Module 6: Massive Hemorrhage Control

Joint Trauma System

Module 6: Massive Hemorrhage Control

During this module, we will introduce the techniques for identifying and controlling massive hemorrhage. The practical application of this information and the techniques in the form of skills stations and trauma lanes will take place throughout the remainder of the course and will be evaluated at the end of the course during your final assessment.

As Combat Paramedics/Providers (CPP), you are often one of the first lines of medical providers to receive the casualty and initiate more advanced treatments. It is important that you also understand the roles and capabilities of the nonmedical personnel that may be providing care/assisting in care in the prehospital environment.

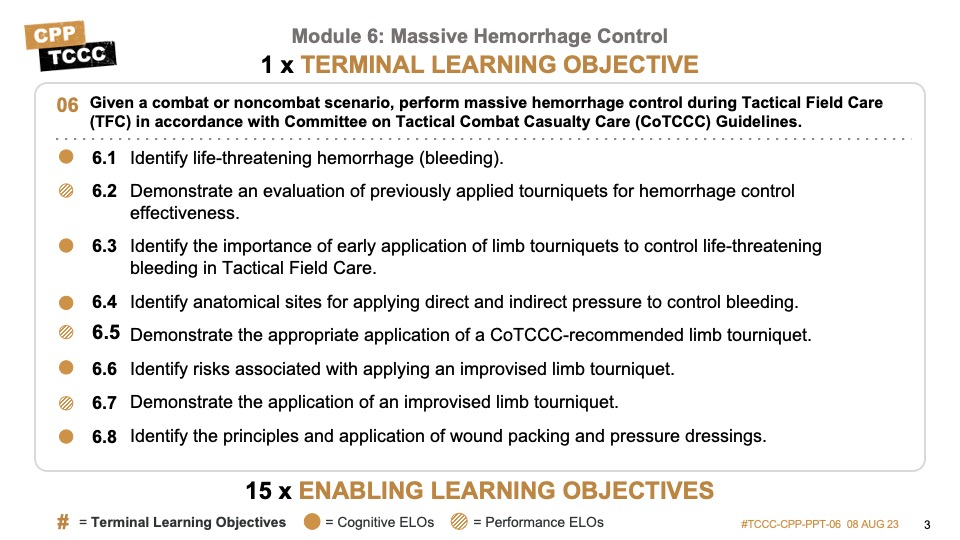

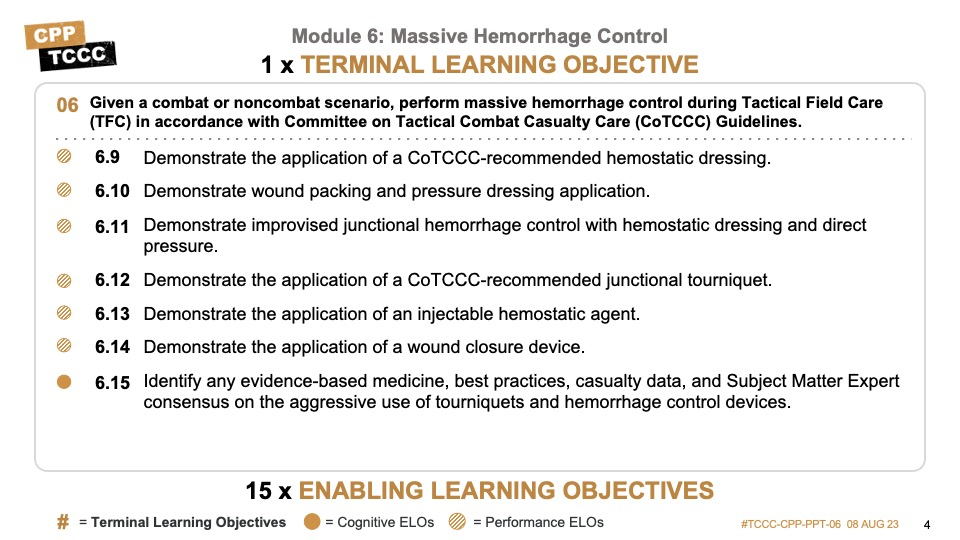

There are six cognitive and nine performance learning objectives for the Massive Hemorrhage Control module.

The cognitive learning objectives are to identify life-threatening hemorrhage (bleeding), identify the importance of early application of limb tourniquets to control life-threatening bleeding, identify anatomical sites for applying direct and indirect pressure to control bleeding, identify risks associated with applying an improvised limb tourniquet, and identify the principles of wound packing. Additionally, we will review the evidence supporting the aggressive use of tourniquets and hemorrhage control devices.

The performance learning objectives are to demonstrate the evaluation of previously applied tourniquets for hemorrhage control effectiveness, the appropriate application of a Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care- (CoTCCC-) recommended limb tourniquet, the application of an improvised limb tourniquet, the application of a CoTCCC-recommended hemostatic dressing, wound packing and application of a pressure bandage, improvised junctional hemorrhage control, the application of a CoTCCC-recommended junctional tourniquet, the application of an injectable hemostatic agent, and the application of a wound closure device.

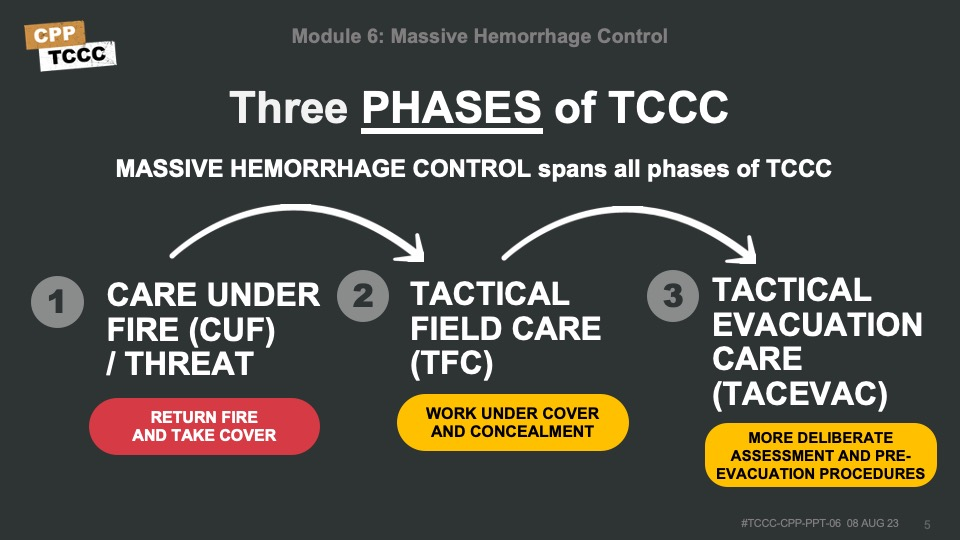

Massive hemorrhage should be identified and controlled as early as possible. It is typically addressed in Care Under Fire (CUF) with limb tourniquets and in Tactical Field Care (TFC) with the additional techniques that you will learn in this module. That said, the casualty and any interventions should be continually reassessed throughout the phases of care and may require you to stop and take action to ensure hemorrhage is controlled throughout your assessment.

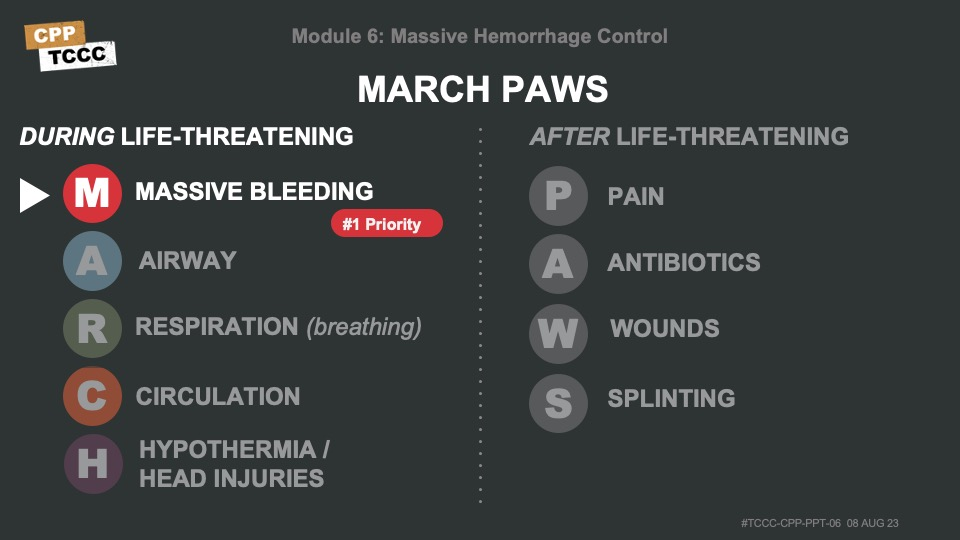

It is critical to be able to quickly identify life-threatening hemorrhage and promptly intervene in accordance with the CoTCCC guidelines. In Care Under Fire, this typically means a quick survey for obvious life-threatening hemorrhage and the application of a high and tight limb tourniquet. The relative safety and security and the additional time afforded in the Tactical Field Care phase allow for a more deliberate approach to assessment and treatment for the M in MARCH PAWS, which is Massive Bleeding and the #1 treatment priority.

The following video provides an overview of the approach to assessment and treatment of massive hemorrhage in Tactical Field Care.

MASSIVE HEMORRHAGE OVERVIEW IN TFC

Since massive hemorrhage control often represents the transition from Care Under Fire to Tactical Field Care (TFC); there are a few things to highlight prior to talking about the details of massive hemorrhage.

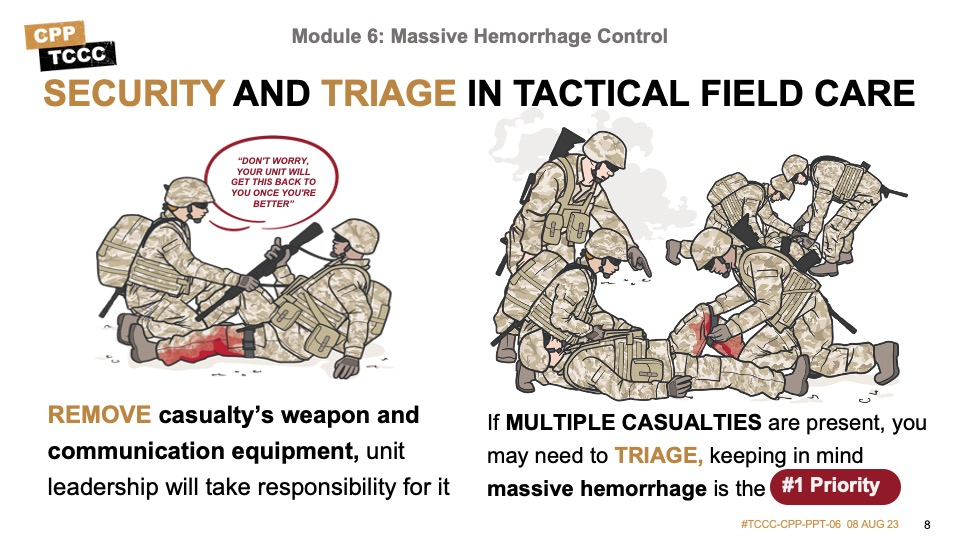

Remember to maintain security and tactical situational awareness during TFC. Casualties with altered mental status who can no longer fight effectively should have weapons, communications equipment, and sensitive items secured so they do not cause harm to themselves, teammates, or the mission.

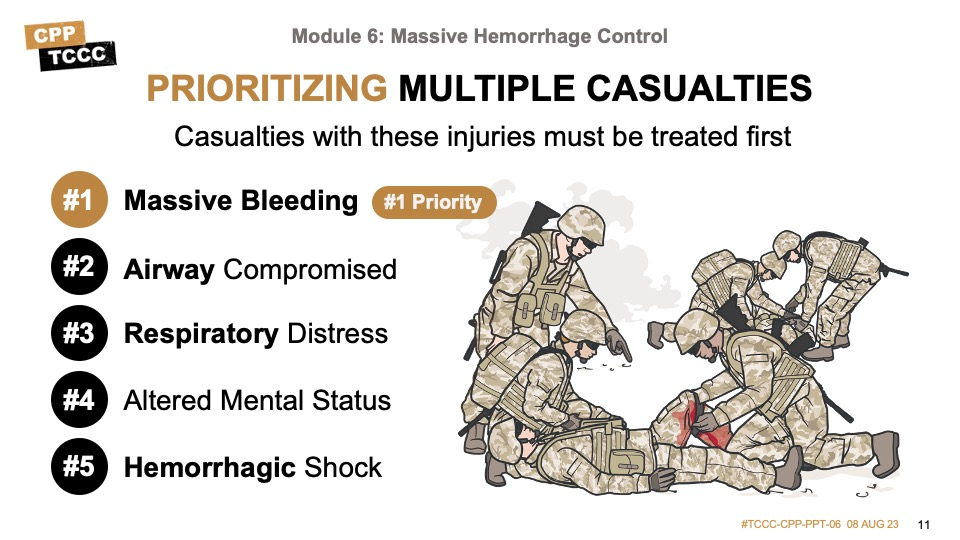

As mentioned previously, it may be necessary to triage casualties and direct the actions of other responders before actually beginning individual casualty assessment while still ensuring that massive bleeding is the #1 treatment priority.

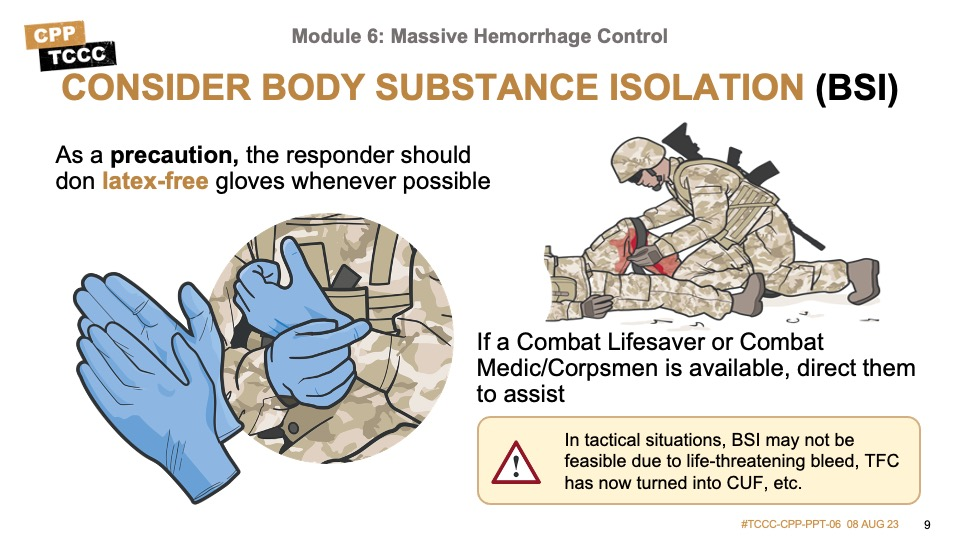

Body substance isolation (or BSI) is a situation-dependent consideration in TCCC. In Care Under Fire there is seldom time to worry about body substance isolation, however in Tactical Field Care, whenever possible, responders should don latex-free gloves as a BSI precaution. Gloves are found in most equipment kits, including the JFAK, CLS bags, and combat medic aid bags.

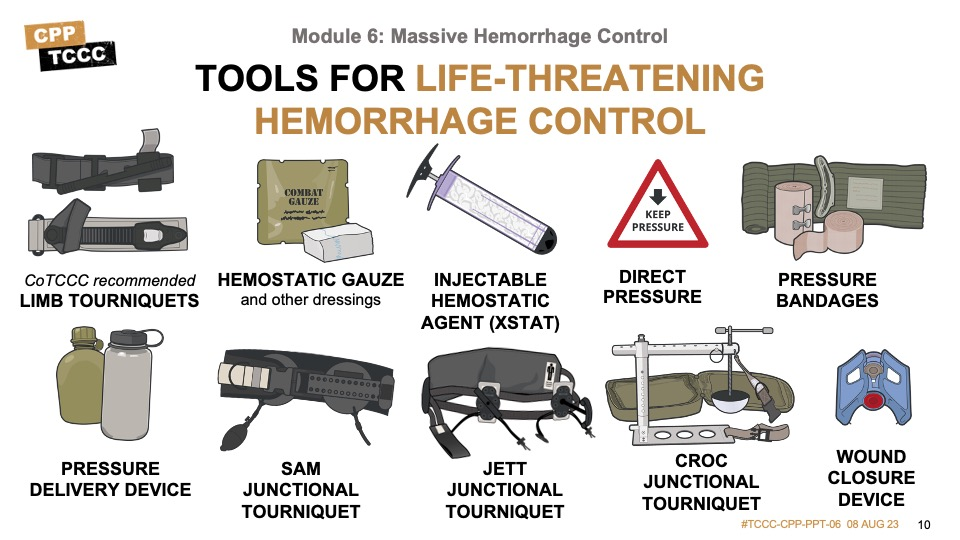

As Combat Paramedics/Providers, there are several tools at your disposal to help with controlling massive hemorrhage. In addition to limb tourniquets, hemostatic dressings, injectable hemostatic agent, direct pressure, pressure bandages, and pressure delivery devices, there are additional tools including junctional tourniquets and wound closure devices.

As mentioned in the prior modules, there may be more than one casualty and, as a combat medic, you may need to triage casualties and direct the actions of other responders before actually beginning individual casualty assessment. Triage ensures prioritization of available time, personnel, and medical supplies.

Massive bleeding is the #1 treatment priority.

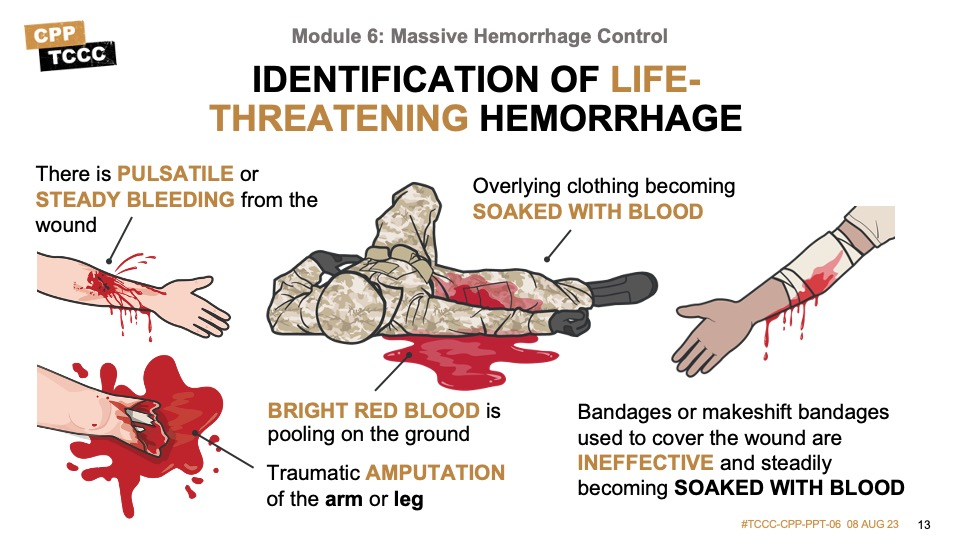

The following slide talks about signs of ongoing life-threatening bleeding that may not have been noted or appropriately addressed in Care Under Fire. These include pulsatile blood, steady bleeding from the wound, blood pooling on the ground or soaking overlying clothing or bandages, or blood flowing at the site of a traumatic amputation of an arm or leg. Any obvious ongoing life-threatening bleeding should be addressed immediately.

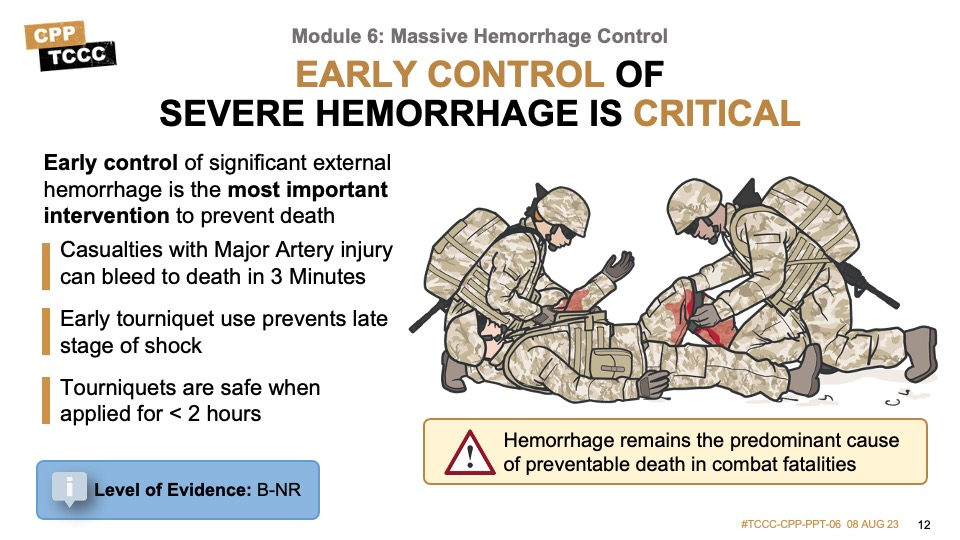

- Casualties with Major Artery injury can bleed to death in 3 Minutes

- Early tourniquet use prevents late stage of shock

- Limb exsanguination and saves lives. Tourniquets are safe when applied for < 2 hours.

- Nonindicated tourniquet placement is common (even when CUF is included as an indication).

- Morbidity is uncommon when tourniquet use is relatively brief. Prolonged (> 6 hours) use of a tourniquet can potentially result in the loss of a limb.

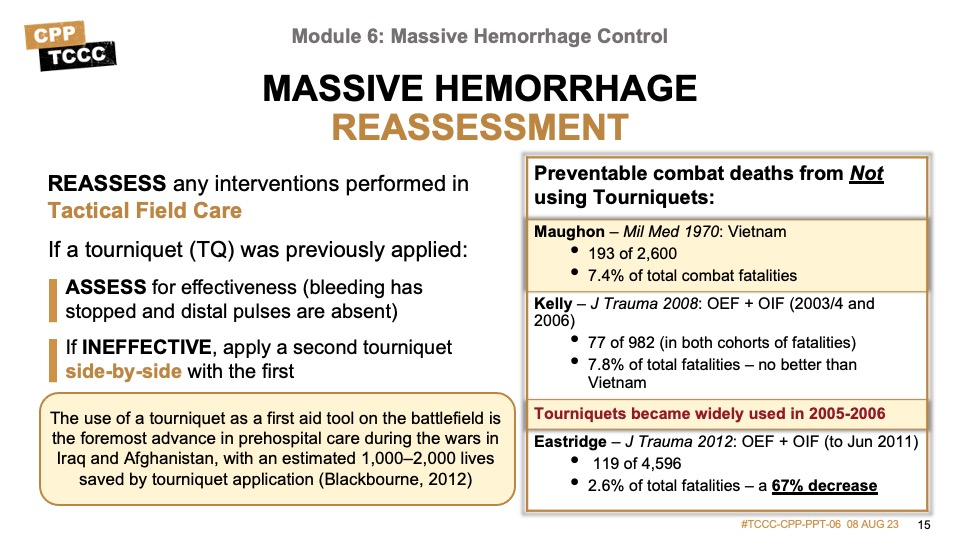

In combat casualties, early control of significant external hemorrhage is the most important intervention that can be undertaken. During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 lives were saved by tourniquet application. Despite the fact that potentially preventable deaths from extremity hemorrhage had dropped from 7.8 percent noted in a study by Kelly study to 2.6 percent in a subsequent study by Eastridge, a decrease of 67 percent, hemorrhage remains the predominant cause of preventable death in combat fatalities.

Research supporting the early control of severe bleeding, whether from the use of tourniquets or from other control measures, has shown a positive impact in multiple military-based and civilian prehospital studies. Overall, the supporting level of evidence is moderate to strong for early control of severe hemorrhage.

The time it takes to lose a significant amount of blood with severe hemorrhage can be measured in minutes and any delays in control can have significant adverse effects. Every effort needs to be made to initiate and control severe bleeding prior to proceeding with the rest of your assessment and treatment plan.

Assess for unrecognized hemorrhage and control all sources of bleeding. Signs and symptoms of massive hemorrhage include:

- Pulsatile (or arterial) bleeding, distinguished by its bright red appearance

- Steady bleeding, which can be gushing arterial or even venous from a larger vein being disrupted

- Blood pooling on the ground

- Blood soaking overlying clothing

- Blood flowing at the site of a traumatic amputation of an arm or leg

- Blood-soaked bandages, which generally indicate that the injury requires a tourniquet or the wound wasn’t packed and bandaged correctly

Massive hemorrhage control interventions performed in Care Under Fire should be reassessed. Previously applied tourniquets should be assessed for effectiveness (bleeding has stopped and distal pulses are absent). If the tourniquet is not effective, apply direct pressure and tighten the original tourniquet and/or apply a second tourniquet. Depending on the situation, this could be placed side-by-side and proximal to the first one, but might also be placed directly on the skin 2 inches above the wound as we will discuss shortly.

Tourniquets are a temporary measure allowing effective hemorrhage control and should be applied before shock to save lives.

Why tourniquets instead of pressure dressings?

Rapid control of severe (life-threatening) bleeding

Tourniquets allow for quick and direct occlusion of blood flow to the injured limb, which can be critical in cases of severe bleeding that cannot be controlled by traditional pressure dressings alone. Tourniquets can rapidly stop blood loss and provide valuable time for further medical interventions.

Effective in arterial bleeding

Tourniquets are particularly effective in managing high-pressure arterial bleeding, which can be challenging to control with pressure dressings alone. By completely stopping blood flow to the affected limb, tourniquets can effectively halt severe arterial bleeding until more definitive medical care can be provided.

Simple and easy application

Tourniquets are designed to be simple and quick to apply, even in high-stress situations. They typically consist of a strap or band and a mechanical or windlass mechanism that can be easily tightened to achieve sufficient pressure and occlusion of blood flow.

Enhanced stability and compression

Tourniquets provide stable and consistent compression to the injured limb, reducing the risk of rebleeding or blood loss when compared to pressure dressings, which may shift or become dislodged over time.

Prolonged effectiveness

Tourniquets can maintain effective hemorrhage control for an extended period, allowing for safe transport of the injured person to a medical facility. This can be particularly important in situations where medical help may be delayed or difficult to access, such as in remote or austere environments.

Before moving on to the rest of your assessment and treatment plan, always remember to reassess the massive hemorrhage control interventions performed in Tactical Field Care. This reassessment should become second nature as you go through your tactical trauma assessment process, and only takes a few moments. Previously applied tourniquets should be assessed for effectiveness (bleeding has stopped and distal pulses are absent). If the tourniquet is not effective, apply direct pressure and tighten the original tourniquet and/or apply a second tourniquet side-by-side and proximal to the first one.

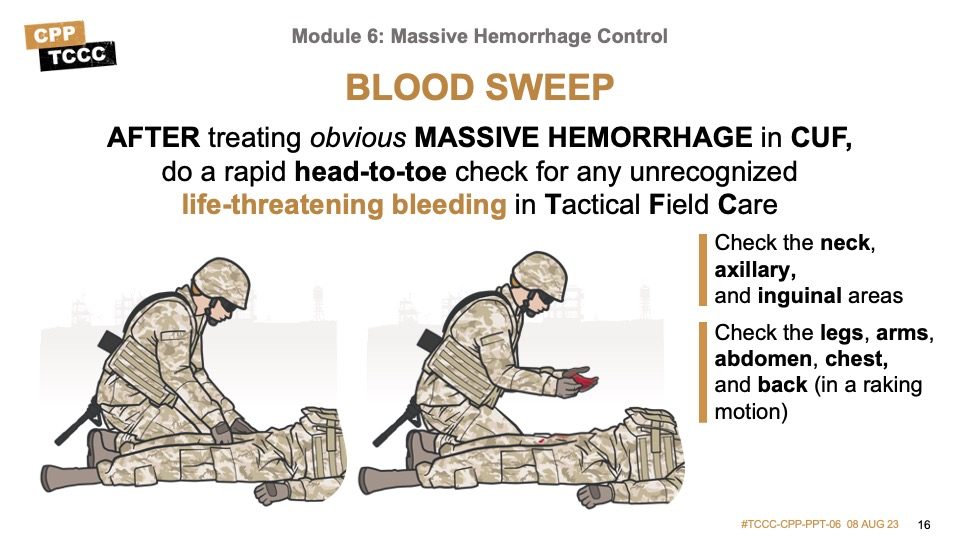

The Tactical Trauma Assessment (TTA), as you learned in the previous module, includes a head-to-toe check for any unrecognized life-threatening bleeding (called a blood sweep). This blood sweep is a visual and hands-on inspection of the front and back of the casualty from head to toe, including the neck, armpits, and groin.

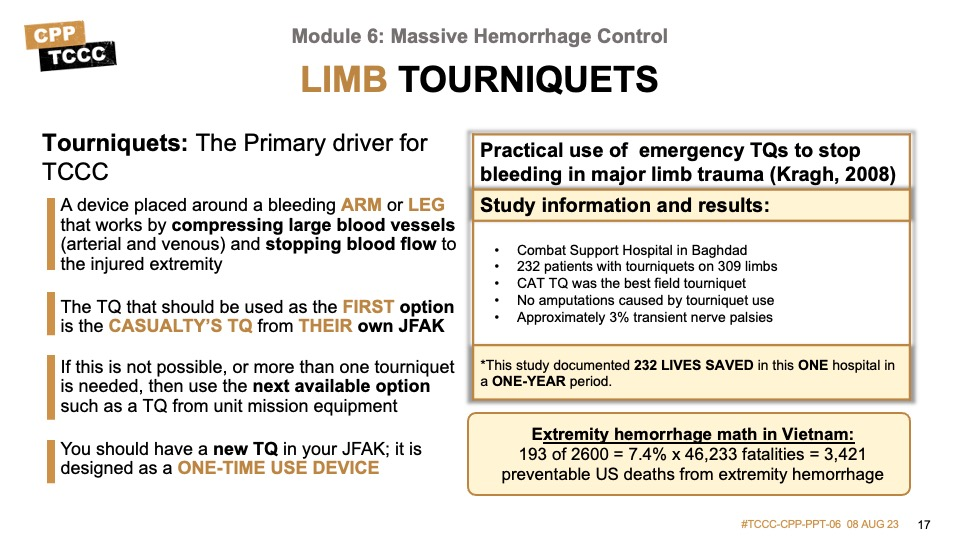

Tourniquets function by compressing blood vessels (arterial and venous) and stopping blood flow to the injured extremity. As arteries and larger veins follow the course of the skeletal system, the compression against bones is part of their mechanism of action; and also explains why it is sometimes difficult to control bleeding in lower leg and forearm injuries, where the arteries and large veins transit between the two bones and it is more difficult to attain or maintain adequate compression.

Because of their effectiveness at hemorrhage control, the speed with which they can be applied, and the lack of a requirement to hold sustained direct pressure on the bleeding site, tourniquets are the best option for temporary control of life-threatening extremity hemorrhage in the tactical environment.

The Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care routinely reviews tourniquets to help guide the selection of tourniquets with a proven track record of effectiveness. So, a CoTCCC-recommended limb tourniquet (TQ) should be applied quickly to all wounds that are amenable when ongoing severe bleeding is noted. 3,421 is a staggering number when all these deaths were potentially preventable.

“The striking feature was to see healthy young Americans with a single injury of the distal extremity arrive at the magnificently equipped field hospital, usually within hours, but dead on arrival. In fact there were 193 deaths due to wounds of the upper and lower extremities, …… of the 2600.” (Maughon JS)

Be sure to use the casualty’s TQ from their JFAK first (every Service member should have a new TQ in their JFAK). But if that is not possible, or more than one tourniquet is needed, then use the next available option, such as a TQ from unit mission equipment.

Also, remember that a tourniquet is designed as a one-time use device. Service members should never deploy with a tourniquet that has been used previously in training, as there is an increased risk of device failure.

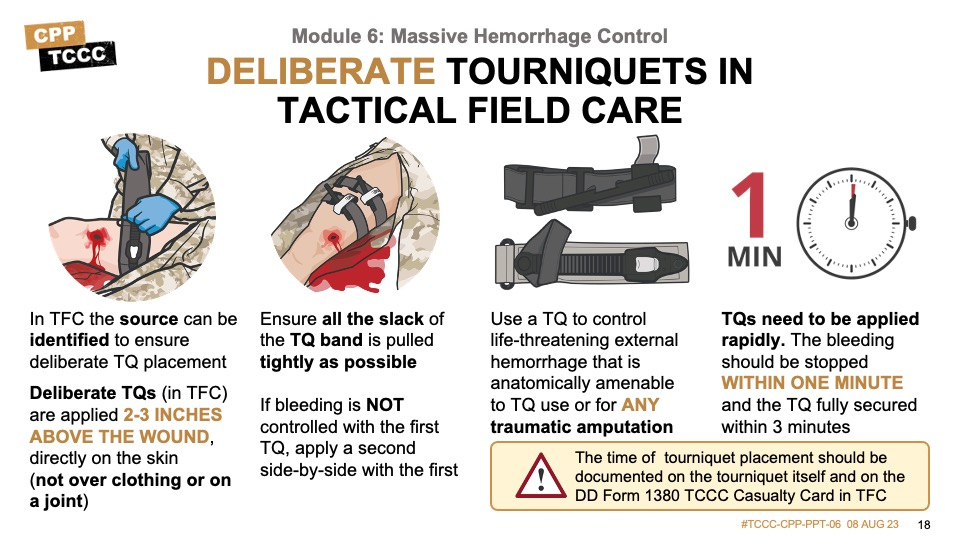

In TFC, there is more time to expose the wound and determine the actual site of bleeding. TQs should be applied more deliberately in the TFC setting 2 to 3 inches above the wound and directly on the skin to maximize effectiveness and minimize the amount of healthy tissue that might be impacted by a TQ placed too high on the limb. Do not put tourniquets over the knee, elbow, a holster, or other equipment, or a cargo pocket containing bulky items, as these locations and materials prevent adequate vascular compression.

If bleeding is not controlled and the distal pulse absent after the first TQ has been placed in TFC, it may be necessary to apply a second TQ side-by-side and proximal on the limb to the first.

All traumatic amputations warrant tourniquet placement, as bleeding may restart, even if it appears to have stopped due to the initial injury or perhaps the lack of circulating blood volume.

Ideally, bleeding should be stopped within one minute of recognition that life-threatening hemorrhage is present.

The time of tourniquet placement should be documented on the tourniquet itself and on the DD Form 1380 TCCC Card in TFC.

Tactical Field Care also allows the responder time to check tourniquet effectiveness and to document the time of placement.

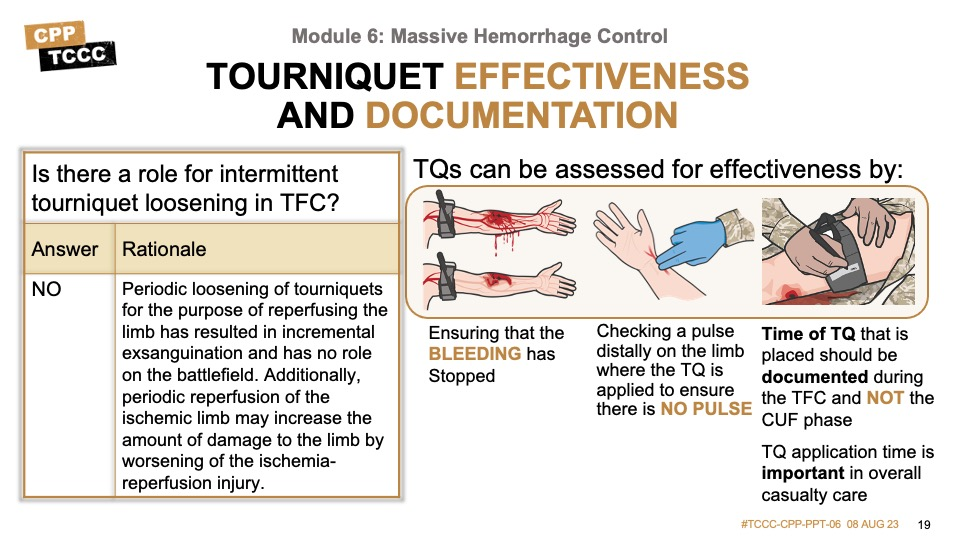

The effectiveness of a tourniquet can be assessed by ensuring that bleeding has stopped and by checking for a pulse distally on the limb from where the tourniquet has been applied.16 If bleeding continues or you detect a pulse, tighten the existing tourniquet or apply a second tourniquet next to the first, more proximally on the limb.

The time of tourniquet placement should be documented on the tourniquet itself and on the DD 1380 in TFC (and not during Care Under Fire/Threat).

Ineffective tourniquet use remains common, and in one process improvement project published in 2012, 83% of limbs treated with a tourniquet had palpable distal pulses and 74% did not have a major vascular injury; concurrently, no major vascular injury presented without a tourniquet. (King 2012-3)

During the early part of World War II, medical personnel briefly loosened tourniquets every 30 minutes, to allow reperfusion via intact collateral circulation. As a result, death sometimes occurred from the cumulative effects of the bleeding. Wolff and Adkins found that an unacceptable number of soldiers died as a result of incremental exsanguinations from repeated loosening of the tourniquet, and the practice justifiably was abandoned.

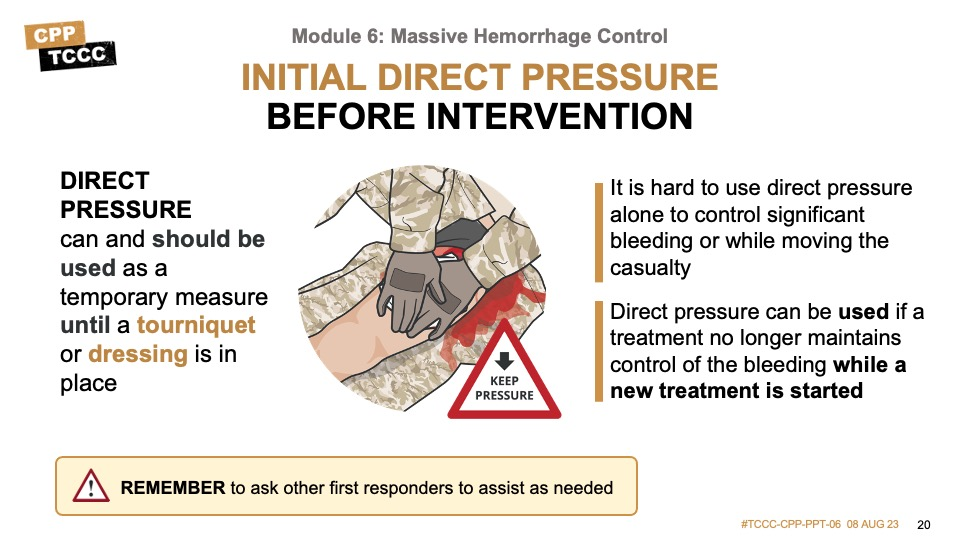

Several hemorrhage control guidelines recommend that any obvious bleeding in a compressible area should be treated with direct digital pressure first, as direct pressure can effectively control bleeding and be used as a temporary measure until a tourniquet or dressing can be applied. Although it is difficult to maintain direct pressure to control significant bleeding when working alone or while moving a casualty, it should be attempted while gathering and preparing equipment for more definitive treatment. When possible, ask other responders to assist in order to avoid releasing pressure while preparing for a more definitive hemorrhage control measure.

The exact site for applying direct pressure requires adequate exposure and assessment of the bleeding source. In cases of severe hemorrhage, it may be very difficult to determine the exact source of bleeding without exposing and exploring the wound carefully. And, in some cases, the source may not be easily identified.

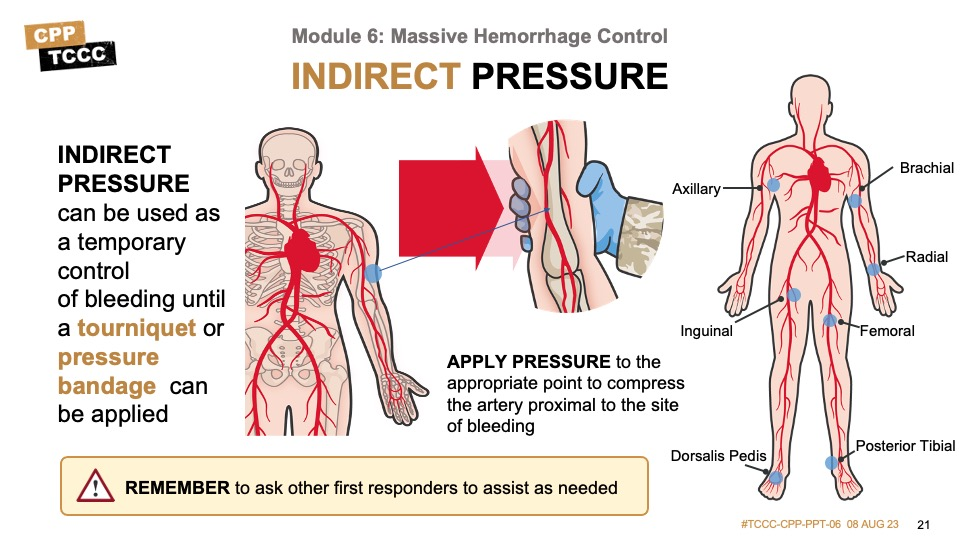

In cases where direct pressure is not possible, either because the exact source cannot be identified or because it is not amenable to direct pressure, indirect pressure can be used as a temporary measure to effectively control bleeding until a tourniquet or pressure dressing can be applied. It involves applying pressure to the appropriate pressure point to compress the artery proximal to the site of bleeding. The pressure points are located at anatomic areas where the arteries supplying blood to the injured area are superficial enough that they can be manually compressed against the underlying bone or soft tissue structures. This requires a great deal of pressure and, like a tourniquet, is painful when performed correctly.

As with direct pressure, it is hard to use indirect pressure alone to control significant bleeding or while moving a casualty, but it should be attempted while gathering and preparing equipment for more definitive treatments. Do not forget to ask other first responders to assist as needed.

Now, we’ll view a couple of videos reviewing the steps involved in tourniquet application. This first video demonstrates the two-handed application of a ratchet tourniquet in TFC.

TWO-HANDED RATCHET TOURNIQUET IN TFC

This video demonstrates the two-handed application of a windlass tourniquet in TFC.

TWO-HANDED WINDLASS TOURNIQUET IN TFC

When possible, practice applying tourniquets to yourself and/or a partner.

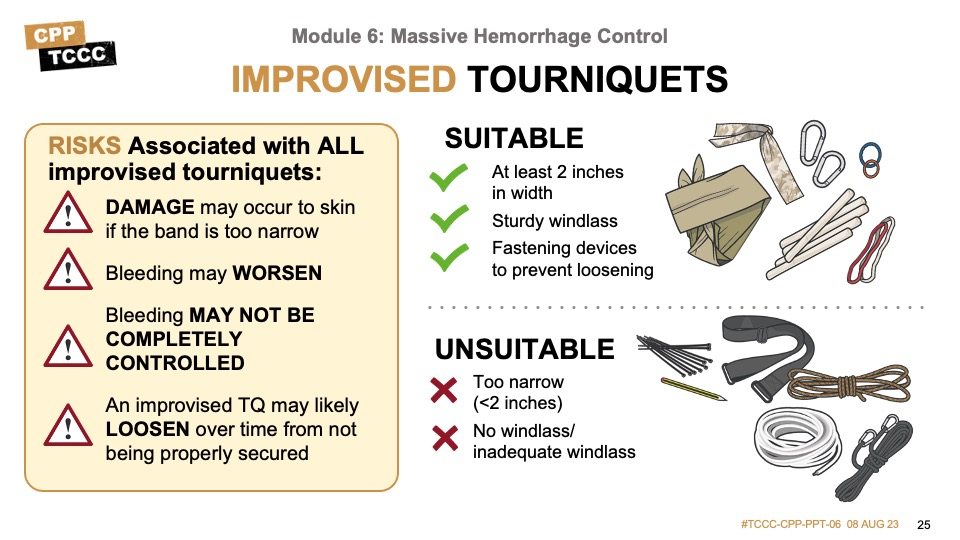

CoTCCC-recommended limb tourniquets should be used whenever possible. However, there may be occasions when your supply has been exhausted or you find yourself in a situation without one, and you might consider improvising a tourniquet. That said, improvised tourniquets should only be used as a last resort when there is no other available option to control life-threatening extremity hemorrhage.

If an improvised tourniquet must be utilized, use materials at least 2 inches in width for the strap to avoid excess tissue damage, and make sure that there isn’t too much elasticity in the strapping materials. The windlass materials need to be strong enough to turn the strap and something to secure the windlass and keep it from unwinding once control has been established is needed.

Continue to reassess improvised tourniquets after placement as they are prone to loosening and apply a CoTCCC-recommended tourniquet as soon as one becomes available.

Of 66 injured patients, 29 patients had recognized extremity exsanguination at the scene. In total, 27 tourniquets were applied: 16 of 17 traumatic amputations, 5 of 12 lower extremities with major vascular injuries, and 6 additional limbs with major soft tissue injury. All tourniquets were improvised, and no commercial, purpose-designed tourniquets were identified. Among all 243 patients, mortality was 0%.

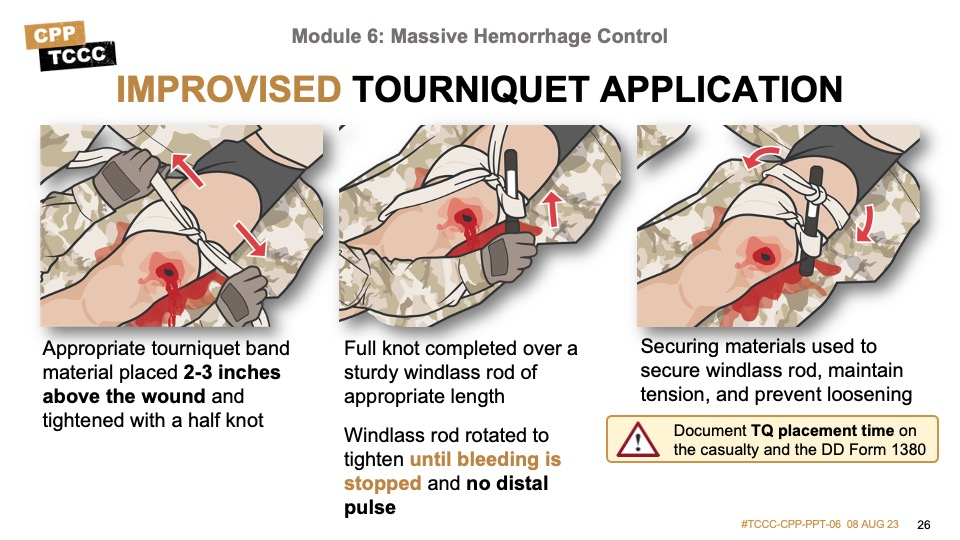

These steps show the proper application of an improvised tourniquet used as a last resort to control life-threatening hemorrhage. Ensure that the tourniquet band material used is at least 2 inches in width, that a sturdy windlass rod of appropriate length is used to ensure adequate tension can be applied and maintained, and that a securing device is used to secure the windlass in place and maintain tension once the bleeding has been stopped and the distal pulse is absent.

A pair of chopsticks as an improvised tourniquet windlass worked better than pencils or craft sticks. (Kragh, 2015)

This video demonstrates the application of an improvised limb tourniquet.

IMPROVISED LIMB TOURNIQUET

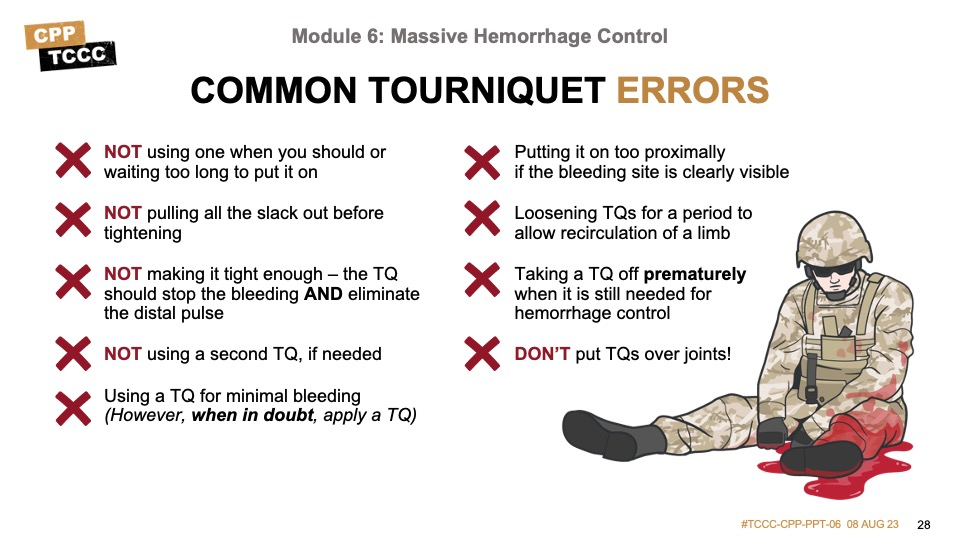

Before proceeding to the skill station and practicing tourniquet application, it might be helpful to review some of the common errors seen in tourniquet application, so that you can avoid them. These include, but are not limited to:

- Waiting too long to apply the tourniquet or not using one when indicated

- Not removing all of the slack in the strap before tightening the tourniquet

- Not tightening the tourniquet enough to stop bleeding and eliminate the pulse

- Not using a second tourniquet, if needed

- Using a tourniquet when one is not needed

- Putting a tourniquet “high and tight” rather than 2-3 inches above the wound when the bleeding site is clearly visible

- Loosening tourniquets for a period of time to allow recirculation of blood to an injured limb

- Removing a tourniquet prematurely when it is still needed for hemorrhage control

- Placing tourniquets over knee or elbow joints

Remember that tourniquets hurt when applied properly. Communicate this to the casualty while making them aware that it is being done to save their life.

The following skill cards will demonstrate and help you practice hemorrhage control techniques, including the application of CoTCCC-recommended windlass and ratchet limb tourniquets as well as improvised limb tourniquets.

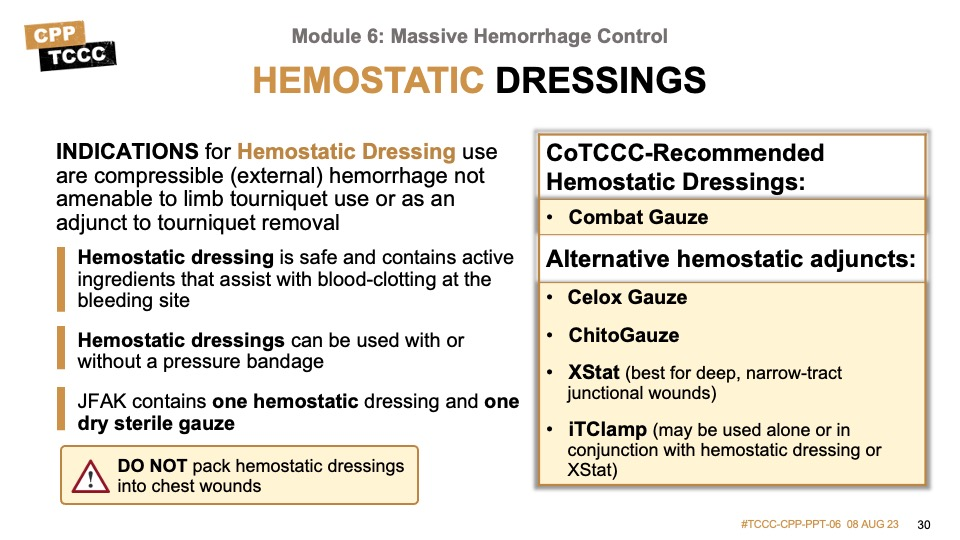

When the first TCCC Guidelines were published in 1996, there were no hemostatic dressing options approved by the FDA, and recommendations to research potential solutions was prioritized. As a result, by the 2003 edition of the Guidelines, two agents were approved and recommended for use by the CoTCCC: the chitosan-based bandage HemCon® and the zeolite powder QuikClot®. However, because an exothermic reaction when QuickClot powder was activated led to some burns, it was a second-line agent. Once additional options became available, it was no longer recommended.

Subsequently, several new agents have been developed and extensive evidence has been gathered that has allowed the CoTCCC to reliably recommend the use of QuikClot Combat Gauze®, ChitoGauze®, and/or Celox Gauze®. All participants with shellfish allergy tolerated the HemCon® bandage without reaction.

- QuikClot Combat Gauze is a non-woven material impregnated with kaolin, an inorganic mineral that activates Factor XII, which accelerates the body’s natural clotting ability.

- ChitoGauze dressing is composed of polyester/rayon blend non-woven medical gauze that is coated with chitosan, where an electrostatic interaction between the negatively charged cell membranes of erythrocytes and the positively charged chitosan forms an adherent gel, which tamponades the wound, but also accelerates the wound healing process by stimulating inflammatory cells, macrophages, and fibroblasts.

- Celox Gauze is also chitosan-based and shares the same mechanism of action. Although chitosan is derived from Chitin, which is found naturally in crustacean exoskeletons, it will not cause an allergic reaction in casualties with a shellfish allergy.

As mentioned when talking about wound packing principles, CoTCCC-recommended hemostatic gauze dressings must be packed into the wound to maximize contact at the active source of bleeding (in order to effectively form a clot at the site of the bleeding), with direct pressure applied over the wound for at least 3 minutes.

Hemostatic dressings should not be packed into chest wounds.

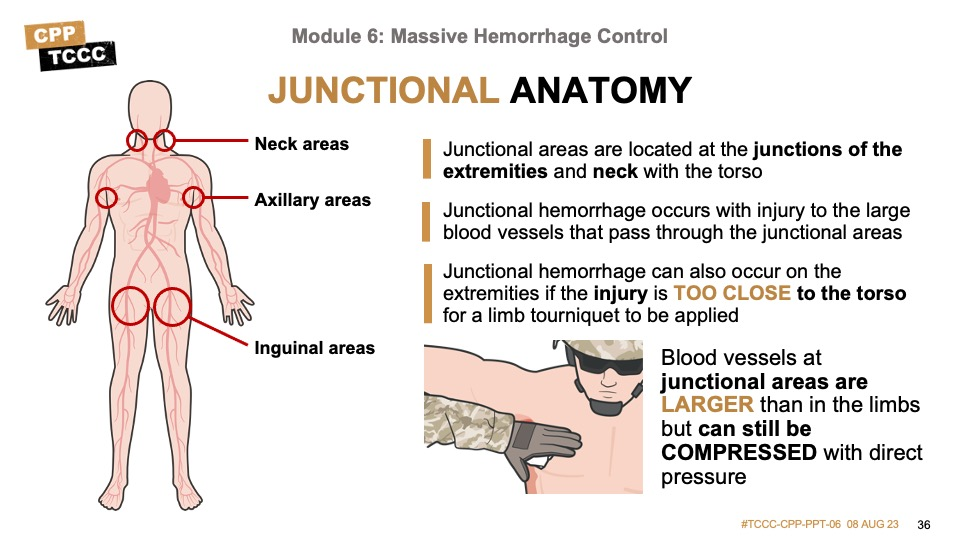

Not all external hemorrhage is amenable to hemorrhage control using limb tourniquets. Often this is due to the anatomical location of the injury, either being too proximal on an extremity to allow for a limb tourniquet to compress the site of bleeding or an injury that is not on the extremity, but on the torso or neck, particularly in the junctional areas where the extremities meet the torso or the base of the neck.

Additionally, not all bleeding on extremities requires a tourniquet for adequate bleeding control. In these cases, an alternative strategy is to pack the wounds (with hemostatic dressings or plain gauze) and apply a pressure bandage. The principles of wound packing and applying pressure bandages apply to situations when hemostatic dressings are being used and when non-hemostatic gauze or dressings are being used.

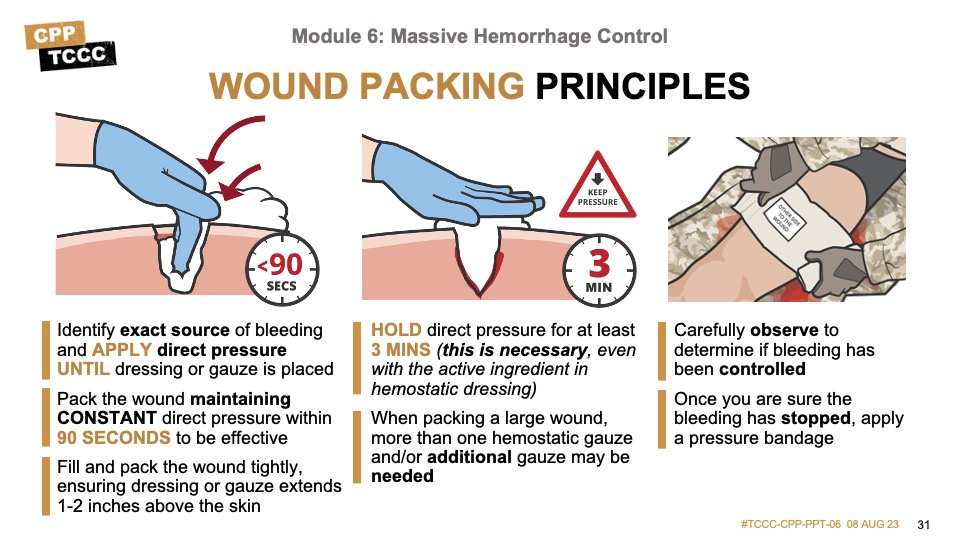

Whenever possible, identify the exact source of bleeding and apply direct pressure as a temporary measure while preparing hemostatic dressings (preferable) or gauze for placement. Pack the wound maximizing contact between hemostatic dressing or gauze and the active site of bleeding. Maintain constant direct pressure at the source of bleeding while packing the wound.

After the wound has been packed, hold direct pressure over the dressing on the wound for at least 3 minutes. This is necessary even with the active hemostatic agent in the dressing. When packing a large wound, more than one hemostatic dressing and/or additional gauze may be needed.

Carefully observe the wound to determine if bleeding has been effectively controlled. Once bleeding has been controlled, apply a pressure bandage.

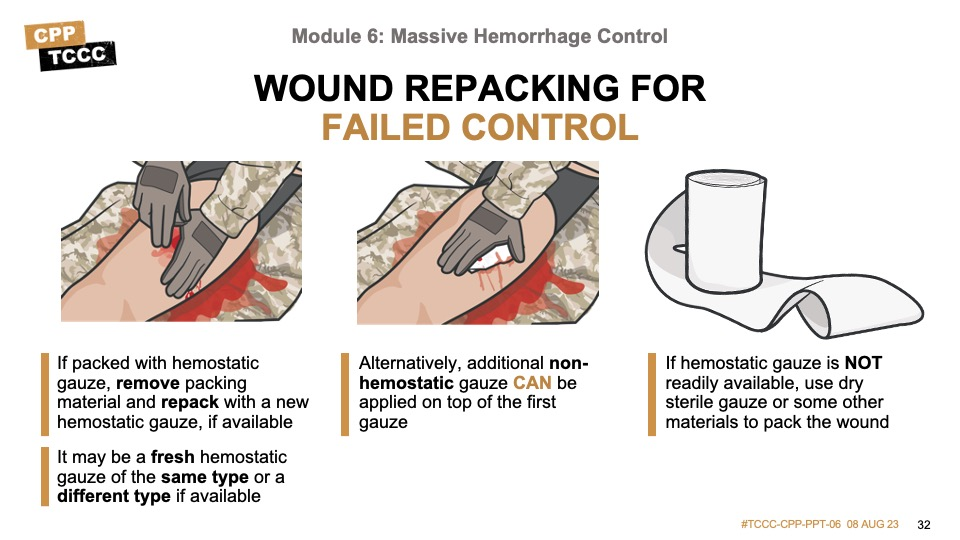

If a wound packed with hemostatic gauze continues to bleed after 3 minutes of direct pressure, remove the packing material and repack with a new hemostatic gauze, if available. This allows fresh, inactivated, clotting agents to come in contact with the source of bleeding and will hopefully lead to clot formation and hemorrhage control.

However, if additional hemostatic gauze is not available or the wound was packed with a non-hemostatic gauze dressing, reinforce the dressing with additional non-hemostatic gauze, apply direct pressure for three minutes, and then apply a pressure bandage to control the bleeding.

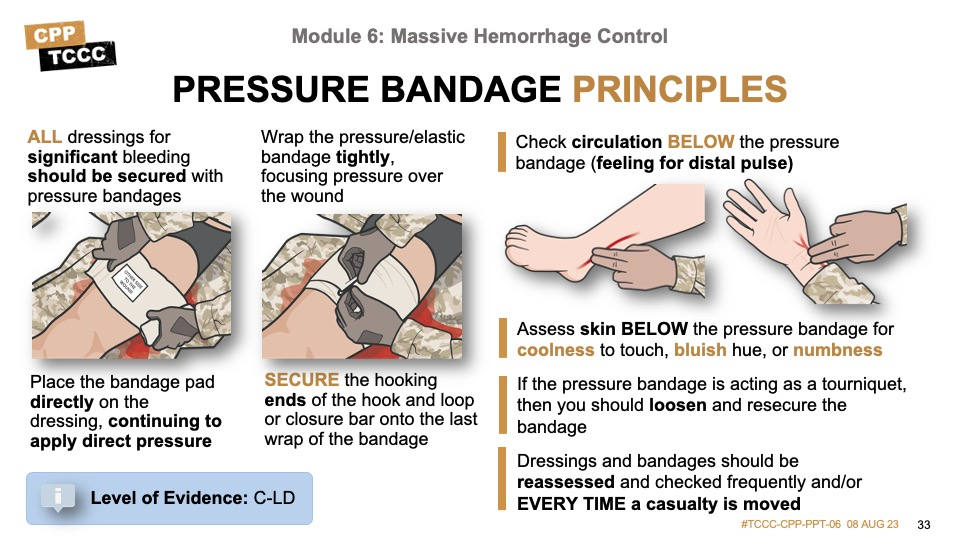

All dressings for significant bleeding should be secured with a pressure bandage. Although it may seem intuitive that all Combat Paramedics/Providers are familiar with pressure bandage application and principles, significant variation has been noted in both civilian and military studies looking at pressure bandage practices.

In several studies, it has been shown that pressure bandages with a pressure bar are equal to or superior to those without a pressure bar. The bar is very effective in elevating the applied pressure directly under the pressure bar while at the same time not applying unnecessary pressure over other areas covered by the bandage, which allows control of hemorrhage at the site of injury (under the pressure bar area) without having to have a full tourniquet effect. However, not all units deploy with bandages that utilize a pressure bar, and familiarity with multiple bandages is desirable.

It is vitally important to maintain pressure on the wound throughout the process of applying the pressure bandage. The most common mistake is releasing pressure on the wound dressing to wrap the bandage. If another responder is available to assist, it is much easier to maintain active pressure. If using a pressure bar bandage, remember to reverse the direction of the wrap after a full wrap to push the bar down directly over the wound and dressing. And be sure to secure the bandage well, as they are prone to being caught during casualty movements or reassessments.

Comparison of Battle Dressings

- Emergency Bandage, H-Bandage, and Olaes®, all of which possess mechanisms to focus pressure, produced the highest peak pressures over the simulated wound site.

- Battle Wrap™ did not achieve the target contact pressure.

- Honeycomb Bandage was the only device to significantly reduce distal blood flow. (Dory, 2022)

Remember, a pressure bandage should be tight but is not supposed to be a tourniquet.

After applying a pressure bandage, check for circulation distal to the bandage. If the skin below the bandage is cool, bluish in color, or numb indicating decreased circulation or if the distal pulse is absent, the pressure bandage may be too tight. The pressure bandage should be loosened slightly and resecured. All dressing and bandages should be reassessed frequently and especially after a casualty has been moved.

The following video demonstrates the technique for packing wounds using hemostatic dressings.

HEMOSTATIC DRESSING AND WOUND PACKING

The following skill cards will demonstrate and help you practice hemorrhage control techniques, including wound packing with a hemostatic dressing, application of a pressure dressing, and application of an injectable hemostatic agent.

As mentioned briefly in the introduction to wound packing, the junctional areas are located at the junctions of the extremities and neck with the torso. Junctional hemorrhage occurs with injury to the large blood vessels that pass through the junctional areas or to the extremities themselves if the injury is too close to the torso to allow for a limb tourniquet to be applied. Junctional hemorrhage is compressible external hemorrhage and must be treated without delay. Although blood vessels at the junctional areas are larger than in the limbs, they can still be compressed and a hemostatic dressing and direct pressure should be applied immediately, and application of a commercial or improvised junctional tourniquet should be considered.

The major areas of concern are the axillae, the groin, and the base of the neck, and we will review some techniques unique to each anatomic location, as each of them presents their own challenges. Control of bleeding from junctional areas and noncompressible torso bleeding remains the greatest challenge in prehospital trauma care. (van Oostendorp, 2016)

The TCCC Guidelines state:

“If the bleeding site is amenable to use of a junctional tourniquet, immediately apply a CoTCCC-recommended junctional tourniquet. Do not delay in the application of the junctional tourniquet once it is ready for use. Apply hemostatic dressings with direct pressure if a junctional tourniquet is not available or while the junctional tourniquet is being readied for use.”

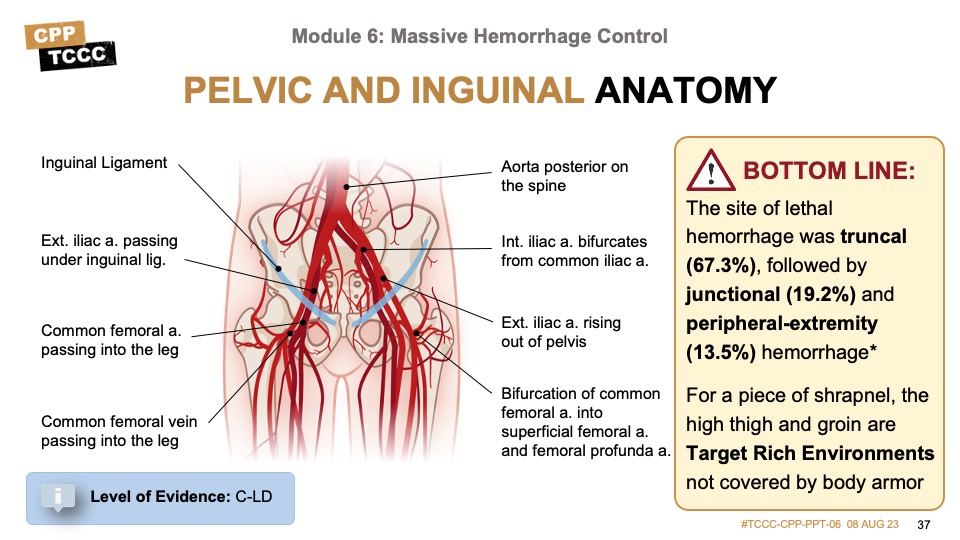

Although some of the commercial tourniquets that we’ll talk about can be used at other junctional areas, most of them have been designed with application to inguinal junctional hemorrhage in mind. Likewise, the improvised compression device we’ll review also primarily targets the inguinal region. Pelvic and inguinal hemorrhage have comprised the majority of the junctional bleeds that have been seen in recent conflicts. This is likely a function of the fact that body armor offers less protection to this area and many improvised explosive device injuries affect the lower body preferentially over the upper body.

The anatomy of the inguinal area does, however, offer easier access to the blood vessels for compression, and provides a mechanical advantage for maintaining pressure that is not seen in axillary and neck injuries. It is even possible to compress the aorta in some cases, although it is difficult to maintain adequate compression for an extended period of time.

The site of lethal hemorrhage was truncal (67.3%), followed by junctional (19.2%) and peripheral-extremity (13.5%) hemorrhage. (Eastridge, 2012)

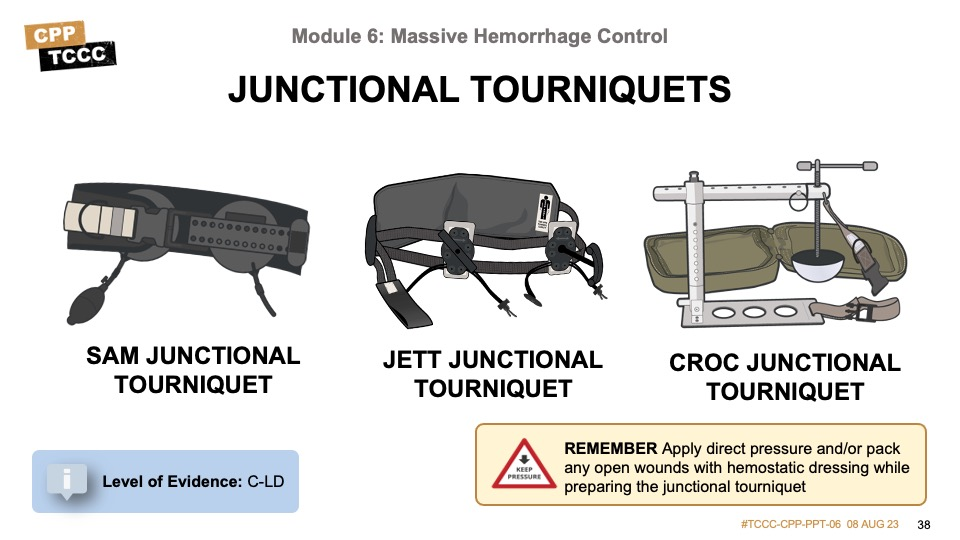

Although the current TCCC Guidelines indicate that you should use a CoTCCC-recommended junctional tourniquet, the CoTCCC-Recommended Devices & Adjuncts booklet states that “No specific products are recommended by the CoTCCC. End users may select any FDA approved device that is indicated for junctional hemorrhage control that will meet this requirement.” The three commercial devices we’ll highlight in this module meet those criteria, but there are others available. It is important to familiarize yourself with the devices that you are most likely to come across when deployed, as you will be the subject matter expert responsible for their application and training Combat Medics/Corpsmen or others in their use.

The desired traits for a junctional hemorrhage have been defined in several prior articles and military research documents, and include efficacy, safety, adaptability to the tactical environment, lightweight, low-cost, low-profile, easy to use, and quickly applied, to mention a few. Although each FDA-approved device has different advantages and disadvantages, most of them meet many of these criteria.

The wound should be packed with a hemostatic dressing with direct pressure while the tourniquet is readied for use, or with gauze if a hemostatic dressing is not available. But do not delay in the application of a junctional tourniquet once it is ready for use.

- Junctional tourniquets are designed to stop bleeding at the junctional areas.

- If the bleeding site is amenable, a junctional tourniquet should be applied immediately.

- Do not delay in applying a junctional tourniquet once it is ready for use.

- The wound should be packed with a hemostatic dressing with direct pressure while the tourniquet is readied for use.

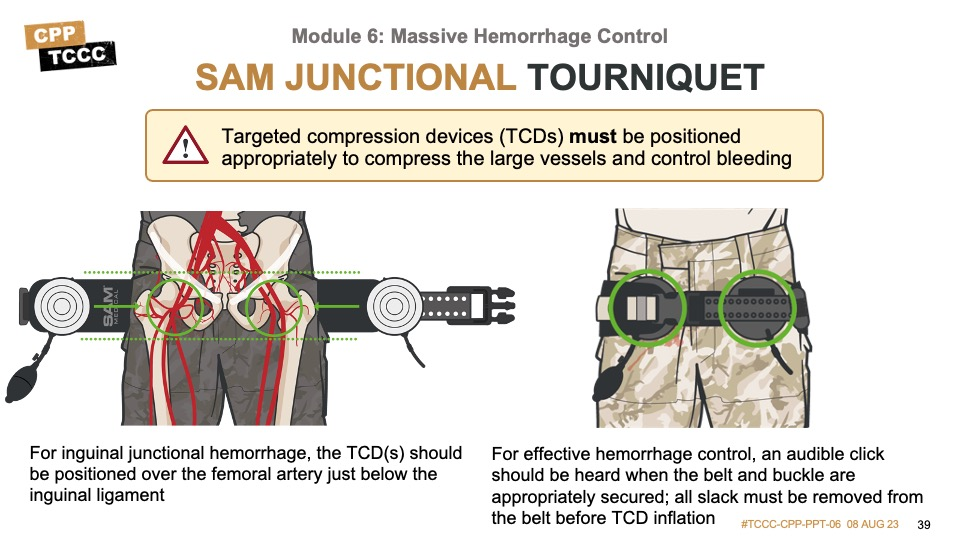

The SAM® Junctional Tourniquet is one of the FDA-approved junctional tourniquets. One advantage is that is designed to provide pelvic compression (with the circumferential belt) as well as direct pressure over either inguinal or axillary junctional wounds with the targeted compression devices (TCDs).

It is important that you have an understanding of basic junctional anatomy to ensure the TCDs are positioned appropriately to compress the large blood vessels and effectively control bleeding.

For inguinal junctional hemorrhage, the TCD(s) should be positioned over the femoral artery just below the inguinal ligament or just below the midpoint of the imaginary line between the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle, if femoral pulse is not palpable.

For effective hemorrhage control, an audible click should be heard when the belt and buckle are appropriately secured; all slack must be removed from the belt before TCD inflation.

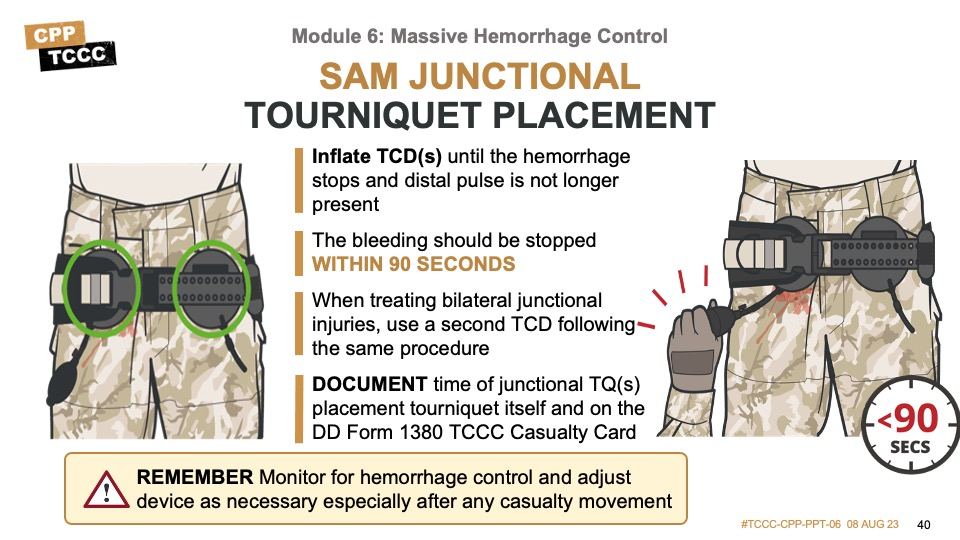

For the inguinal location, once the TCD is appropriately positioned, the belt is buckled and all slack is removed from the belt prior to TCD inflation. Often a click will be heard or felt. Once the TCD is secured in the correct position, the TCD is inflated using a hand pump until the hemorrhage stops and a distal pulse is no longer present. Bleeding should be stopped within 90 seconds. When treating bilateral junctional injuries, a second TCD can be utilized following the same procedure.

For the axillary location, the circumferential belt is secured before attaching the auxiliary strap. The auxiliary strap is not tightened until the TCD is in position, after which it can be pulled tight. Then, as with the inguinal approach, the hand pump is used to inflate the TCD until the bleeding stops and a distal pulse is no longer present.

DOCUMENT time of junctional TQ(s) placement tourniquet itself and on the DD Form 1380 TCCC Card.

The following video demonstrates the technique for use of the SAM Junctional Tourniquet to control massive hemorrhage from a junctional wound.

SAM JUNCTIONAL TOURNIQUET

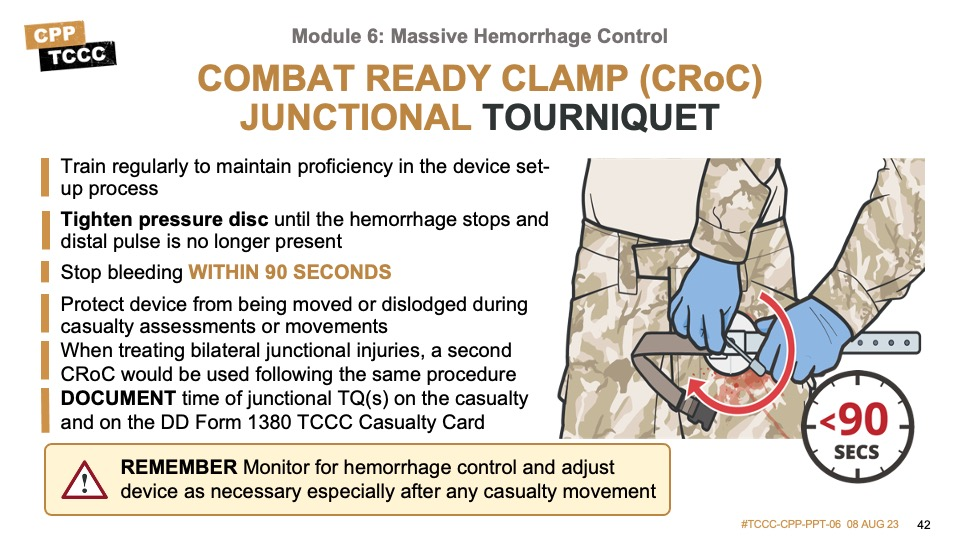

The Combat Ready Clamp is the third FDA-approved commercial junctional tourniquet we’ll highlight. It is designed to provide direct pressure over junctional wounds or pressure points with a pressure disc. Although there has been a little more research and a few more case reports of its use in axillary junctional bleeds, the design of the device, with the arm extended away from the casualty’s body, makes its use in upper extremity injuries more challenging. The same design consideration also creates a challenge in maintaining pressure disc location during casualty movements. Also, the steps to set up the CRoC are slightly more involved than the other junctional tourniquets, and users should train and refresh themselves on proper application before and during deployments.

Like the SAM junctional splint target compression device, the pressure disc should be positioned over the femoral pulse just below the inguinal ligament or just below the midpoint of the imaginary line between the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle, if the femoral pulse is not palpable. And for axillary junction hemorrhage, the pressure disc should be applied just below the clavicle next to the shoulder.

Once positioned properly, rotate the handle to tighten the pressure disc on the injured side until bleeding has stopped and a distal pulse is no longer palpable. Monitor for hemorrhage control and adjust the device as necessary, especially after any casualty movement. To treat additional junctional injuries, a second CRoC device would be used following the same procedure.

The following video demonstrates the technique for use of the CRoC to control massive hemorrhage from a junctional wound.

COMBAT READY CLAMP (CRoC) JUNCTIONAL TOURNIQUET

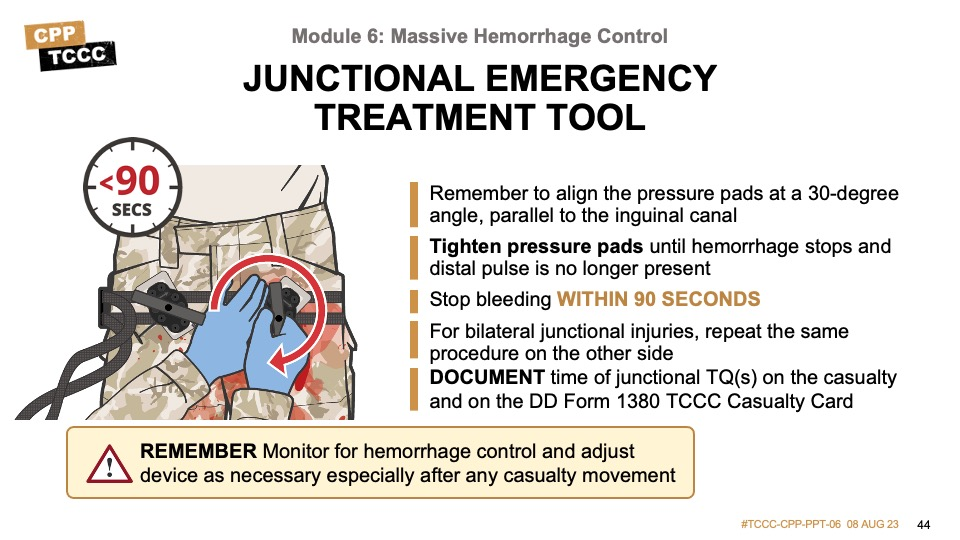

The Junctional Emergency Treatment Tool (JETT) is another of the three CoTCCC-recommended junctional tourniquets.

Similar to the SAM, it is designed to provide pelvic compression (with the circumferential belt) as well as direct pressure over inguinal junctional wounds with the junctional pressure pads.

The junctional pressure pads should be positioned over the femoral pulse just below the inguinal ligament or just below the midpoint of the imaginary line between the anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle, if femoral pulse is not palpable.

Adjust the two junctional pressure pads on the straps to position them in the area over the femoral pulse just below the inguinal ligament. Angle the junctional pressure pads so that their long axis is lined up with (parallel to) the inguinal canal or gutter (the distal part of the pad will be pointed somewhat laterally at approximately a 30-degree angle).

Once the pads are appropriately positioned, the belt is buckled and all slack should be removed from the belt before tightening the threaded T handle on the injured side until bleeding has stopped and distal pulse is no longer palpable.

This video demonstrates the technique for use of the JETT junctional tourniquet to control massive hemorrhage from a junctional wound.

JUNCTIONAL EMERGENCY TREATMENT TOOL

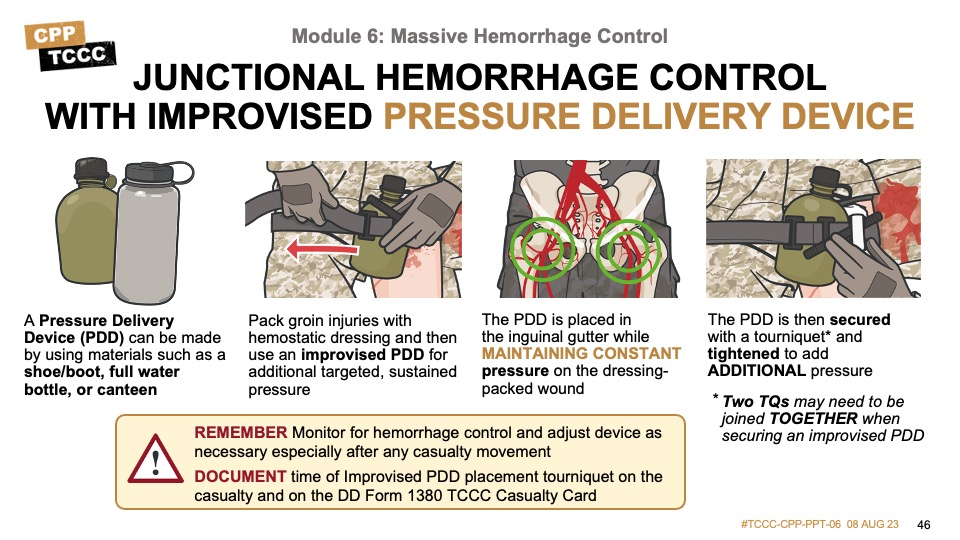

A commercial junctional tourniquet will not always be available, and it is important to understand some additional procedures to supplement wound packing with hemostatic dressings and pressure bandages. An improvised junctional pressure delivery device (PDD) may be needed to apply additional, targeted, and sustained pressure to control junctional bleeding.

One of the difficulties in maintaining pressure on an inguinal wound is that the anatomy of the pelvic ring creates a challenge for pressure bandages to maintain the mechanical advantage they have when used on an extremity. Commercial tourniquets overcome this by using relative rigid retaining devices with pressure applied by inflated pads or pressure discs/pads that are tightened down. In their absence, medics involved in the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan developed some alternate options for maintaining pressure by making improvised PDD using materials that are readily available on the battlefield including limb tourniquets, water bottles, canteens, boots, shoes, etc.

An improvised PDD works by placing a solid object over the same pressure points that are used in commercial junctional tourniquets, and then applying pressure using limb tourniquets. The PDD is large enough that it sits above the pelvic ring to provide the necessary mechanical advantage, and the tourniquet allows for pressure that exceeds a normal pressure bandage to be applied. This combination creates pressure that can equal that of a commercial junctional tourniquet.

The PDD is placed in the inguinal gutter while continuously maintaining pressure on the hemostatic dressing or gauze packed wound. It is then secured using two limb tourniquets joined together around the casualty’s body and around the PDD (although in some casualties a single tourniquet may suffice). As the tourniquet’s windlass or ratchet is tightened, pressure is applied to the PDD over the wound until the bleeding is stopped and the distal pulse absent.

The following video demonstrates the technique for use of an improvised junctional PDD to control massive hemorrhage from a junctional wound.

INGUINAL IMPROVISED JUNCTIONAL PDD

Of the potentially survivable injuries reviewed in the 2011 Eastridge study on preventable combat deaths, of the 90.9% related to hemorrhage, 19.2% were junctional injuries. Junctional injuries were further classified as 60.8% located in the axilla or groin and 39.2% located in the cervical region. This means that 7.5% of the total potentially survivable injuries were noted to be in the neck.

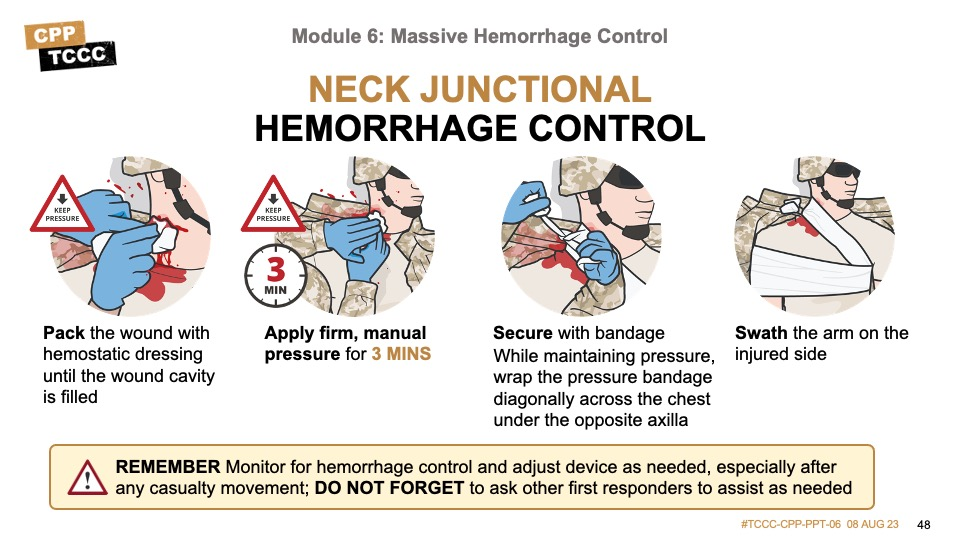

Junctional hemorrhage from a wound to the neck can be challenging to treat. Unlike inguinal and axillary junctional wounds that might be treated with a junctional tourniquet applying direct pressure to the site of injury or compressing a pressure point, the risk of cerebral vascular compromise from completely stopping the blood flow makes their use unadvisable, as a rule. That said, like all junctional wounds, they are amenable to proper wound packing and pressure bandage application, and there are techniques to help maintain pressure without having to dedicate another responder to continuous application of direct pressure.

The wound should be exposed, packed with hemostatic dressing mounded to at least 1-2 inches above the skin, and direct pressure should be applied continuously for a minimum of 3 minutes. After bleeding has been controlled continue to maintain pressure on the wound. Apply a pressure bandage by wrapping an elastic bandage over the wound on the neck on the affected side, diagonally across the body and under the opposite armpit, and then secure it with a nonslip knot. Swath the upper arm on the injured side to the chest using a cravat or another bandage. Continue to reassess for hemorrhage control especially after casualty movement. Do not forget to ask other first responders to assist as needed.

The following video demonstrates the technique for neck junctional hemorrhage control.

NECK JUNCTIONAL HEMORRHAGE CONTROL

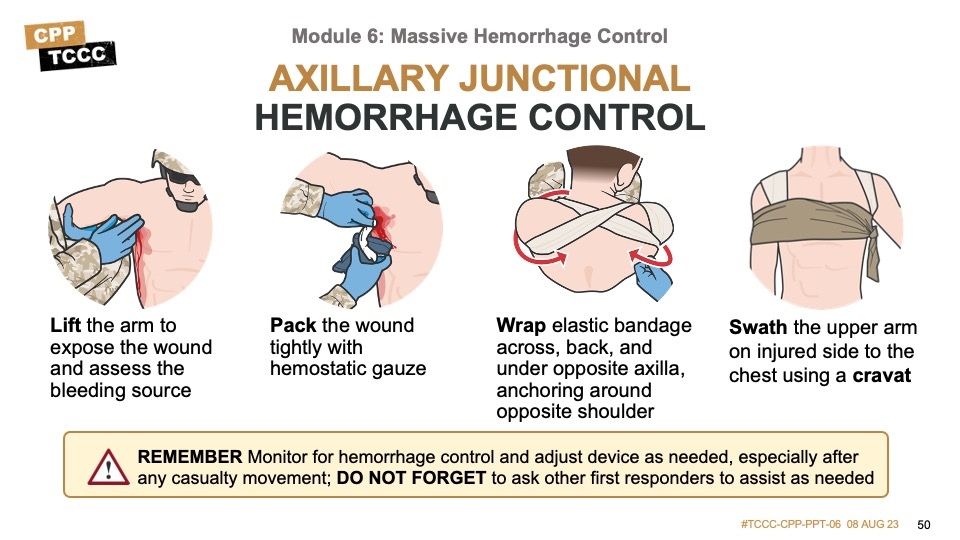

There are case reports and basic research into the use of commercial junctional tourniquets in axillary junctional hemorrhage, including another FDA-approved device, the Abdominal Aortic Tourniquet™, but many times they are not available or have been used on another casualty or at another site. As with neck wounds, junctional hemorrhage from a wound to the axillary region can be similarly challenging to treat. And, also like neck wounds, one approach is to perform wound packing with hemostatic dressings and apply pressure bandages using techniques that help maintain pressure without needing continuous direct manual pressure provided by another responder.

The wound should be exposed, packed with hemostatic dressing mounded to at least 1-2 inches above the skin, and direct pressure applied continuously for a minimum of 3 minutes. After bleeding has been controlled continue to maintain pressure on the wound. Apply a pressure bandage by wrapping an elastic bandage circumferentially around the shoulder and under the armpit twice on the affected side, diagonally across the body and under the opposite armpit and around the shoulder, and back across the body using a “figure 8” technique. Secure it with a nonslip knot or a securing device (depending on what type of bandage is used). Swath the upper arm on the injured side to the chest using a cravat or another bandage. The “figure 8” elastic bandage helps to maintain pressure on the wound when both arms are down at the casualty’s side. Continue to reassess for hemorrhage control, especially after casualty movement. Do not forget to ask other first responders to assist as needed.

The following video demonstrates the technique for axillary junctional hemorrhage control.

AXILLARY JUNCTIONAL HEMORRHAGE CONTROL

The following skill cards will demonstrate and help you practice junctional hemorrhage control techniques, including inguinal junctional hemorrhage control with both FDA-approved junctional tourniquets and an improvised junctional pressure delivery device (PDD), neck junctional hemorrhage control, and axillary junctional hemorrhage control.

READ FULL PDF

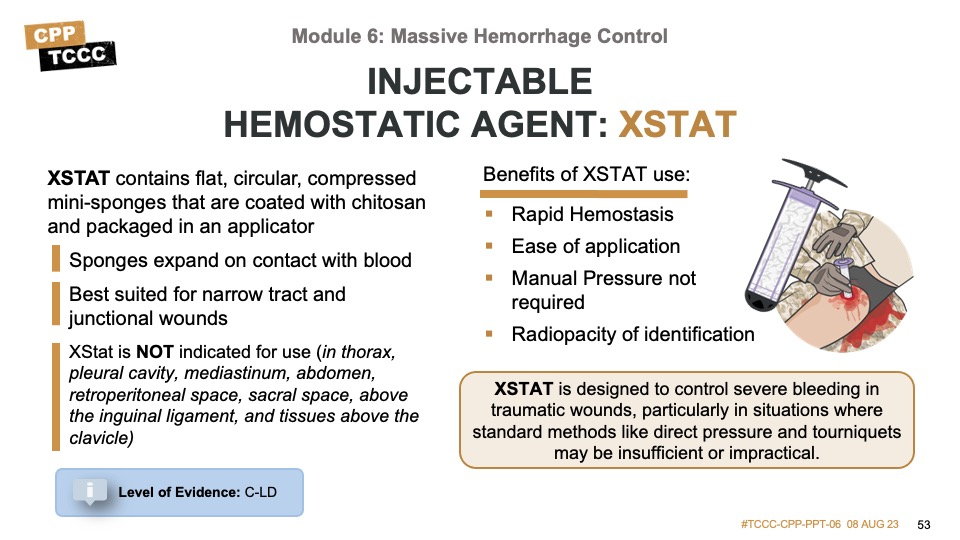

In response to the prioritization of junctional hemorrhage control, research studies into the potential application of expanding hemostatic agents were undertaken and the injectable hemostatic XStat™ was developed, receiving FDA approval for use on the battlefield in 2014, and in civilian settings in 2015. It offers another option for controlling external hemorrhage and is best suited for deep narrow tract and junctional wounds that are otherwise difficult to compress with external pressure.

The XStat system consists of flat, circular, compressed minisponges that are coated with chitosan and packaged in an applicator. The applicator has a small-diameter insertion device available for use in narrow wound tracts. XStat is injected into the wound cavity and the compressed hemostatic minisponges expand on contact with blood. The expanded sponges, now 12–15 times their original volume, exert pressure on the walls of the wound cavity from within, thereby eliminating the need for manual compression. The chitosan may promote clotting, but the tamponade effect of the expanded sponges is the primary mechanism of action. The research studies resulting in the FDA approval were performed in animal models, although there have been case reports of its successful use in humans since then.

The FDA approval is for the control of bleeding from junctional wounds in the groin or axilla not amenable to tourniquet application in adults and adolescents. XStat is a temporary device for use up to four hours until surgical care is acquired. XStat is NOT approved for use in the thorax, the pleural cavity, the mediastinum, the abdomen, the retroperitoneal space, the sacral space above the inguinal ligament, or tissues above the clavicle.

Each XStat minisponge has a radiopaque marker so the sponges can be located with radiography at the time of surgery. Do not attempt to remove sponges in the field.

XStat is an alternative hemostatic adjunct for compressible (external) hemorrhage not amenable to limb tourniquet use or as an adjunct to tourniquet removal. XStat is best for deep, narrow-tract junctional wounds and does not require additional manual pressure once administered.

XStat is designed to control severe bleeding in traumatic wounds, particularly in situations where standard methods like direct pressure and tourniquets may be insufficient or impractical. It consists of a syringe-like applicator filled with small, expandable sponges made from a proprietary material called "ChitoSAM," which is coated with chitosan, a naturally occurring compound that promotes blood clotting.

When the XStat is applied to a bleeding wound, the sponges are inserted into the wound cavity, where they expand and exert pressure to promote hemostasis (stopping bleeding). The sponges also contain a radiopaque marker, which allows for easy identification on X-rays in case surgical removal is required.

BENEFITS OF XSTAT

Rapid Hemostasis

XStat provides rapid hemostasis by exerting pressure on bleeding wounds, promoting clot formation, and reducing blood loss. The expandable sponges fill the wound cavity, creating a tamponade effect and facilitating clotting.

Ease of Application

XStat is designed for ease of use and can be quickly applied by medical personnel in high-stress environments. The syringe-like applicator allows for controlled and precise placement of the expandable sponges directly into the wound.

Does not require Manual Pressure

XStat does not require a 3-minute period of external manual pressure on the wound after application like other hemostatic dressings and adjuncts.

Radiopacity for Identification

XStat sponges contain a radiopaque marker, allowing for easy identification on X-rays. This feature helps locate and remove the sponges during surgical procedures if necessary.

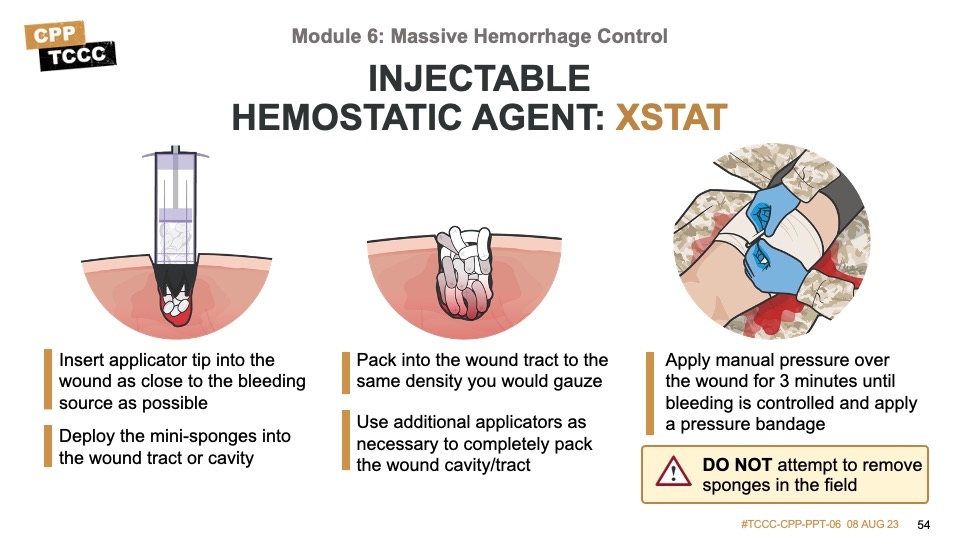

There are two sizes of the XStat delivery system. The original is larger, but the applicator may not fit into very narrow wound tracks, while the newer, smaller version has fewer sponges and may require more applicators. It is common to need more than one applicator. In fact, in one of the animal studies just mentioned, the average number of the larger applicators needed to achieve results was six.

To insert the injectable hemostatic agent, the wound should be exposed and direct pressure applied while preparing the device. Each device has a slightly different process to prepare for delivery, so become familiar with both of them when you train prior to and during deployments. Then insert the applicator tip into the wound tract and depress the plunger, deploying the sponges. You may need to begin to withdraw the applicator to continue to deploy additional sponges, until you have a mound that sits 1-2 inches above the level of the wound, as you would with standard wound packing. In a study comparing XStat to standard gauze (Kerlix) in a gel model of a simulated wound cavity, XStat was applied eight times faster (8 seconds versus 67 seconds) than packing the cavity with standard gauze. This study also found that XStat applied pressure more symmetrically throughout the wound cavity than did standard gauze.

The TCCC Guidelines state that direct pressure with XStat is optional;74 but although the expansion of the sponges within the wound cavity is designed to create internal pressure at the bleeding site, when tactically feasible it is still good practice to apply direct pressure to the wound for 3 minutes after application. And a pressure dressing should be placed over the wound to secure the agent, as well. It is important to document use of injectable hemostatic agents as the sponges are only for temporary use and will need to be removed surgically at a higher level of care.

This video demonstrates the technique for the application of injectable hemostatic agents to control hemorrhage.

INJECTABLE HEMOSTATIC AGENT (XSTAT)

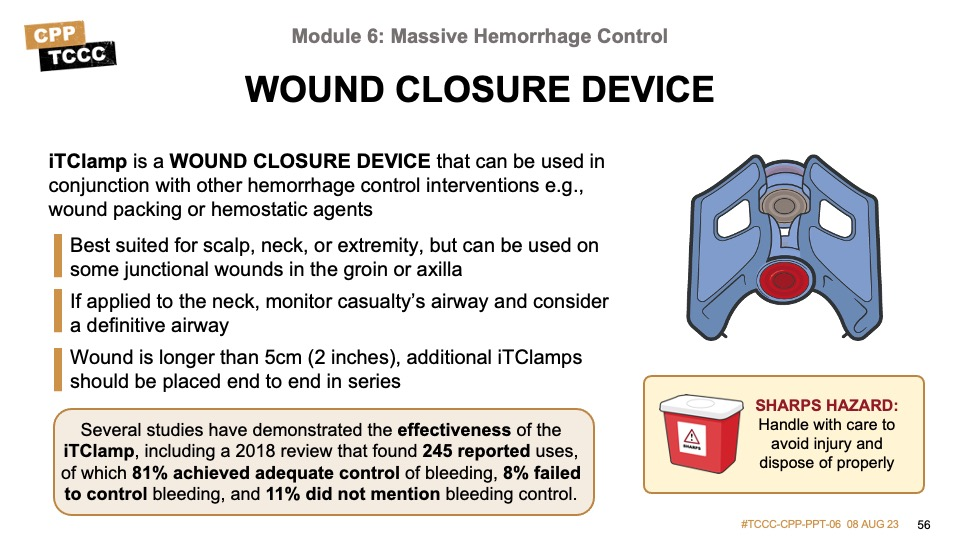

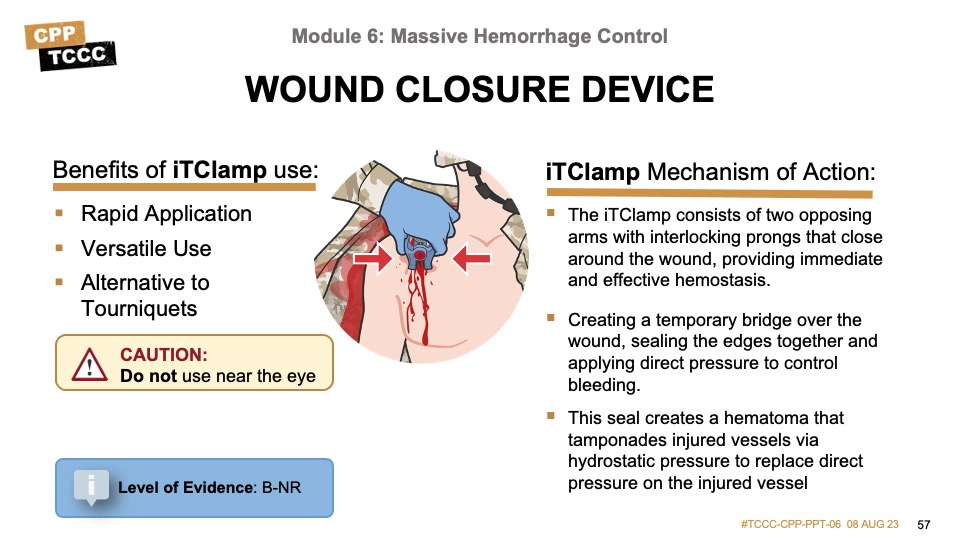

Another adjunct highlighted in the TCCC Guideline section on massive hemorrhage control is the use of a wound closure device, either alone or in conjunction with a hemostatic dressing or XStat. The Guidelines then go on to state that for head and neck wounds where the edges can be approximated, a wound closure device can be used as a primary option.

The incidence of craniomaxillofacial injuries (CMFI) and penetrating neck injuries increased from approximately 16% in Vietnam to 30.0% in the first 4 years of conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq, probably as a result of improved body armor protecting other common sites of injury (torso) and the increased use of improvised explosive devices. As previously discussed, the anatomic complexities of the head and neck make wounds in this region a challenge to treat, especially for the Role 1 provider, as they are not amenable to tourniquet use or circumferential pressure dressings. Also, the anatomy of the scalp makes compression challenging, and packing with hemostatic dressing is usually not possible. And CMFI and neck injuries are associated with a 10% to 50% mortality rate due to exsanguination. In response to this, in September 2018, the CoTCCC reviewed the literature on the clinical and experimental use of the iTClamp® as a wound closure device, resulting in its inclusion in the next set of TCCC Guidelines.

Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the iTClamp, including a 2018 review that found 245 reported uses, of which 81% achieved adequate control of bleeding, 8% failed to control bleeding, and 11% did not mention bleeding control. This wound closure device uses the hydrostatic backpressure of a hematoma inside a wound cavity to generate pressure and produce a hemostatic effect on the injured vessel. The device establishes a fixed fluid-tight seal through wound edge approximation, and this seal creates a hematoma that tamponades injured vessels via hydrostatic pressure to replace direct pressure on the injured vessel. In an animal model comparison to standard therapy with hemostatic dressings and pressure bandages combining the iTClamp and wound packing demonstrated improved survival and considerably reduced treatment times. Wound closure devices can be used with or without wound packing and hemostatic dressing for temporary wound closure and bleeding control (applying with hemostatic dressings is an off-label use, as this was not included in the FDA approval process).

The device is best suited for wounds on the scalp, neck, or extremities but can also be used on some junctional wounds in the groin or axilla. It can be applied quickly and if needed, can be removed and reapplied easily in the prehospital environment. For larger wounds or wounds with a significant cavity, more than one closure device and/or wound packing with hemostatic dressing prior to closure may be needed to control bleeding.

This video demonstrates the technique for applying an ITClamp® Wound Closure Device.

ITCLAMP® WOUND CLOSURE DEVICE

Mechanism of Action

The iTClamp consists of two opposing arms with interlocking prongs that close around the wound, providing immediate and effective hemostasis. It works by creating a temporary bridge over the wound, sealing the edges together and applying direct pressure to control bleeding. This seal creates a hematoma that tamponades injured vessels via hydrostatic pressure to replace direct pressure on the injured vessel.

Benefits in TCCC

Rapid Application

The device can be quickly and easily applied, even by non-medical personnel, which is crucial in combat situations where time is limited and immediate control of bleeding is essential.

Versatile Use

The iTClamp can be used on a variety of wounds, including lacerations, punctures, and surgical incisions. It is particularly useful in areas where tourniquets cannot be applied, such as junctional areas (e.g., groin, axilla).

Alternative to Tourniquets

The iTClamp provides a temporary solution to control bleeding for wounds that either are not amendable to tourniquets (head/neck) or use of tourniquets may unnecessarily completely occlude blood flow to a limb.

The following skill cards will demonstrate and help you practice junctional hemorrhage control techniques including inguinal junctional hemorrhage control with both FDA-approved junctional tourniquets and an improvised junctional pressure delivery device (PDD), neck junctional hemorrhage control, and axillary junctional hemorrhage control.

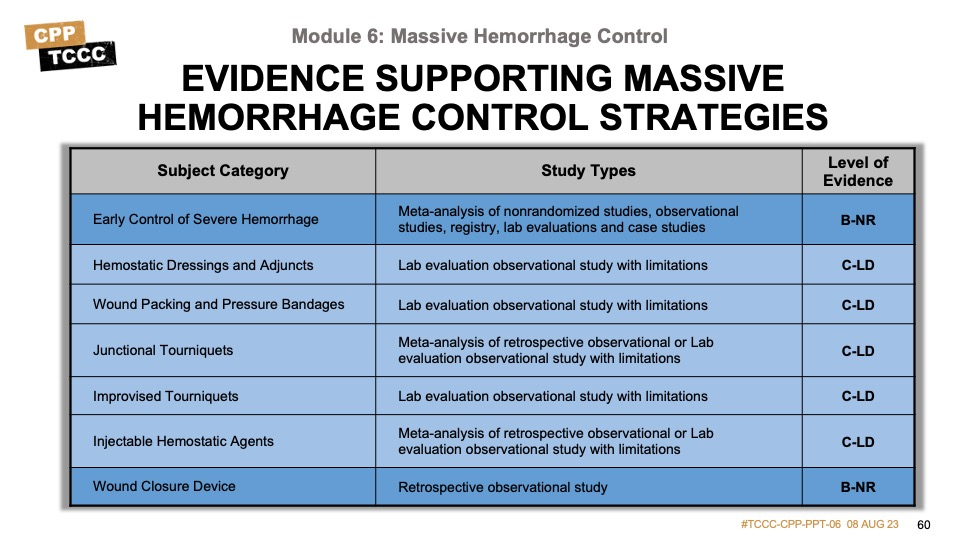

There is an abundance of evidence that limb tourniquets have a positive effect on clinical outcomes, and the early application leads to the best results. Likewise, the research and studies done on hemostatic dressings and pressure bandage application are significant, and these both reach the level of high supporting evidence.

The junctional hemorrhage measure evidence is robust, but not quite as extensive as the limb tourniquet and wound packing evidence; nevertheless, there is a moderate to high level of support for those strategies.

The evidence behind injectable hemostatic agents is less robust, with most of the studies being animal-based and the human studies focused on case reports and subject matter expert opinions, which is why it is rated as low to moderate.

And although the wound closure device also has subject matter expert opinion, there are some retrospective studies that help provide a moderate level of supporting evidence.

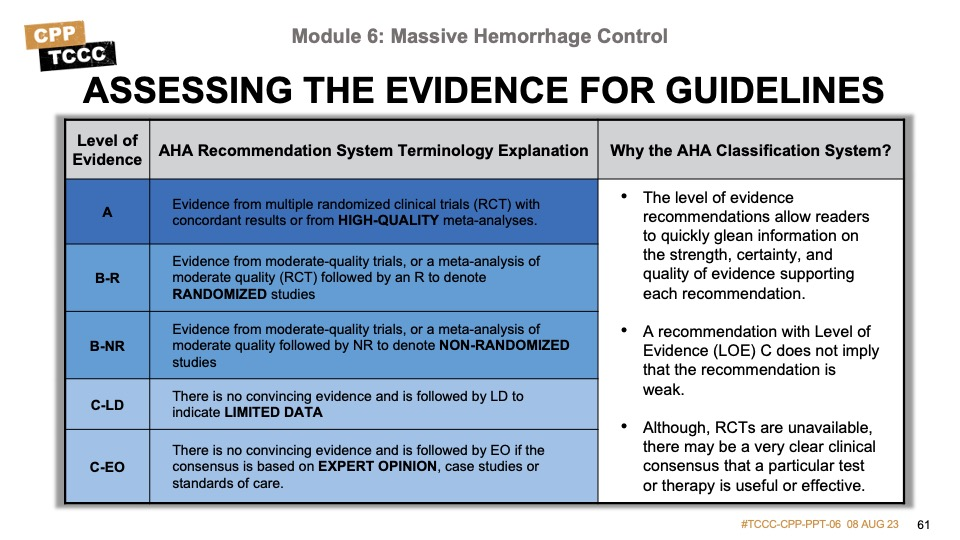

Evidence-based recommendations and guidance is the result of a careful review of studies and discussion by a panel of subject matter experts. For TCCC, the subject matter expert panels include both Committee on TCCC members, and select invited subject matter experts from within both the military and civilian community, based on the specific interest area.

Why the AHA Classification System?

The level of evidence classification combines an objective description of the existence and the types of studies supporting the recommendation and expert consensus, according to 1 of the following 3 categories1:

- Level of evidence A: recommendation based on evidence from multiple randomized trials or meta-analyses

- Level of evidence B: recommendation based on evidence from a single randomized trial or nonrandomized studies

- Level of evidence C: recommendation based on expert opinion, case studies, or standards of care.

The level of evidence recommendations allows readers to quickly glean information on the strength, certainty, and quality of evidence supporting each recommendation. The Level of Evidence (LOE) denotes the confidence in or certainty of the evidence supporting the recommendation, based on the type, size, quality, and consistency of pertinent research findings.

A recommendation with level of evidence C does not imply that the recommendation is weak. Many important clinical questions addressed in guidelines do not lend themselves to clinical trials. Although, Randomized Clinical Trials are unavailable, there may be a very clear clinical consensus that a particular test or therapy is useful or effective.

Summary

Identifying and controlling massive hemorrhage (the M in MARCH PAWS) remains the priority in Tactical Field Care.

All limb TQs hastily placed high and tight in CUF need to be reassessed and deliberate TQs placed for any extremity hemorrhage not previously addressed.

For external hemorrhage from sites not amenable to limb tourniquets (places where a tourniquet cannot be effectively applied) or for bleeding from wounds not requiring a tourniquet, direct or indirect pressure, a CoTCCC-recommended hemostatic dressing, and/or a pressure dressing can be used to control bleeding

Junctional hemorrhage is compressible external hemorrhage not amenable to limb TQs and must be treated without delay using CoTCCC-recommended junctional TQs or improvised junctional hemorrhage control techniques with hemostatic dressings and direct pressure.

Other methods for addressing massive hemorrhage include injectable hemostatic agents and wound closure devices.

To close out this module, check your learning with the questions below (answers under the image).

Answers

What is the proper distance a deliberate tourniquet should be placed from the bleeding site in Tactical Field Care?

- A deliberate TQ placed in Tactical Field Care should be 2-3 inches above (proximal) to the site of bleeding.

What are the differences between the high & tight/hasty tourniquets placed in CUF and the deliberate tourniquets placed in TFC?

- The tourniquets placed in CUF are typically placed over the uniform/clothing as high up on the extremity as possible as time is very limited and the exact site of bleeding may not have been identified.

- In contrast, the TQs placed in CUF are placed more deliberately after uniform/clothing have been removed and 2-3 inches above the identified site of bleeding.

How long should direct pressure be applied onto packed hemostatic dressings?

- 3 minutes.

Why is it important to check the pulse after applying a pressure bandage?

- A pressure dressing should not be a TQ.

- It is important to check to ensure a pulse is still present distally after bleeding has been controlled by application of a pressure dressing.

- If no pulse is present the pressure dressing should be loosened and reapplied.

What is inguinal junctional hemorrhage and how is it treated?

- Inguinal junctional hemorrhage is bleeding from the large blood vessels at the junction where the lower extremities join the torso.

- Injuries to these junctional areas are typically not amenable to a limb tourniquet and require other intervention.

- If available a CoTCCC-recommended junctional tourniquet should be applied.

- If not available, the wound should be packed with hemostatic dressing and direct pressure applied to the wound.

- Application of an improvised pressure delivery device may be needed to apply additional, targeted, and sustained pressure to control hemorrhage.

Injectable hemostatic agent is contraindicated in which types of wounds?

- This device is not indicated for use in chest or abdominal cavity wounds.

Blackbourne LH, Baer DG, Eastridge BJ, et al. Military medical revolution: prehospital combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73: S372–S377.

Kelly JF, Ritenhour AE, McLaughlin DF, et al. Injury severity and causes of death from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom: 2003–2004 vs 2006. J Trauma. 2008;64(suppl 2):S21–S26.

Eastridge BJ, Mabry R, Seguin P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012; 73(6).

Kragh JF Jr, Walters TJ, Baer DG, et al. Practical use of emergency tourniquets to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. J Trauma. 2008; 64: S38–S50.

Kragh JF Jr, Swan KG, Smith DC, et al. Historical review of emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding. Am J Surg. 2012; 203:242–252.

Kauvar DS, Dubick MA, Walters TJ, Kragh JF Jr. Systematic review of prehospital tourniquet use in civilian limb trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018 May; 84(5):819-825.

Peng HT. Hemostatic agents for prehospital hemorrhage control: a narrative review. Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):13. Published 2020 Mar 25.

Richey SL. Tourniquets for the control of traumatic hemorrhage: a review of the literature. J Spec Oper Med. 2009 Winter;9(1):56-64.

B-NR - Meta-analysis of multiple retrospective observational studies

Kragh, John F. Jr MC, USA*; Walters, Thomas J. PhD*; Baer, David G. PhD*; Fox, Charles J. MC, USA†; Wade, Charles E. PhD*; Salinas, Jose PhD*; Holcomb, John B. MC, USA*. Survival With Emergency Tourniquet Use to Stop Bleeding in Major Limb Trauma. Annals of Surgery 249(1):p 1-7, January 2009.

Maughon JS. An inquiry into the nature of wounds resulting in killed in action in Vietnam. Mil Med. 1970;135(1):8-13.

Warren E. An Epitome of Practical Surgery for Field and Hospital. Richmond, VA: West & Johnson; 1863.

Blizard W. A lecture on the situation of the large blood-vessels of the extremities; and the methods of making effectual pressure on the arteries. In: Cases of Dangerous Effusions of Blood From Wounds. Delivered to the Scholars of the Late Maritime School, at Chelsea. 3rd ed. London: Dilly; 1798.

Kragh JF Jr, Swan KG, Smith DC, Mabry RL, Blackbourne LH. Historical review of emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding. Am J Surg. 2012 Feb; 203(2):242-52.

Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 December 2021, Basic Management Plan for Tactical Field Care para 3.a. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 1 Mar 22.

Shackelford SA, et al. Optimizing the Use of Limb Tourniquets in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 14-02. J Spec Oper Med. 2015 Spring;15(1):17-31.

16Kragh JF Jr, Littrel ML, Jones JA, Walters TJ, Baer DG, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Battle casualty survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop limb bleeding. J Emerg Med. 2011 Dec;41(6): 590-7.

Bennett BL. Bleeding Control Using Hemostatic Dressings: Lessons Learned. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017 Jun;28(2S): S39-S49.

Butler FK Jr, Hagmann J, Butler EG. Tactical combat casualty care in special operations. Mil Med. 1996 Aug;161 Suppl:3-16.

Donley ER, Loyd JW. Hemorrhage Control. [Updated 2021 Jul 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535393/; accessed 1 Mar 2022.

Douma MJ, O'Dochartaigh D, Brindley PG. Optimization of indirect pressure in order to temporize life-threatening haemorrhage: A simulation study. Injury. 2016 Sep;47(9):1903-7.

Charlton NP, et al. Control of Severe, Life-Threatening External Bleeding in the Out-of-Hospital Setting: A Systematic Review. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021 Mar-Apr;25(2):235-267.

King DR, Larentzakis A, Ramly EP; Boston Trauma Collaborative. Tourniquet use at the Boston Marathon bombing: Lost in translation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(3): 594–599.

Bulger EM, Snyder D, Schoelles K, et al. An evidence-based prehospital guideline for external hemorrhage control: American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(2): 163-173.

Altamirano MP, Kragh JF Jr, Aden JK 3rd, Dubick MA. Role of the Windlass in Improvised Tourniquet Use on a Manikin Hemorrhage Model. J Spec Oper Med. 2015 Summer;15(2): 42-6.

Kragh JF Jr, Wallum TE, Aden JK 3rd, Dubick MA, Baer DG. Which Improvised Tourniquet Windlasses Work Well and Which Ones Won't? Wilderness Environ Med. 2015 Sep;26(3): 401-5.

Duignan KM, Lamb LC, DiFiori MM, Quinlavin J, Feeney JM. Tourniquet use in the prehospital setting: Are they being used appropriately? Am J Disaster Med. 2018;13(1):37-43.

Bennett BL. Bleeding Control Using Hemostatic Dressings: Lessons Learned. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017 Jun;28(2S): S39-S49.

Wright J.K. Kalns J. Wolf E.A. et al. Thermal injury resulting from application of a granular mineral hemostatic agent. J Trauma. 2004; 57: 224-230.

CoTCCC Recommended Devices & Adjuncts. Joint Trauma System. Available on Deployed Medicine at https://www.deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/100; accessed 2 Mar 22.

Griffin JH. Role of surface in surface-dependent activation of Hageman factor (blood coagulation factor XII). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Apr;75(4):1998-2002.

Lechner R, Helm M, Mueller M, Wille T, Friemert B. Efficacy of Hemostatic Agents in Humans with Rotational Thromboelastometry: An in-vitro Study. Mil Med. 2016 Aug;181(8): 907-12.

Xie, H, et al. Comparison of Hemostatic Efficacy of ChitoGauze and Combat Gauze in a Lethal Femoral Arterial Injury in Swine Model. 2010. Available at https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA581794.pdf; accessed 2 Mar 2022.

Bennett BL, et al. Management of External Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: Chitosan-Based Hemostatic Gauze Dressings--TCCC Guidelines-Change 13-05. J Spec Oper Med. 2014 Fall;14(3): 40-57.

Liu H., Wang C., Li C., Qin Y., Wang Z., Yang F., Li Z., Wang J. A functional chitosan-based hydrogel as a wound dressing and drug delivery system in the treatment of wound healing. RSC Adv. 2018;8: 7533–7549.

Waibel KH, Haney B, Moore M, et al. Safety of allergic patients. Mil Med 2011; 176:1153–1156.

David M, Gogi N, Rao J, Selzer G. The art and rationale of applying a compression dressing. Br J Nurs. 2010 Feb 25-Mar 10;19(4):235-6.

Dory R, Cox D, Endler B. Test and Evaluation of Compression Bandages. Naval Medical Research Unit San Antonio. NAMRU-SA REPORT #2014-52. Available at https://persysmedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/NAMRU-SA-Compression-Bandages-TR.pdf; accessed 2 Mar 2022.

Shipman N, Lessard CS. Pressure applied by the emergency/Israeli bandage. Mil Med. 2009 Jan;174(1):86-92.

Kotwal RS, et al. Management of Junctional Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Proposed Change 13-03. J Spec Oper Med. 2013 Winter;13(4): 85-93.

van Oostendorp, S.E., Tan, E.C.T.H. & Geeraedts, L.M.G. Prehospital Control of Life-threatening Truncal and Junctional Hemorrhage is the Ultimate Challenge in Optimizing Trauma Aare; A Review of Treatment Options and Their Applicability in the Civilian Trauma Setting. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 24, 110 (2016).

Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 December 2021, Basic Management Plan for Tactical Field Care para 3.b. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 2 Mar 22.

Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, Cantrell J, Tops T, Uribe P, Mallett O, Zubko T, Oetjen-Gerdes L, Rasmussen TE, Butler FK, Kotwal RS, Holcomb JB, Wade C, Champion H, Lawnick M, Moores L, Blackbourne LH. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Dec;73(6 Suppl 5): S431-7.

Schauer SG, April MD, Fisher AD, Cunningham CW, Gurney J. Junctional Tourniquet Use During Combat Operations in Afghanistan: The Prehospital Trauma Registry Experience. J Spec Oper Med. 2018 Summer;18(2): 71-74.

Oh JS, Tubb CC, Poepping TP, Ryan P, Clasper JC, Katschke AR, Tuman C, Murray MJ. Dismounted Blast Injuries in Patients Treated at a Role 3 Military Hospital in Afghanistan: Patterns of Injury and Mortality. Mil Med. 2016 Sep;181(9):1069-74.

Douma MJ, Picard C, O'Dochartaigh D, Brindley PG. Proximal External Aortic Compression for Life-Threatening Abdominal-Pelvic and Junctional Hemorrhage: An Ultrasonographic Study in Adult Volunteers. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019 Jul-Aug;23(4):538-542.

van Oostendorp, S.E., Tan, E.C.T.H. & Geeraedts, L.M.G. Prehospital Control of Life-threatening Truncal and Junctional Hemorrhage is the Ultimate Challenge in Optimizing Trauma Aare; A Review of Treatment Options and Their Applicability in the Civilian Trauma Setting. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 24, 110 (2016).

Combat Ready Clamp Junctional Tourniquet FDA Approval, available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf10/K102025.pdf; accessed 5 Mar 22.

Kotwal RS, Butler FK, Gross KR, Kheirabadi BS, Baer DG, Dubick MA, Rasmussen TE, Weber MA, Bailey JA. Management of Junctional Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines? Proposed Change 13-03. J Spec Oper Med. 2013 Winter;13(4): 85-93.

Mann-Salinas EA, Kragh JF Jr, Dubick MA, Baer DG, Blackbourne LH. Assessment of users to control simulated junctional hemorrhage with the combat ready clamp (CRoC™). Int J Burns Trauma. 2013;3(1): 49-54.

Kerr W, Hubbard B, Anderson B, Montgomery HR, Glassberg E, King DR, Hardin RD Jr, Knight RM, Cunningham CW. Improvised Inguinal Junctional Tourniquets: Recommendations From the Special Operations Combat Medical Skills Sustainment Course. J Spec Oper Med. 2019 Summer;19(2): 128-133.

Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, Cantrell J, Tops T, Uribe P, Mallett O, Zubko T, Oetjen-Gerdes L, Rasmussen TE, Butler FK, Kotwal RS, Holcomb JB, Wade C, Champion H, Lawnick M, Moores L, Blackbourne LH. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Dec;73(6 Suppl 5): S431-7.

Simpson C, Tucker H, Hudson A. Pre-hospital management of penetrating neck injuries: a scoping review of current evidence and guidance. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021 Sep 16;29(1):137.

Abdominal Aortic and Junctional Tourniquet FDA Approval Product Sheet, available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/k133029.pdf; accessed on 5 Mar 22.

Croushorn J, Thomas G, McCord SR. Abdominal aortic tourniquet controls junctional hemorrhage from a gunshot wound of the axilla. J Spec Oper Med. 2013 Fall;13(3):1-4.

XStat™ FDA Approval Product Sheet, available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf21/K210676.pdf; accessed 5 Mar 22.

Sims K. Management of junctional hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: use of non-absorbable, expandable, hemostatic sponge for temporary internal use. CoTCCC presentation; August 2015.

Sims K, Montgomery HR, Dituro P, Kheirabadi BS, Butler FK. Management of External Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: The Adjunctive Use of XStat™ Compressed Hemostatic Sponges: TCCC Guidelines Change 15-03. J Spec Oper Med. 2016 Spring;16(1): 19-28.

Mueller G, Pineda T, Xie H, et al. A novel sponge-based wound stasis dressing to treat lethal noncompressible hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73: S134–139.

Cestero RF, Song BK. The effect of hemostatic dressings in a subclavian artery and vein transection porcine model. Technical Report 2013=012. San Antonio, TX; Naval Medical Research Unit San Antonio; 2013.

https://www.jems.com/news/industry-news-news/revmedx-announces-first-field-use-of-xstat/; accessed on 5 Mar 22.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3609169/Wound-plugging-XStat-syringe-saves-life-battlefield-Device-uses-SPONGES-stop-bleeding-15-seconds.html; accessed on 5 Mar 22.

Cunningham AJ, McBride L, Zhao H, et al. Comparison of the effects of three hemostatic agents in a swine model of lethal femoral artery injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(2):346-354.

C-LD - Lab evaluation observational study with limitations - This study compared the efficacy of three hemostatic agents, including XStat, in controlling bleeding from a femoral artery injury in a swine model. It found that XStat was effective in achieving hemostasis and reducing blood loss, supporting its use in severe arterial bleeding.

Cox JM, Rall JM. Evaluation of XSTAT® and QuickClot® Combat Gauze® in a Swine Model of Lethal Junctional Hemorrhage in Coagulopathic Swine. J Spec Oper Med. 2017 Fall;17(3):64-67.

C-LD - Lab evaluation observational study with limitations – The study compared the efficacy of XStat and combat gauze on 19 swine models. XStat achieved hemostasis faster and maintained longer than combat gauze.

Sims K, Montgomery HR, Dituro P, Kheirabadi BS, Butler FK. Management of External Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: The Adjunctive Use of XStat™ Compressed Hemostatic Sponges: TCCC Guidelines Change 15-03. J Spec Oper Med. 2016 Spring;16(1):19-28.

C-EO - Clinical consensus, Expert Opinion & Discussion – TCCC change to include XStat as a CoTCCC-recommended hemostatic adjunct.

Cestero RF, Song BK. The effect of hemostatic dressings in a subclavian artery and vein transection porcine model. Technical Report 2013=012. San Antonio, TX; Naval Medical Research Unit San Antonio; 2013.

Kragh JF, Aden JK. Gauze vs XStat in wound packing for hemorrhage control. Am J Emerg Med. 2015: 974–976.

Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 November 2021, Basic Management Plan for Tactical Field Care para 3.b. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 5 Mar 22.

Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 5 November 2020, Basic Management Plan for Tactical Field Care para 3.b. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 5 Mar 22.

Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 5 November 2020, Basic Management Plan for Tactical Field Care para 3.c. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 5 Mar 22.

Owens BD, JF Kragh Jr, JC Wenke, J Macaitis, CE Wade, JB Holcomb. Combat wounds in operation Iraqi Freedom and operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2008;64(2):295–299.

Phrampus PE, L Walker. Danger zone. The prehospital assessment & treatment of blunt & penetrating neck trauma. JEMS. 2002; 27(11): 26–38.

Tisherman SA, F Bokhari, B Collier, J Cumming, J Ebert, M Holevar, et al. Clinical practice guideline: penetrating zone II neck trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64(5):1392–1405.

Onifer DJ, McKee JL, Faudree LK, Bennett BL, Miles EA, Jacobsen T, Morey JK, Butler FK Jr. Management of Hemorrhage From Craniomaxillofacial Injuries and Penetrating Neck Injury in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: iTClamp Mechanical Wound Closure Device TCCC Guidelines Proposed Change 19-04 06 June 2019. J Spec Oper Med. 2019 Fall;19(3):31-44.

Tan EC, JH Peters, JL McKee, MJ Edwards. The iTClamp in the management of prehospital haemorrhage. Injury. 2016;47(5): 1012–1015.

Shaw GLT. A service evaluation of the iTClamp50 in pre-hospital external haemorrhage control. Br Paramedic J. 2016;1(2): 30–34.

McKee JL, Kirkpatrick AW, Bennett BL, Jenkins DA, Logsetty S, Holcomb JB. Worldwide Case Reports Using the iTClamp for External Hemorrhage Control. J Spec Oper Med. 2018 Fall;18(3):39-44.

Onifer DJ, McKee JL, Faudree LK, Bennett BL, Miles EA, Jacobsen T, Morey JK, Butler FK Jr. Management of Hemorrhage From Craniomaxillofacial Injuries and Penetrating Neck Injury in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: iTClamp Mechanical Wound Closure Device TCCC Guidelines Proposed Change 19-04 06 June 2019. J Spec Oper Med. 2019 Fall;19(3):31-44.

St John AE, X Wang, EB Lim, D Chien, SA Stern, NJ White. Effects of rapid wound sealing on survival and blood loss in a swine model of lethal junctional arterial hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(2): 256–262.

Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith Jr SC. Scientific Evidence Underlying the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Medical Association. 2009 Feb; Vol 301, No. 8.

Halparin, JL. Further Evolution of the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendation Classification System. American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. 2016 Apr; 133:1426-1428.

Evidence Based References:

Altamirano MP, Kragh JF Jr, Aden JK 3rd, Dubick MA. Role of the Windlass in Improvised Tourniquet Use on a Manikin Hemorrhage Model. J Spec Oper Med. 2015 Summer;15(2): 42-6.

C-LD

Bennett BL, et al. Management of External Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: Chitosan-Based Hemostatic Gauze Dressings--TCCC Guidelines-Change 13-05. J Spec Oper Med. 2014 Fall;14(3): 40-57.

C-LD

Bennett BL. Bleeding Control Using Hemostatic Dressings: Lessons Learned. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017 Jun;28(2S): S39-S49.

C-LD

Bennett BL. Bleeding Control Using Hemostatic Dressings: Lessons Learned. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017 Jun;28(2S): S39-S49.

C-LD

Blackbourne LH, Baer DG, Eastridge BJ, et al. Military medical revolution: prehospital combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73: S372–S377.

C-EO

Bulger EM, Snyder D, Schoelles K, et al. An evidence-based prehospital guideline for external hemorrhage control: American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18(2): 163-173. C-LD

Butler FK Jr, Hagmann J, Butler EG. Tactical combat casualty care in special operations. Mil Med. 1996 Aug;161 Suppl:3-16.

C-EO

Cestero RF, Song BK. The effect of hemostatic dressings in a subclavian artery and vein transection porcine model. Technical Report 2013=012. San Antonio, TX; Naval Medical Research Unit San Antonio; 2013.

C-LD

Charlton NP, et al. Control of Severe, Life-Threatening External Bleeding in the Out-of-Hospital Setting: A Systematic Review. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021 Mar-Apr;25(2):235-267.

B-NR

Croushorn J, Thomas G, McCord SR. Abdominal aortic tourniquet controls junctional hemorrhage from a gunshot wound of the axilla. J Spec Oper Med. 2013 Fall;13(3):1-4.

C-LD

David M, Gogi N, Rao J, Selzer G. The art and rationale of applying a compression dressing. Br J Nurs. 2010 Feb 25-Mar 10;19(4):235-6.

C-EO

Dory R, Cox D, Endler B. Test and Evaluation of Compression Bandages. Naval Medical Research Unit San Antonio. NAMRU-SA REPORT #2014-52. Available at https://persysmedical.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/NAMRU-SA-Compression-Bandages-TR.pdf; accessed 2 Mar 2022.

C-LD