as a template to develop unit specific protocols.

- Resuscitation in the field with a full complement of RBCs, plasma, and platelets may offer an advantage, especially under conditions where evacuation is delayed.

- No current evacuation system, military or civilian, can provide RBC, plasma, and platelet units in a prehospital environment, especially in austere settings.

- Military experience and laboratory data provide a rationale for whole-blood use in the treatment of massive hemorrhage.

- As a result, for the vast majority of casualties, in austere settings, with life-threatening hemorrhage, it is appropriate to consider a whole blood based resuscitation approach to reduce the risk of death from hemorrhagic shock.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message

Warm Fresh Whole Blood Transfusion Associated With Improved Survival

Warm Fresh Whole Blood is Independently Associated with Improved Survival for Patients with Combat-Related Traumatic Injuries

Philip C. Spinella, MD, Jeremy G. Perkins, MD, Kurt W. Grathwohl, MD, Alec C. Beekley, MD, and John B. Holcomb, MD

The authors of this article examined the possibility that warm fresh whole blood (WFWB) transfusion would be associated with improved survival in patients with traumatic injuries compared with those transfused with only stored component therapy (CT). They retrospectively looked at US Military combat casualty patients transfused >1 unit of red blood cells (RBCs), and compared two groups of patients:

- WFWB, who were transfused WFWB, RBCs, and plasma but not apheresis platelets.

- CT, who were transfused RBC, plasma, and apheresis platelets but not WFWB.

- Both 24-hour and 30-day survival were higher in the WFWB cohort compared with CT patients.

- An increased amount (825mL) of additives and anticoagulants were administered to the CT compared with the WFWB group.

- Upon further statistical analysis, the use of WFWB and the volume of WFWB transfused was independently associated with improved 30-day survival.

- In a subset analysis, the data indicated that as time progressed and capabilities improved at combat support hospitals that the relationship between improved survival and WFWB use remained and was not influenced by this factor.

READ FULL PDF