Genitourinary Injury Trauma Management

Joint Trauma System

SUMMARY OF CHANGES

- New contemporary data/statistics

- New Ureteral Trauma Section

- Updates to urologic trauma and renal trauma algorithms

- Images of ureteral trauma and external genitalia

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Between 2001 and 2013, U.S. Service Members (SMs) sustained 1,631 amputations and 1,462 genitourinary (GU) injuries; excluding female GU injuries and those who died from their wounds, there were 1,367 patients who made up 5.3% of all injuries sustained in Afghanistan and Iraq.1 The trend of GU injuries continued to rise, mostly secondary to an increased incidence of complex blast injuries (dismounted improvised explosive device injuries), to an annual incidence of over 13% before the Iraq drawdown in 2011, with an overall incidence of 7.2% between 2007 and 2020.2 The injury patterns varied, with 73% involving the external genitalia; injuries included scrotal (56%), testicular (31%), penile (21%), and renal (9.1%).1,3 GU injuries are often a component of more severe polytrauma, primarily caused by explosive mechanisms and require a high amount of resources. Comorbid injuries included traumatic brain injuries (40%), lower extremity amputations (29%), pelvic fractures (25%) and colorectal injuries (22%).1

Patients who sustained these injury patterns most often survived their injuries (94%), requiring numerous resources for short-term survival and long-term rehabilitation. The median injury severity scores for this population were 18 (IQR 10-29), with high associated injury severity scores to the abdomen/pelvis (2; 0-3) and extremities (3; 0-3).2 Massive transfusion protocols (MTP), defined as 10 or more units of blood given within 24 hours, were activated 4.4 times more in patients with complex blast injuries that included GU wounds (RR=5.08) from 2007 to 2020. Overall, 35% of all injuries with GU involvement required MTP. Of all MTPs during these 13 years, GU injuries made up 28%.2

Genitourinary surgery constitutes approximately 1.15% of procedures performed for combat injuries. During forward deployment, surgeons usually deploy without urology support.1 Mirroring the above injury patterns, the most common procedures involve testis (21%), bladder (19%), scrotum (18%), and kidneys (14%). The most common individual procedures performed were unilateral orchiectomy (394, 9.9%), suture of laceration of scrotum and tunica vaginalis (373, 9.4%), nephroureterectomy (360, 9.1%), and suprapubic cystostomy (268, 6.8%). Orchiectomies occurred 48% of the time for any testicular surgery, and nephroureterectomies occurred 67% of the time for any surgery to the kidneys.1,3,4 Surgery on the male genitalia, bladder, and kidney comprised the most commonly required genitourinary operative procedures at deployed facilities.1 All deploying surgeons may be required to evaluate, stage, and surgically manage genitourinary and gynecologic conditions. Therefore, all surgeons should be familiar with the appropriate treatment of these injuries.

These guidelines provide direction for the identification of life-threatening GU injuries, control of hemorrhage, the establishment of urinary drainage, and the preservation of GU function when possible.

BACKGROUND

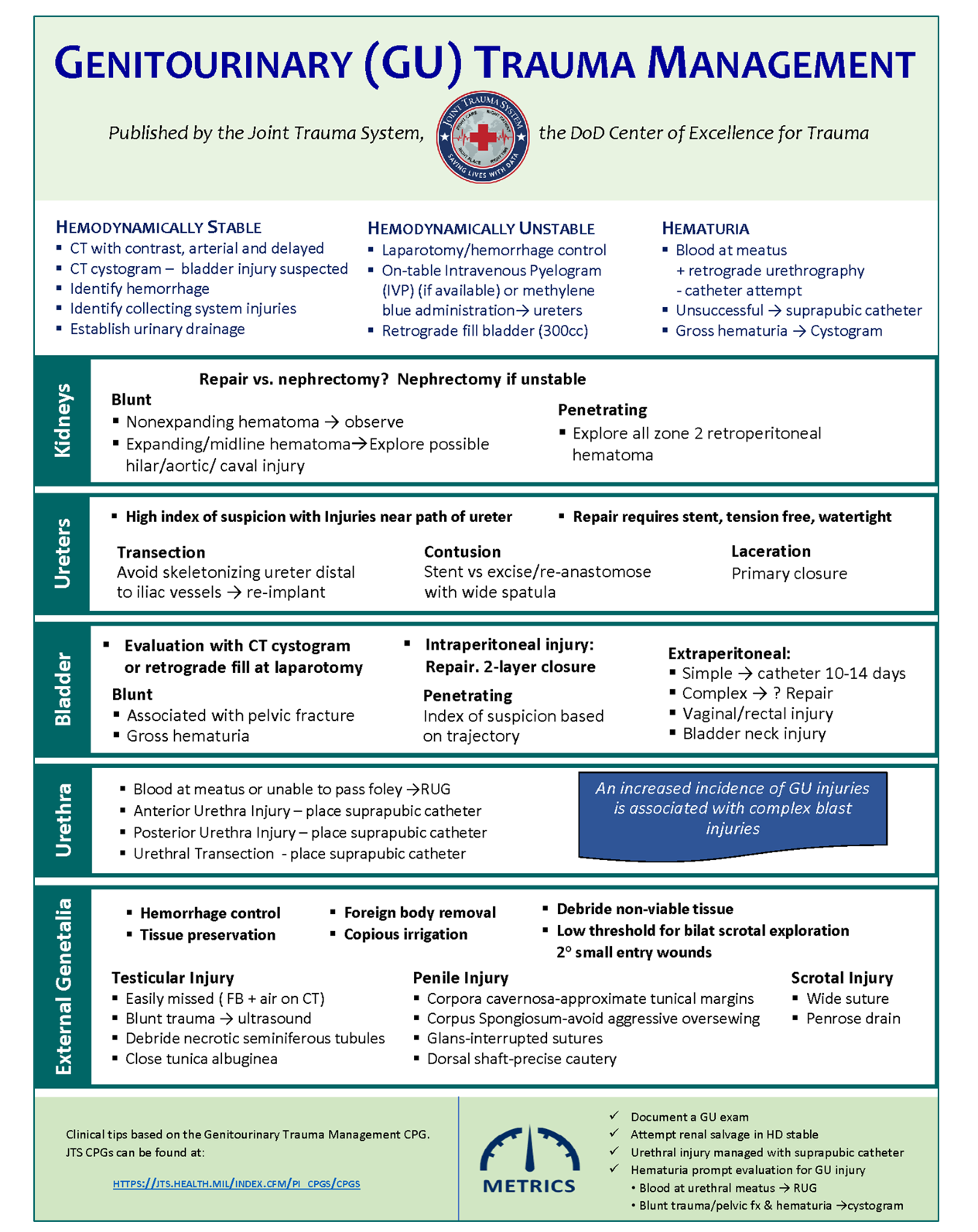

Management of GU injuries requires a systematic approach to imaging and treatment that adheres to established surgical and trauma principles. Establishing the patient's hemodynamic stability is critical to the initial evaluation. Stable patients are afforded a rigorous radiographic evaluation that identifies genitourinary sites of injury and allows for the safe establishment of urinary drainage. Recognizing that intra-abdominal GU injuries are often associated with significant vascular and visceral injuries is essential to determining management priorities. Unstable patients, on the other hand, require rapid surgical evaluation and hemorrhage control.4 Preservation of as much tissue as possible, particularly when dealing with the external genitalia, should be an additional goal for far-forward surgeons. Current combat casualty care principles allow for multiple surgical evaluations along the path of evacuation to tertiary centers outside the theater of operations, where tissue re-evaluation, wound irrigation, further debridement, and definitive treatment can occur.5

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Ten percent of all combat casualties in current U.S. conflicts have GU injuries, which may be blunt, penetrating, or combined. The extensive use of improvised explosive devices (IED) resulted in a substantial number of penetrating injuries that include GU organs as part of a complex wounding pattern with trauma to the abdomen, pelvis, perineum, and extremities.5-11 A significant reduction in kidney injuries has been noted in combat casualties wearing body armor.12 Given the mechanism of injury, the most commonly injured GU structures are the external genitalia and lower urinary tract (bladder and urethra).8,13,14 Because most patients with GU injuries are severely injured, as mentioned above, a thorough initial trauma evaluation and treatment following proper Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) and Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) and damage control resuscitation principles is critical.

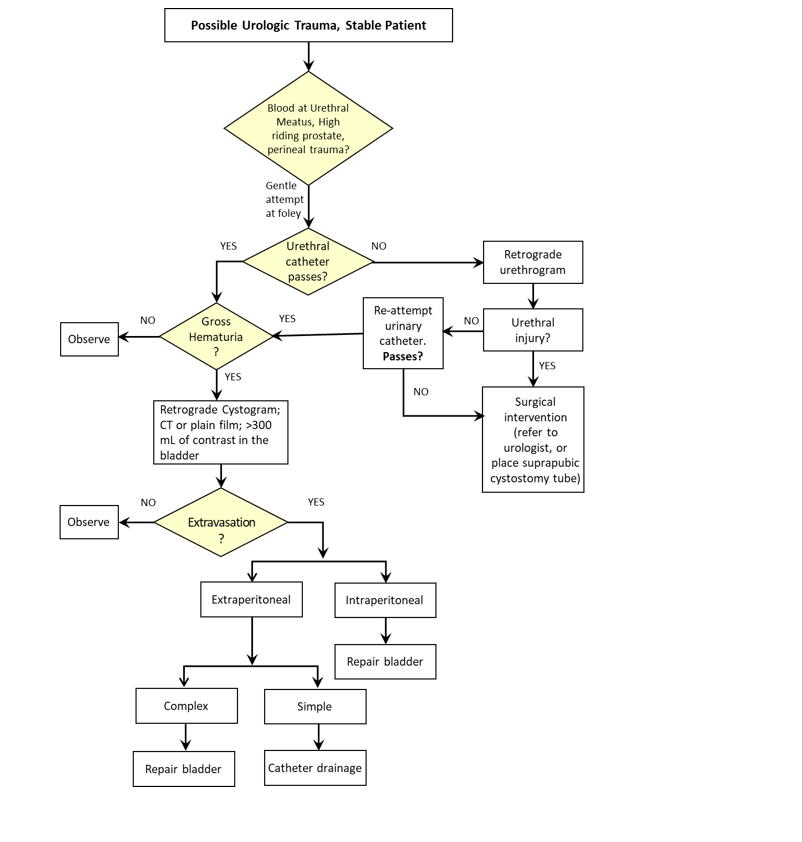

Severely injured patients typically warrant bladder drainage via catheter placement to facilitate urinary drainage and assist with hemodynamic monitoring via hourly assessment of urine output (Figure 1). A urethral injury should be suspected in the setting of blood at the urethral meatus or a high-riding prostate on the initial rectal exam. In these situations, or if there is any difficulty with initial catheter placement, urethral integrity must be evaluated via retrograde urethrography. 6, 15 The inability to safely pass a catheter should prompt suprapubic catheter placement.

- A urinalysis should be obtained after successful catheter placement, and any gross hematuria should be immediately noted. Evaluation for renal or bladder injury is necessary for patients with:

- Gross hematuria

- Microscopic hematuria AND an initial systolic BP < 90 mmHg (after they become hemodynamically stable)

A mechanism of injury or physical examination findings suggestive of renal injury (i.e. rapid deceleration, rib fracture(s), flank ecchymosis, pelvic fracture, or a penetrating injury to the abdomen, flank, or lower chest).15

The patient's hemodynamic stability, the operational environment, and the capabilities of the medical treatment facility will dictate which radiographic and surgical evaluation resources are available at each echelon of care. The preferred imaging test to evaluate renal and ureteral injury is an intravenous (IV) contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) with arterial and delayed phase imaging.15 During the initial evaluation of patients with hematuria, it is essential to note that the severity of hematuria (gross or microscopic) does not necessarily correlate to the severity of the injury.14 For example, it is possible to have minimal hematuria despite high-grade renal damage such as disruption of the ureteropelvic junction, pedicle injuries, and segmental arterial thrombosis.13 Conversely, low-grade renal injury can result in ongoing gross hematuria. Thus, proper injury staging, and a high index of suspicion are critical regardless of hematuria severity. In cases of blunt renal trauma, most injuries can be managed conservatively. The grading scale is listed in the Renal Injury table section in Appendix A: Urological Diagnosis and Treatments.

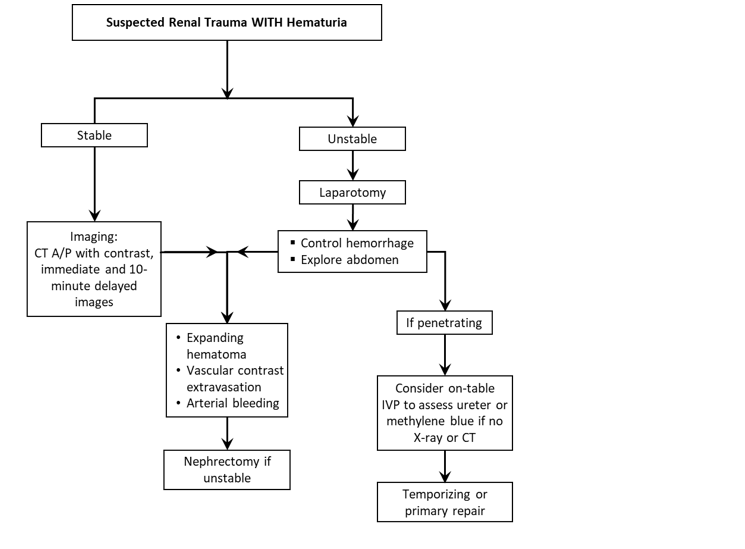

RENAL TRAUMA

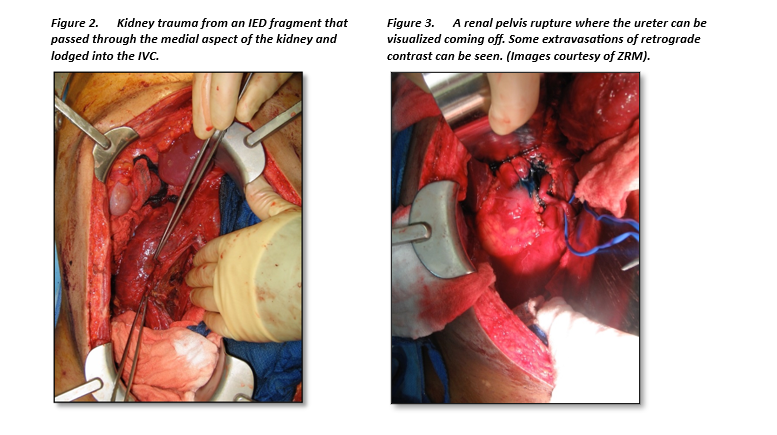

Patients with penetrating renal injuries often have associated injuries to other intra-abdominal organs that require laparotomy. All Zone 2 (perinephric) penetrating wounds should be explored following principles of vascular injury repair in the retroperitoneum after ensuring methods for proximal and distal vascular control. Generally, in the case of blunt injury, a hematoma confined to the retroperitoneum can be left undisturbed; however, persistent bleeding, expanding hematoma, or medial hematomas suggest a hilar, aortic, or caval injury and warrant direct evaluation (Figure 2 & 3).6

The decision to repair or remove the damaged kidney at that time depends on the kidney's salvageability, the patient's ability to tolerate the procedure, and the availability of resources. Kidney preservation should only be considered if the patient is hemodynamically stable, the surgeon has experience with renorrhaphy, and has considered this after discussion with a urologist. Renal preservation strategies include conservative management, selective angioembolization, and renorrhaphy. The necessary resources and expertise for embolization or renorrhaphy may not be available in theater. Additionally, the risks of renorrhaphy (delayed bleed and/or urine leak) should be considered in determining the best management for the patient. Several studies raised concern that nephrectomy may be associated with increased mortality. However, these studies were not able to account for transfusion requirements.16,17 A more recent study which was able to control for the degree of transfusion concluded nephrectomy itself was not associated with mortality, and instead, shock is the driver of mortality in high-grade renal trauma.18 Although kidney preservation should be the goal in appropriate patients, surgeons should not hesitate to perform nephrectomy in unstable patients with high-grade renal trauma or when the necessary resources are unavailable for angioembolization or renorrhaphy. The presence of a contralateral kidney should be determined before nephrectomy by palpation or on-table imaging (e.g., one-shot IVP: 2 mL/kg IV bolus of contrast followed by a single abdominal radiograph 10-15 minutes later). High-velocity kidney injuries are difficult to reconstruct and often require nephrectomy. (See Nephrectomy Section in Appendix A: Urological Diagnosis and Treatments.) 19

An algorithmic approach to renal trauma management is presented in Figure 4 below.

BLADDER TRAUMA

Bladder injuries may be secondary to blunt or penetrating trauma. Bladder rupture from blunt trauma is typically associated with pelvic fracture and gross hematuria. Thus, combining these two findings (hematuria + pelvic fracture) warrants retrograde plain film or CT cystography to evaluate for bladder injury.15 The bladder must be filled with at least 300cc of contrast and images with the bladder distended and the bladder emptied of contrast must be obtained to fully evaluate for contrast extravasation or intramural hematoma. Some of these bladder injuries may be small and additional views or further image reconstruction may be required in order to fully evaluate. Penetrating bladder injury must be excluded when the trajectory of the penetrating object is near the pelvis or lower abdomen.20 If possible, retrograde (plain film or CT) cystography should be performed before exploratory laparotomy. However, when imaging is not possible before abdominal exploration, large intraperitoneal bladder injuries can be rapidly excluded by filling the bladder in a retrograde fashion until distended (300 mL is usually sufficient in most patients) with sterile saline or dilute methylene blue via the Foley catheter and inspecting for leakage of the fluid into the peritoneal cavity. Unfortunately, extraperitoneal injuries cannot be reliably excluded using this technique.

While intraperitoneal bladder rupture must be repaired, most simple extraperitoneal injuries can be managed non-operatively with Foley catheter drainage for 10-14 days, depending on the extent of the damage (Figure 5). Conversely, complex extraperitoneal injuries will benefit from immediate repair. Examples of complex extraperitoneal bladder injury include pelvic fractures with bone fragments in the bladder lumen, concurrent rectal or vaginal lacerations, bladder neck injuries, severe gross hematuria with clot obstruction of the catheter, and when the patient is undergoing open repair of concurrent abdominal pelvic injuries in the stable patient.15 Bladder repair is performed using a two-layer closure with absorbable sutures and at least 2 weeks of bladder catheter drainage. It is safe to place a drain adjacent to a bladder repair, as long as the drain is in a dependent position and not immediately abutting the suture line. If the patient has concomitant injuries requiring bowel resection and anastomoses, care must be taken to avoid placing these in close proximity to the bladder repair. Fluid can be sent from the drain postoperatively to measure creatinine levels and assess for bladder leak. (See Bladder Injuries in Appendix A: Urological Diagnosis and Treatments.) It is important to note that bladder injury from penetrating trauma has a high incidence of concurrent rectal injury,23 and a rectal exam and proctoscopy are indicated.

URETERAL TRAUMA

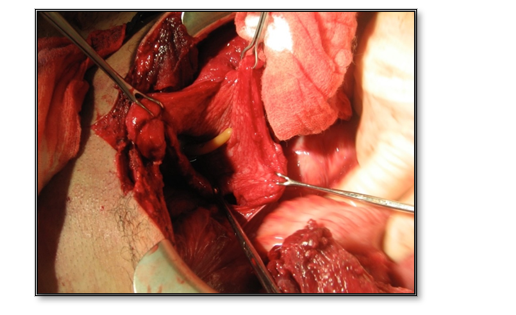

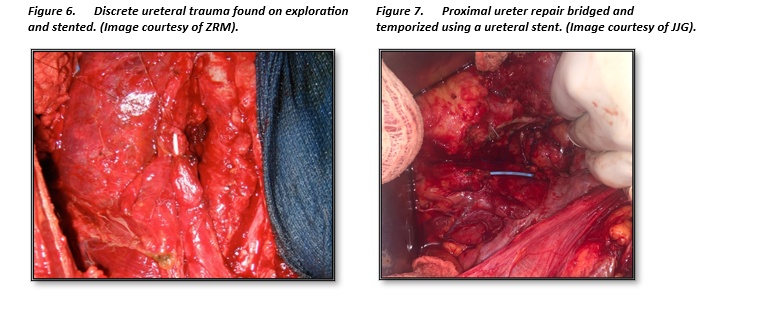

Ureteral injuries are nearly always secondary to penetrating trauma. A high index of suspicion based upon suspected bullet or fragment trajectory is necessary to avoid missing injuries; careful exploration of the ureter is needed in this setting (Figure 6).21,22 Gross hematuria may be absent, and the only clue may be injuries to organs close to the path of the ureter or an unexplained rise in serum creatinine. Injuries may be primarily repaired if ureteral damage is identified during initial exploration. Care should be taken not to skeletonize the ureter during exploration, and if a stented, tension-free, and watertight anastomosis or reimplant is not possible, the ureter should be 'tagged' for later repair and widely drained at a minimum. If primary repair is not an option, extracorporeal drainage with a small feeding tube, stent, or percutaneous nephrostomy tube (if available in theater) should be initiated as a temporizing treatment until the patient is stable and can be evaluated at a tertiary care facility (Figure 7).21

Ureteral contusions require stenting or excision and primary anastomosis with wide spatulation of the injured portion. Simple lacerations need a primary closure, while complete transections of the ureter proximal to the iliac vessels can be repaired using a tension-free end-to-end, spatulated anastomosis over a stent placed in the ureter. Transections distal to the vessels should be fixed with ureteral reimplantation over a stent. In some circumstances, a psoas hitch or Boari flap may be required for additional length. Again, if local tissue destruction prevents the ability to create a tension-free anastomosis, or there is the presence of hemodynamic instability dictating management, a pediatric feeding tube or open-ended ureteral catheter may be placed in the proximal ureter and traversed through the skin to close drainage alternatively. Interim temporizing repair techniques pending an evacuation to a tertiary care center are often appropriate.1,21 (See Appendix A: Urological Diagnosis and Treatments.)

EXTERNAL GENITALIA

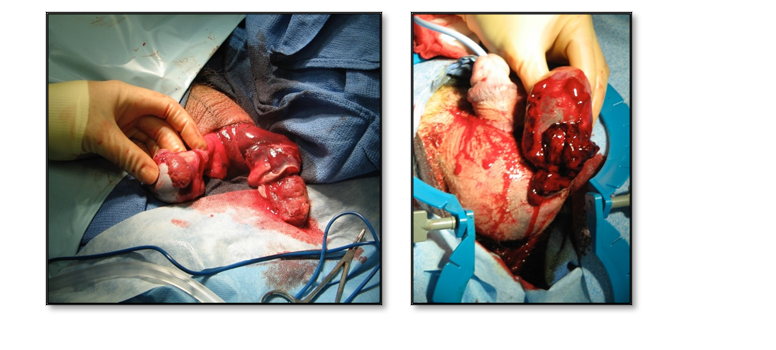

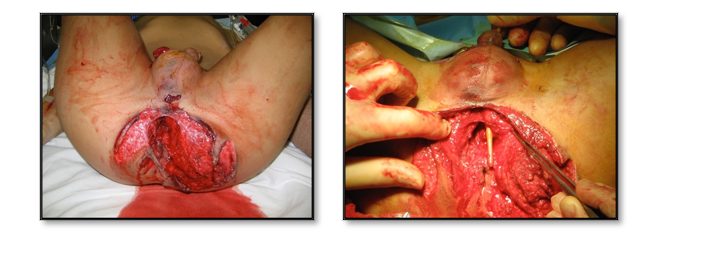

With the rise in dismounted complex battle injuries from explosive devices during combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and polytrauma involvement of the lower extremities, perineum, pelvis, and lower abdomen, greater attention has turned to the management of soft tissue injury to the external genitalia and urethra. Testicular injuries are easily missed due to small scrotal entry wounds in some cases and require a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with significant blast injuries. If you are suspicious of penetrating trauma or believe it may be possible, a low threshold should be employed to explore the scrotum bilaterally. This holds true for blast injuries, as overpressure can cause testicular rupture in patients with no overt injury; a low threshold should be employed in these patients. (See Figure 8).

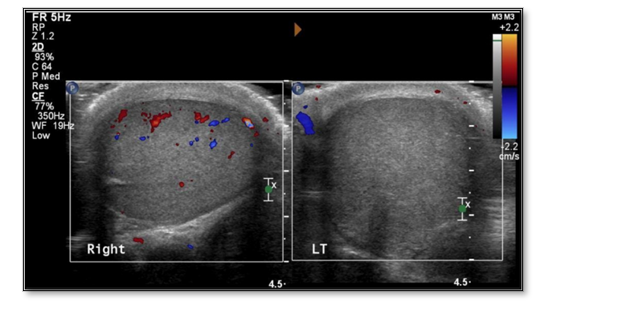

For blunt trauma, and in the hands of an experienced physician, bedside ultrasonography can be considered; vascular flow settings can be used to identify testicular rupture and compromised vascular flow (Figure 9).24 Clinicians should not rely on ultrasound for penetrating trauma; most penetrating scrotal injuries should be explored due to the limited sensitivity and variable levels of skill with ultrasound.15

Initial operative management involves thoroughly assessing the injury sites, removing wound contaminants, and debriding non-viable tissue. This is done in conjunction with copious, low-pressure irrigation of the wound.7 (See External Genitalia Injuries in Appendix A: Urological Diagnosis and Treatments.)

In addition to arterial bleeding, vascular structures of the penis and scrotum should be addressed during the initial surgery, specifically, the corpora cavernosa, corpus spongiosum, and bilateral testes (Figure 10). Lacerations to the corpora cavernosa can be closed with absorbable sutures. Attempts should be made to avoid the dorsal neurovascular structures. If the injury is dorsal, the neurovascular structures can be elevated off the corpora cavernosum to preserve the vascular supply to the glans and sensation to the penis. Avoid aggressive over-sewing of the corpus spongiosum in favor of closure to its tunical covering reducing the risk of ischemic changes distal to the injury site in these complex wounds.24,25 Patients with penetrating scrotal wounds or evidence of testicular rupture on exam should undergo scrotal exploration. Ruptured testes are managed with irrigation and debridement of non-viable seminiferous tubules. The tunica albuginea is then closed with fine (4-0 or 5-0) absorbable suture (PDS or Vicryl), returned to the scrotum, and an orchiopexy with three-point fixation is performed.15 A tunica vaginalis flap can be used to close the defect when there is insufficient tunica to obtain a tension-free closure over the exposed tubules. A drain (e.g., Penrose) should typically be left following scrotal exploration for trauma.26 A delay in managing a testicular injury is acceptable when the patient is too unstable or there is insufficient expertise to manage it at initial exploration. Every attempt should be made to salvage viable testicular tissue, especially when both testicles are involved or a unilateral orchiectomy is required. The injured testis should be wrapped in saline-soaked gauze and protected with multiple layers of additional dressing. All findings should be documented and communicated to the next echelon of care.

The superficial fascia and skin layers of the penis can and should be left open following high-energy trauma. A loose approximation of these layers with interrupted sutures allows continued tissue evaluation and additional wound debridement. Therefore, a moist gauze or negative pressure dressing is appropriate. Alternatively, Penrose drains can be placed between loosely approximated interrupted sutures. In cases where scrotal closure is impossible, the testis can be covered with a non-adherent dressing followed by a negative pressure dressing. Creating a sub-dermal thigh pouch is rarely necessary during early surgical care.

With the recent introduction of female combatants to all roles in the military, GU injuries in female patients have risen. Of the nearly 1,500 service members in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom between 2001 and 2013, 1.3% were female. Injuries described in female service members thus far include bladder injury, vulvar injury, vaginal injury, and bladder and perineal injury. Currently, there is a limited evidence-based direction in managing these injuries. Initial care should focus on good exposure of the injured tissue with a complete examination to include the vaginal vault, urethra, and meatus with low-pressure irrigation and judicious debridement of devascularized tissue. Limited debridement should be practiced around the clitoris, favoring repeat examinations in the operating room with intervention as needed. This new injury pattern is being prospectively tracked to ensure the best appropriate care.28,29

URETHRAL TRAUMA

Urethral injuries are identified by retrograde urethrography. However, some surgical teams may not have the contrast or X-ray capability to perform retrograde urethrography, such as far-forward austere resuscitative surgical teams or aircraft carrier surgical teams. If there is a concern for a urethral injury based on the injury mechanism, an attempt may be made to place a urinary catheter safely. The most experienced provider should perform this. A suprapubic catheter should be placed if any resistance or difficulty is encountered. Alternatively, a suprapubic catheter should be placed if there is blood at the meatus or concern for urethral injury based on mechanism. Complete transections of the urethra warrant suprapubic urinary drainage (See Algorithm for Urologic Trauma.)27

Blunt anterior urethral injuries should be diverted with a suprapubic cystostomy. This injury can be stented with a urethral catheter if an experienced surgeon is present. Posterior urethral injuries can be managed with suprapubic cystostomy alone.13 For complete urethral transections, suprapubic cystotomy is recommended (Figure 11).27 Penetrating anterior urethral injuries can be primarily repaired with a fine absorbable suture over a urethral catheter when the degree of soft tissue injury/contamination is limited. However, when complex blast injury results in anterior urethral injury associated with significant soft tissue loss of the perineum or genitalia, urinary diversion alone (transurethral or suprapubic) is sufficient to facilitate urinary drainage until the patient can be evaluated by a urologist who can assist with the wound care and complex urethrogenital reconstruction frequently needed in these cases. This is most appropriately performed at a Role 4 facility following multidisciplinary planning.

AEROMEDICAL EVACUATION CONSIDERATIONS

As for all postoperative and litter-bound patients, deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis should be initiated within 24 hours of injury if the patient has no signs/symptoms of ongoing hemorrhage (e.g., normal vitals, serial Hgb stable for 3 lab draws).See the JTS Prevention of Deep Venous Thrombosis – Inferior Vena Cava Filter CPG.

- Vibration and increased tissue edema in flight will increase pain. Ensure adequate en-route pain control by ordering breakthrough pain medications.

- Do not remove drains within 12 hours before movement.

- Avoid filling Foley Catheter balloon with air so the balloon does not expand in flight.

- Ensure foley is well-secured to the leg and that the bag is to gravity and visible for monitoring.

PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT (PI) MONITORING

- All patients with GU injury (kidney, ureter, bladder, testicles/ovaries, penis, external genitalia)

- All trauma patients with hematuria.

- All patients in the population of interest have a documented GU exam (e.g., presence/absence of blood in urethral meatus, ecchymosis/bruising in perineum, high-riding prostate).

- Patients with renal trauma undergo attempted renal salvage unless hemodynamically unstable.

- Patients with hematuria are evaluated for GU injury (if stable, obtain imaging when available, surgical exploration if unstable).

- When available, patients with blunt trauma, pelvic fracture, and hematuria are evaluated for bladder injury with cystography.

- Patients with suspected urethral injury or blood at the meatus undergo retrograde urethrography.

- A suprapubic catheter is placed for patients with identified urethral injury on retrograde urethrography or suspected urethral injury when urethrography is not available.

- Number and percentage of patients in the population of interest with documented GU exam.

- Number and percentage of patients undergoing nephrectomy at Role 2 or Role 3.

- Number and percentage of trauma patients with hematuria evaluated for GU injury (if stable, obtain imaging when available, surgical exploration if unstable).

- Number and percentage of patients with blunt trauma, pelvic fracture, and hematuria evaluated for bladder injury with cystography.

- Number and percentage of patients with suspected urethral injury or blood at the meatus who undergo retrograde urethrography.

- Number and percentage of patients with suprapubic catheter placement for suspected or identified urethral injury.

- Patient Record

- Department of Defense Trauma Registry (DoDTR)

The above constitutes the minimum criteria for PI monitoring of this CPG. System reporting will be performed annually; additional PI monitoring and system reporting may be performed as needed.

The JTS Chief and the JTS PI Branch will perform the systems review and data analysis.

The trauma team leader is responsible for ensuring familiarity, appropriate compliance, and PI monitoring at the local level with this CPG.

REFERENCES

- Kronstedt S, Boyle J, Fisher AD, et al. Male genitourinary injuries in combat–a review of United States and British forces in Afghanistan and Iraq: 2001-2013. Urology. 2022

- Kronstedt S, Boyle J, Fisher AD, et al. A contemporary analysis of combat-related urological injuries: data from the Department of Defense Joint Trauma System Data Registry. The Journal of Urology (2023): 10-1097.

- Turner CA, Orman JA, Stockinger ZT, Hudak SJ. Genitourinary surgical workload at deployed US facilities in Iraq and Afghanistan, 2002–2016. Military Medicine, Volume 184, Issue 1-2, 01 Jan 2019, e179–e185

- Banti M1, Walter J, Hudak S, Soderdahl D. Improvised explosive device-related lower genitourinary trauma in current overseas combat operations. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016 Jan;80(1):131-4.

- Dismounted Complex Blast Injury Task Force, Dismounted Complex Blast Injury Report of the Army, 18 Jun 2011.

- The Office of The Surgeon General, Borden Institute. Emergency War Surgery, 5th US Edition, 2018. Chap18-19:275-311.

- Joint Trauma System, War wounds: wound debridement and irrigation CPG, 27 Sep 2021.

- Serkin F, Soderdahl D, Hernandez J, et al. Combat urologic trauma in US military overseas contingency operations. J Trauma 69: S175-178, 2010.

- Thompson I, Flaherty S, Morey A. Battlefield urologic injuries: the Gulf War experience. J Am Coll Surg. 1998.187:139-141.

- Hudak S, Hakim S. Operative management of wartime genitourinary injuries at Balad Air Force Theater Hospital, 2005 to 2008. J Urol. 2009.182: 180-183.

- Hudak S, Morey A, Rozanski T, Fox C. Battlefield urogenital injuries: changing patterns during the past century. Urology 2005.65: 1041-1046.

- Paquette E. Genitourinary trauma at a combat support hospital during Operation Iraqi Freedom: the impact of body armor, J Urol. 2007.177: 2196-2199.

- Banti M, Walter J, Hudak S, Soderdahl D. Improvised explosive device-related lower genitourinary trauma in current overseas combat operations. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016 Jan;80(1):131-4

- Waxman S, Beekley A, Morey A, Soderdahl D. Penetrating trauma to the external genitalia in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Int J Impot Res. 2009 Mar-Apr;21(2):145-8.

- Morey AF, Brandes S, Dugi DD 3rd, et al. Urotrauma: AUA guideline. American Urological Association. J Urol. 2014 Aug;192(2):327-35.

- Anderson RE, Keihani S, Das R, et al. Nephrectomy is associated with increased mortality after renal trauma: an analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank from 2007-2016. J Urol. 205:841-7. 2021.

- Heiner SM, Keihani S, McCormick BJ, et al. Nephrectomy after high-grade renal trauma is associated with higher mortality: results from the Multi-Institutional Genitourinary Trauma Study (MiGUTS). Urology. 157:246-52. 2021.

- McCormick BJ, Horns JJ, Das R, et al. Nephrectomy is not associated with increased risk of mortality of acute kidney injury after high-grade renal trauma: a propensity score analysis of the Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP). J Urol. 207: 400-406. 2022.

- Serafetinides E, Kitrey ND, Djakovic N, et al. Review of the current management of upper urinary tract injuries by the EAU Trauma Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol. 2015 May 67(5), 930–936.

- Azimuddin K, Ivatury R, Allman PJ, Denton DB. Damage control in a trauma patient with ureteric injury. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, Dec 1997, Vol 43 (6), p 977-979

- Kunkle D, B Kansas, Pathak A, Goldberg A, Mydlo J. Delayed diagnosis of traumatic ureteral injuries. J Urol. 176: 2503-2507, 2006.

- Elliott SP, McAninch JW. Ureteral injuries from external violence: the 25-year experience at San Francisco General Hospital. J Urol. 2003 Oct;170 (4 Pt 1):1213-6.

- Cinman NM , McAninch JW, Porten SP, et al. Gunshot wounds to the lower urinary tract: a single-institution experience. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Mar;74(3):725-30.

- Holliday TL, Robinson KS, Nicole D. Testicular rupture: a tough nut to crack. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2017 Aug; 1(3): 221–224.

- S Phonsombat, V Master, J McAninch. Penetrating external genital trauma: A 30-year single institution experience, J Urol. 180: 192-196, 2008.

- Williams M, Jezior J. Management of combat-related urological trauma in the modern era. Nat Rev Urol. 2013 Sep;10(9):504-12.

- McCormick, BJ, Keihani S, Hagedorn J, et al. A multicenter prospective cohort study of endoscopic urethral realignment versus suprapubic cystostomy after complete pelvic fracture urethral injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg 2023.94.2: 344-349.

- Reed AM, Janak JC, Orman JA, Hudak SJ. Genitourinary injuries among female US service members during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom: Findings from the Trauma Outcomes and Urogenital Health Project.

- Ferguson GG, Brandes SB. Gunshot wound injury of the testis: the use of tunica vaginalis and polytetrafluoroethylene grafts for reconstruction. J Urol. 2007 Dec;178(6):2462-5.

APPENDIX A: UROLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENTS

Treatment:

- Place a Foley catheter during trauma assessment unless contraindicated, such as blood at the urethral meatus or other evidence of urethral injury (pelvic fracture).

- Perform a retrograde urethrogram (RUG) before attempted catheterization when there is a concern for a urethral injury.

- RUG – Obtain an oblique plain film of the pelvis with the patient's bottom leg flexed at the knee and hip with the top leg straight. Severely injured patients or those with suspected spine fractures can be left supine. Alternatively, C-arm or fluoroscopy can be used. A 12 Fr Foley catheter or catheter-tipped syringe is inserted into the fossa navicularis; the penis is placed on traction, and 20 mL of undiluted water-soluble contrast is injected under gentle pressure. Images are obtained. The study is considered normal only if contrast enters the bladder without extravasation.

- For an anterior urethral injury, plan on repair in the operating room (OR). For a posterior urethral injury, a suprapubic catheter can be placed in the OR or percutaneously in the emergency department (ED) for patients who do not need surgery, and an appropriate kit is available. For partial urethral disruption by RUG, a single attempt with a well-lubricated catheter may be attempted by an experienced team member in the ED.

- If the catheter passes and gross hematuria is noted, proceed with GU diagnostic evaluation for bladder injury or a renal/ureteral source. C. scan with delayed images and CT cystogram are appropriate imaging studies (see technique description following).

Treatment:

- Clinicians should perform diagnostic imaging with intravenous (IV) contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) with delayed imaging in stable blunt trauma patients with gross hematuria or microscopic hematuria and systolic blood pressure < 90mmHG or in any stable trauma patients with the mechanism of injury or physical exam findings concerning for renal injury (e.g., rapid deceleration, significant blow to flank, rib fracture, significant flank ecchymosis, penetrating injury of abdomen, flank, or lower chest).

- Renal Injury Grading

- Grade 1: Sub-capsular hematoma

- Grade 2: Small parenchymal laceration (<1cm in depth)

- Grade 3: Deeper parenchymal laceration without entry into the collecting system

- Grade 4: Laceration into collecting system with extravasation; vascular injury with contained hemorrhage

- Grade 5: Shattered kidney or renal pedicle avulsion

- Hemodynamically stable patients can be managed without surgical exploration in most cases.

- Hemodynamically unstable patients with no or transient response to resuscitation should have an immediate intervention.

- Vascular repair is indicated for salvageable kidneys with renal artery or vein injury.

- Ureteral stenting may be needed for enlarging urinoma or persistent urinary extravasation with fever, pain, ileus, fistula, or infection.

Treatment:

- Stable perirenal hematomas found during exploration should not be routinely opened.

- Penetrating injuries to retroperitoneal zone 2 should be explored.

- Renal exploration should be performed at the time of laparotomy for persistent bleeding, expanding hematoma, or a central hematoma suggesting a renal hilum injury.

Treatment:

- Total nephrectomy is immediately indicated in extensive renal injuries when the patient's life is threatened by attempted renal repair.

- A common surgical approach is a lateral to medial mobilization of the kidney to expose the renal pedicle after incision of the peritoneal attachments of the colon to the lateral wall. While there is insufficient data to recommend initial vascular control of the renal pedicle through a mesentery window before exploration, this remains an acceptable principle for isolated renal surgery.

- Damage control by packing the wound to control bleeding and attempting to correct metabolic and coagulation abnormalities, with a plan to return for corrective surgery within 24 hours is an option.

Treatment:

- Non-surgical management can result in renal preservation even with high-grade injuries. Renal repair is appropriate after gaining hemorrhage control and hemodynamic stability for potentially salvageable kidneys identified during exploration.

- Technique: Complete renal exposure, debridement of non-viable tissue, hemostasis by individual suture ligation of bleeding vessels, watertight closure (absorbable suture), drainage of the collecting system, and coverage/approximation of the parenchymal defect.

- Perform partial nephrectomy if reconstruction is not possible: the collecting system must be closed, and the parenchyma covered with fat or omentum. Consider the use of hemostatic agents and tissue sealants if available.

- Place ureteral stent for persistent urinary extravasation.

Treatment:

- Perform retrograde cystography in patients with gross hematuria and a mechanism concerning for bladder injury or a finding on exam or imaging concerning for bladder rupture or pelvic ring fracture.

- Retrograde cystography can be done by CT or plain film. For CT cystogram, use diluted Conray to reduce scatter artifact from the contrast. A minimum of 300 mL is needed for an adequate study. Another imaging with the bladder emptied of contrast should also be obtained. Plain film images should include a scout film and an AP image with or without oblique views, both with the bladder full and again after it is drained.

- In most cases, extraperitoneal extravasation of contrast can be managed with Foley catheterization alone. Open repair is indicated for complicated ruptures, including pelvic fractures with exposed bone spicules in the bladder and concurrent rectal or vaginal lacerations that may lead to fistula formation. Patients undergoing exploration for other appropriately stable indications and those with significant bladder neck involvement should be considered for closure. A transvesical approach can reduce the disruption of the pelvic hematoma.

- Intraperitoneal rupture requires open repair, two-layer closure with absorbable suture, and perivesical drain placement. A large caliber urethral catheter without a suprapubic catheter is usually sufficient for bladder drainage. Patients with complex lower extremity, pelvic, or perineal injuries and those requiring prolonged immobilization may also benefit from suprapubic catheter drainage.

- Follow up cystography should be performed before catheter removal.

Treatment:

- Identification of ureteral injury requires a high index of suspicion. Therefore, it should be evaluated with IV contrast-enhanced CT with delayed imaging or direct inspection during laparotomy if preoperative imaging is not available.

- Ureteral contusions can be managed by stenting or judicious excision of the injured area with primary anastomosis, depending on its severity. Simple ureteral lacerations should be closed primarily over a stent.

- Complete transections of the ureter proximal to the iliac vessels can be repaired using a tension-free, end-to-end, spatulated anastomosis over a ureteral stent. Transections distal to the vessels should be managed with a ureteral reimplantation over a stent. A psoas hitch or Boari flap may be necessary in some cases.

- In cases of inadequate ureteral length to re-anastomose or hemodynamic instability of the patient intraoperatively, a pediatric feeding tube or open-ended ureteral catheter may be placed in the proximal ureter, brought out through the skin, and placed to closed drainage. Reconstruction of the ureter can then be performed at a future date.

- A ureteropelvic junction avulsion injury should undergo re-anastomosis of the ureter to the renal pelvis over a stent.

- A drain should be considered after ureteral repair.

Treatment:

- The primary goals in managing genital injuries are hemorrhage control and tissue preservation.

- Hemorrhage can occur from small arteries on the dorsal penile shaft or the spermatic cord. These vessels can be managed with precise cautery.

- Large-volume, low-pressure irrigation with normal saline should be performed with each surgical intervention. Delayed wound closure is appropriate for significant injuries with considerable tissue damage. Negative pressure wound dressings are well tolerated but often require creative placement techniques when applied to the genitalia. A non-adherent silicone or hydrophilic white foam dressing can be used to cover exposed testicles or freshly repaired corporal tissue when using a negative pressure dressing.

- Penile injury may include the corpus spongiosum or corpora cavernosa and can result in continued hemorrhage. These can be repaired by approximating the tunical margins with absorbable sutures in a hemostatic fashion following irrigation and debridement of necrotic or devitalized tissue.

- The glans is well vascularized and can generally be closed with interrupted absorbable suture.

- Scrotal injuries are managed similarly to other soft tissue wounds. Small penetrating injuries or blast mechanisms can result in significant testicular damage. There should be a low threshold for BILATERAL surgical exploration in these cases. The scrotum should undergo irrigation and debridement with primary or delayed closure. Widely spaced absorbable suture and a Penrose drain can be used in place of a negative pressure dressing when delayed closure is required.

- Testicle injuries can be diagnosed with a physical exam or scrotal ultrasound. CT or sonography may also show evidence of foreign bodies or air in the scrotum or abnormality of one or both testes. Equivocal cases should be explored. Necrotic testicular tissue should be debrided, and the capsule closed with an absorbable suture. A tunical vaginalis flap can be used when the tunica albuginea is deficient for closure.

Treatment:

- Diagnosis: A RUG should be performed for suspected urethral injury. For partial urethral tears, a single attempt at urethral catheterization with a well-lubricated catheter may be attempted by an experienced provider.

- If unable to perform a RUG and urethral injury is suspected, place a suprapubic catheter.

- Anterior urethral injuries: Primary repair of uncomplicated penetrating injury to the anterior urethra may be performed using fine absorbable sutures with careful mucosal-to-mucosal apposition over a urethral catheter. Immediate repair should not be performed in the setting of extensive tissue damage, urethral loss, patient instability, or surgeon inexperience. Bleeding from the corpus spongiosum can be controlled with site-specific fine absorbable sutures. Bladder drainage should be established by urethral catheterization or suprapubic drainage.

- Posterior urethral injuries: These injuries are typically associated with pelvic fractures or deep penetrating trauma. Suprapubic urinary drainage with delayed reconstruction is the preferred treatment for the majority of cases.

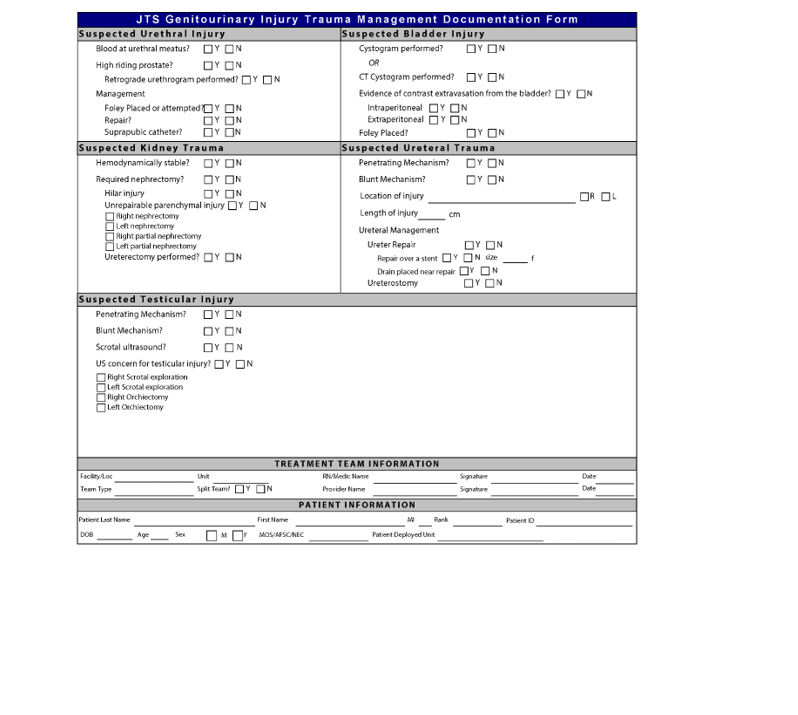

APPENDIX B: JTS GENITOURINARY INJURY TRAUMA MANAGEMENT DOCUMENTATION FORM

APPENDIX C: CLASS VIII MEDICAL MATERIEL

Here is a detailed list of the medical materiel required for the management of genitourinary (GU) trauma:

Basic Supplies

- Sterile Gloves

- Sterile Drapes

- Surgical Masks

- Eye Protection

- Antiseptic Solutions (e.g., Betadine, Chlorhexidine)

- Hand sanitizer

Diagnostic Equipment

- Portable Ultrasound Machine

- X-ray Machine or Access to Radiology Services

- IV Contrast

- Urinalysis Strips

- Microscope

- Retrograde Urethrography Equipment

- Proctoscope

Catheterization and Drainage

- Foley Catheters (various sizes)

- Suprapubic Catheter Kits

- Urine Collection Bags

- Ureteral double J stents – various sizes and lengths

- Pediatric feeding tube (extracorporeal drainage)

- Percutaneous nephrostomy kits

Surgical Instruments and Supplies

- Basic Surgical Instrument Sets: Including scalpels, forceps, scissors, and needle holders.

- Specialized GU Surgery Instruments: Such as renal clamps, ureteral catheters, and penile tourniquets.

- Suture Materials (various sizes and types)

- Staplers and Staple loads/reloads

- Hemostatic Agents

- Wound Irrigation Solutions (e.g., saline, antibiotic solutions)

Blood and Fluid Management

- Massive Transfusion Protocol (MTP) Supplies: Including Whole blood, packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets. Rapid infuser and/or pressure bag for rapid transfusion of blood products.

- IV Fluids (e.g., Ringer’s Lactate, Normal Saline)

- Intravenous Access Kits: Including 8.5 Fr central venous catheter and large bore peripheral IV catheters.

- Blood Pressure Monitors and Automated Blood Pressure Cuffs

Postoperative Care

- Pain Management Supplies: Including opioids and non-opioid analgesics, as well as nerve blocks.

- Antibiotics: Broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Wound Dressing Supplies: Including gauze, bandages, and tape.

- Physical/Occupational Therapy Equipment

Additional Considerations

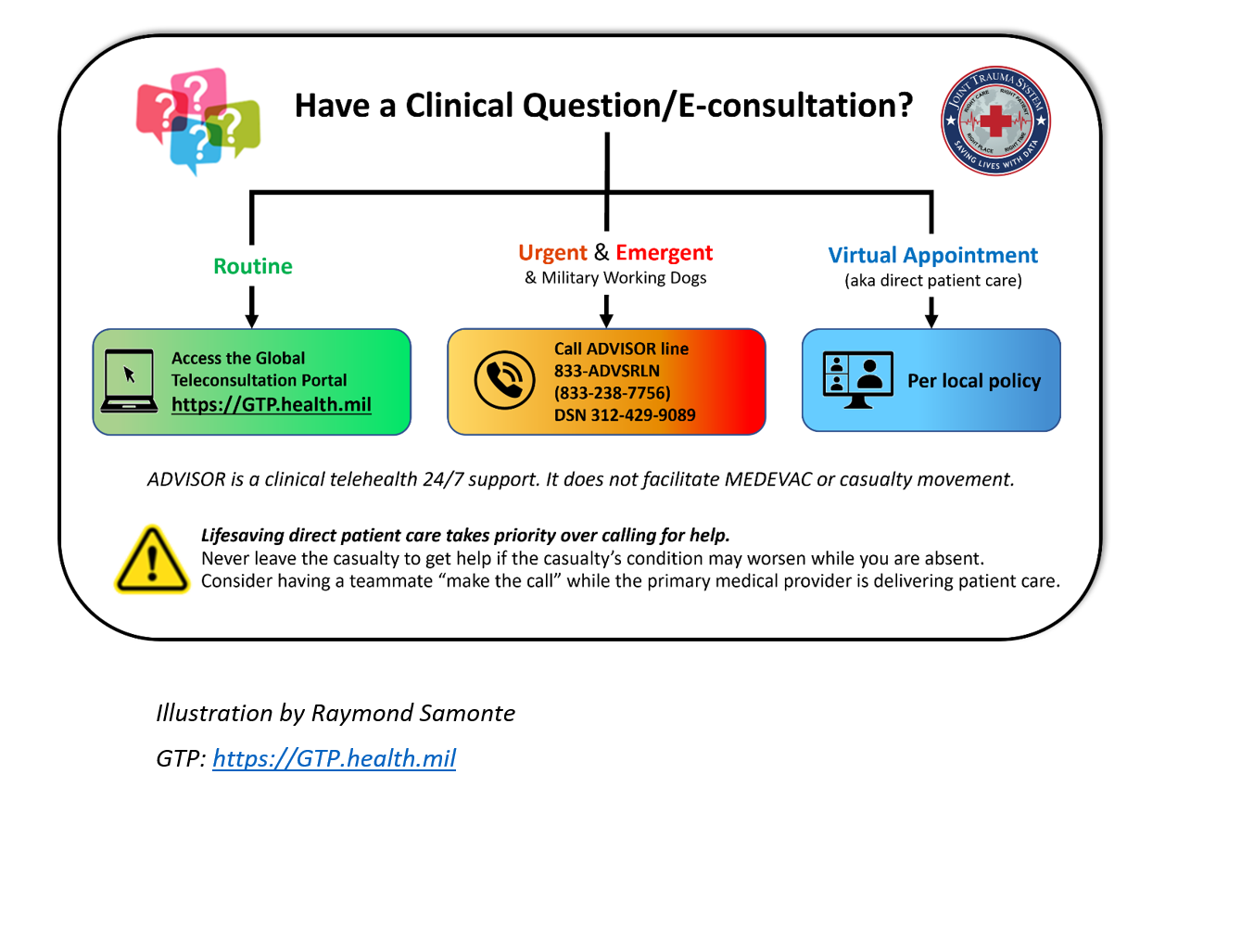

- Telemedicine Equipment: For remote consultations with specialists, particularly in the absence of urology support.

- Documentation Supplies: JTS Genitourinary Injury Trauma Management Documentation Form, pens, and electronic health record access.

References and Protocols

- Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Guidelines

- Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) Guidelines

- GU Injury Trauma Management Clinical Practice Guidelines

This list covers the basic to advanced needs for managing GU injuries in a military or combat setting, ensuring that healthcare providers have the necessary tools to perform life-saving interventions and facilitate the recovery and rehabilitation of patients.

For additional information including National Stock Number (NSN), please contact dha.ncr.med-log.list.lpr-cps@health.mil

DISCLAIMER: This is not an exhaustive list. These are items identified to be important for the care of combat casualties.

APPENDIX D: TELEMEDICINE/TELECONSULTATION

APPENDIX E: INFORMATION REGARDING OFF-LABEL USES IN CPGS

PURPOSE

The purpose of this Appendix is to ensure an understanding of DoD policy and practice regarding inclusion in CPGs of “off-label” uses of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products. This applies to off-label uses with patients who are armed forces members.

BACKGROUND

Unapproved (i.e., “off-label”) uses of FDA-approved products are extremely common in American medicine and are usually not subject to any special regulations. However, under Federal law, in some circumstances, unapproved uses of approved drugs are subject to FDA regulations governing “investigational new drugs.” These circumstances include such uses as part of clinical trials, and in the military context, command required, unapproved uses. Some command requested unapproved uses may also be subject to special regulations.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING OFF-LABEL USES IN CPGS

The inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is not a clinical trial, nor is it a command request or requirement. Further, it does not imply that the Military Health System requires that use by DoD health care practitioners or considers it to be the “standard of care.” Rather, the inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is to inform the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner by providing information regarding potential risks and benefits of treatment alternatives. The decision is for the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner within the practitioner-patient relationship.

ADDITIONAL PROCEDURES

Balanced Discussion

Consistent with this purpose, CPG discussions of off-label uses specifically state that they are uses not approved by the FDA. Further, such discussions are balanced in the presentation of appropriate clinical study data, including any such data that suggest caution in the use of the product and specifically including any FDA-issued warnings.

Quality Assurance Monitoring

With respect to such off-label uses, DoD procedure is to maintain a regular system of quality assurance monitoring of outcomes and known potential adverse events. For this reason, the importance of accurate clinical records is underscored.

Information to Patients

Good clinical practice includes the provision of appropriate information to patients. Each CPG discussing an unusual off-label use will address the issue of information to patients. When practicable, consideration will be given to including in an appendix an appropriate information sheet for distribution to patients, whether before or after use of the product. Information to patients should address in plain language: a) that the use is not approved by the FDA; b) the reasons why a DoD health care practitioner would decide to use the product for this purpose; and c) the potential risks associated with such use.