Prolonged Casualty Care Guidelines

JTS/CoTCCC/PCC WG

PROLONGED CASUALTY CARE BACKGROUND

The need to provide patient care for extended periods of time when evacuation or mission requirements surpass available capabilities and/or capacity to provide that care.

The PCC guidelines are a consolidated list of casualty-centric knowledge, skills, abilities, and best practices intended to serve as the DoD baseline clinical practice guidance (CPG) to direct casualty management over a prolonged period of time in austere, remote, or expeditionary settings, and/or during long-distance movements. These PCC guidelines build upon the DoD standard of care for non-medical and medical first responders as established by the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC), outlined in the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines,1 and in accordance with (IAW) DoDI 1322.24.

The guidelines were developed by the PCC Work Group (PCC WG). The PCC WG is chartered under the Defense Committee on Trauma (DCoT) to provide subject matter expertise supporting the Joint Trauma System (JTS) mission to improve trauma readiness and outcomes through evidence-driven performance improvement. The PCC WG is responsible for reviewing, assessing, and providing solutions for PCC-related shortfalls and requirements as outlined in DoD Instruction (DoDI) 1322.24, Medical Readiness Training, 16 Mar 2018, under the authority of the JTS as the DoD Center of Excellence pursuant to DoDI 6040.47, JTS, 05 Aug 2018.

Operational and medical planning should seek to avoid categorizing PCC as a primary medical support capability or control factor during deliberate risk assessment; however, an effective medical plan always includes PCC as a contingency. Ideally, forward surgical and critical care should be provided as close to casualties as possible to optimize survivability.2 DoD units must be prepared for medical capacity to be overwhelmed, or for medical evacuation to be delayed or compromised. When contingencies arise, commanders’ casualty response plans during PCC situations are likely to be complex and challenging. Therefore, PCC planning, training, equipping, and sustainment strategies must be completed prior to a PCC event. The following evidence-driven PCC guidelines are designed to establish a systematic framework to synchronize critical medical decisions points into an executable PCC strategy, regardless of the nature of injury or illness, to effectively manage a complex patient and to advise commanders of associated risks.

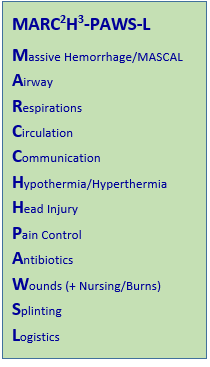

The guidelines build upon the accepted TCCC categories framed in the novel MARC2H3-PAWS-L treatment algorithm, (Massive Hemorrhage/MASCAL, Airway, Respirations, Circulation, Communications, Hypo/Hyperthermia and Head Injuries, Pain Control, Antibiotics, Wounds (including Nursing and Burns), Splinting, Logistics).

The PCC guidelines prepare the Service Member for “what to consider next” after all TCCC interventions have been effectively performed and should only be trained after having mastering the principles and techniques of TCCC.

The guidelines are a consolidated list of casualty-centric knowledge, skills, abilities, and best practices are the proposed standard of care for developing and sustaining DoD programs required to enhance confidence, interoperability, and common trust among all PCC-adept personnel across the Joint force.

The JTS CPGs are foundational to the PCC guidelines and will be referenced throughout this document in an effort to keep these guidelines concise. General information on the Joint Trauma System is available on the JTS website (https://jts.health.mil) and links to all of the CPGs are also available by using the following link: https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/PI_CPGs/cpgs.

The TCCC guidelines are included in these guidelines as an attachment because they are foundational AND prerequisite to effective PCC. Remember, the primary goal in PCC is to get out of PCC!!!

PCC PRINCIPLES

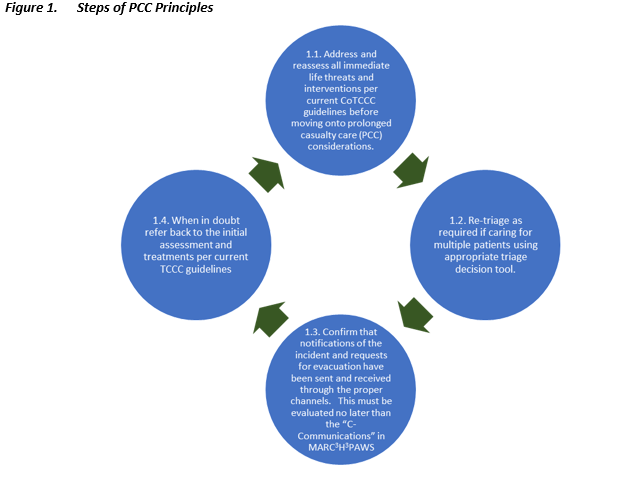

The principles and strategies of providing effective prolonged casualty care are meant to help organize the overwhelming amount of critical information into a clear clinical picture and proactive plan regardless of the nature of injury or illness. The following steps can be implemented in any austere environment from dispersed small team operations in permissive environments to large scale combat operations to make the care of a critically ill patient more efficient for the medic and their team. These mimic the systems and processes in typical intensive care units without relying on technology while leaving the ability to add technological adjuncts as they become available. The following checklist is meant to emphasize some of the most important principles in efficient care of the critically ill patient.

1. Perform initial lifesaving care using TCCC guidelines and continue resuscitation. The foundation of good PCC is mastery of TCCC and a strong foundation in clinical medicine.

2. Delineate roles and responsibilities, including naming a team leader. A leader should be appointed who will manage the larger clinical picture while assistants focus on attention intensive tasks.

3. Perform comprehensive physical exam and detailed history with problem list and care plan. After initial care and stabilization of a trauma or medical patient, a detailed physical exam and history should be performed for the purpose of completing a comprehensive problem list and corresponding care plan.

4. Record and trend vital signs. Vital signs trending should be done with the earliest set of vital signs taken and continued at regular intervals so that the baseline values can be compared to present reality on a dedicated trending chart.

5. Perform a teleconsultation. As soon as is feasible, the medic should prepare a teleconsultation by either filling out a preformatted script or by writing down their concerns along with the latest patient information.

6. Create a nursing care plan. Nursing care and environmental considerations should be addressed early to limit any provider-induced iatrogenic injury.

7. Implement team wake, rest, chow plan. The medic and each of their first responders should make all efforts to take care of each other by insisting on short breaks for rest, food, and mental decompression.

8. Anticipate resupply and electrical issues

9. Perform periodic mini rounds assessments. Stepping back from the immediate care of the patient periodically and re-engaging with a mini patient round and review of systems can allow the medic to recognize changes in the condition of the patient and reprioritize interventions.

- Is the patient stable or unstable?

- Is the patient sick or not sick?

- Is the patient getting better or getting worse?

- How is this assessment different from the last assessment?

10. Obtain and interpret lab studies. When available, labs may be used to augment these trends and physical exam findings to confirm or rule out probable diagnoses.

11. Perform necessary surgical procedures. The decision to perform invasive and surgical interventions should consider both risks and benefit to the patient’s overall outcome and not merely the immediate goal.

12. Prepare for transportation or evacuation care. If the medic is caring for the patient over a long tactical move or strategic evacuation, they should be prepared with ample drugs, fluids, supplies and be ready for all contingencies in flight.

13. Prepare documentation for patient handover. The preparation for transportation and evacuation care should begin immediately upon assuming care for the patient and should include hasty and detailed evacuation requests up both the medical and operational channels with the goal of getting the patient to the proper role of care as soon as possible.

Guideline User Notes

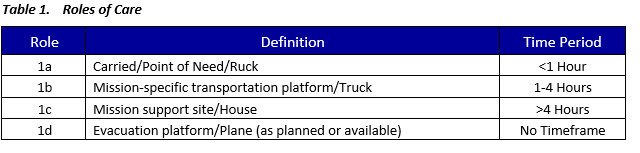

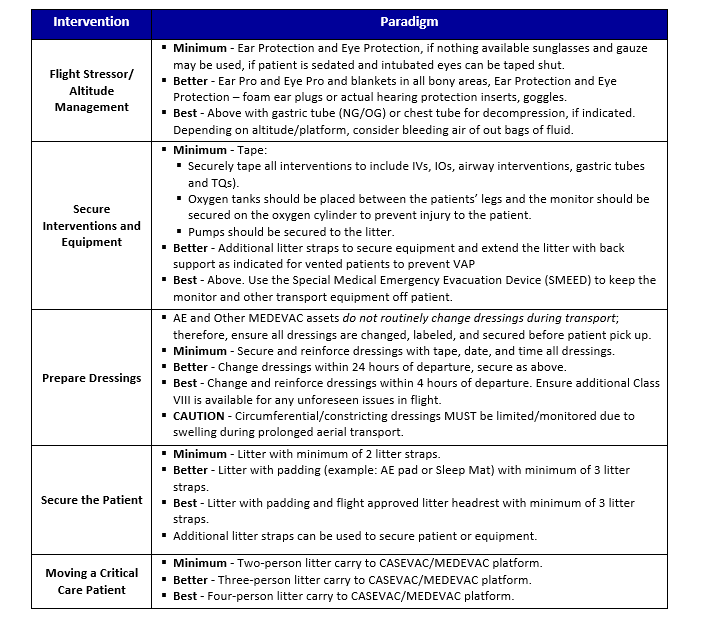

PCC operational context uses the following paradigm for phases of care for different periods of time one is in a PCC scenario:

Where appropriate, a minimum-better-best format is included for situations in which the operational reality precludes optimal care for a given scenario:

- Minimum: This is the minimum level of care which should be delivered for a specified level of capability

- Better: When available or practical, this includes treatment strategies or adjuncts that improve outcomes while still not considered the standard of care.

- Best: This is the optimal medical for a given scenario based on the level of medical expertise of the provider

Expectations of prehospital care, based on TCCC's role-based standard of care, are included within each section:

- Tier 1: This is the basic medical knowledge for all service-members.

- Tier 2: Those who have been through approved CLS training are expected to be able to meet the standards at this level of care.

- Tier 3 (Combat Medics/Corpsmen [CMC]): Those who are trained medics/corpsmen are expected to meet the medical standards for this tier.

- Tier 4 (Combat Paramedic/Provider [CPP]): This is the highest level of prehospital capability and will have a significantly expanded scope of practice.

MASCAL/TRIAGE - PCC

Background

The foundation of effective PCC is accurate triage for both treatment in the PCC setting and for transportation to a higher level of care, as well as effective resource management across the entire trauma system. Resource management includes the appropriate utilization of medical and non-medical personnel, equipment and supplies, communications, and evacuation platforms. Like most Mass Casualty incidents (MASCAL), the purpose of triage in a PCC setting is to swiftly identify casualty needs for optimal resource allocation in order to improve patient outcomes. However, PCC presents unique and dynamic triage challenges while managing casualties over a prolonged period with a low likelihood of receiving additional medical supplies or personnel with enhanced medical capabilities apart from pre-established networks. MASCAL in a PCC environment will necessitate more conservative resource allocation than traditional MASCAL in mature theaters or fixed medical facilities where damage control surgery, intensive care, and medical logistical support are more readily available, and resupply is more likely. PCC dictates the need for implementing various triage and resource management techniques to ensure the greatest good for all. The objectives and basic strategies are the same for all MASCAL; however, tactics will vary depending on the available resources and situations.

MASCAL Decision Points

1. Determine if a PCC MASCAL is occurring – do the requirements for care exceed capabilities?

- What is the threat? Has it been neutralized or contained? If not, security takes priority.

- What is the total casualty estimate?

- Are there resource limitations that will affect survival?

- Can medical personnel arrive at the casualty location, or can the casualty move to them?

- Is evacuation possible?

- Communicate the situation to all available personnel conducting or enabling PCC.

- Assess requirements for which class of triage you are facing (see Appendix C) and scale medical action to maximize lethality then survivability.

- Remain agile and be ready to move based on the mission.

2. Determine if conditions require significant changes in the commonly understood and accepted standards of care (Crisis Standards of Care)3 or if personnel who are not ordinarily qualified for a particular medical skill will need to deliver care. MASCAL in PCC requires both medical and non-medical responders initially save lives and preserve survivable casualties. Both groups will need skills traditionally outside existing paradigms, such as non-medical personnel taking and record vital signs or Tier 3 TCCC medical personnel maintaining vent settings on a stable patient. The MASCAL standard of care will be driven by the volume of casualties, resources, and risk or mortality/morbidity due to degree of injury/illness; as such, remain agile throughout the MASCAL and trend in both directions based upon resources available.

3. MASCAL management is often intuitive and reactive (due to lack of full mission training opportunities) and should rely on familiar terminology and principles. Treatment and casualty movement should be rehearsed to create automatic responses.

4.. The tactical and strategic operational context will underpin every facet of MASCAL in a PCC environment, operational commanders MUST be involved in every stage of MASCAL response (The mere fact that a medical professional or team of medical professionals is forced to hold a casualty longer than doctrinal planning timelines means there is a failure in the operational/logistical evacuation chain. Battle lines, ground-to-air threat, etc. levels may have shifted.)

5. Logistical resupply may need to include non-standard means and involve personnel and departments not typically associated with Class VIII in other situations (i.e. aerial resupply, speedballs, caches, local national market procurement).

6. The most experienced person should establish MASCAL roles and responsibilities, as appropriate.

- Usually, simpler is better.

- Focus on those that will preserve scarce resources, such as blood.

- Triage is a continuous process and should be repeated as often as is clinically and operationally practical.

- Avoid high resource and low yield interventions.

- Emergency airway interventions should prioritize REVERSIBLE pathology in salvageable patients.

- Decisions will depend on available resources and skillsets (i.e. penetrating traumatic brain injury [TBI] triaged differently if no neurosurgery is available in a timely manner or at all in theater).

- Conserve, ration, and redistribute additional scarce resources (i.e. blood, drug).

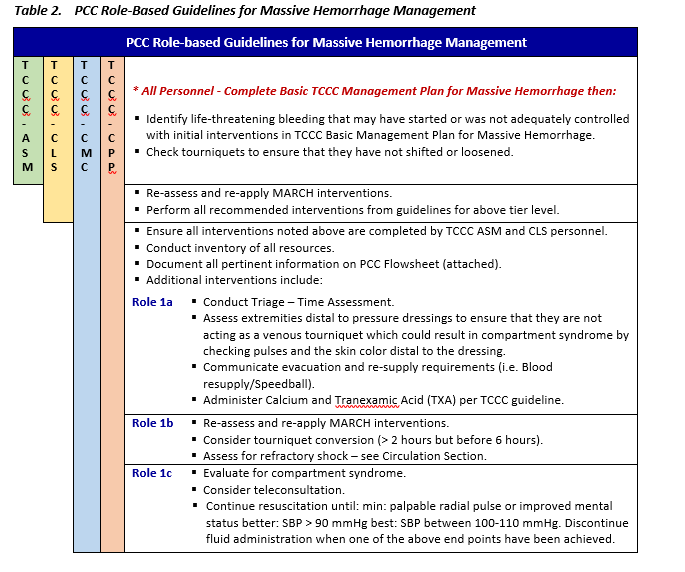

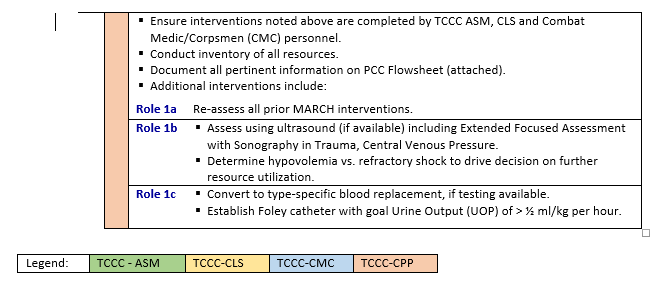

MASSIVE HEMORRHAGE - PCC

Early recognition and intervention for life-threatening hemorrhage are essential for survival. The immediate priorities are to control life-threatening hemorrhage and maintain vital organ perfusion with rapid blood transfusion.4

Pre-deployment, Mission Planning, and Training Considerations

- Conduct unit level blood donor testing (for blood typing, transfusion transmitted diseases and Low Titer blood type O titers) and develop operational roster.

- Define Cold Chain Stored Whole Blood (CSWB) distribution quantities in area of responsibility.

- Manage and equip prehospital blood storage program if unit policies and procedures allow for prehospital blood storage.

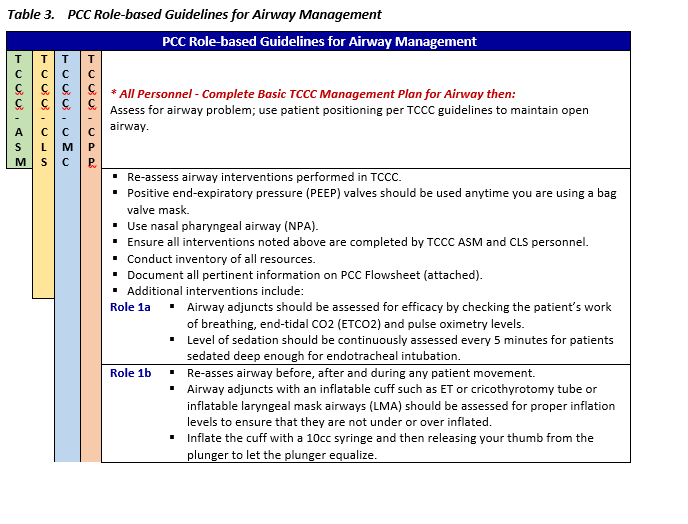

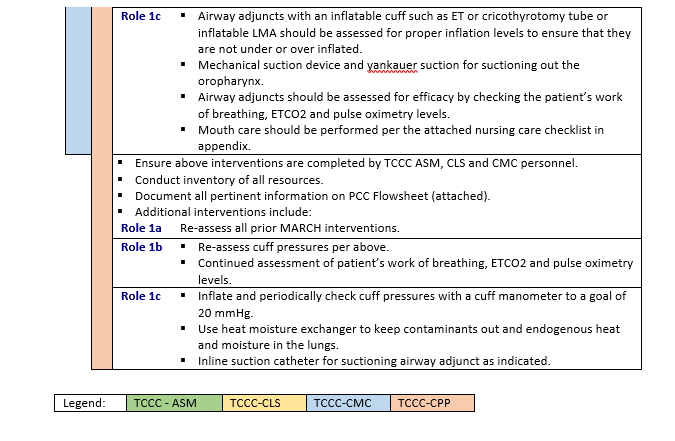

AIRWAY MANAGEMENT - PCC

Background

Airway compromise is the second leading cause of potentially survivable death on the battlefield after hemorrhage.6 Complete airway occlusion can cause death from suffocation within minutes. Austere environments present significant challenges with airway management. Limited provider experience and skill, equipment, resources, and medications shape the best management techniques. Considerations include: limited availability of supplemental oxygen; medications for induction/rapid sequence intubation, paralysis, and post-intubation management; and limitations in available equipment. Another reality is limitations in sustainment training options, especially for advanced airway techniques. Due to these challenges, some common recommendations that may be considered “rescue” techniques in standard hospital airway management may be recommended earlier or in a non-standard fashion to establish and control an airway in a PCC environment. Patients who require advanced airway placement tend to undergo more interventions, be more critically injured, and ultimately have a higher proportion of deaths. The ability to rapidly and consistently manage an airway when indicated, or spend time on other resuscitative needs when airway management is not indicated, may contribute to improved outcomes.7,8

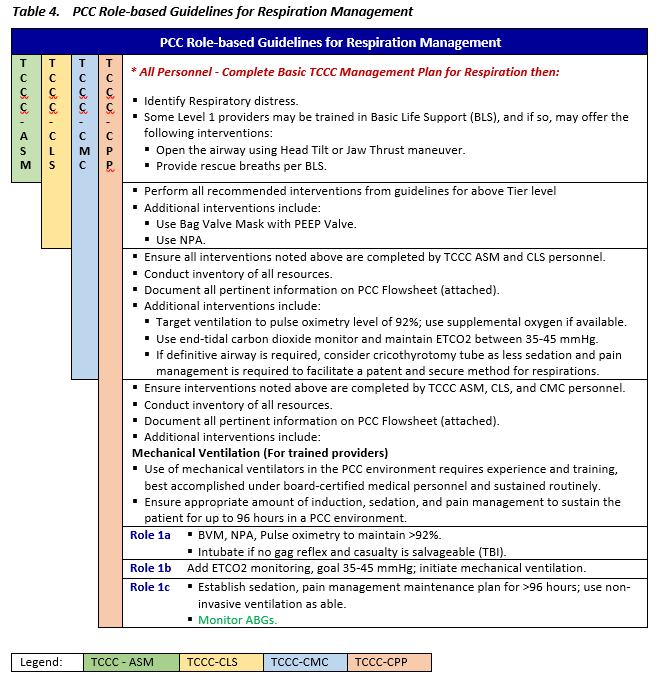

RESPIRATION AND VENTILATION - PCC

Respiration is the process of gas exchange at the cellular level. Oxygen is conducted into the lung and taken up by the blood via hemoglobin to be transported throughout the body. In the peripheral tissues, carbon dioxide is exchanged for oxygen, which is transported by the blood to the lungs, where it is exhaled. This process is essential to cellular and organism survival. Dysfunction of this process is a feature of multiple-injury patterns that can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

Additional Considerations

- When in a PCC environment, simple monitoring technologies are able to be used by most providers in each of the provider categories to ensure adequate gas exchange and oxygen delivery. Peripheral oxygen saturation can be measured using a pulse oximeter which provides a measurement of hemoglobin saturation and, by inference, the effectiveness of measures to oxygenate a patient. Ventilation can be monitored with end-tidal carbon dioxide. The use of these tools together in a PCC environment provides estimates of oxygen transport to the cells, tissue metabolism, and adequacy of ventilation.

- Providers in the PCC environment can adopt, implement, monitor, and sustain respiration using concepts of manipulating minute ventilation (respiratory rate multiplied by tidal volume). Put simply, it is the number of times a patient is breathing each minute multiplied by the amount of air breathed in with each breath.

- Support of adequate minute ventilation can be performed in an escalating algorithm with rescue breathing, bag valve mask assisted ventilation, and mechanical ventilation. Each of these methods may require escalation of airway management skills and respiratory skills. Manipulation of any of the variables of minute ventilation will alter gas exchange. Therefore, medical providers in the PCC environment at all levels will need to be competent with the monitoring devices appropriate to their level of training. At a minimum, all providers with specific medical training should be competent to use and interpret the previous paragraph's monitoring devices.

- The causes of respiratory failure can overlap and become confusing. When in doubt and whenever possible, initiate a Telemedicine Consultation for further guidance and input.

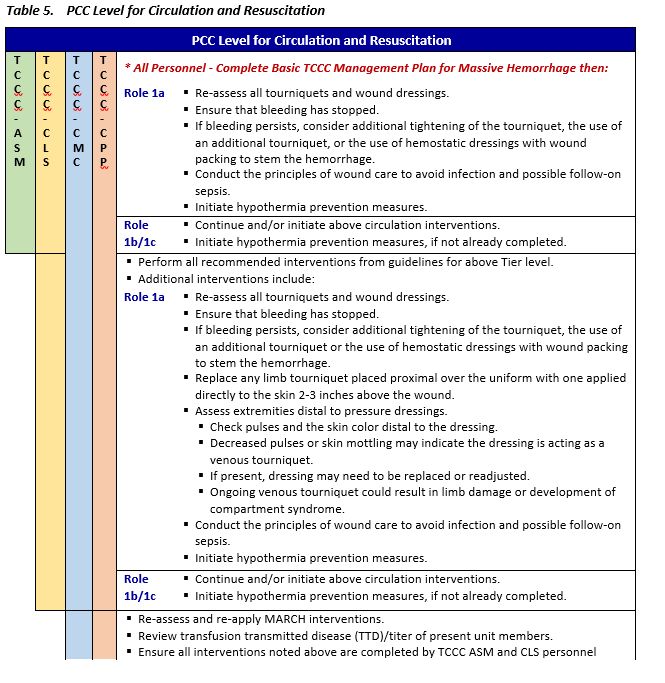

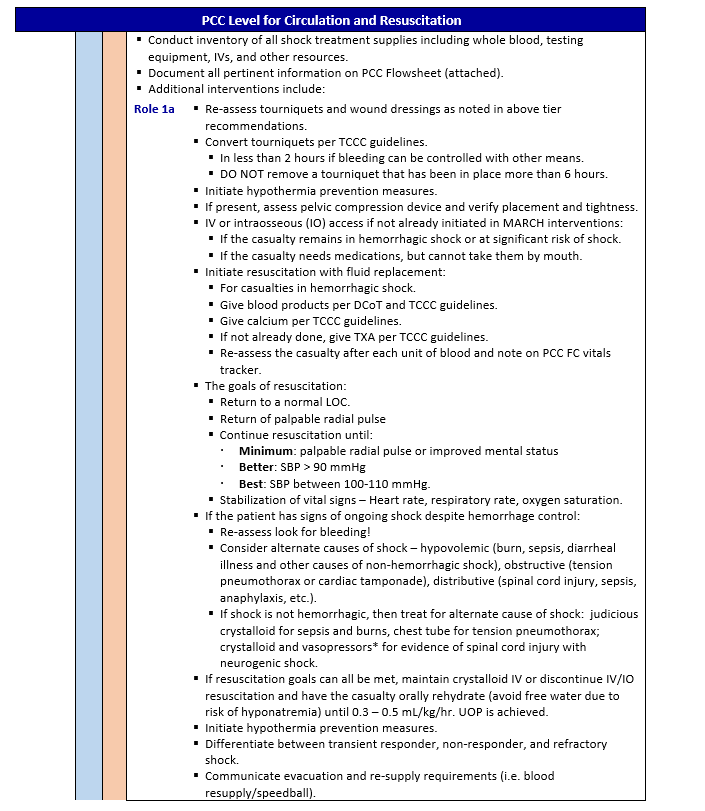

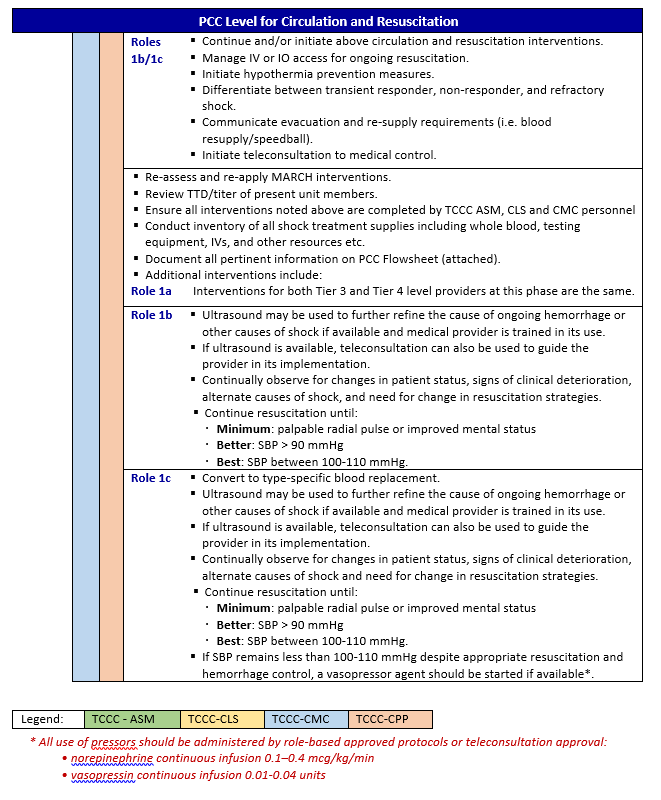

CIRCULATION AND RESUSCITATION - PCC

PCC presents a unique challenge for implementing damage control resuscitation (DCR) as defined by the JTS guideline. PCC goes beyond DCR and should bridge the gap between the prevention of death, the preservation of life, and definitive care. The goals are a return to a normal level of consciousness (LOC), increase and stabilization of systolic blood pressure at 100 - 110 mm Hg when appropriate, and stabilization of vital signs – Heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, etc.

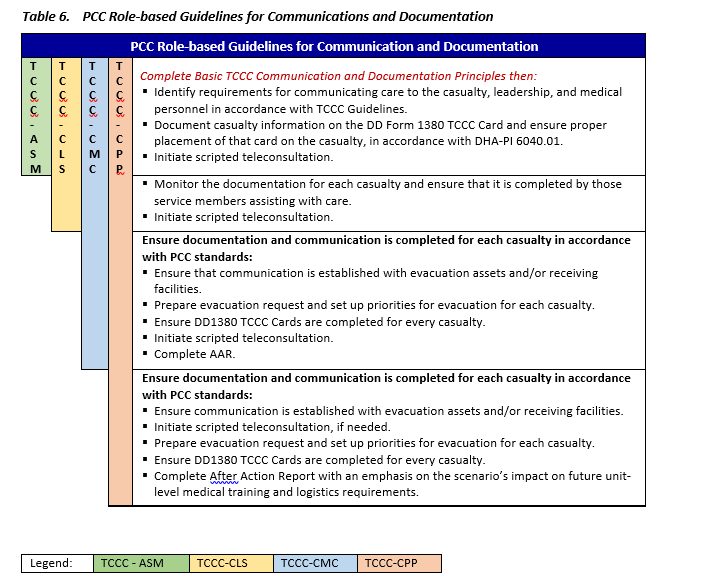

COMMUNICATION AND DOCUMENTATION - PCC

Background

Communication and documentation in PCC are linked priorities as they are activities that are synergistic. For instance, the standard documentation forms (see below) that are used to track the important medical interventions and trends are the recommended scripts that are used in a teleconsultation. Effective documentation leads to effective communication, both in the immediate PCC environment and as a long-term medical management tool for the casualty.

Communication

- Communicate with the casualty if possible. Encourage, reassure, and explain care.

- Communicate with tactical leadership as soon as possible and throughout casualty treatment as needed. Provide leadership with casualty status and evacuation requirements to assist with coordination of evacuation assets.

- Verify evacuation request has been transmitted and establish communication with the evacuation platform as soon as tactically feasible relaying: mechanism of injury, injuries sustained, signs/symptoms, treatments rendered, and other information as appropriate. Have a rehearsed script to relay vital information to the next echelon of care prioritize interventions that cannot be seen by the next provider, such as medications.

- Ensure appropriate notification up the chain of command that PCC is being conducted; requesting support based on the MASCAL decision points.

- Call for teleconsultation as early and as often as needed (e.g., higher medical capability in the Chain of Command, the Advanced VIrtual Support for OpeRational Forces system line, etc.).

- Remember, communication of the situation and medical interventions that have been done and are ongoing includes both teleconsultation and the “handoff report.”

Documentation of Care

- There are 3 levels of documentation, categorized in a minimum, better, best format:

- Minimum - Documentation of care on the TCCC card (DD1380).

- Better - Utilization of a standard PCC flowsheet (if available), example attached.

- Best - Completion of a formal After Action Report (AAR) after patient handoff.

- Transfer documented clinical assessments and treatments rendered. If the availably to scan and/or transmit this information to all parties involved teleconsultation (using all approved and available means), do so for them to have as much of the information as possible.

- Perform a detailed head-to-toe assessment and record all findings as a problem list so that a comprehensive care plan can then be constructed using the attached flow sheet.

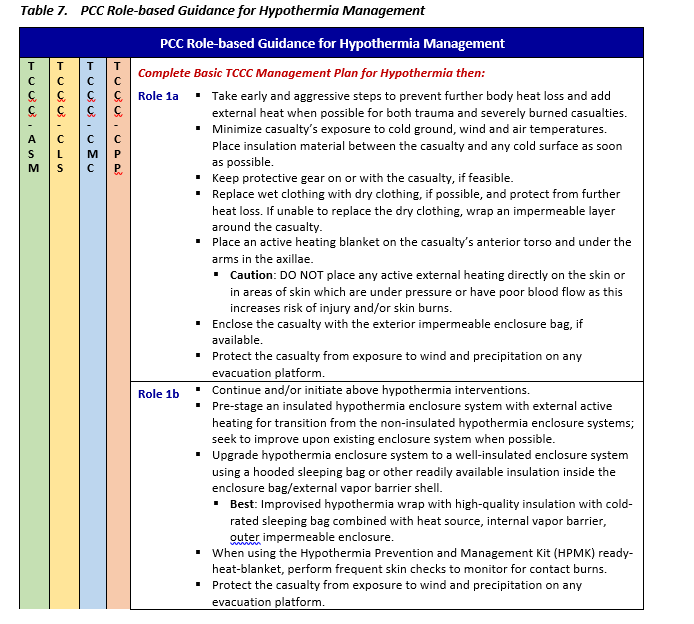

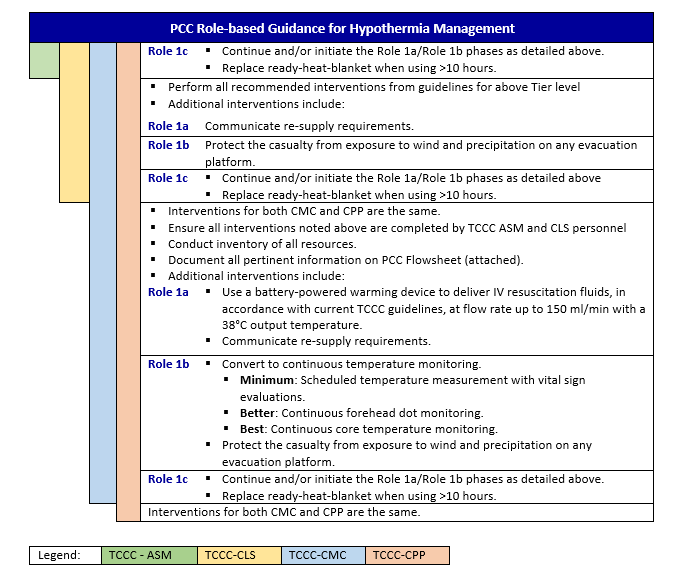

HYPOTHERMIA - PCC

Prevention of hypothermia must be emphasized in combat operations and casualty management at all levels of care. Hypothermia occurs regardless of the ambient temperature; hypothermia can, and does, occur in both hot and cold climates. Because of the difficulty, time, and energy required to actively re-warm casualties, significant attention must be paid to preventing hypothermia from occurring in the first place. Prevention of hypothermia is much easier than treatment of hypothermia; therefore prevention of heat loss should start as soon as possible after the injury. This is optimally accomplished in a layered fashion with rugged, lightweight, durable products that are located as close as possible to the point of injury, and then utilized at all subsequent levels of care, including ground and air evacuation, through all levels of care.12

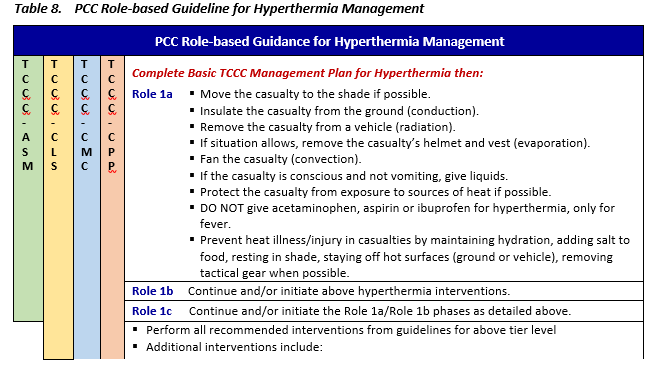

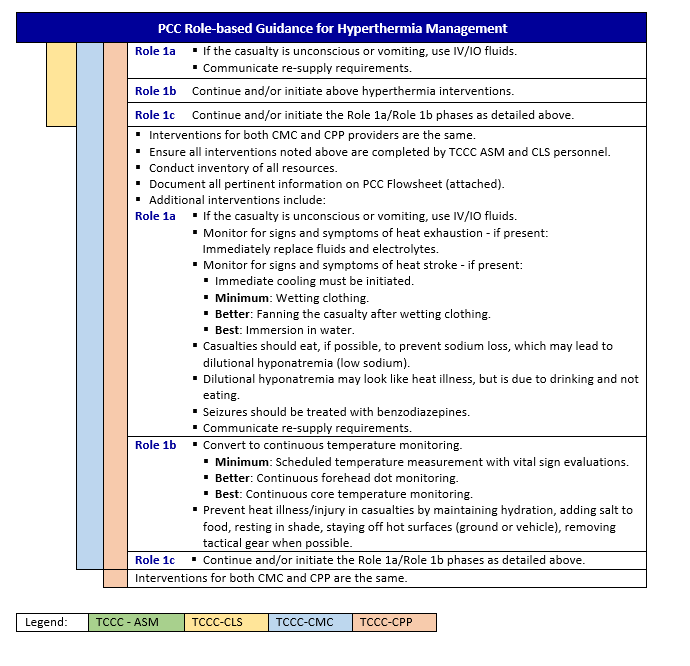

HYPERTHERMIA - PCC

Background

- Hyperpyrexia is elevated body temperature.

- Fever is elevated body temperature in response to a change in hypothalamic set point (infections).

- Hyperthermia is elevated body temperature without a change in hypothalamic set point (heat illness, hyperthyroid, drugs).

- The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that heat flows from hot to cold.

- Heat transfer can occur through several processes:

a. Radiation

b. Conduction

c. Convection

d. Evaporation

Heat exhaustion

Symptoms: weak, dizzy, nauseated, headache, sweating, normal mental status. Heat exhaustion requires replacement of fluids and electrolytes.

Heat stroke

Symptoms: Hyperthermia + mental status changes. Heat stroke requires immediate cooling.

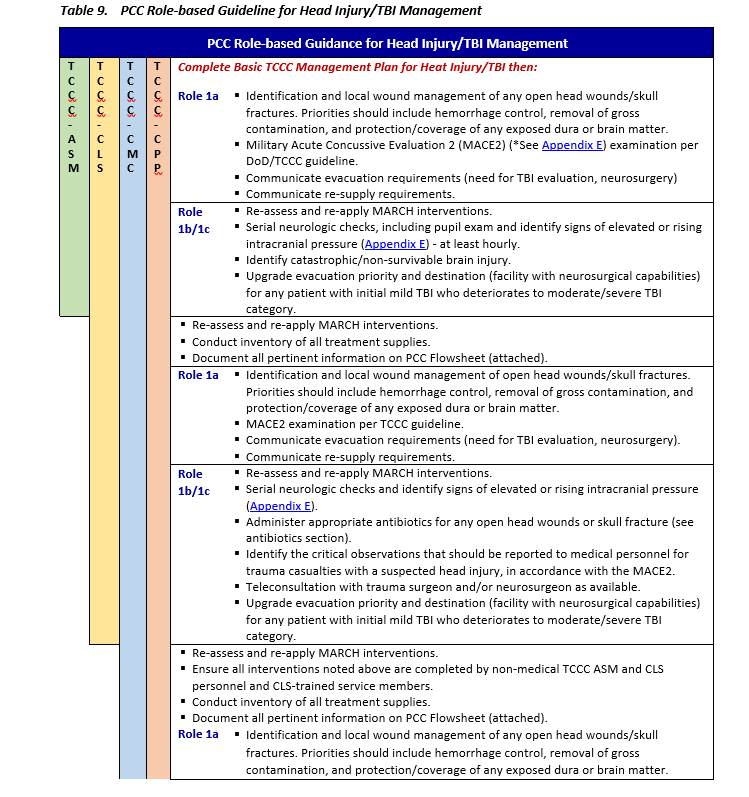

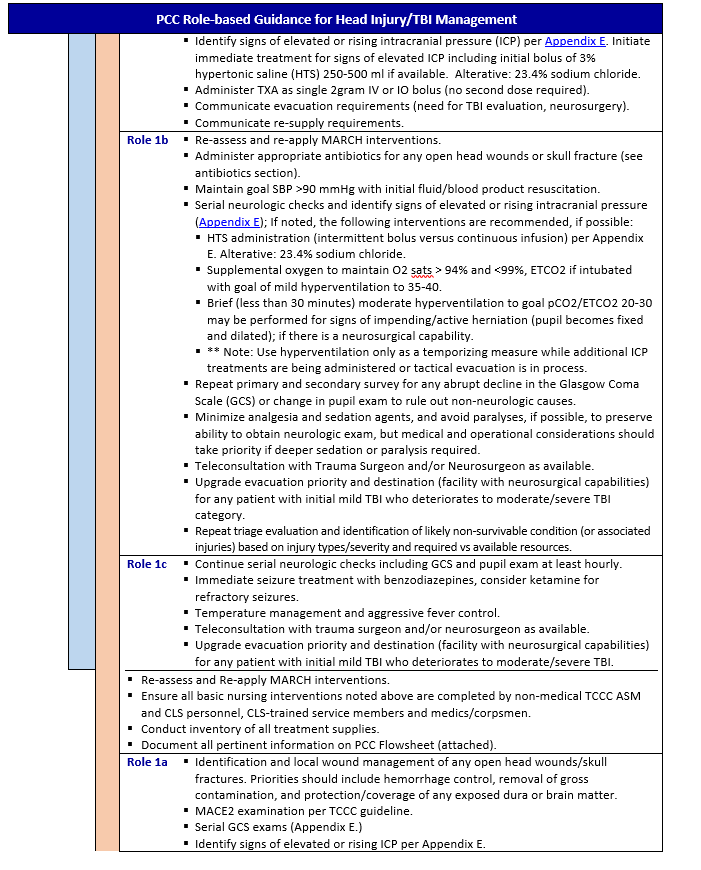

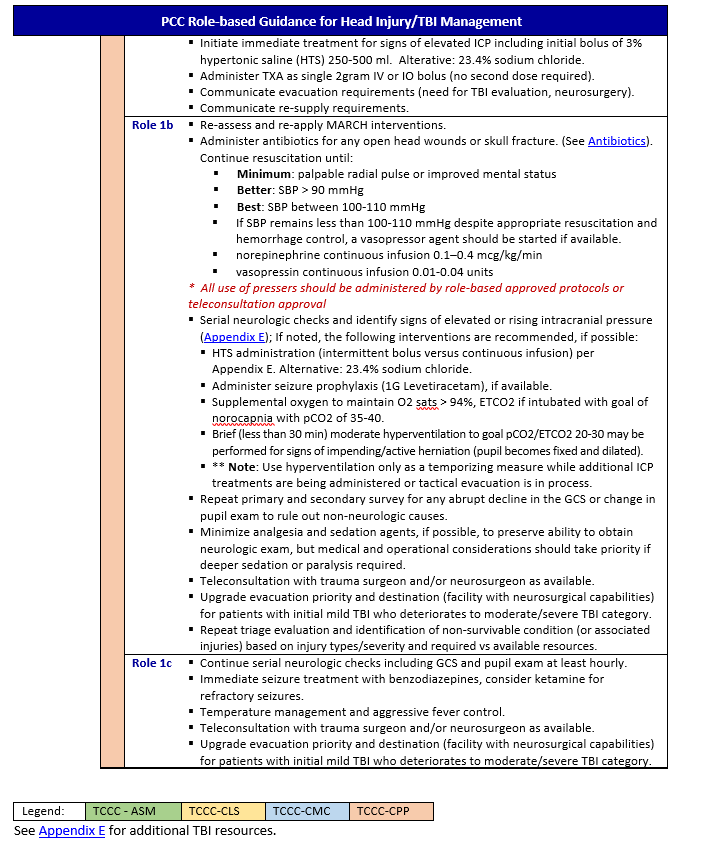

HEAD INJURY/TBI - PCC

Background

TBI occurs when external mechanical forces impact the head and cause an acceleration/deceleration of the brain within the cranial vault which results in injury to brain tissue. TBI may be closed (blunt or blast trauma) or open (penetrating trauma).13 Signs and symptoms of TBI are highly variable and depend on the specific areas of the brain affected and the injury severity. Alteration in consciousness and focal neurologic deficits are common. Various forms of intracranial hemorrhage, such as epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and hemorrhagic contusion can be components of TBI. The vast majority of TBIs are categorized as mild and are not considered life threatening; however, it is important to recognize this injury because if a patient is exposed to a second head injury while still recovering from a mild TBI, they are at risk for increased long-term cognitive effects. Moderate and severe TBIs are life-threatening injuries.

Pre-deployment, Mission Planning, and Training Considerations

- Conduct unit level TTD/Titer testing and develop an operational roster.

- Conduct baseline neurocognitive assessment per Service guideline.

- When possible and practical, keep patient in an elevated orientation to approximately 30 degrees while maintaining C-spine precautions (as clinically indicated) and airway control (don’t just elevate the head by bending the neck).

- Define CSWB distribution quantities in area of responsibility.

- Determine feasibility and requirement for pre-deployment unit level blood draw.

- Conduct unit level pre-deployment blood draw as required.

- Ensure critical head-injury adjunct medications appropriately stocked and storage requirements met.

Treatment Guidelines

*Link to Traumatic Brain Injury in Prolonged Field Care, 6 December 2017 CPG 14

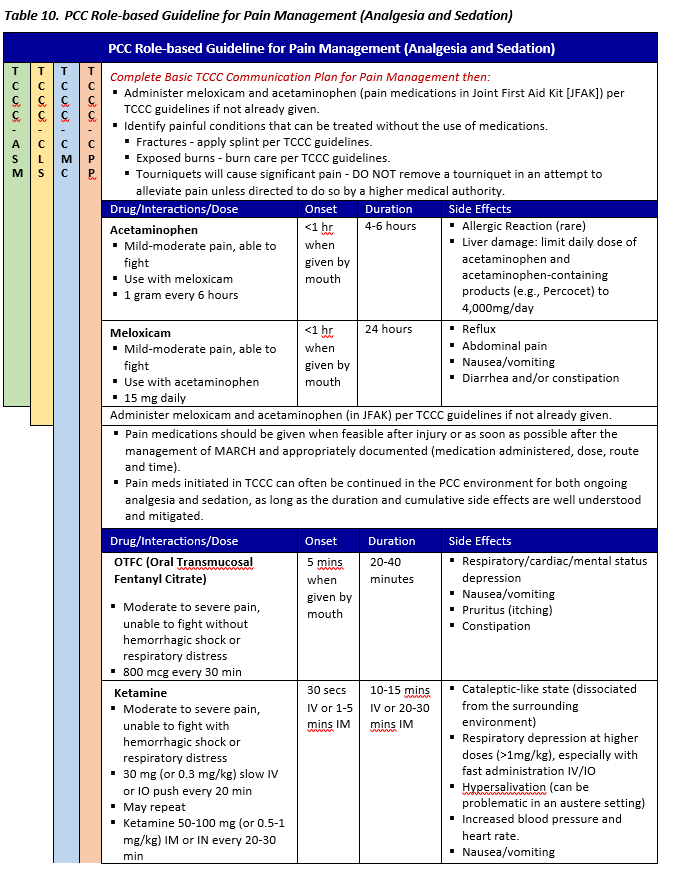

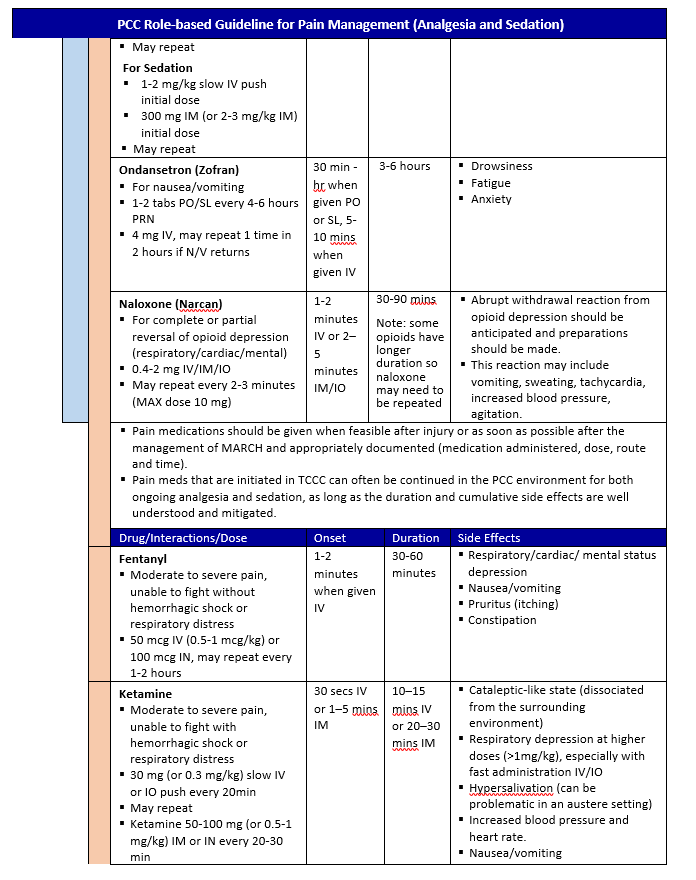

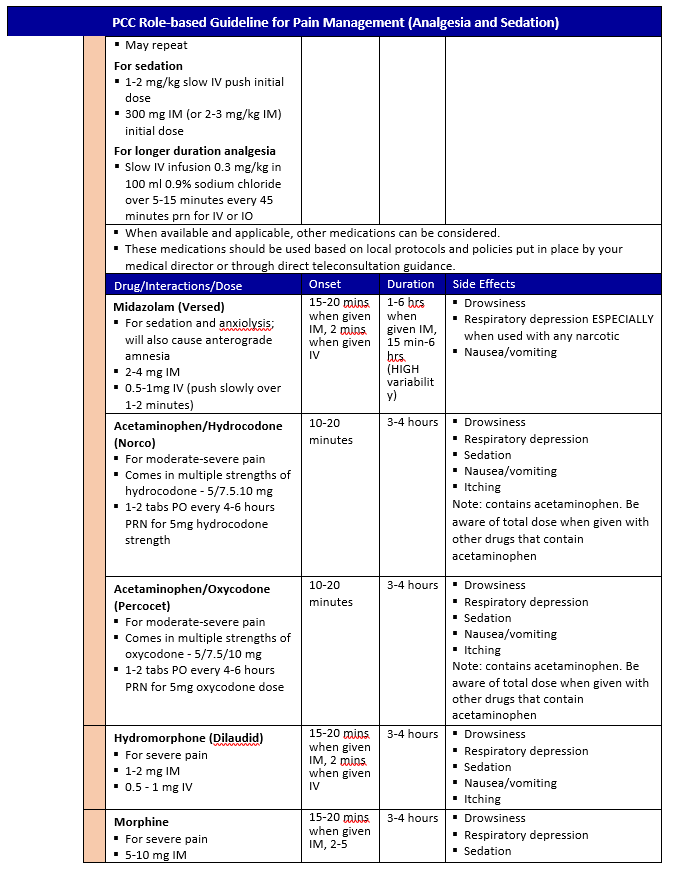

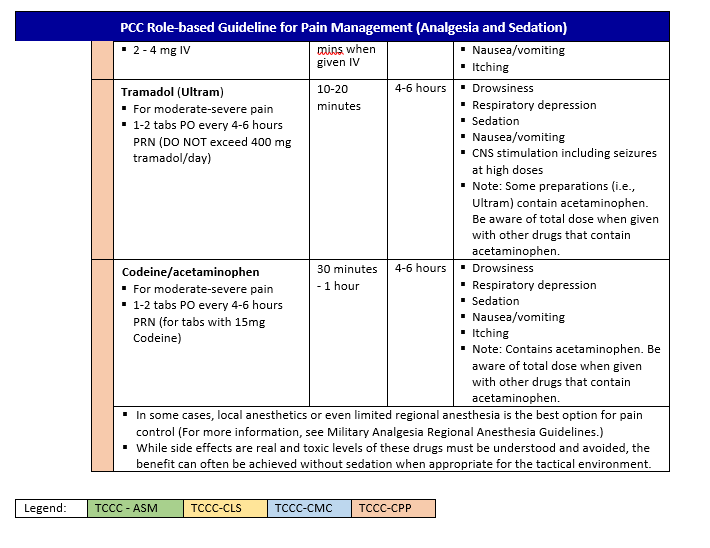

PAIN MANAGEMENT (ANALGESIA AND SEDATION) FOR PCC

Background

A provider of PCC must first and foremost be an expert in TCCC and then be able to identify all the potential issues associated with providing analgesia with or without sedation for a prolonged (4-48 hr.) period.

These PCC pain management guidelines are intended to be used after TCCC Guidelines at the Role 1 setting, when evacuation to higher level of care is not immediately possible. They attempt to decrease complexity by minimizing options for monitoring, medications, and the like, while prioritizing experience with a limited number of options versus recommending many different options for a more customized fashion. Furthermore, it does not address induction of anesthesia before airway management (i.e. rapid sequence intubation).

Remember, YOU CAN ALWAYS GIVE MORE, but it is very difficult to take away. Therefore, it is easier to prevent cardiorespiratory depression by being patient and methodical. TITRATE TO EFFECT.

Priorities of Care Related to Analgesia and Sedation

- Keep the casualty alive. DO NOT give analgesia and/or sedation if there are other priorities of care (e.g., hemorrhage control).

- Sustain adequate physiology to maintain perfusion. DO NOT give medications that lower blood pressure or suppress respiration if the patient is in shock or respiratory distress (or is at significant risk of developing either condition).

- Manage pain appropriately (based on the pain categories below).

- Maintain safety. Agitation and anxiety may cause patients to do unwanted things (e.g., remove devices, fight, fall). Sedation may be needed to maintain patient safety and/or operational control of the environment (i.e. in the back of an evacuation platform).

- Stop awareness. During painful procedures, and during some mission requirements, amnesia may be desired. If appropriate, disarm or clear their weapons and prevent access to munitions/ mission essential communications.

General Principles

- Consider pain in three categories:

- Background: the pain that is present because of an injury or wound. This should be managed to keep a patient comfortable at rest but should not impair breathing, circulation, or mental status.

- Breakthrough: the acute pain induced with movement or manipulation. This should be managed as needed. If breakthrough pain occurs often or while at rest, pain medication should be increased in dose or frequency as clinically prudent but within the limits of safety for each medication.

- Procedural: the acute pain associated with a procedure. This should be anticipated and a plan for dealing with it should be considered.

- Analgesia is the alleviation of pain and should be the primary focus of using these medications (treat pain before considering sedation). However, not every patient requires (or should receive) analgesic medication at first, and unstable patients may require other therapies or resuscitation before the administration of pain or sedation medications.

- Sedation is used to relieve agitation or anxiety and, in some cases, induce amnesia. The most common causes of agitation are untreated pain or other serious physiologic problems like hypoxia, hypotension, or hypoglycemia. Sedation is used most commonly to ensure patient safety (e.g., when agitation is not controlled by analgesia and there is need for the patient to remain calm to avoid movement that might cause unintentional tube, line, dressing, splint, or other device removal or to allow a procedure to be performed) or to obtain patient amnesia to an event (e.g., forming no memory of a painful procedure or during paralysis for ventilator management).

- In a Role 1 (or PCC) setting, intravenous (IV) or interosseous (IO) medication delivery is preferred over intramuscular (IM) therapies. The IV/IO route is more predictable in terms of dose-response relationship.

- Each patient responds differently to medications, particularly with respect to dose. Some individuals require substantially more opioid, benzodiazepine, or ketamine; some require significantly less. Once you have a “feel” for how much medication a patient requires, you can be more comfortable giving it to patient with a broad range of injuries.

- Similar amounts during redosing. In general, a single medication will achieve its desired effect if enough is given; however, the higher the dose, the more likely the side effects.

- Additionally, ketamine, opioids, and benzodiazepines given together have a synergistic effect: the effect of medications given together is much greater than a single medication given alone (i.e., the effect is multiplied, not added, so go with less than what you might normally use if each were given alone).

- Pain medications should be given when feasible after injury or as soon as possible after the management of MARCH and appropriately documented (medication administered, dose, route and time). Factors for delayed pain management (other than Combat Pill Pack) are need for individual to maintain a weapon/security and inability to disarm the patient.

- PCC requires a different treatment approach than TCCC. Go slowly, use lower doses of medication, titrate to effect, and re-dose more frequently. This will provide more consistent pain control and sedation. High doses may result in dramatic swings between over sedation with respiratory suppression and hypotension alternating with agitation and emergence phenomenon.

Drips and Infusions

For IV/IO drip medications: Use normal saline to mix medication drips when possible, but other crystalloids (e.g., lactated Ringer’s, Plasmalyte, and so forth) may be used if normal saline is not available. DO NOT mix more than one medication in the same bag of crystalloid. Mixing medications together, even for a relatively short time, may cause changes to the chemical structure of one or both medications and could lead to toxic compounds.

If a continuous drip is selected, use only a ketamine drip in most situations, augmented by push doses of opioid and/or midazolam if needed. Multiple drips are difficult to manage and should only be undertaken with assistance from a Teleconsultation with critical care experience. Multiple drips are most likely to be helpful in patients who remain difficult to sedate with ketamine drip alone and can “smooth out” the sedation (e.g., fewer peaks and troughs of sedation with corresponding deep sedation mixed with periods of acute agitation).

Other medications that should be available when providing narcotic pain control is Naloxone. If the patient receives too much medication, consider dilution of 0.4mg of naloxone in 9ml saline (40mcg/mL) and administer 40mcg IV/IO PRN to increase respiratory rate, but still maintaining pain control.

The PCC Pain Management Guideline Tables

These tables are intended to be a quick reference guide but are not standalone: you must know the information in the rest of the guideline. The tables are arranged according to anticipated clinical conditions, corresponding goals of care, and the capabilities needed to provide effective analgesia and sedation according to the minimum standard, a better option when mission and equipment support (all medics should be trained to this standard), and the best option that may only be available in the event a medic has had additional training, experience, and/or available equipment.

Medications in the table are presented as either give or consider:

- Give: Strongly recommended.

- Consider: Requires a complete assessment of patient condition, environment, risks, benefits, equipment, and provider training.

Use these steps when referencing the tables:

Step 1. Identify the clinical condition

- Standard analgesia is for most patients. The therapies used here are the foundation for pain management during PCC. Expertise in dosing fentanyl (OTFC or IV) and ketamine IV or IO is a must. Intramuscular and intranasal dosing of medications isn’t recommended in a PCC setting.

- Difficult analgesia or sedation needed is for patients in whom standard analgesia does not achieve adequate pain control without suppressing respiratory drive or causing hypotension, OR when mission requirements necessitate sedating a patient to gain control over their actions to achieve patient safety, quietness, or necessary positioning.

- Protected airway with mechanical ventilation is for patients who have a protected airway and are receiving mechanical ventilatory support or are receiving full respiratory support via assisted ventilation (i.e. bag valve).

- Shock present is for patients who have hypotension, active hemorrhage, and/or tachycardia.

Step 2. Read down the column to the row representing your available resources and training.

Step 3. Provide analgesia/sedation medication accordingly.

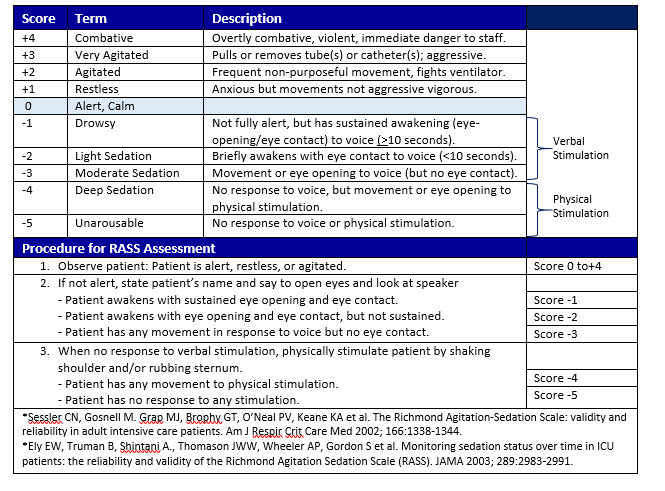

Step 4. Consider using the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) score (Appendix E) as a method to trend the patient’s sedation level.

Special Considerations

Patient Monitoring During Sedation

Patients receiving analgesia and sedation require close monitoring for life-threatening side-effects of medications.

- Minimum: Blood pressure cuff, stethoscope, pulse oximeter; document vital signs trends.

- Better: Capnography in addition to minimum requirements

- Best: Portable monitor providing continuous vital signs display and capnography; document vital signs trends frequently.

Analgesia and Sedation for Expectant Care (i.e. End-of-Life Care)

An unfortunate reality of our profession, both military and medical, is that we encounter clinical scenarios that will inevitably end in a patient’s death. In these situations, it is a healthcare provider’s obligation to give palliative therapy to minimize the person’s suffering. In these circumstances, the use of opioid analgesics and sedative medications is therapeutic and indicated, even if these medications worsen a patient’s vital signs (i.e., cause respiratory depression and/or hypotension). If a patient is expectant:

- Teleconsultation

- Prepare to:

- Give opioid until the patient’s pain is relieved. If the patient is unable to communicate their pain, give opioid medication until the respiratory rate is less than 20/min.

- If the patient complains of feeling anxious (i.e., is worrying about the future but not complaining of pain) or he cannot express himself but is agitated despite having a respiratory rate less than 20/min, give a benzodiazepine until the anxiety is relieved or the patient is sedated (i.e., is not feeling anxious or is no longer agitated).

- Position the patient as comfortably as possible. Pad pressure points.

- Provide anything that gives the patient comfort (e.g., water, food, cigarette).

- Under no circumstances should paralytics be used without analgesia/sedation

*Link to Analgesia and Sedation Management in Prolonged Field Care, 11 May 2017 CPG 15

*Link to Pain, Anxiety and Delirium, 26 April 2021 CPG 16

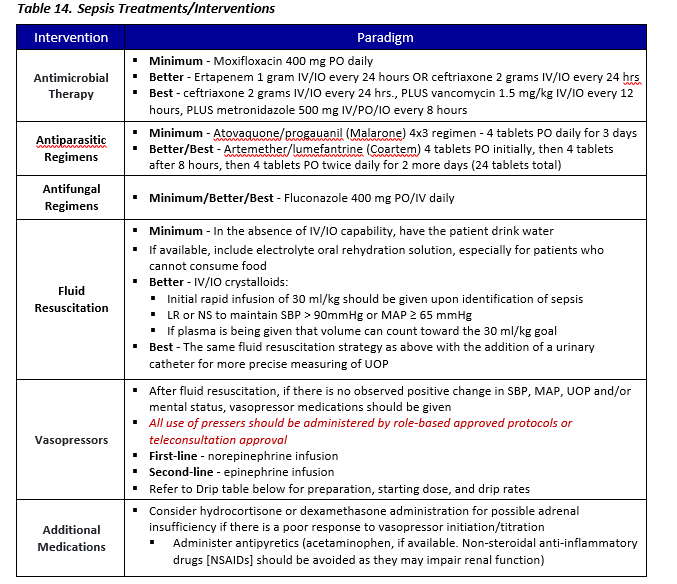

ANTIBIOTICS, SEPSIS, AND OTHER DRUGS - PCC

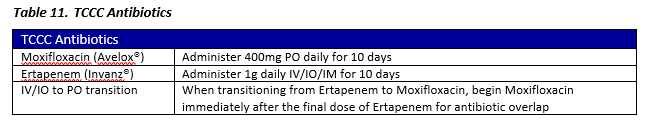

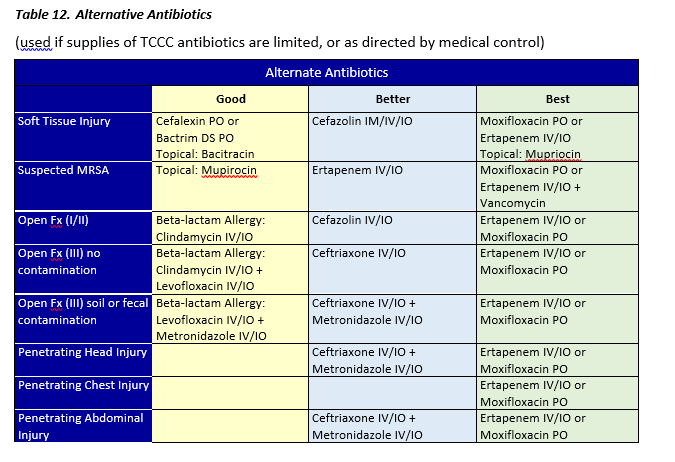

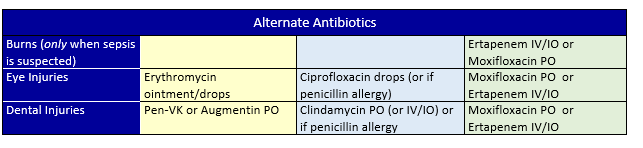

Complete Basic TCCC Management Plan for Antibiotics then:

Antibiotics should be given immediately after injury or as soon as possible after the management of MARCH and Pain Management and appropriately documented (medication administered, dose, route and time).

Confirm that initial TCCC dose of moxifloxacin (Avelox®) or Ertapenem (Invanz®) have already been given for any penetrating trauma. If available, administer tetanus toxoid IM as soon as possible.

Antibiotics should be given daily for seven to 10 days, depending on the type of antibiotic given (see below tables for antibiotics). When able/available, transition IV/IO antibiotics to PO as soon as possible to conserve supplies and equipment.

Sepsis Management

- Blunt or penetrating injuries may cause sepsis in untreated or undertreated patients

- Early recognition of impending sepsis and immediate treatment are imperative to improve changes of survival

- Maintain a high degree of suspicion for signs of early and/or progressing sepsis while performing continuous triage

- Sepsis is defined as suspected or proven infection plus evidence of end organ dysfunction.

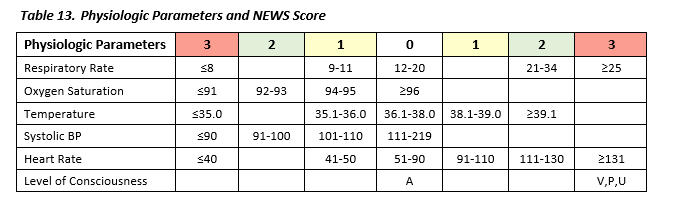

- The National Early Warning Score (NEWS)17 is an aggregate scoring system indicating early physiologic derangements:

- For the purposes of this guideline, a NEWS score of >2 is used to increase the sensitivity for detection of and evaluation for sepsis.

- Early teleconsultations should be used for any signs of sepsis

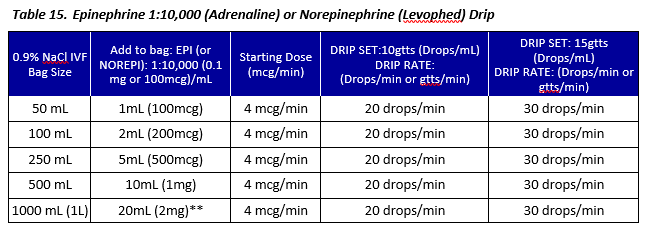

- Additional parenteral antibiotics may be required to treat sepsis as well as vasopressors.

- All use of pressers should be administered by role-based approved protocols or teleconsultation approval.

NOTE: Surgical telemedicine consultation is highly recommended to guide management of intra-abdominal infections (i.e. appendicitis, cholecystitis, diverticulitis, abdominal abscess).

**This is the least recommended approach as it commits a high volume of epinephrine to a large bag. If the patient’s vital signs (BP/MAP/HR) stabilize, the bag must be discontinued and the medic risks wasting some of their resources – “you can mix a drug in an IV bag, but you can’t take it out.”

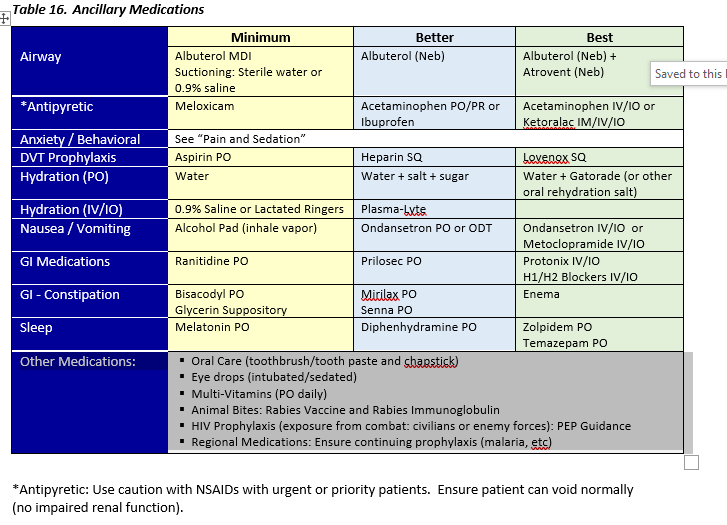

Ancillary Medications

During PCC, additional medications may be required during the extended treatment of casualties, in addition to pain and antibiotic medications. These medications may have synergistic effects to further reduce pain or fever. Some medications may be utilized to treat side-effects of medications, to include nausea or other GI related issues.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis is also recommended for patients that are expected to be in a PCC setting for greater than 48 hours that have achieved hemostasis from wounds or are not at risk for further hemorrhage.

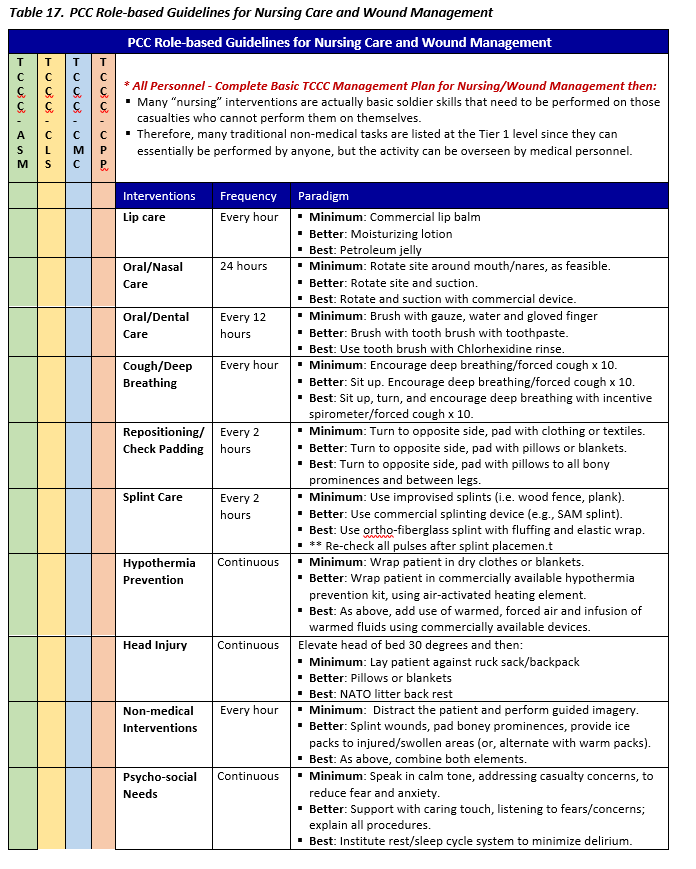

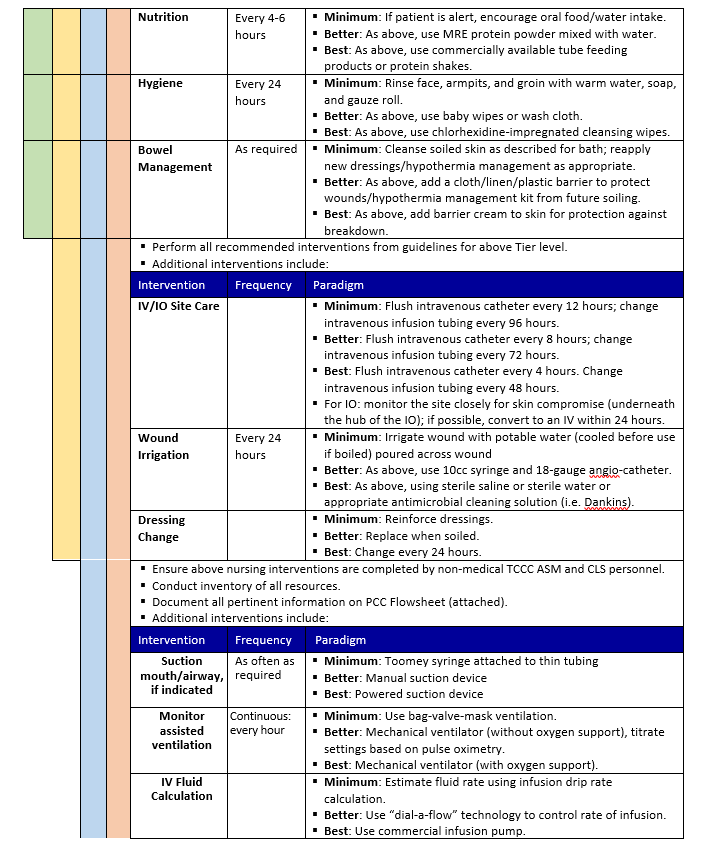

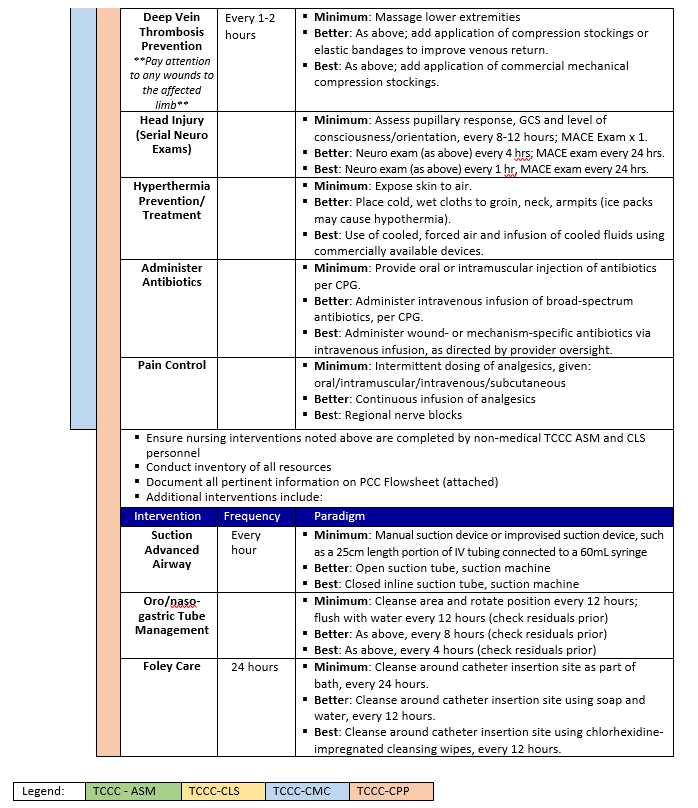

WOUND CARE AND NURSING - PCC

Background

Nursing interventions may not appear important to the medical professionals caring for a patient, but such interventions greatly reduce the possibility of complications such as DVT, pneumonia, pressure sores, wound infection, and urinary tract infection; therefore, essential nursing and wound care should be prioritized in the training environment. Critically ill and injured casualties are at high risk for complications that can lead to adverse outcomes such as increased disability and death. Nursing care is a core principle of PCC to reduce the risk of preventable complications and can be provided without costly or burdensome equipment.20

- Using a nursing care checklist assists with developing a schedule for performing appropriate assessments and interventions.

- Cross training all team members on these interventions prior to deployment will lessen the demand on the medic, especially when caring for more than one patient.

- Prolonged Casualty Care Flowsheets, Nursing Care Checklists, Nursing Care Plans, Assessment/Intervention Packing List, and Recommended Nursing Skill Checklist for Clinical Rotations are included as a PCC Guidelines Appendix. (Also located in JTS Nursing Intervention in Prolonged Field Care CPG, 22 Jul 2018 18).

Pre-deployment, Mission Planning, and Training Considerations

- Hands-on experience is optimal; simulation is a reasonable substitute

- Practice with minimal technology so you are prepared when you lose access to electricity, water

- Regular monitoring, reassessment, and intervention is lifesaving but can be resource-intensive

- Utilize the Recommended Nursing Skill Checklist for Clinical Rotations included in Appendix B to maximize training opportunities.

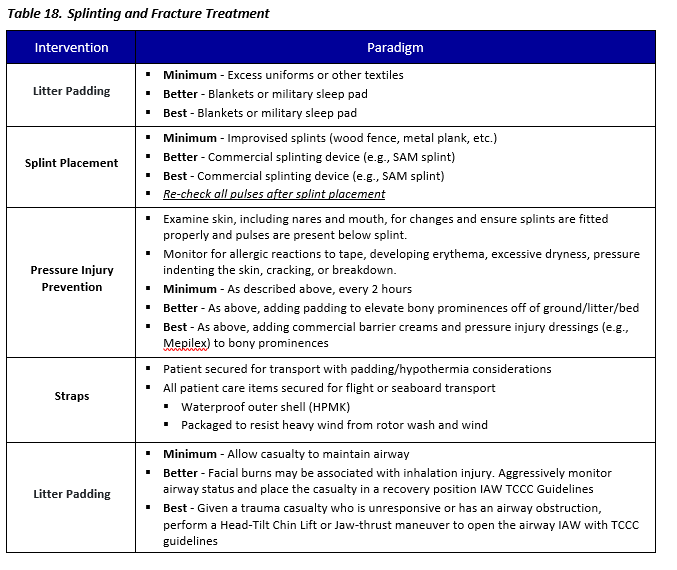

SPLINTING AND FRACTURE MANAGEMENT - PCC

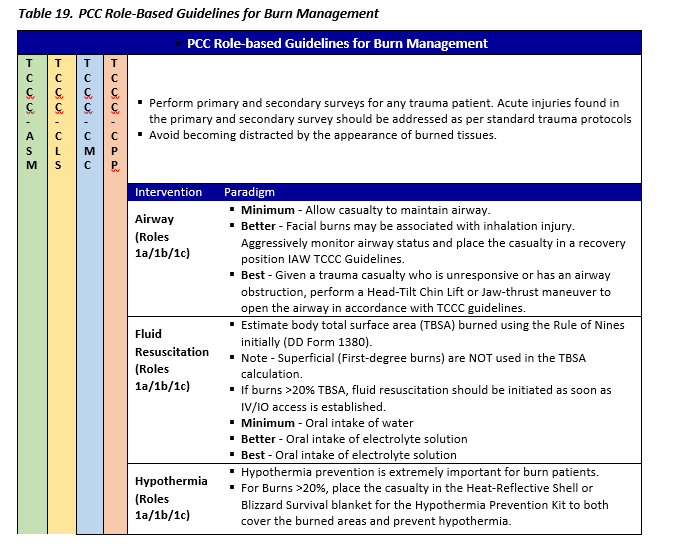

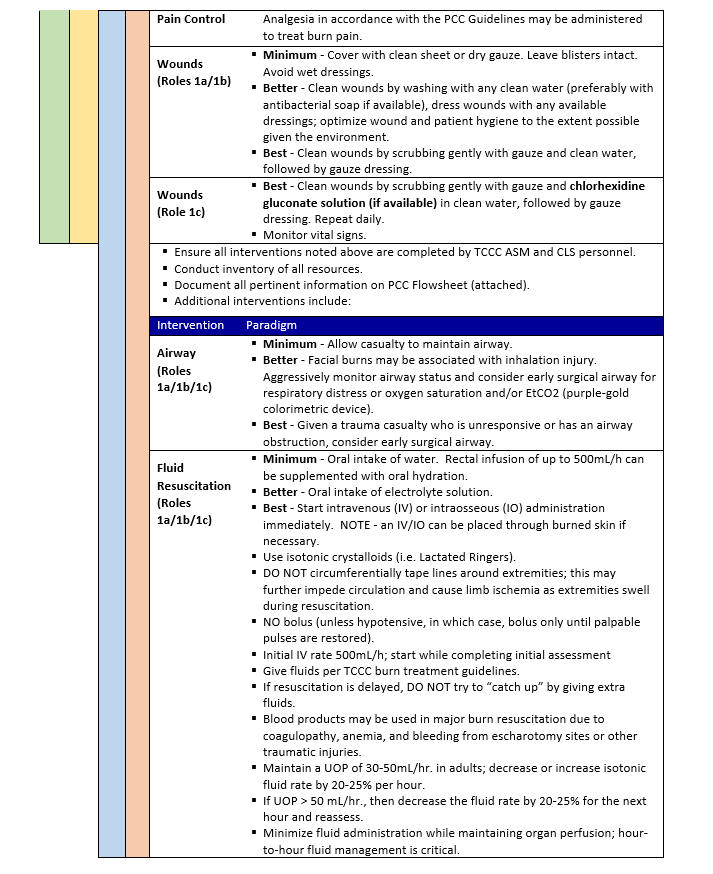

BURN TREATMENT - PCC

Background

- Interrupt the burning process

- Address any life-threatening process based on MARCH assessment as directed by TCCC.

- A burned trauma casualty is a trauma casualty first

- All TCCC skills can be performed through burned tissue

Burn Characteristics

- Superficial burns (1st degree) appear red, do not blister, and blanch readily.

- Partial thickness burns (2nd degree) are moist and sensate, blister, and blanch.

- Full thickness burns (3rd degree) appear leathery, dry, non-blanching, are insensate, and often contain thrombosed vessels

*Link to Burn Wound Management in Prolonged Field Care, 13 Jan 2017 CPG 23

Special Considerations in Burn Injuries

Chemical Burns

NOTE: Refer to the JTS Inhalation Injury and Toxic Industrial Chemical Exposure CPG for additional information.

- Expose body surfaces, brush off dry chemicals, and copiously irrigate with clean water. Large volume (>20L) serial irrigations may be needed to thoroughly cleanse the skin of residual agents. Do not attempt to neutralize any chemicals on the skin.

- Use personal protective equipment to minimize exposure of medical personnel to chemical agents.

- White phosphorous fragments ignite when exposed to air. Clothing may contain white phosphorous residue and should be removed. Fragments embedded in the skin and soft tissue should be irrigated out if possible or kept covered with soaking wet saline dressings or hydrogels.

- Seek early consultation from the USAISR Burn Center (DSN 312-429-2876 (BURN); Commercial (210) 916-2876 or (210) 222-2876; email: usarmy.jbsa.medcom-aisr.list.armyburncenter@health.mil

Electrical Burns

- TCCC ASM and CLS personnel should remove the patient from the electricity source while avoiding injury themselves.

- For cardiac arrest due to arrhythmia after electrical injury, follow advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocol and provide hemodynamic monitoring if spontaneous circulation returns.

- Small skin contact points (cutaneous burns) can hide extensive soft tissue damage.

- Observe the patient closely for clinical signs of compartment syndrome.

- Tissue that is obviously necrotic must be surgically debrided.

NOTE: Escharotomy, which relieves the tourniquet effect of circumferential burns, will not necessarily relieve elevated muscle compartment pressure due to myonecrosis associated with electrical injury; therefore, fasciotomy is usually required.

- Compartment syndrome and muscle injury may lead to rhabdomyolysis, causing pigmenturia and renal injury.

- Pigmenturia typically presents as red-brown urine. In patients with pigmenturia, fluid resuscitation requirements are much higher than those predicted for a similar-sized thermal burn.

- Isotonic fluid infusion should be adjusted to maintain UOP 75-100 mL/hr. in adult patients with pigmenturia.

- If the pigmenturia does not clear after several hours of resuscitation consider IV infusion of mannitol, 12.5 g per liter of lactated Ringer’s solution, and/or sodium bicarbonate (150 mEq/L in D5W). These infusions may be given empirically; it is not necessary to monitor urinary pH. In patients receiving mannitol (an osmotic diuretic), close monitoring of intravascular status via CVP and other parameters is required.

- Seek early consultation from the USAISR Burn Center (DSN 312-429-2876 (BURN); Commercial (210) 916-2876 or (210) 222-2876; email : usarmy.jbsa.medcom-aisr.list.armyburncenter@health.mil

Pediatric Burn Injuries

- Children with acute burns over 15% of the body surface usually require a calculated resuscitation.

- Place a bladder catheter if available (size 6 Fr for infants and 8 Fr for most small children).

- The Modified Brooke formula (3 mL/kg/%TBSA LR or other isotonic fluid divided over 24 hours, with one-half given during the first 8 hours) is a reasonable starting point. This only provides a starting point for resuscitation, which must be adjusted based on UOP and other indicators of organ perfusion. Goal UOP for children is 0.5-1mL/kg/hr.

- Very young children do not have adequate glycogen stores to sustain themselves during resuscitation. Administer a maintenance rate of D5LR to children weighing < 20 kg. Utilize the 4-2-1 rule: 4ml/kg for the first 10kg + 2ml/kg 2nd 10kg + 1ml/kg over 20kg.

- In children with burns > 30% TBSA, early administration may reduce overall resuscitation volume.

- Monitor resuscitation in children, like adults, based on physical examination, input and output measurements, and analysis of laboratory data.

- The well-resuscitated child should have alert sensorium, palpable pulses, and warm distal extremities; urine should be glucose negative.

- Cellulitis is the most common infectious complication and usually presents within 5 days of injury. Prophylactic antibiotics do not diminish this risk and should not be used unless other injuries require antimicrobial coverage (penetrating injury or open fracture).

- Most antistreptococcal antibiotics such as penicillin are successful in eradicating infection. Initial parenteral administration is advised for most children presenting with fever or systemic toxicity.

- Nutrition is critical for pediatric burn patients. Nasogastric feeding may be started immediately at a low rate in hemodynamically stable patients and tolerance monitored. Start with a standard pediatric enteral formula (i.e. Pediasure) targeting 30-35 kcal/kg/day and 2g/kg/day of protein.

- Children may rapidly develop tolerance to analgesics and sedatives; dose escalation is commonly required. Ketamine and propofol are useful procedural adjuncts.

- When burned at a young age, many children will develop disabling contractures. These are often very amenable to correction which may be performed in theater with adequate staff and resources.

- Seek early consultation from the USAISR Burn Center (DSN 312-429-2876 (BURN); Commercial (210) 916-2876 or (210) 222-2876; email burntrauma.consult.army@mail.mil).

- Opportunities for pediatric surgical care provided by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) may be the best option but require the coordinated efforts of the military, host nation, and NGOs.

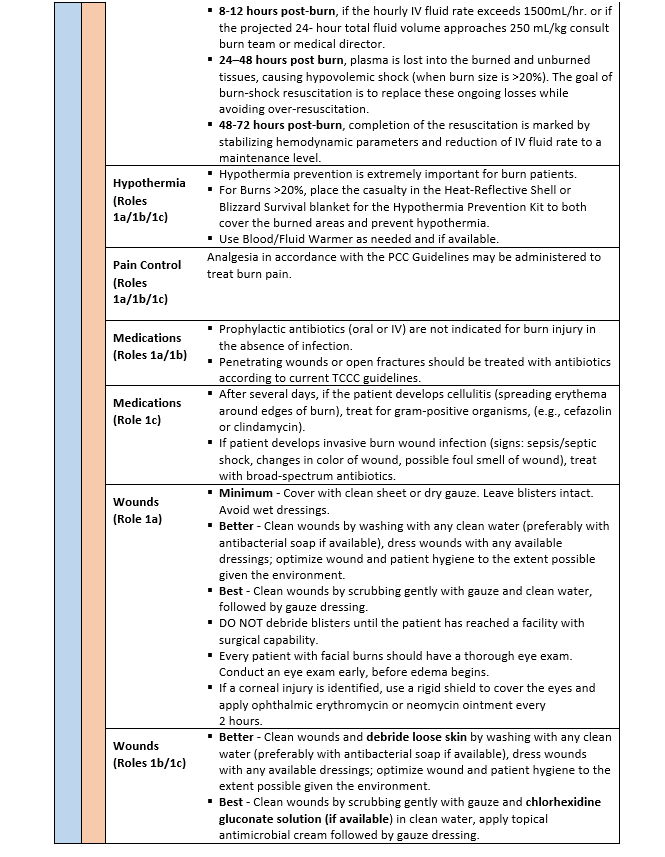

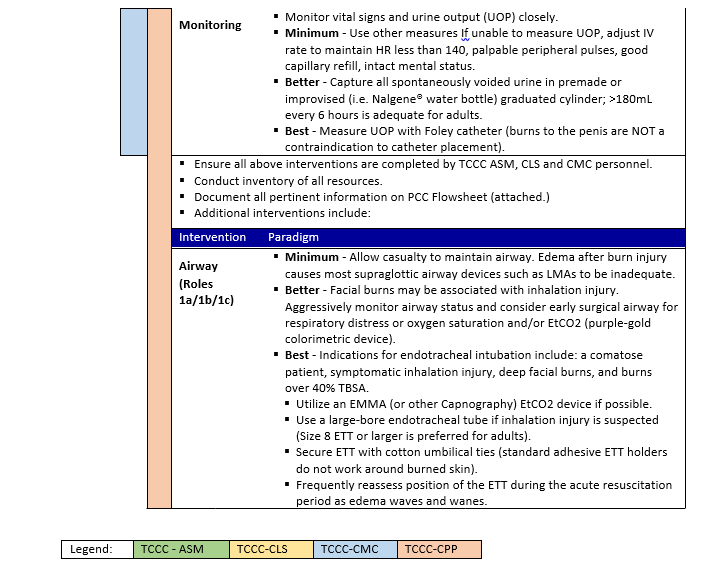

Rule of Nines

On the DD Form 1380 the percentage of coverage on the casualty’s body will need to be documented. The Rule of Nines will help with the estimation. The below figure shows the approximation for each area of the body:

- Eleven areas each have 9% body surface area (head, upper extremities, front and backs of lower extremities, and front and back of the torso having two 9% areas each).

- General guidelines are that the size of the palm of the hand represents approximately 1% of the burned area.

- When estimating, it is easiest to round up to the nearest 10.

- If half of the front or rear area is burned, the area would be half of the area value.

- For example, if half of the front upper/lower extremity is burned, it would be half of 9%, or 4.5%. If half of the front torso is burned, say either the upper or lower part of the front torso, then it would be half of 18%, or 9%.

- Remember, the higher the percentage burned, the higher the chance for hypothermia.

- For children, the percentage of BSA is calculated differently due to the distinctive proportion of major areas.

LOGISTICS - PCC

Background

Reducing the time to required medical or surgical interventions prevents death in potentially survivable illness, injuries and wounds. When evacuation times are extended, en route care (ERC) capability must be adequately expanded to mitigate the delay. In January 2010, the Joint Force Health Protection Joint Patient Movement Report stated “the current success of the medical community is colored by the valiant ability to overcome deficiencies through ‘just-in-time workarounds;’ many systemic shortfalls are resolved and become transparent to patient outcomes. However, future operations may not tolerate current deficiencies.” 24

- Patient packaging is highly dependent upon the transportation or evacuation platform that is available

- If possible, rehearse patient packaging internally and with the external resources.

- Train with all possible assets, familiarizing them with standard operating procedures

- Ensure the patient is stable before initiating a critical patient transfer

REFERENCES

- TCCC Guidelines, 15 Dec 2021.

- Kotwal RS, Howard JT, Orman JA, Tarpey BW, Bailey JA, Champion HR, Mabry RL, Holcomb JB, Gross KR. The effect of a Golden Hour Policy on the morbidity and mortality of combat casualties. JAMA Surg. 2016 Jan;151(1):15-24.

- Kuckelman, J., Derickson, M., Long, W.B. et al. MASCAL Management from Baghdad to Boston: Top Ten Lessons Learned from Modern Military and Civilian MASCAL Events. Curr Trauma Rep 4, 138–148 (2018).

- Gurney JM, Spinella PC. Blood transfusion management in the severely bleeding military patient. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2018;31: 207–214.

- JTS, Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) in Prolonged Field Care, 01 Oct 2018 CPG.

- Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Sequin P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 Suppl 5):S431-7.

- Hudson I, Blackburn MB, Mann-salinas EA, et al. Analysis of casualties that underwent airway management before reaching Role 2 facilities in the Afghanistan conflict 2008-2014. Mil Med. 2020;185(Suppl 1):10-18.

- Blackburn MB, April MD, Brown DJ, et al. Prehospital airway procedures performed in trauma patients by ground forces in Afghanistan. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2018;85(1S Suppl 2):S154-S160.

- JTS, Airway Management in Prolonged Field Care, 01 May 2020 CPG

- JTS, Documentation in Prolonged Field Care, 13 Nov 2018 CPG

- JTS, Documentation Requirements for Combat Casualty Care, 18 Sep 2020 CPG

- JTS, Hypothermia Prevention, Monitoring, and Management, 18 Sep 2012 CPG

- Marr AL, Coronado VG, eds. Central Nervous System Injury Surveillance. Data Submission Standards-2002. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004.

- JTS, Traumatic Brain Injury Management in Prolonged Field Care, 06 Dec 2017 CPG

- JTS, Analgesia and Sedation Management During Prolonged Field Care, 11 May 2017 CPG

- JTS, Pain, Anxiety and Delirium, 26 Apr 2021 CPG

- Keep JW, Messmer AS, Sladden R et al. National Early Warning Score at Emergency Department triage may allow earlier identification of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective observational study. Emerg Med J 2016;33:37–41.

- JTS, Infection Prevention in Combat-Related Injuries, 27 Jan 2021 CPG

- JTS, Sepsis Management in Prolonged Field Care, 28 Oct 2020 CPG

- JTS, Nursing Intervention in Prolonged Field Care, 22 Jul 2018 CPG

- JTS, Acute Traumatic Wound Management in the Prolonged Field Care Setting, 24 Jul 2017 CPG

- JTS Orthopaedic Trauma: Extremity Fractures CPG, 26 Feb 2020

- JTS, Burn Wound Management in Prolonged Field Care, 13 Jan 2017 CPG

- Walrath, B. Searching for systems-based solutions to enhance readiness. Navy Medicine Live online blog.

APPENDIX A: TCCC GUIDELINES

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

APPENDIX B: AIRWAY RESOURCES

Nursing Care Checklist

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

https://prolongedfieldcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/PFC-Nursing-Care-Plan_.pdf

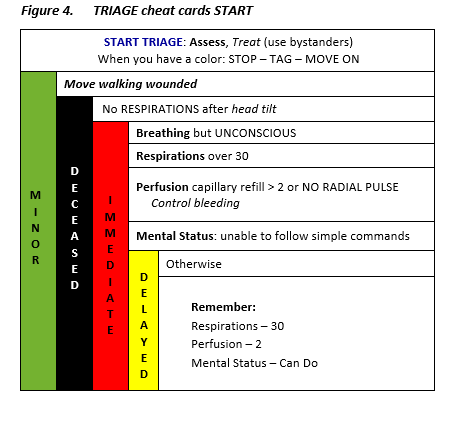

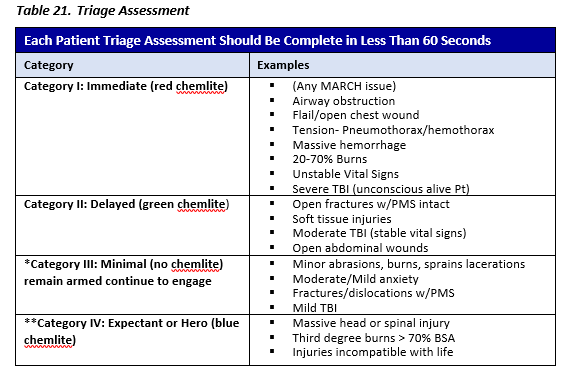

APPENDIX C: MASCAL RESOURCES

Triage Guiding Principles

- Priorities change based on time from injury

- Activities in first hour are CRITICAL

- Don’t waste time with formal triage tools Just extricate/stop threat, stop external bleeding, clear airway

- Transfusion and ventilator support within the first hour identify a resource-intensive patient

- Damage control surgery has little impact after the first hour

* In combat, it is assumed that minimals will continue to stay armed/engaged if no mental status altering pharmaceuticals are given for pain.

**Expectant category is ONLY used in combat operations and/or when the requirements to adequately treat these patients exceed the available resources. In peacetime, it is generally assumed that all patients have a chance of survival. Source: Special Operations Force Medic Handbooks (PJ, Ranger)

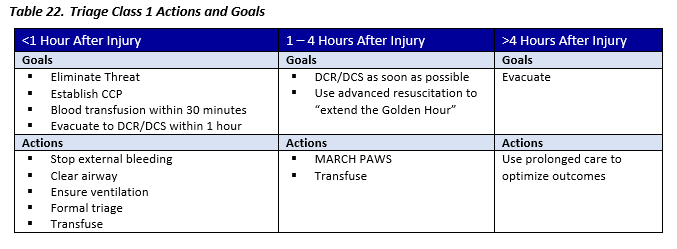

Triage Class 1 (MASCAL)

Adequate medics to treat critical patients and handle the rest

- Many casualties

- Threat controlled

- Resources not severely limited

- Medical personnel can arrive

- Evacuation possible

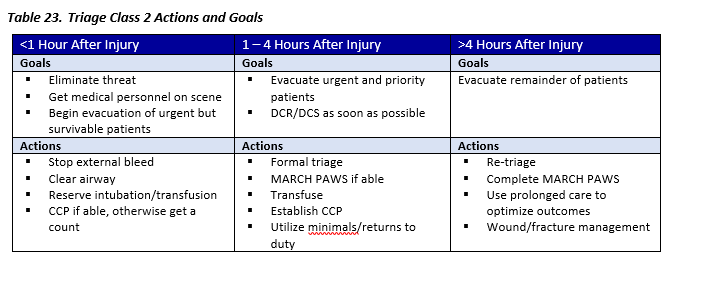

Triage Class 2 (MASCAL)

Unable to manage the number of critical patients

- Numerous casualties or MASCAL (i.e. < 100 Casualties)

- Threat has been controlled or partially controlled

- Resources are very limited

- Medical personnel can arrive (may be delayed > 1 hour)

- Evacuation is possible (may be delayed > 1 hour)

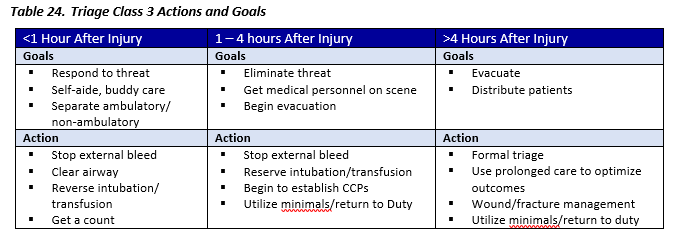

Triage Class 3 (Ultra-MASCAL)

Absolutely overwhelming number of casualties

- Ultra-MASCAL (i.e. >100, possibly thousands of casualties)

- Threat is ongoing

- Resources are severely limited

- Medical personnel unable to arrive in < 1 Hour

- Evacuation not possible in < 1 Hour

MASCAL/Austere Team Resuscitation Record

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/documents/forms_after_action -

Instructions: https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/documents/forms_after_action

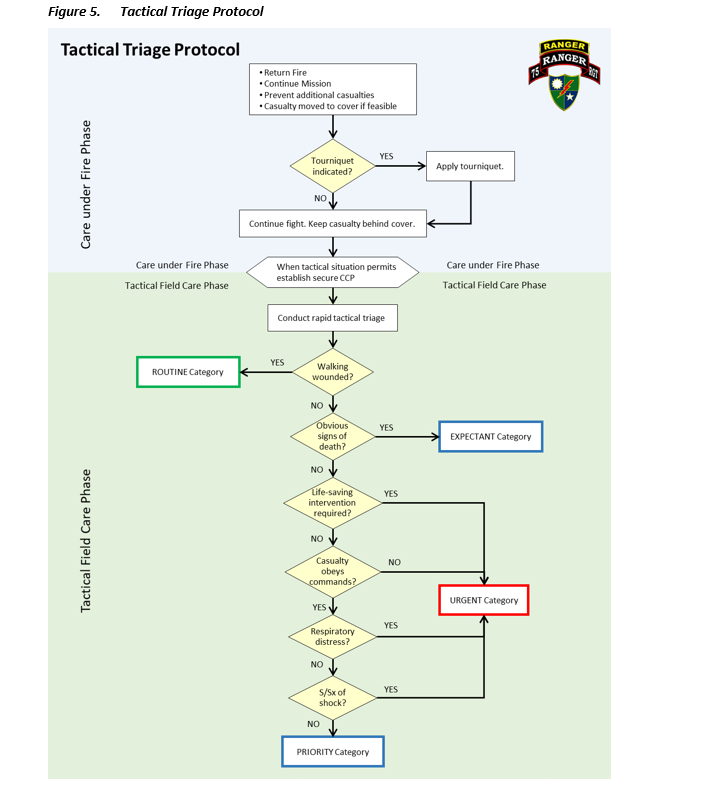

Tactical Triage Protocol (algorithm)

APPENDIX D: DOCUMENTATION RESOURCES

The following resources and associated links are included in this CPG as attachments.

- DD 1380 TCCC Card and accompanying POI TCCC After Action Report

- DD 3019 Resuscitation Record

- DA 4700 TACEVAC form

- Nursing care grid (See Appendix B.)

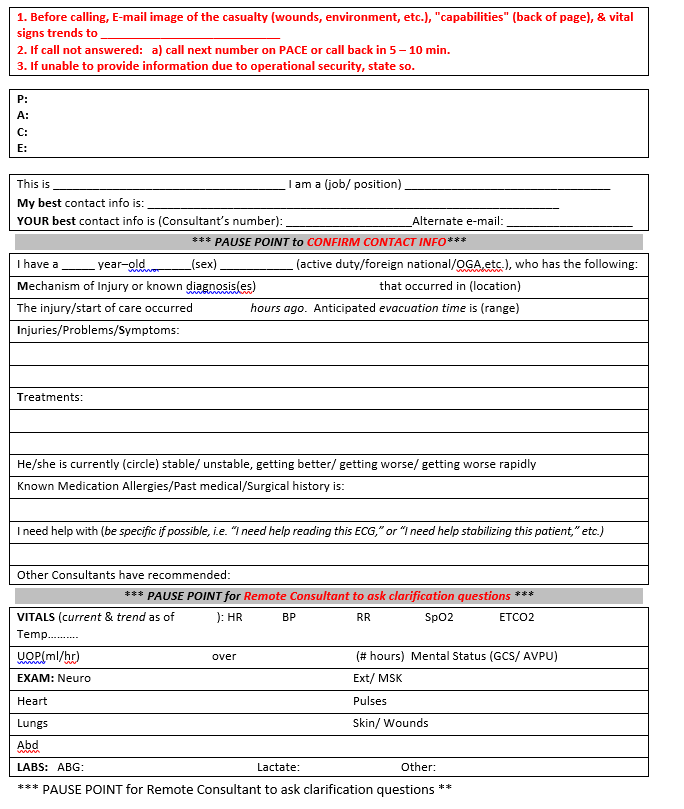

- Teleconsultation Script

DD 1380 TCCC Card

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/documents/forms_after_action

DD 1380 - POI TCCC After Action Report

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/documents/forms_after_action

DD 3019 Resuscitation Record

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/forms/dd/dd3019.pdf

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/documents/forms_after_action -

Instructions: https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/documents/forms_after_action

Prolonged Field Care Casualty Card v22.1, 01 Dec 2020

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

https://jts.health.mil/assests/docs/forms/Prolonged_Field_Care_Casualty_Card-Worksheet.pdf

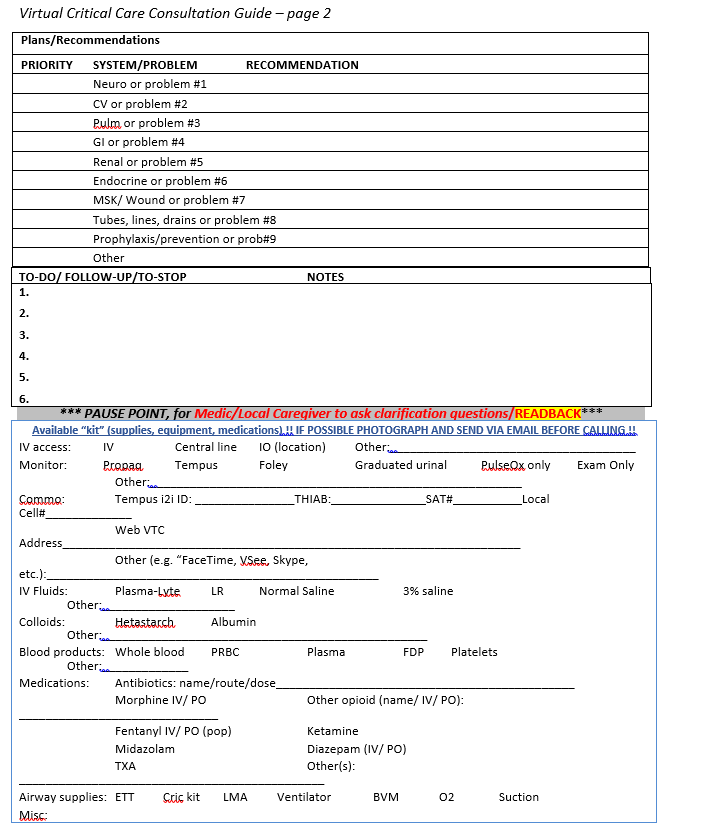

Virtual Critical Care Consultation Guide

Guide is to be used with the Prolonged Field Care Card.

APPENDIX E: TBI RESOURCES

Neurological Examination

MENTAL STATUS

Level of Consciousness: Note whether the patient is:

- Alert/responsive

- Not alert but arouses to verbal stimulation

- Not alert but responds to painful stimulation

- Unresponsive

Orientation: Assess the patient’s ability to provide:

- Name

- Current location

- Current date

- Current situation (e.g., ask the patient what happened to him/her)

Language: Note the fluency and appropriateness of the patient’s response to questions. Note patient’s ability to follow commands when assessing other functions (e.g., smiling, grip strength, wiggling toes). Ask the patient to name a simple object (e.g., thumb, glove, watch).

Speech: Observe for evidence of slurred speech.

CRANIAL NERVES

All patients:

- Assess the pupillary response to light.

- Assess position of the eyes and note any movements (e.g., midline, gaze deviated left or right, nystagmus, eyes move together versus uncoupled movements).

- Noncomatose patient:

- Test sensation to light touch on both sides of the face.

- Ask patient to smile and raise eyebrows, and observe for symmetry.

- Ask the patient to say “Ahhh” and directly observe for symmetric palatal elevation.

- Comatose patient:

- Check corneal reflexes; stimulation should trigger eyelid closure.

- Observe for facial grimacing with painful stimuli.

- Note symmetry and strength.

- Directly stimulate the back of the throat and look for a gag, tearing, and/or cough.

MOTOR

Tone: Note whether resting tone is increased (i.e. spastic or rigid), normal, or decreased (flaccid).

Strength: Observe for spontaneous movement of extremities and note any asymmetry of movement (i.e. patient moves left side more than right side). Lift arms and legs, and note whether the limbs fall immediately, drift, or can be maintained against gravity. Push and pull against the upper and lower extremities and note any resistance given. Note any differences in resistance provided between the left and right sides.

(NOTE: it is often difficult to perform formal strength testing in TBI patients. Unless the patient is awake and cooperative, reliable strength testing is difficult.)

Involuntary movements: Note any involuntary movements (e.g., twitching, tremor, myoclonus) involving the face, arms, legs, or trunk.

SENSORY

If patient is not responsive to voice, test central pain and peripheral pain.

Central pain: Apply a sternal rub or supraorbital pressure, and note the response (e.g., extensor posturing, flexor posturing, localization).

Peripheral pain: Apply nail bed pressure or take muscle between the fingers, compress, and rotate the wrist (do not pinch the skin). Muscle in the axillary region and inner thigh is recommended. Apply similar stimulus to all four limbs and note the response (e.g., extensor posturing, flexor posturing, withdrawal, localization).

NOTE: In an awake and cooperative patient, testing light touch is recommended. It is unnecessary to apply painful stimuli to an awake and cooperative patient.

GAIT

If the patient is able to walk, observe his/her casual gait and note any instability, drift, sway, and so forth.

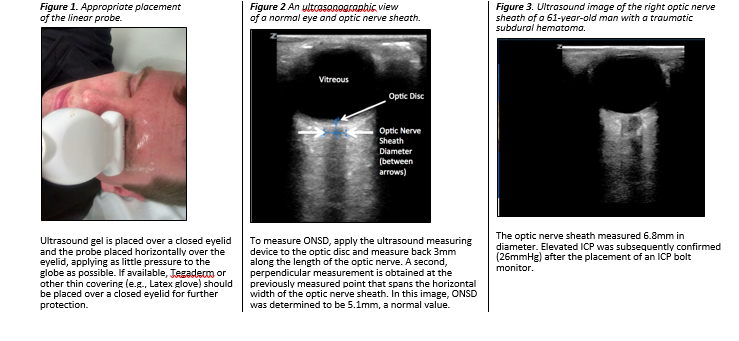

Ultrasonic Assessment of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter

If a patient is unconscious (i.e. does not follow commands or open eyes spontaneously), they may have elevated ICP. There is no reliable test for elevated ICP available outside of a hospital; however, optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) measurement is a rapid, safe, and easy-to-perform ultrasonographic assessment that may help identify elevated ICP when more definitive monitoring devices are not available.

- The optic nerve sheath directly communicates with the intracranial subarachnoid space. Increased ICP, therefore, displaces cerebrospinal fluid along this pathway. Normal ONSD is 4.1–5.9mm.30

- A 10–5-MHz linear ultrasound probe can be used to obtain ONSDs. ONSD is measured from one side of the optic nerve sheath to the other at a distance of 3mm behind the eye immediately below the sclera.31

- In general, ONSDs >5.2mm should raise concern for clinically significant elevations in ICP in unconscious TBI patients.5,32 The ONSD can vary significantly in normal individuals, so one single measurement may not be helpful; however, repeated measurements that detect gradual increases in ONSD over time may be more useful than a single measurement.

- ONSD changes rapidly when the ICP changes, so it can be measured frequently.33 If ONSD is used, it is best to check hourly along with the neurologic examination.

Technique

- Check to make sure there is no eye injury. A penetrating injury to the eyeball is an absolute contraindication to ultrasound because it puts pressure on the eye.

- Ensure the head and neck are in a midline position. Gentle sedation and/or analgesia may be necessary to obtain accurate measurements.

- Ensure the eyelids are closed.

- If available, place a thin, transparent film (e.g., Tegaderm; 3M, http://www.3m.com) over the closed eyelids.

- Apply a small amount of ultrasound gel to closed eyelid.

- Place the 10(–5) MHz linear probe over the eyelid. The probe should be applied in a horizontal orientation (Figure 1) with as little pressure as possible applied to the globe.

- Manipulate the probe until the nerve and nerve sheath are visible at the bottom of screen. An example of a proper ultrasonagraphic image of the optic nerve sheath can be seen in Figure 2.

- Once the optic nerve sheath is visualized, freeze the image on the screen.

- Using the device’s measuring tool, measure 3mm back from the optic disc and then obtain a second measurement perpendicular to the first. The second measurement should cover the horizontal width of the optic nerve sheath (Figure 2). An abnormal ONSD is shown in Figure 3.

- Repeat the previous sequence in the opposite eye. Annotate both ONSDs on the PFC Casualty Card.

- ONSDs should be obtained, when possible, at regular intervals to help assess changes in ICP, particularly when the neurologic examination is poor and/or unreliable (i.e. with sedation). Serial measurements with progressive diameter enlargement and/or asymmetry in ONSDs should be considered indicative of worsening intracranial hypertension.

CAUTION: ONSD measurements are contraindicated in eye injuries. NEVER apply pressure to an injured eye.

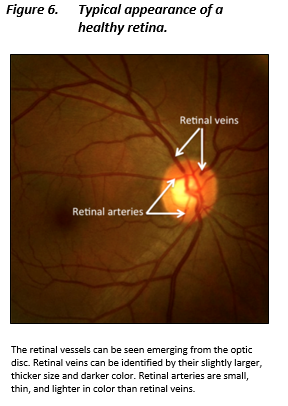

- Spontaneous venous pulsations (SVPs) are subtle, rhythmic variations in retinal vein caliber on the optic disc and have an association with ICP.

- It is difficult to see SVPs without advanced equipment; however, if a handheld ophthalmoscope is available, it is worth an attempt to visualize the retinal veins.

- Don’t worry if you cannot see SVPs; this may actually be normal. However, if you do see them, it is very reassuring that ICP is normal.10

- If SVPs are initially present and can no longer be seen on subsequent examinations, the provider should be concerned for increasing ICP.

- Gently lift the eyelid until the pupil is in view.

- Using a handheld ophthalmoscope, the provider should maneuver himself or herself to a position where the optic disc can be visualized.

- Identify the retinal veins as they emerge from the optic disc. Retinal veins are typically slightly larger and darker than retinal arteries. Figure at right demonstrates the typical appearance of the retina.

- Observe the retinal veins for pulsations. Note the presence or absence of spontaneous venous pulsations

- Repeat the step 1–4 sequence in the contralateral eye.

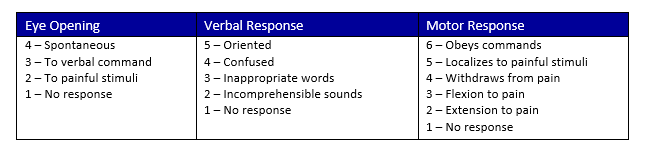

Glasgow Coma Scale

TBI severity classification using the GCS score:

- Mild: 13–15

- Moderate: 9–12

- Severe: 3–8

Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS)

Signs and Symptoms of Elevated Intracranial Pressure

- GCS<8 and suspected TBI

- Rapid decline in mental status

- Fixed dilated pupils(s)

- Cushing’s triad hemodynamics (hypertension, bradycardia, altered respirations)

- Motor posturing (unilateral or bilateral)

- Penetrating brain injury and GCS <15

- Open skull fracture

Hypertonic Saline (HTS) Protocol (goal Na 140-165 meq/L)

- 3% HTS: 250-500 cc bolus, then 50 ml/hr infusion, rebolus as needed for clinical signs

- 5% HTS: decrease above doses by 50%

- 4%: dilute to 3% and use as above. If unable to dilute, can be given as 30 ml bolus and re-dose as needed.

- Central venous line (CVL) preferred for 3% (can be given initially via peripheral IV/IO)

- CVL REQUIRED for 7.5% or higher concentration

Military Acute Concussion Evaluation 2 (MACE 2) Form, 2021

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

MHS Progressive Return to Activity Following Acute Concussion/Mild TBI

Open the attachment on the side menu or open the below link to print or fill out electronically.

APPENDIX F: LOGISTICS RESOURCES

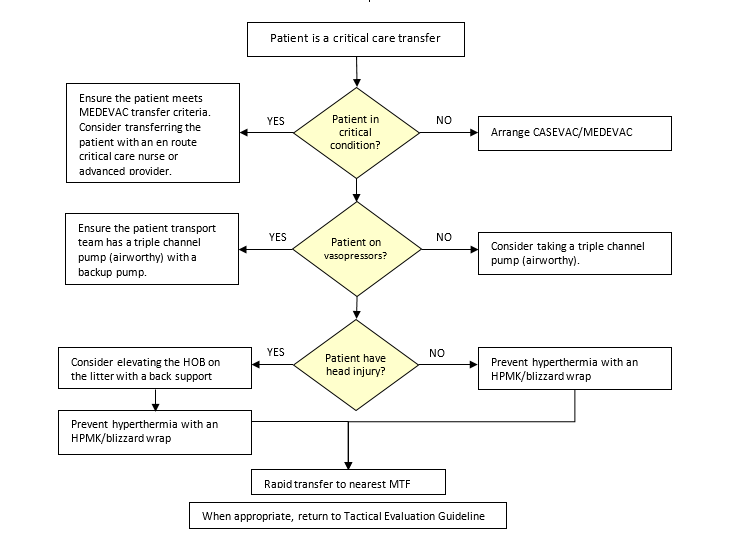

Prolonged Field Care – Patient Packaging, 11 Aug 2021

Patient packaging is highly dependent upon the Casualty Evacuation (CASEVAC) / Medical Evacuation (MEDEVAC) platform that is operationally available. If possible, rehearse patient packaging internally and with the external resources. Train with MEDEVAC assets understand transporting teams’ standard operating procedures in order to best prepare the patient for transport. (Example some teams want to secure the patient and interventions themselves while others may be okay with a fully wrapped patient).

Ensure the patient is stable before initiating a critical patient transfer. For POI/unstable patients ensure the appropriate transport team (MEDEVAC with en route critical care nurse or advanced provider). Interfacility transfers should meet the following minimum:

- Hemorrhage control

- Resuscitation adequate (SBP 70-80 mmHg, MAP >60, or UOP >0.5ml/kg/hr)

- Initial post-op recovery as indicated

- Stabilization of fractures

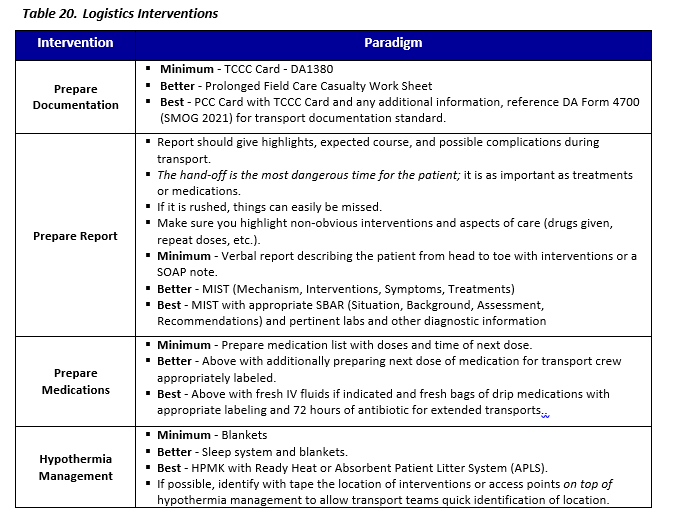

Prepare Documentation

- Good: TCCC Card - DA1380

- Better: Prolonged Field Care Casualty Work Sheet

- Best: PFC Card with TCCC Card and any additional information, reference DA Form 4700 (SMOG 2021) for transport documentation standard

*preference: secure to patient strip of 3in Tape with medications administered attached to blanket or HPMK

Prepare Report

Report should give highlights, expected course, and possible complications during transport. The hand-off is the most dangerous time for the patient it is as important as treatments or medications. If it is rushed things can easily be missed.

- Good: Verbal report describing the patient from head to toe with a SOAP note.

- Best: MIST (Mechanism, Interventions, Symptoms, Treatments)

- Better: MIST with appropriate SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendations) and pertinent labs and other diagnostic information

Prepare Medications

- Good: Prepare medication list with doses and time of next dose

- Better: Above with additionally preparing next dose of medication for transport crew appropriately labeled.

- Best: Above with fresh IV fluids if indicated and fresh bags of drip medications with appropriate labeling and 72 hours of antibiotic for extended transports.

Hypothermia Management

- Good: Blankets

- Better: Sleep system and blankets

- Best: HPMK with Ready Heat or Absorbent Patient Litter System (APLS)

Flight Stressor/ Altitude Management

- Good: Ear Protection and Eye Protection, if nothing available sunglasses and gauze may be used, if patient is sedated and intubated eyes can be taped shut

- Better: Ear Pro and Eye Pro and blankets in all bony areas, Ear Protection and Eye Protection – foamies or actual hearing protection inserts, goggles

- Best: Above with gastric tube (NG/OG) or chest tube for decompression, if indicated. Depending on altitude/platform, consider bleeding air of out bags of fluid.

Secure Interventions and Equipment

- Good: Tape (securely tape all interventions to include IVs, IOs, Airway interventions, Gastric Tubes and TQs). Oxygen tanks should be placed between the patients legs and the monitor should be secured on the oxygen cylinder to prevent injury to the patient. Pumps should be secured to the litter

- Better: Additional litter straps to secure equipment and extend the litter with back support as indicated for vented patients to prevent VAP.

- Best: Above and use the SMEED to keep the monitor and other transport equipment off patient

*if possible, identify with tape the location of interventions or access points on top of hypothermia management to allow transport teams quick identification of location.

Prepare Dressings

Air Evacuation and other MEDEVAC assets do not routinely change dressings during transport; therefore, ensure all dressings are changed, labeled, and secured before patient pick up

- Good: Secure and reinforce dressings with tape, date, and time all dressings.

- Better: Change dressings within 24 hours of departure, secure as above.

- Best: Change and reinforce dressings within 4 hours of departure. Ensure additional Class VIII is available for any unforeseen issues in flight.

Secure the Patient

- Good: Litter with minimum of 2 litter straps

- Better: Litter with padding (example: AE pad or Sleep Mat) with minimum of 3 litter straps

- Best: Litter with padding and flight approved litter headrest with minimum of 3 litter straps (additional litter straps can be used to secure patient or equipment)

Moving a Critical Care Patient

- Good: Two person little carry to CASEVAC/MEDEVAC platform

- Better: Three person little carry on a rickshaw to CASEVAC/MEDEVAC platform

- Best: Four person little carry on a rickshaw to CASEVAC/MEDEVAC platform

Prolonged Casualty Care Patient Packaging Flowchart

Equipment:

- Litter with at least three litter straps

- Three channel IV pump (airworthy)

- Cardiac monitor and cables

- Suction Device

Possible Complications:

- Inadequate medications

- Injuries not addressed before transport

- Inexperienced provider on flight

- Equipment issues

Pearls:

- Document all times – TCCC Card or DA4700.

- Assist Ensure the patient is stable before initiating a critical patient transfer.

- POI/unstable patients ensure the appropriate transport team (MEDEVAC W/ECCN or Advanced provider)

- Interfacility transfers should meet the following minimum:

- Hemorrhage control

- Resuscitation adequate (SBP 70-80 mmHg, MAP >60, or UOP >0.5ml/kg/hr)

- Initial post-op recovery as indicated

- Stabilization of fractures

APPENDIX G: INFORMATION REGARDING OFF-LABEL USES OF FDA-APPROVED PRODUCTS

Purpose

The purpose of this Appendix is to ensure an understanding of DoD policy and practice regarding inclusion in CPGs of “off-label” uses of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products. This applies to off-label uses with patients who are armed forces members.

Background

Unapproved (i.e. “off-label”) uses of FDA-approved products are extremely common in American medicine and are usually not subject to any special regulations. However, under Federal law, in some circumstances, unapproved uses of approved drugs are subject to FDA regulations governing “investigational new drugs.” These circumstances include such uses as part of clinical trials, and in the military context, command required, unapproved uses. Some command requested unapproved uses may also be subject to special regulations.

Additional Information Regarding Off-Label Uses in CPGs

The inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is not a clinical trial, nor is it a command request or requirement. Further, it does not imply that the Military Health System requires that use by DoD health care practitioners or considers it to be the “standard of care.” Rather, the inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is to inform the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner by providing information regarding potential risks and benefits of treatment alternatives. The decision is for the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner within the practitioner-patient relationship.

Additional Procedures

Balanced Discussion

Consistent with this purpose, CPG discussions of off-label uses specifically state that they are uses not approved by the FDA. Further, such discussions are balanced in the presentation of appropriate clinical study data, including any such data that suggest caution in the use of the product and specifically including any FDA-issued warnings.

Quality Assurance Monitoring

With respect to such off-label uses, DoD procedure is to maintain a regular system of quality assurance monitoring of outcomes and known potential adverse events. For this reason, the importance of accurate clinical records is underscored.

Information to Patients

Good clinical practice includes the provision of appropriate information to patients. Each CPG discussing an unusual off-label use will address the issue of information to patients. When practicable, consideration will be given to including in an appendix an appropriate information sheet for distribution to patients, whether before or after use of the product. Information to patients should address in plain language: a) that the use is not approved by the FDA; b) the reasons why a DoD health care practitioner would decide to use the product for this purpose; and c) the potential risks associated with such use.