TFC Respiration / Chest Trauma

JTS/CoTCCC

Introduction

Tactical Field Care is the care rendered by the first responder or combatant once no longer under effective hostile fire. It also applies to situations in which an injury has occurred, but there has been no hostile fire. Available medical equipment is still limited to that carried into the field by unit personnel. Time to evacuation to a medical treatment facility may vary considerably. Tactical field care allows more time and a little more safety, to provide further medical care.

But Remember – effective hostile fire could resume at any time.

After completing the Hemorrhage Control portion of Tactical Field Care, you will shift your focus to the casualty's airway and respirations. This module will show you how to evaluate the casualty’s respirations and perform a surgical airway, and/or treat an open pneumothorax or tension pneumothorax.

Objectives

Videos

Guidelines and Key Points

Respiration/Breathing

- Assess for tension pneumothorax and treat as necessary.

- Suspect a tension pneumothorax and treat when a casualty has significant torso trauma or primary blast injury and one or more of the following:

⁃ Severe or progressive respiratory distress

⁃ Severe or progressive tachypnea

⁃ Absent or markedly decreased breath sounds on one side of the chest

⁃ Hemoglobin oxygen saturation < 90% on pulse oximetry

⁃ Shock

⁃ Traumatic cardiac arrest without obviously fatal wounds

Note:

* If not treated promptly, tension pneumothorax may progress from respiratory distress to shock and traumatic cardiac arrest.

- Initial treatment of suspected tension pneumothorax:

⁃ If the casualty has a chest seal in place, burp or remove the chest seal.

⁃ Establish pulse oximetry monitoring.

⁃ Place the casualty in the supine or recovery position unless he or she is conscious and needs to sit up to help keep the airway clear as a result of maxillofacial trauma.

⁃ Decompress the chest on the side of the injury with a 14-gauge or a 10-gauge, 3.25-inch needle/catheter unit.

⁃ If a casualty has significant torso trauma or primary blast injury and is in traumatic cardiac arrest (no pulse, no respirations, no response to painful stimuli, no other signs of life), decompress both sides of the chest before discontinuing treatment.

Notes:

- Either the 5th intercostal space (ICS) in the anterior axillary line (AAL) or the 2nd ICS in the mid-clavicular line (MCL) may be used for needle decompression (NDC.) If the anterior (MCL) site is used, do not insert the needle medial to the nipple line.

- The needle/catheter unit should be inserted at an angle perpendicular to the chest wall and just over the top of the lower rib at the insertion site. Insert the needle/catheter unit all the way to the hub and hold it in place for 5-10 seconds to allow decompression to occur.

- After the NDC has been performed, remove the needle and leave the catheter in place.

* The NDC should be considered successful if:

⁃ Respiratory distress improves, or

⁃ There is an obvious hissing sound as air escapes from the chest when NDC is performed (this may be difficult to appreciate in high-noise environments), or

⁃ Hemoglobin oxygen saturation increases to 90% or greater (note that this may take several minutes and may not happen at altitude), or

⁃ A casualty with no vital signs has return of consciousness and/or ` radial pulse.

* If the initial NDC fails to improve the casualty’s signs/symptoms from the suspected tension pneumothorax:

⁃ Perform a second NDC on the same side of the chest at whichever of the two recommended sites was not previously used. Use a new needle/catheter unit for the second attempt.

⁃ Consider, based on the mechanism of injury and physical findings, whether decompression of the opposite side of the chest may be needed.

* If the initial NDC was successful, but symptoms later recur:

⁃ Perform another NDC at the same site that was used previously. Use a new needle/catheter unit for the repeat NDC.

⁃ Continue to re-assess!

* If the second NDC is also not successful:

⁃ Continue on to the Circulation section of the TCCC Guidelines.

2. All open and/or sucking chest wounds should be treated by immediately applying a vented chest seal to cover the defect. If a vented chest seal is not available, use a non-vented chest seal. Monitor the casualty for the potential development of a subsequent tension pneumothorax. If the casualty develops increasing hypoxia, respiratory distress, or hypotension and a tension pneumothorax is suspected, treat by burping or removing the dressing or by needle decompression.

3. Initiate pulse oximetry. All individuals with moderate/severe TBI should be monitored with pulse oximetry. Readings may be misleading in the settings of shock or marked hypothermia.

4. Casualties with moderate/severe TBI should be given supplemental oxygen when available to maintain an oxygen saturation > 90%.

Tension pneumothorax is a very common cause of preventable death on the battlefield, yet it is easy to treat. It may occur with entry wounds in abdomen, shoulder, or neck. Blunt (motor vehicle accident) or penetrating trauma (such as a GSW) may also cause it.

If the casualty does not have a tension pneumothorax when you do your needle decompression, the needle won’t make it worse if there is no tension pneumothorax. If he DOES have a tension pneumothorax, you will save his life.

Tension pneumothorax is a common but easily treatable cause of preventable death on the battlefield. Diagnose and treat it aggressively! DO NOT MISS THIS INJURY!

Vented chest seals work reliably to prevent a tension pneumothorax in the presence of an open pneumothorax and an ongoing air leak from the lung, but non-vented chest seals do not.

Once the wound has been occluded with a dressing, air can no longer enter (or exit) the pleural space through the wound in the chest wall. The injured lung will remain partially collapsed, but the mechanics of respiration will be better. You have to be alert for the possible development of tension pneumothorax because air can still leak into the pleural space from the injured lung.

Summary

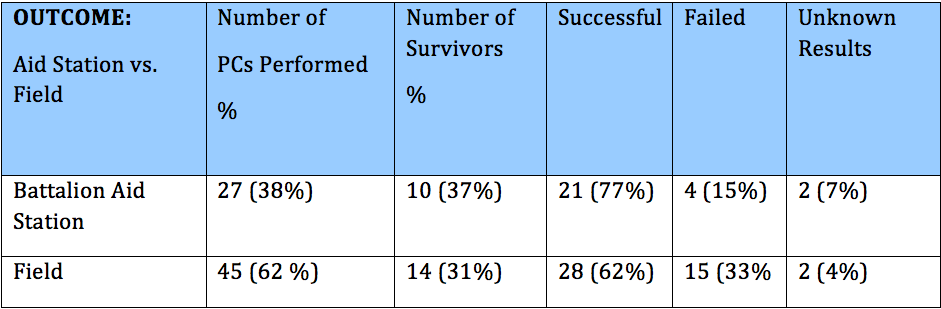

Analysis of Battlefield Cricothyrotomy in Iraq and Afghanistan

Robert L. Mary, MD; Alan Frankfurt, MD, The Journal of Special Operations Medicine, J Spec Oper Med. 2012 Spring;12(1):17-23.

Historical review of modern military conflicts suggests that airway compromise accounts for 1-2 % of total combat fatalities. This study examines the specific intervention of pre-hospital cricothyrotomy (PC) in the military setting using the largest studies of civilian medics performing PC as historical controls

The majority of patients who underwent PC died (66%). The largest group of survivors had gunshot wounds to the face and/or neck (38%) followed by explosion related injury to the face, neck and head (33%). Military medics have a 33% failure rate when performing this procedure compared to 15% for physicians and physician assistants. Minor complications occurred in 21 % of cases. The survival rate and complication rates are similar to previous civilian studies of medics performing PC. However, the failure rate for military medics is three to five times higher than comparable civilian studies.

Take Home Message:

A Comparison of Two Open Surgical Cricothyroidotomy Techniques by Military Medics Using a Cadaver Model

Robert L. Mabry, MD; Matthew C. Nichols, DO; Drew C. Shiner, MD; Scotty Bolleter, BS, EMT-P; Alan Frankfurt, MD

Annals of Emergency Medicine, Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Jan;63(1):1-5.

The CricKey is a novel surgical cricothyroidotomy device combining the functions of a tracheal hook, stylet, dilator, and bougie incorporated with a Melker airway cannula. This study compares surgical cricothyroidotomy with standard open surgical versus Cric Key technique

Participants included US Army combat medics credentialed at the emergency medical technician–basic level. After a brief anatomy review and demonstration, 15 military medics with minimal training performed in random order standard open surgical cricothyroidotomy and CricKey surgical cricothyroidotomy on cadavers. Compared with the standard open surgical cricothyroidotomy technique, military medics demonstrated faster insertion with the CricKey. First-pass success was notsignificantly different between the techniques.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message

Implications for Needle Thoracentesis in Tension Pneumothorax

Chest Wall Thickness in Military Personnel: Implications for Needle Thoracentesis in Tension Pneumothorax

COL H. Theodore Harcke, MC USA, COL H. Theodore Harcke, MC USA; LCDR Lisa A. Pearse, MC USN; COL Angela D. Levy, MC USA; John M. Getz, BS; CAPT Stephen R. Robinson, MC USN

Military Medicine, Vol. 172, December 2007

Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines and combat casualty care doctrine recommend the use of needle thoracentesis (needle thoracostomy) for the emergency treatment of tension pneumothorax. Emergency situations require a reproducible, simple, and effective response for treatment of life-threatening pneumothorax. This study evaluated chest wall thickness in a forward-deployed tri-service population using a retrospective analysis of multidetector CT (MDCT)-assisted autopsies performed on combat casualties at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

If needle thoracentesis is attempted with an angiocatheter or needle of insufficient length, the procedure will fail. Recommended procedures for needle thoracentesis to relieve tension pneumothorax should be adapted to reflect use of an angiocatheter or needle of sufficient length. A 3.25 inch angiocatheter would have reached the pleural space in 99% of the cases in this series.

READ FULL PDF