Module 22: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Tactical Field Care

Joint Trauma System

Module 22: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Tactical Field Care

This module discusses cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) during the Tactical Field Care (TFC) phase.

All Service Members and Combat Lifesaver training does not address the role of CPR. But Combat Medic/Corpsman (CMC) and you, as a Combat Paramedic/Provider (CPP) will need to address any concerns about CPR in Tactical Field Care and apply the TCCC Guidelines.

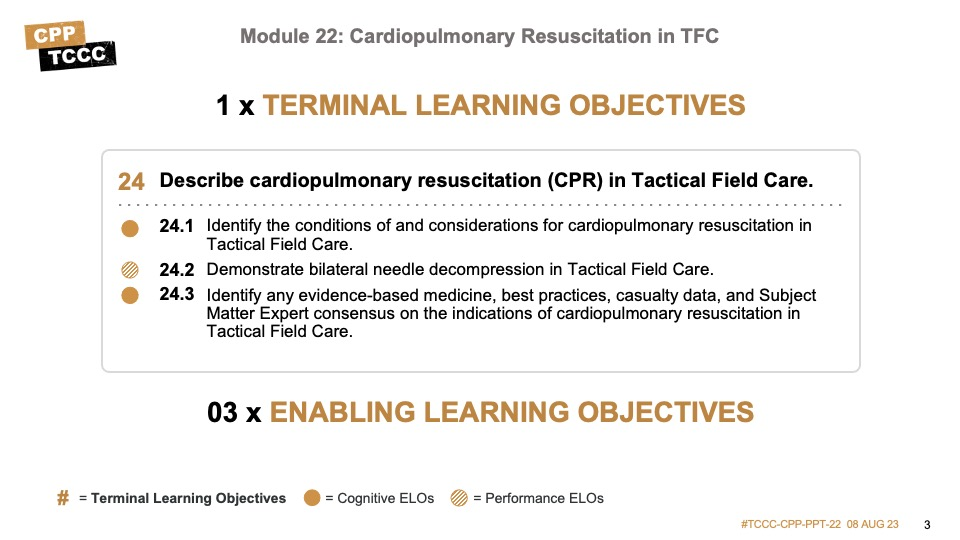

There are two cognitive and one performance-enabling learning objectives for this module.

The cognitive objectives address the identification of the conditions of and considerations for cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Tactical Field Care and the evidence supporting the recommendations.

The performance objective involves demonstrating bilateral needle decompression.

CPR was initially developed to try to maintain perfusion and oxygenation in a casualty with normal blood volume who was in cardiac arrest until defibrillation and advanced cardiac life support measures could be instituted.1 It was never envisioned as a viable treatment for cardiac arrest due to traumatic hypovolemia.

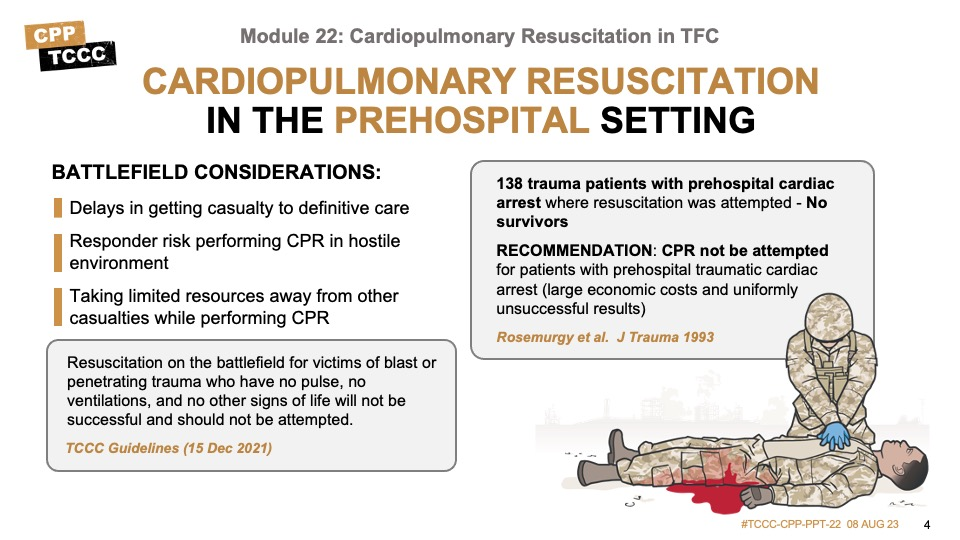

In fact, in civilian prehospital settings, even when a casualty is close to a trauma center, studies have repeatedly emphasized the futility of CPR.2, 3, 4 Many Emergency Medical Systems and professional societies5, 6 recommended that CPR not be attempted for casualties who suffer a prehospital traumatic cardiac arrest, citing the large economic costs7 and the uniformly unsuccessful results. Even in casualties who arrived quickly at a hospital emergency room with a trauma team and underwent a thoracostomy, the survival rate was less than 2%.8

On the battlefield, the delay in getting the casualty to definitive care makes it even less likely that a favorable outcome could be achieved. Dedicating limited resources to resuscitation attempts, or exposing responders to hostile fire while performing CPR, also compounds the situation and risks adversely affecting the outcome of other casualties. This further supports the decision to withhold CPR for casualties on the battlefield.

TCCC Guidelines state:

“Resuscitation on the battlefield for victims of blast or penetrating trauma who have no pulse, no ventilations, and no other signs of life will not be successful and should not be attempted.”9

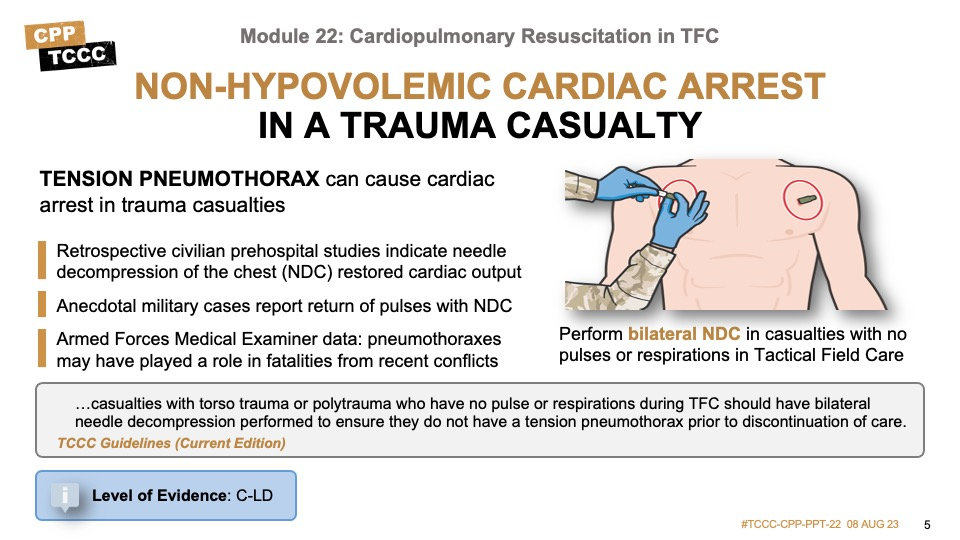

Tension pneumothorax has been identified as a potential cause of non-hypovolemic cardiac arrest in trauma casualties, both in civilian and military research studies and retrospective reviews.10, 11, 12

The data highlighting the improved casualty outcomes with needle decompression of the chest (NDC) is largely centered on casualties who were not in cardiac arrest, but there is some retrospective information to support its utility in pulseless casualties, as well. For example, in one retrospective study of 20,330 advanced life support paramedic calls,12 patients in cardiac arrest were treated with NDC, and three of them had a return of cardiac output.13 And in a study on NDC and thoracotomies in aeromedical evacuations showed that nine out of 26 casualties who were pulseless (34.6%) showed improvement.14

And there are anecdotal examples of success, including a casualty injured during a mounted IED attack in 2011 where the casualty was unconscious from closed head trauma and lost their vital signs during the prehospital phase. When a bilateral needle decompression was done in the emergency room, there was a rush of air from a left-sided tension pneumothorax, and a subsequent return of vital signs.15

The Armed Forces Medical Examiner’s office has also identified undiagnosed tension pneumothoraxes in autopsies of casualties from our recent conflicts.16

Based on this information, several authors and subject matter experts recommend that for combat trauma casualties without a pulse, bilateral NDCs should be performed due to the potential benefit and clear absence of additional harm.17 As a result, the TCCC Guidelines now state:

“…. casualties with torso trauma or polytrauma who have no pulse or respirations during TFC should have bilateral needle decompression performed to ensure they do not have a tension pneumothorax prior to discontinuation of care.”18

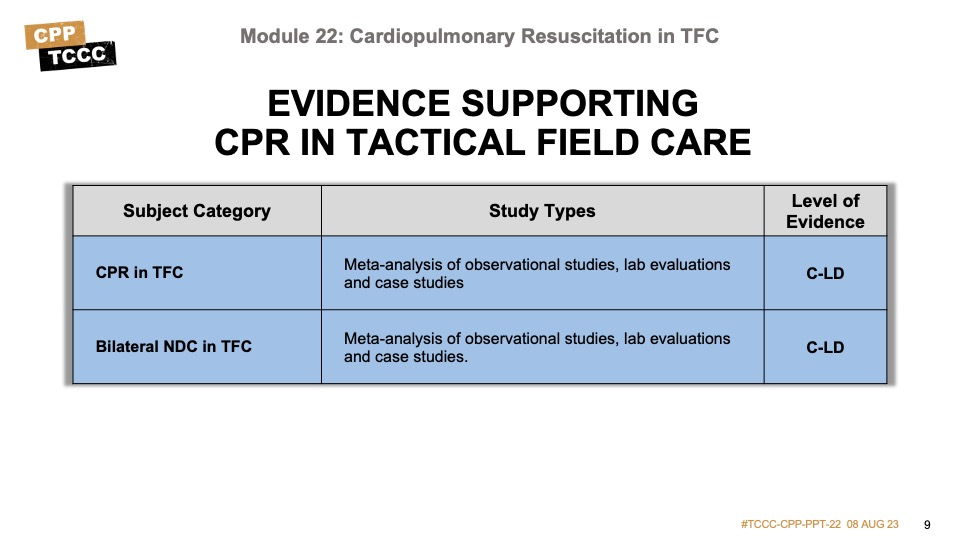

The level of evidence supporting bilateral needle decompression and its use in the tactical environment is based on meta-analysis of observational studies, lab evaluations, and case studies.

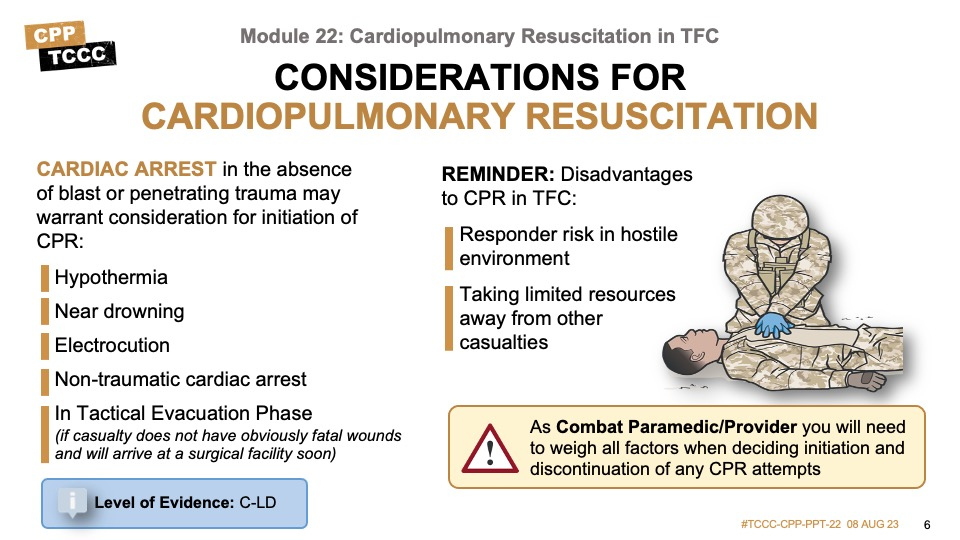

Not all casualties on the battlefield are victims of blast or penetrating trauma. Cardiac arrest in the absence of blast or penetrating trauma may warrant consideration for initiation of CPR.

For example, in severe cases of hypothermia, a casualty can lose vital signs but regain them once they have been actively warmed; and if CPR is initiated, their outcome may be improved. Similarly, near-drowning victims may experience cardiac arrest. Another situation you could encounter is electrocution, in which a return of normal cardiac activity may be delayed but occur even in the absence of defibrillation. These, and other non-traumatic instances of cardiac arrest, may lead you to consider initiating CPR.

However, the same potential drawbacks previously mentioned apply in these cases, as well. If the situation is not safe, the responders may be at risk of becoming casualties while performing CPR. The resources that need to be dedicated to proper CPR are significant, to include multiple people to perform compressions and provide respirations; perhaps over a significant amount of time, depending on the evacuation and transfer options. Mission success should not be compromised, and the Combat Paramedic/Provider will need to weigh all of these issues when making a determination about the initiation and cessation of CPR attempts.

Not covered in depth during this discussion, but important to understand, is that the Tactical Evacuation Phase TCCC Guidelines state:

“CPR may be attempted during this phase of care if the casualty does not have obviously fatal wounds and will be arriving at a facility with a surgical capability within a short period of time. CPR should not be done at the expense of compromising the mission or denying lifesaving care to other casualties.”19

Recommendations for the discontinuation of CPR have not been outlined in TCCC Guidelines or military clinical practice guidance, but several of the principles that guide discontinuation in the civilian prehospital environment can be applied to the tactical setting. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) guidance indicates the termination of resuscitation efforts may be considered when there are no signs of life and there is no return of spontaneous circulation despite appropriate field EMS treatment that includes minimally interrupted CPR.20

The evidence supporting cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the tactical setting has not been well-studied. Nevertheless, the level of evidence supporting its use is based on meta-analysis of observational studies, lab evaluations, and case studies.

Bilateral NDCs are performed using the same techniques you learned for the treatment of tension pneumothorax in the module on respiration.

The following video will demonstrate needle decompression of the chest again.

BILATERAL NEEDLE DECOMPRESSION OF THE CHEST

The following skill card will demonstrate bilateral needle decompression of the chest as a treatment for a casualty with no pulses or respirations in the TFC phase.

The majority of the studies done examining the use of CPR in the prehospital and combat setting have been retrospective reviews of clinical data. The majority of the published data with dismal survival rates is dated, some being 15-20 years old. Newer studies have been accomplished but with smaller sample sizes and potential confounding variables that cast questions about their reproducibility of slightly better outcomes.

As a result, the consensus guidelines from the joint ACS-National Association of Emergency Physicians have not been updated since 2013, and the TCCC Guidelines have not undergone any recent revisions. In the absence of clear data examining the benefits of CPR in this population, the overall level of evidence for withholding CPR relies on those retrospective studies and subject matter consensus opinions, and would be considered low to moderate.

However, the data supporting the benefits of bilateral NDC for the pulseless casualty in a TFC environment is more robust. Most of the studies are still retrospective, and several of the reports are anecdotal and not part of any larger study, but the data demonstrating improved casualty outcomes is greater. As a result, the overall level of evidence to support bilateral NDC in the tactical setting is moderate.

Evidence-based recommendations and guidance are the result of a careful review of studies and discussion by a panel of subject matter experts. For TCCC, the subject matter expert panels include both Committee on TCCC members and select invited subject matter experts from within both the military and civilian community, based on the specific interest area.

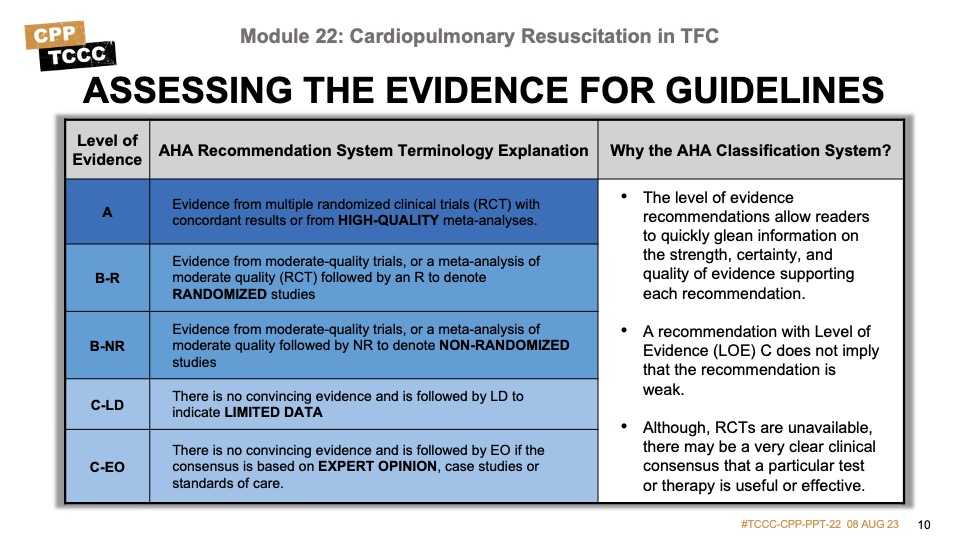

Why the AHA Classification System?

The level of evidence classification combines an objective description of the existence and the types of studies supporting the recommendation and expert consensus, according to 1 of the following 3 categories:35

- Level of evidence A: recommendation based on evidence from multiple randomized trials or meta-analyses

- Level of evidence B: recommendation based on evidence from a single randomized trial or nonrandomized studies

- Level of evidence C: recommendation based on expert opinion, case studies, or standards of care.

The level of evidence recommendations allows readers to quickly glean information on the strength, certainty, and quality of evidence supporting each recommendation. The Level of Evidence (LOE) denotes the confidence in or certainty of the evidence supporting the recommendation, based on the type, size, quality, and consistency of pertinent research findings.36

A recommendation with level of evidence C does not imply that the recommendation is weak. Many important clinical questions addressed in guidelines do not lend themselves to clinical trials. Although, Randomized Clinical Trials are unavailable, there may be a very clear clinical consensus that a particular test or therapy is useful or effective.

During this module, we went over cardiopulmonary resuscitation in TFC.

We highlighted that CPR should not be initiated for a casualty who suffers blast or penetrating trauma with no pulse, respirations, or signs of life. Casualties with torso trauma or polytrauma who have no pulse, or respirations should have bilateral needle decompression performed. And in some non-traumatic conditions, CPR should be considered.

The skill station reinforced the procedures for performing a bilateral needle decompression of the chest.

To close out this module, check your learning with the questions below (answers under the image).

Answers

Should you initiate CPR for a casualty with blast or penetrating trauma who has no pulse, respirations, or signs of life?

- Resuscitation on the battlefield for victims of blast or penetrating trauma who have no pulse, no ventilations, and no other signs of life will not be successful and should not be attempted.

When should you perform a bilateral needle decompression of the chest?

- Casualties with torso trauma or polytrauma who have no pulse or respirations during TFC should have bilateral needle decompression performed to ensure they do not have a tension pneumothorax.

In what circumstance might you consider CPR in the Tactical Field Care phase?

- In severe cases of hypothermia, near-drowning victims, electrocution, or other non-traumatic instances of cardiac arrest.

1 Prehospital Trauma Life Support, Military 9th Edition, 15 Oct 2019, page 830.

2 Powell DW, Moore EE, Cothren CC, Ciesla DJ, Burch JM, Moore JB, Johnson JL. Is emergency department resuscitative thoracotomy futile care for the critically injured patient requiring prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation? J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Aug;199(2):211-5.

3 Stockinger ZT, McSwain NE Jr. Additional evidence in support of withholding or terminating cardiopulmonary resuscitation for trauma patients in the field. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Feb;198(2):227-31.

4 Chinn M, Colella MR. Trauma Resuscitation: An evidence-based review of prehospital traumatic cardiac arrest. JEMS. 2017 Apr;42(4):26-32.

5 Millin MG, Galvagno SM, Khandker SR, Malki A, Bulger EM; Standards and Clinical Practice Committee of the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP); Subcommittee on Emergency Services–Prehospital of the American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma (ACSCOT). Withholding and termination of resuscitation of adult cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to trauma: resource document to the joint NAEMSP-ACSCOT position statements. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Sep;75(3): 459-67.

6 National Association of EMS Physicians and American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (2013) Withholding of Resuscitation for Adult Traumatic Cardiopulmonary Arrest, Prehospital Emergency Care, 17:2, 291

7 Rosemurgy AS, Norris PA, Olson SM, Hurst JM, Albrink MH. Prehospital traumatic cardiac arrest: the cost of futility. J Trauma. 1993 Sep;35(3): 468-73; discussion 473-4.

8 Branney SW, Moore EE, Feldhaus KM, Wolfe RE. Critical analysis of two decades of experience with postinjury emergency department thoracotomy in a regional trauma center. J Trauma. 1998 Jul;45(1): 87-94; discussion 94-5.

9 Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 December 2021, para 16. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 16 Dec 21.

10 Smith JE, Rickard A, Wise D. Traumatic cardiac arrest. J R Soc Med. 2015;108(1): 11-16.

11 Part 10.7: Cardiac Arrest Associated With Trauma. Circulation. 2005;112: 146-149.

12 Barnard EBG, Hunt PAF, Lewis PEH, Smith JE. The outcome of patients in traumatic cardiac arrest presenting to deployed military medical treatment facilities: data from the UK Joint Theatre Trauma Registry. J R Army Med Corps. 2018 Jul;164(3): 150-154.

13 Warner KJ, Copass MK, Bulger EM. Paramedic use of needle thoracostomy in the prehospital environment. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008 Apr-Jun;12(2): 162-8.

14 Davis DP, Pettit K, Rom CD, Poste JC, Sise MJ, Hoyt DB, Vilke GM. The safety and efficacy of prehospital needle and tube thoracostomy by aeromedical personnel. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005 Apr-Jun;9(2): 191-7.

15 Butler FK Jr, et al. Management of Suspected Tension Pneumothorax in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 17-02. J Spec Oper Med. 2018 Summer;18(2):19-35.

16 Butler FK Jr, et al. Management of Suspected Tension Pneumothorax in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 17-02. J Spec Oper Med. 2018 Summer;18(2):19-35.

17 Tien HC, Jung V, Rizoli SB, Acharya SV, MacDonald JC. An evaluation of tactical combat casualty care interventions in a combat environment. J Spec Oper Med. 2009 Winter;9(1): 65-8.

18 Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 December 2021, para 16. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 16 Dec 21.

19 Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 December 2021, Basic Management Plan for Tactical Evacuation Care, para 16.b. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 6 Dec 21.

20 National Association of EMS Physicians and American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (2013) Withholding of Resuscitation for Adult Traumatic Cardiopulmonary Arrest, Prehospital Emergency Care, 17:2, 291.

21 Barnard EBG, Hunt PAF, Lewis PEH, Smith JE. The outcome of patients in traumatic cardiac arrest presenting to deployed military medical treatment facilities: data from the UK Joint Theatre Trauma Registry. J R Army Med Corps. 2018 Jul;164(3): 150-154 C-LD

22 Branney SW, Moore EE, Feldhaus KM, Wolfe RE. Critical analysis of two decades of experience with postinjury emergency department thoracotomy in a regional trauma center. J Trauma. 1998 Jul;45(1): 87-94; discussion 94-5 C-LD

23 Butler FK Jr, et al. Management of Suspected Tension Pneumothorax in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 17-02. J Spec Oper Med. 2018 Summer;18(2):19-35 C-LD

24 Chinn M, Colella MR. Trauma Resuscitation: An evidence-based review of prehospital traumatic cardiac arrest. JEMS. 2017 Apr;42(4):26-32 B-NR

25 Davis DP, Pettit K, Rom CD, Poste JC, Sise MJ, Hoyt DB, Vilke GM. The safety and efficacy of prehospital needle and tube thoracostomy by aeromedical personnel. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005 Apr-Jun;9(2): 191-7 C-LD

26 Millin MG, Galvagno SM, Khandker SR, Malki A, Bulger EM; Standards and Clinical Practice Committee of the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP); Subcommittee on Emergency Services–Prehospital of the American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma (ACSCOT). Withholding and termination of resuscitation of adult cardiopulmonary arrest secondary to trauma: resource document to the joint NAEMSP-ACSCOT position statements. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Sep;75(3): 459-67 C-LD

27 National Association of EMS Physicians and American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (2013) Withholding of Resuscitation for Adult Traumatic Cardiopulmonary Arrest, Prehospital Emergency Care, 17:2, 291 C-LD

28 Part 10.7: Cardiac Arrest Associated With Trauma. Circulation. 2005;112: 146-149 C-LD

29 Po well DW, Moore EE, Cothren CC, Ciesla DJ, Burch JM, Moore JB, Johnson JL. Is emergency department resuscitative thoracotomy futile care for the critically injured patient requiring prehospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation? J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Aug;199(2):211-5 C-LD

30 Rosemurgy AS, Norris PA, Olson SM, Hurst JM, Albrink MH. Prehospital traumatic cardiac arrest: the cost of futility. J Trauma. 1993 Sep;35(3): 468-73; discussion 473-4. C-LD

31 Smith JE, Rickard A, Wise D. Traumatic cardiac arrest. J R Soc Med. 2015;108(1): 11-16 C-LD

32 Stockinger ZT, McSwain NE Jr. Additional evidence in support of withholding or terminating cardiopulmonary resuscitation for trauma patients in the field. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 Feb;198(2):227-31 C-LD

33 Tien HC, Jung V, Rizoli SB, Acharya SV, MacDonald JC. An evaluation of tactical combat casualty care interventions in a combat environment. J Spec Oper Med. 2009 Winter;9(1): 65-8 B-R

34 Warner KJ, Copass MK, Bulger EM. Paramedic use of needle thoracostomy in the prehospital environment. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008 Apr-Jun;12(2): 162-8 C-LD

35 Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith Jr SC. Scientific Evidence Underlying the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Medical Association. 2009 Feb; Vol 301, No. 8.

36 Halparin, JL. Further Evolution of the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendation Classification System. American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. 2016 Apr; 133:1426-1428.