K9 Clinical Practice Guideline #14- Wound Management

K9 Combat Casualty Care Committee

Introduction

- These clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) apply to deployed human healthcare providers (HCPs) in combat or austere areas of operations. Veterinary care is established at multiple locations throughout theater, and the veterinary health care team is the MWD’s primary provider. However, HCPs are often the only medical personnel available to MWDs that are critically ill or injured. The reality is that HCPs will routinely manage working dogs in emergencies before they are ever seen by veterinary personnel.

- Care by HCPs is limited to circumstances in which the dog is too unstable to transport to supporting veterinary facilities or medical evacuation is not possible due to weather or mission constraints; immediate care is necessary to preserve life, limb, or eyesight; and veterinary personnel are not available. HCPs should only perform medical or surgical procedures – within the scope of their training or experience – necessary to manage problems that immediately threaten life, limb, or eyesight, and to prepare the dog for evacuation to definitive veterinary care. Routine medical, dental, or surgical care is not to be provided by HCPs.

- Emergent surgical management of injured MWDs may be necessary by HCPs to afford a chance at patient survival. This should be considered only if:

- The provider has the necessary advanced surgical training and experience.

- The provider feels there is a reasonable likelihood of success.

- The provider has the necessary support staff, facilities, and monitoring and intensive care facilities to manage the post-operative MWD without compromising human patient care.

- Emergent surgical management should be considered only in Role 2 or higher medical facilities and by trained surgical specialists with adequate staff. Direct communication with a US military veterinarian is essential before considering surgical management, and during and after surgery, to optimize outcome.

Open Wounds and Necrotic Tissue

MWDs with wounds are frequently presented for care. Wounds commonly result from ballistic injuries, bites, motor vehicle trauma, or other trauma. In most cases, traumatic wounds can be classified as contaminated or dirty/infected wounds; the difference is based on how long the wound existed before presentation. Contaminated wounds generally are considered those less than 6 hours old, and dirty/infected wounds are considered those greater than 6 hours old and generally with obvious exudates or infection. Wounds are often noted in conjunction with potentially life-threatening injuries; thus, in all MWDs presenting with wounds, a detailed systematic triage examination and a careful search for – and management of – more severe concurrent injuries must take precedent over management of wounds. In all instances, wound care follows resuscitation and stabilization of the patient.

Considerations in Wound Management

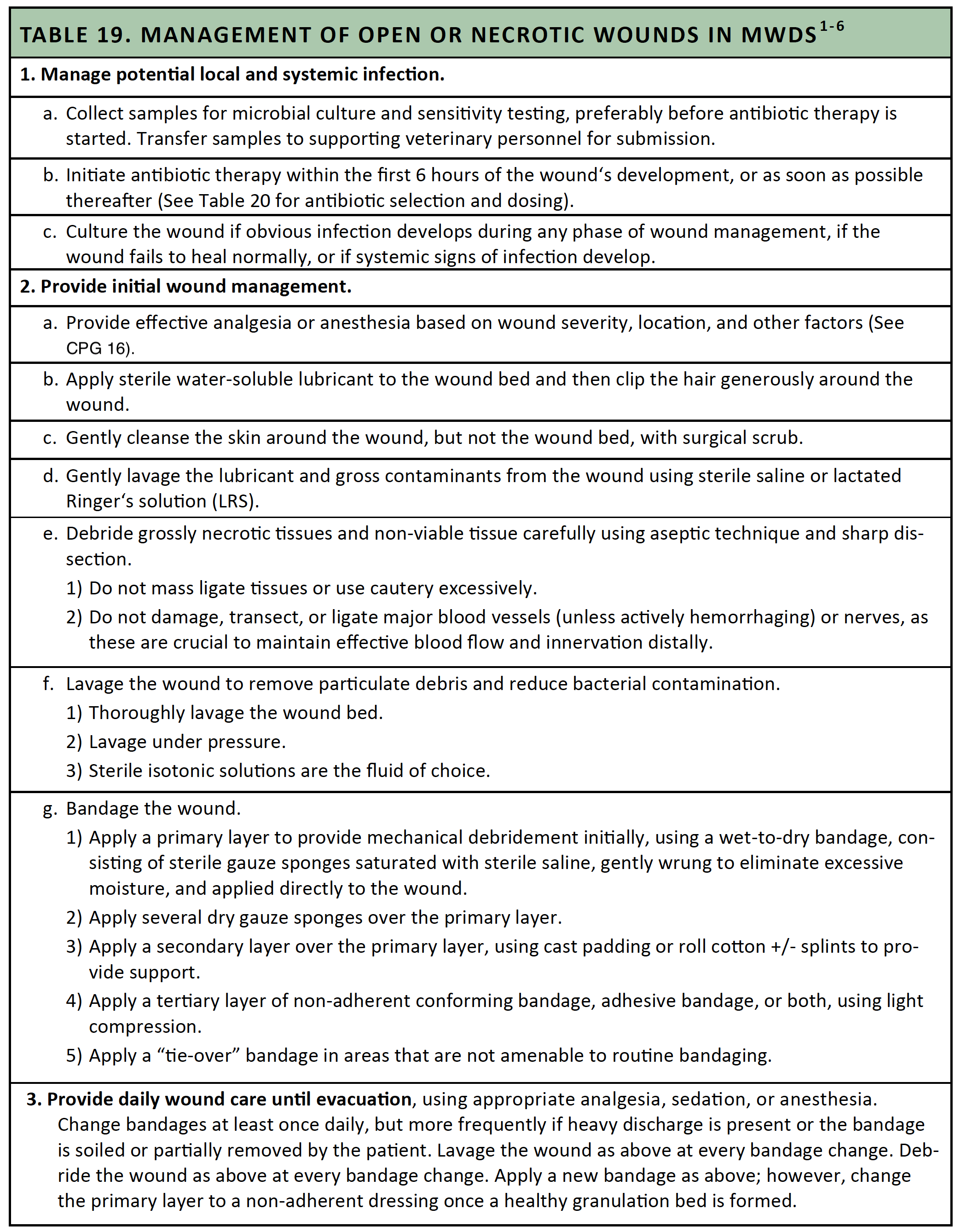

The primary goal in wound management is to create a healthy wound bed, one that has adequate blood supply to support repair, and without contamination or necrotic tissue that will impede healing and increase the risk of infection. Unless simple and small, many wounds will require frequent evaluation, generally at least once daily, based on location, extent, severity, and other factors. Many wounds will need to be managed as open wounds (although protected by bandages until smaller) before definitive surgical repair. The steps in daily wound evaluation are to assess the response to or need for antibiotics, debride dying or necrotic tissues and lavage the wound, assess for surgical closure, and protect the wound.

Initial Wound Management Recommendations

Provide effective analgesia or anesthesia based on wound severity, location, and other factors (See CPG 16 and Table 19).1-6

- Apply sterile water-soluble lubricant liberally to the wound bed and then clip the hair generously around the wound. Gently cleanse the skin around the wound, but not the wound bed, with surgical scrub. Gently lavage the lubricant and gross contaminants from the wound using sterile saline or lactated Ringer‘s solution (LRS); do not use tap water except in very grossly contaminated wounds with large amounts of debris, in which case it may be more expedient to flush the wound with warm water under gentle pressure initially. The goal of initial lavage is to remove gross contaminants and reduce the bacterial burden.

- Debride grossly necrotic tissues and non-viable tissue carefully using aseptic technique and sharp dissection. Do not mass ligate tissues or use cautery excessively, as this usually leads to necrosis of these tissues and serves as a bed for infection. Use caution not to damage, transect, or ligate major blood vessels (unless actively hemorrhaging) or nerves, as these are crucial to maintain effective blood flow and innervation distally.

- Lavage of the wound is necessary to remove particulate debris and reduce bacterial contamination – remember the adage, “The solution to pollution is dilution.”

- There are several devices acceptable and available for adjunctive wound irrigation. Simple bulb irrigation and gravity irrigation have been the preferred method of wound irrigation. The bulb and syringe method has been more widely accepted and is significantly less expensive. Large bore gravity-run tubing has been favored for quick irrigations. Pulsatile jet lavage irrigation using a battery powered system is another method of adjunctive irrigation in the overall management of contaminated crushed wounds. It must be emphasized that all methods of wound irrigation, including pulsatile lavage, are adjuncts to sharp, surgical debridement and not a substitute for surgical debridement.

- Normal saline, sterile water and potable tap water all have documented similar usefulness, efficacy and safety. Sterile isotonic solutions are readily available and remain the fluid of choice for irrigation. If unavailable, sterile water or potable tap water can be used.

- Bacterial loads drop logarithmically with increasing volumes of 1, 3, 6, and 9 liters of irrigation. The current recommendations are as follows: 1-3 liters for small volume wounds, 4-8 liters for moderate wounds, and 9 or more liters for large wounds or wounds with evidence of heavy contamination.3

- Generally, contaminated and dirty/infected wounds should not be sutured until healthy granulation tissue is established, which generally occurs in 3-5 days. This is especially true for bite wounds.

Table 19. Management of Open or Necrotic Wounds in MWDs

Bandaging Recommendations

- In nearly all cases, open wounds should be bandaged to protect the wound from contamination and support the wound while it heals. In most cases, mechanical debridement is desired (i.e., in most wounds after initial management has been performed, with varying degrees of contamination or infection), so use an adherent dressing. Once a healthy granulation bed has formed, convert to a non-adherent dressing.

- The most common adherent dressing is a wet-to-dry bandage, consisting of sterile gauze sponges that are saturated with sterile saline, gently wrung to eliminate excessive moisture, and the applied directly to the wound. Over the wet dressing, several dry gauze sponges are applied. In large wounds, laparotomy sponges may be optimal to cover more wound bed.

- The most common non-adherent dressing is a semi-occlusive cotton pad (e.g., Telfa®) that retains moisture against the wound bed and ‘wicks‘ exudate from the surface of the wound.

- Use topical silver sulfadiazine ointment or triple-antibiotic ointment on most wounds.

- Apply a secondary layer over the primary layer. Most commonly, rolled cast padding or roll cotton is used to provide support. Splints can be included in the secondary layer, if used.

- Apply a tertiary layer, typically consisting of non-adherent conforming bandage, adhesive bandage, or both. This layer holds the dressing and secondary layer in place, provides additional support, and provides more durable protection of the underlying layers. In most cases, the tertiary layer is applied just tight enough to hold the bandage in place, and without compression.

- Change bandages at least once daily. More frequent bandage changes may be necessary if the wound has a heavy discharge or the bandage becomes soiled or partially removed by the MWD. Once wound discharge is reduced and a healthy granulation bed has formed, bandage changes become less frequent, generally every 2-3 days.

- Any MWD with a bandage applied must be prevented from chewing at the bandage. A plastic bucket with the bottom cut out can be used to prevent self-trauma can be attached to the dog‘s collar as an effective prevention practice (See Figure 21 and Figure 22).

- Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT; e.g., WoundVac®) has proven a viable treatment modality for wounds in dogs, but requires proper training to apply properly to dogs and frequently heavy sedation of the MWD to prevent disruption of the dressing. HCPs with experience with NPWT are encouraged to consult with supporting veterinary personnel if this treatment modality is considered necessary before the MWD is evacuated to a veterinary facility. In most cases, application of NPWT can be delayed until the MWD is evacuated to a veterinary facility for long-term care.

- A “tie-over” bandage should be used in locations that are difficult to place a bandage, such as the inguinal area, dorsum, hip, and flank. Routine bandages placed in these areas typically slip off, and fail to protect the wound. A tie-over bandage consists of the same layers of bandage material, whether adherent or non-adherent, placed within and over the wound in a packing fashion. Multiple suture loops are placed around the periphery of the wound in the skin, evenly spaced around the wound, using large (2-0 or larger) monofilament suture material. The wound is then covered with a portion of impermeable drape or similar material. The bandage is then secured using umbilical tape or similar material laced through the suture loops (see Figure 44). Ties of surgical masks are a good substitute if umbilical tape is not available. The ties should be sufficiently tight to hold the bandage in place, with mild tension on the suture loops. The covering layer should be snug over the top of the underlying layers. A tie-over bandage will not have a compression layer.

Figure 44. Tie-Over Bandage

Antibiotic Use with Open or Necrotic Wounds

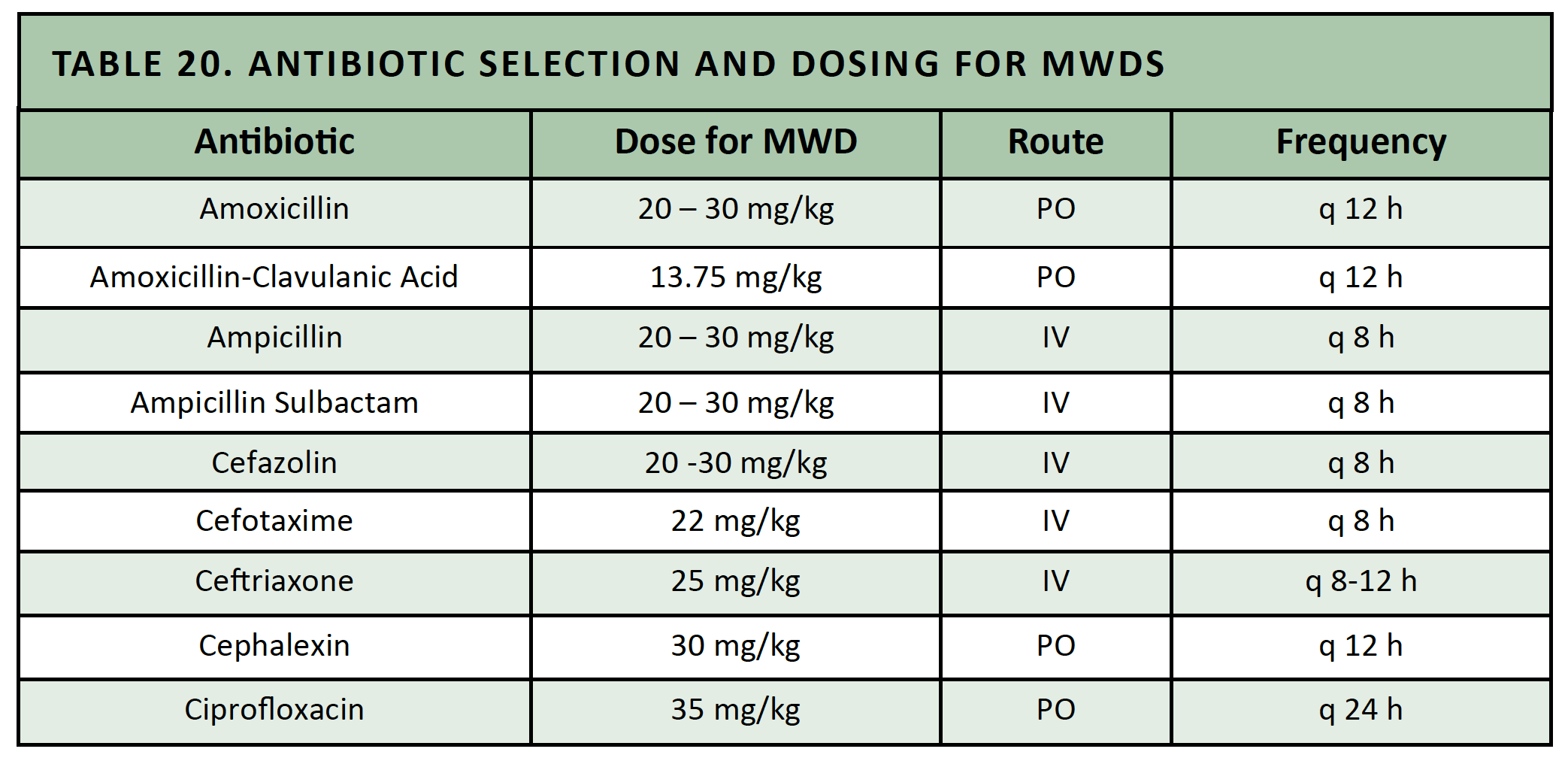

Systemic antibiotics are indicated for any MWD with moderate or severe wounds. Wound cultures are indicated at admission if the patient presents with a dirty/infected wound, if obvious infection develops during any phase of wound management, if the wound fails to heal normally, or if systemic signs of infection develop. Continue antibiotics for a minimum of 7 days (See Table 20).

Table 20. Antibiotic Selection and Dosing for MWDs

References

- Garzotto CK. Wound management. In: Silverstein DC and, Hopper K, eds. Small Animal Critical Care Medicine. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2015;734-743.

- Halling K. Wounds and open fractures. In: Mathews K, ed. Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care Manual. Guelph, Ontario, Canada: Lifelearn, Inc., 2006;702-708.

- Gall TT and Monnet E. Evaluation of fluid pressures of common wound-flushing techniques. Am J Vet Res 2010;71:1384-1386.

- Papich MG. Ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetics and oral absorption of generic ciprofloxacin tablets in dogs. Am J Vet Res 2012;73:1085-91.

- Balsa IM, Culp WT. Wound Care. In: Veterinary Clinics of North American: Small Animal Practice 2015;45:1049-65.

- Davidson JR. Current Concepts in Wound Management and Wound Healing Products. In: Veterinary Clinics of North American: Small Animal Practice 2015;45:537-64.