TCCC Summary of Supporting Evidence

JTS/CoTCCC

Understanding Combat Casualty Care Statistics

John B. Holcomb, MD, Lynn G. Stansbury, MD, Howard R. Champion, FRCS, Charles Wade, PhD, and Ronald F. Bellamy, MD

The Journal of TRAUMA, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

J Trauma. 2006;60:397?401.

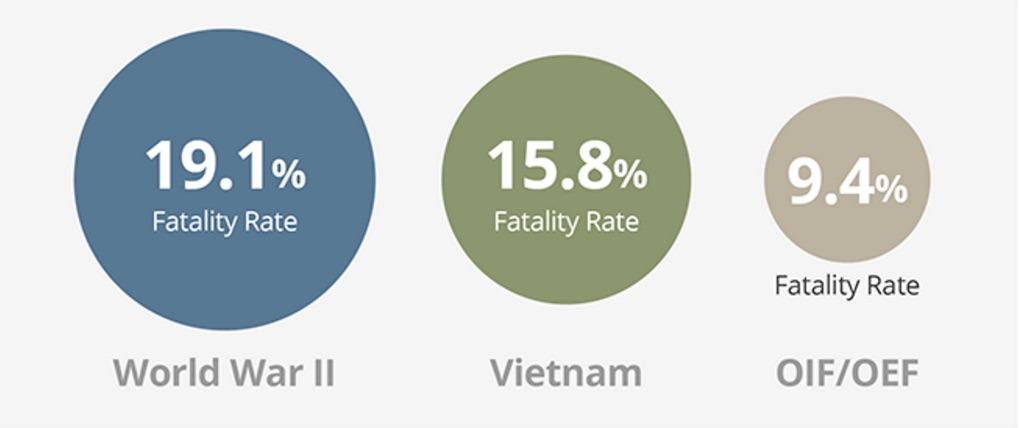

The objective of this paper was to develop standardized terminology and equations that produce the best insight into the effectiveness of care at different stages of treatment. These equations were then applied consistently across data from the WWII, Vietnam and the current Global War on Terrorism (OIF/OEF). Three essential terms were clarified:

- the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) as percentage of fatalities among all wounded

- Killed in Action (KIA) as percentage of immediate deaths among all seriously injured (not returning to duty)

- Died of Wounds (DOW) as percentage of deaths following admission to a medical treatment facility among all seriously injured (not returning to duty).

Using this clear set of definitions, the equations were used to ask two basic questions:

- What is the overall lethality of the battlefield?

- How effective is combat casualty care?

Take Home Message:

Based on a comparison of statistics for battle casualties from 1941-2005, the U.S. casualty survival rate in Iraq and Afghanistan has been the best in U.S. history.

Why Are We Doing Better?

- Improved Personal Protective Equipment

- Tactical Combat Casualty Care

- Faster evacuation time

- Better trained medics

Death on the Battlefield (2001- 2011): Implications for the future of combat casualty care

Brian J. Eastridge, MD, Robert L. Mabry, MD, Peter Seguin, MD, Joyce Cantrell, MD, Terrill Tops, MD, Paul Uribe, MD, Olga Mallett, Tamara Zubko, Lynne Oetjen-Gerdes, Todd E. Rasmussen, MD, Frank K. Butler, MD, Russell S. Kotwal, MD, John B. Holcomb, MD, Charles Wade, PhD, Howard Champion, MD, Mimi Lawnick, Leon Moores, MD, and Lorne H. Blackbourne, MD

The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery

J Trauma Acute Care Surg, Volume 73, Number 6, Supplement 5

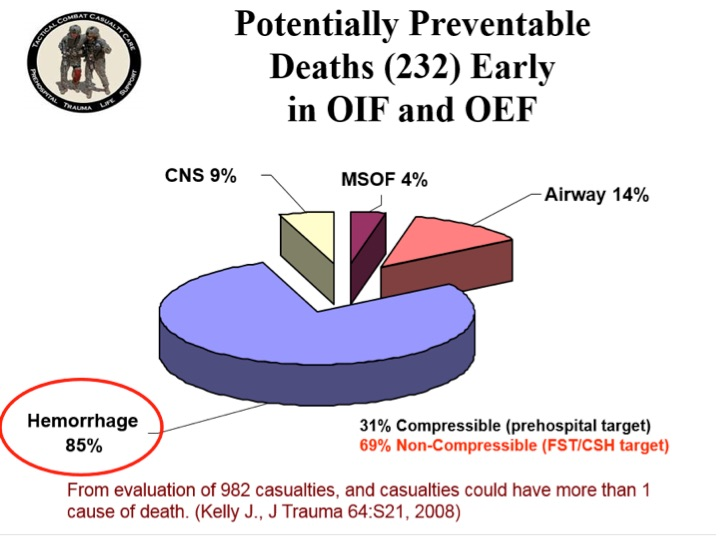

Most battlefield casualties died of their injuries before ever reaching a surgeon. As most pre-medical treatment facility (pre-MTF) deaths are nonsurvivable, mitigation strategies to impact outcomes in this population need to be directed toward injury prevention. To significantly impact the outcome of combat casualties with potentially survivable (PS) injury, strategies must be developed to mitigate hemorrhage and optimize airway management or reduce the time interval between the battlefield point of injury and surgical intervention.

Understanding battlefield mortality is a vital component of the military trauma system. Emphasis on this analysis should be placed on trauma system optimization, evidence-based improvements in Tactical Combat Casualty Care guidelines, data-driven research, and development to remediate gaps in care and relevant training and equipment enhancements that will increase the survivability of the fighting force.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

A Profile of Combat Injury

Howard R. Champion, FRCS(Edin), FACS, Ronald F. Bellamy, MD, FACS, COL, US Army, Ret., Colonel P. Roberts, MBE, QHS, MS, FRCS, L/RAMC, and Ari Leppaniemi, MD, PhD

The Journal of TRAUMA, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

J Trauma. 2003;54:S13?S19.

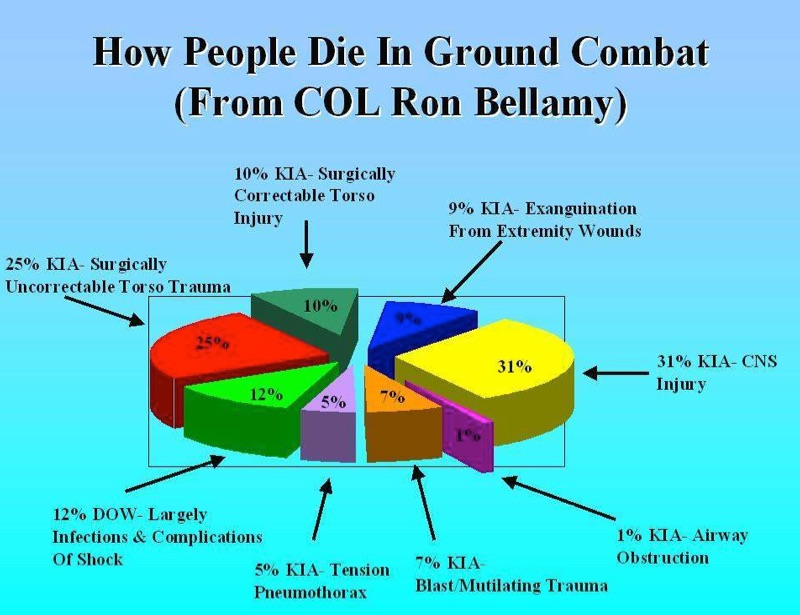

Traumatic combat injuries differ from those encountered in the civilian setting in terms of epidemiology, mechanism of wounding, pathophysiologic trajectory after injury, and outcome. Except for a few notable exceptions, data sources for combat injuries have historically been inadequate. Although the pathophysiologic process of dying is the same (i.e., dominated by exsanguination and central nervous system injury) in both the civilian and military arenas, combat trauma has unique considerations with regard to acute resuscitation, including (1) the high energy and high lethality of wounding agents; (2) multiple causes of wounding; (3) preponderance of penetrating injury; (4) persistence of threat in tactical settings; (5) austere, resource-constrained environment; and (5) delayed access to definitive care. Recognition of these differences can help bring focus to resuscitation research for combat settings and can serve to foster greater civilian-military collaboration in both basic and transitional research.

Take Home Message:

Injury Severity and Causes of Death From Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom: 2003-2004 versus 2006

Joseph F. Kelly, MD, Amber E. Ritenour, MD, Daniel F. McLaughlin, MD, Karen A. Bagg, MS, Amy N. Apodaca, MS, Craig T. Mallak, MD, Lisa Pearse, MD, Mary M. Lawnick, RN, BSN, Howard R. Champion, MD, Charles E. Wade, PhD, and COL John B. Holcomb, MC

The Journal of TRAUMA, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

J Trauma. 2008;64:S21?S27.

The opinion that injuries sustained in Iraq and Afghanistan have increased in severity is widely held by clinicians who have deployed multiple times. To continuously improve combat casualty care, the Department of Defense has enacted numerous evidence-based policies and clinical practice guidelines. Overall causes of death were examined, looking for opportunities of improvement for research and training.

In the time periods of the war studied, deaths per month has doubled, with increases in both injury severity and number of wounds per casualty. Truncal hemorrhage is the leading cause of potentially survivable deaths. Arguably, the success of the medical improvements during this war has served to maintain the lowest case fatality rate on record.

Take Home Message:

Survival with Emergency Tourniquet Use

COL John F. Kragh, Jr., MC, USA, Thomas J. Walters, PhD, David G. Baer, PhD, LTC Charles J. Fox, MC, USA, Charles E. Wade, PhD, Jose Salinas, PhD, and COL John B. Holcomb, MC, USA

Annals of Surgery

Volume 249, Number 1, January 2009

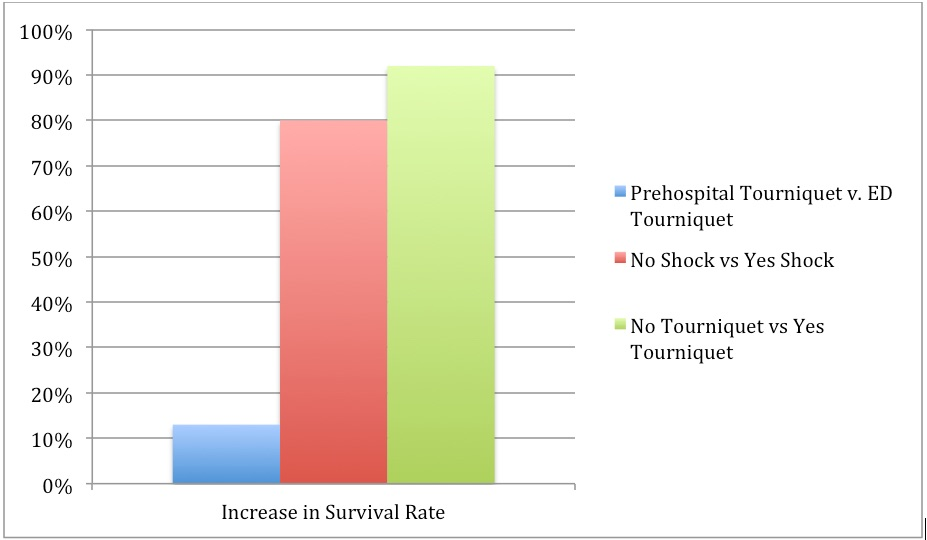

The purpose of this study at a combat support hospital in Baghdad was to determine if emergency tourniquet use saved lives.

- Tourniquets are saving lives on the battlefield.

- Improved survival when tourniquets were applied BEFORE casualties went into shock.

- 31 lives saved in this study by applying tourniquets prehospital rather than in the ED.

- In 5 casualties where a tourniquet was indicated but not used, there was a survival rate of 0% versus 87% for those casualties with tourniquet applications.

Increase in survival rate by tourniquet use. By breaking down, the tourniquet use by whether the patient was prehospital or ED, whether there was shock present or absent at the time of application, and whether tourniquets were used or not, a comparison of raw differences in survival rates indicates that the survival benefit to tourniquet use is more strongly related to tourniquet use before the patient has progressed to shock than to prehospital use.

Take Home Message:

Practical Use of Emergency Tourniquets

John F. Kragh, Jr., MD, Thomas J. Walters, PhD, David G. Baer, PhD, Charles J. Fox, MD, Charles E. Wade, PhD, Jose Salinas, PhD, and COL John B. Holcomb, MC

The Journal of TRAUMA, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

J Trauma. 2008;64:S38 ?S50

Few studies describe the actual morbidity associated with tourniquet use in combat casualties. The purpose of this study was to measure tourniquet use and subsequent complications. A prospective survey of casualties who required tourniquets was performed at a combat support hospital in Baghdad during 7 months in 2006. Patients were evaluated for tourniquet use, limb outcome, and morbidity.

- 232 patients with tourniquets on 309 limbs

- CAT was the best field tourniquet

- Approximately 3% had transient nerve palsies

- NO amputations caused by tourniquet use

Take Home Message:

Studies on the Efficacy of Hemostatic Agents

Hemorrhage Control Studies:

Management of External Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: The Adjunctive Use of XStat? Compressed Hemostatic Sponges. TCCC Guidelines: Change 15-03.

Kyle Sims; F. Bowling, Harold Montgomery, Paul Dituro; Bijan S. Kheirabadi, PhD, Frank Butler, MD

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

J Spec Oper Med. 2016 Spring;16(1):19-28

Management of External Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: Chitosan-Based Hemostatic Gauze Dressings. TCCC Guidelines ? Change 13-05.

Brad L. Bennett, PhD, NREMT-P; Lanny F. Littlejohn, MD; Bijan S. Kheirabadi, PhD;

Frank K. Butler, MD; Russ S. Kotwal, MD; Michael A. Dubick, PhD; Jeffrey A. Bailey, MD

Journal of Special Operations Medicine

J Spec Oper Med. 2014 Fall;14(3):40-57

Comparison of novel hemostatic gauzes to QuikClot Combat Gauze in a standardized swine model of uncontrolled hemorrhage.

Jason M. Rall, PhD, Jennifer M. Cox, BS, Adam G. Songer, MD, Ramon F. Cestero, MD,

and James D. Ross, PhD

Journal of Trauma Acute Care Surgery

J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013; 75(2 Suppl 2):S150-6.

Hemostasis in a noncompressible hemorrhage model: An end-user evaluation of hemostatic agents in a proximal arterial injury.

Steven Satterly, MD, Daniel Nelson, DO, Nathan Zwintscher, MD, Morohunranti Oguntoye, MD, Wayne Causey, MD, Bryan Theis, BS, Raywin Huang, PhD, Mohamad Haque, MD,

Matthew Martin, MD, J Gerald Bickett EMT, and Robert M. Rush Jr, MD

Journal of Surgical Education

J Surg Educ. 2013;70(2):206-11.

Advanced hemostatic dressings are not superior to gauze for care under fire scenarios.

Jennifer M. Watters, MD, Philbert Y. Van, MD, Gregory J. Hamilton, BS, Chitra Sambasivan, MD, Jerome A. Differding, MPH, and Martin A. Schreiber, MD

Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

J Trauma 2011;70:1413-18.

Comparison of two packable hemostatic Gauze dressings in a porcine hemorrhage model.

Richard Bruce Schwartz MD, Bradford Zahner Reynolds MD, Stephen A. Shiver MD, E. Brooke Lerner PhD, Eric Mark Greenfield DO, Ricaurte A. Solis DO, Nicholas A. Kimpel DO, Phillip L. Coule MD & John G. McManus MD

Prehospital Emergency Care

Prehosp Emerg Care 2011;15:477-482

A synthesis of studies performed to evaluate the efficacy of the various hemostatic agents available at the point of injury show that they all perform equally.

Novel hemostatic devices (QuikClot Combat Gauze, QuikClot Combat Gauze XL, Celox Trauma Gauze, Celox Gauze, or HemCon ChitoGauze) perform at least as well as the current Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care standard for point-of-injury hemorrhage control. Despite their different compositions and sizes, the lack of clear superiority of any agent suggests that contemporary hemostatic dressing technology has potentially reached a plateau for efficacy.

There is no significant difference in hemostasis between hemostatic bandages for proximal arterial hemorrhage. Hemostasis significantly improves between 2 and 4 minutes using direct pressure and hemostatic agents. Prior medical training leads to 20% greater efficacy when using hemostatic dressings.

ChitoGauze and CombatGauze appear to be equally efficacious in their hemostatic properties, as demonstrated in a porcine hemorrhage model.

XStat (a non-absorbable, expandable, hemostatic sponge) is a new product recently approved by the FDA as a hemostatic adjunct to aid in the control of bleeding from junctional wounds in the groin or axilla. XStat is a new option for the control of external hemorrhage from junctional bleeding sites that are not adequately addressed by tourniquets, Combat gauze, Celox gauze, Chitogauze, Combat Ready Clamp, Junctional Emergency Treatment Tool, or the SAM Junctional Tourniquet.

Take Home Message:

READ FULL PDF

READ FULL PDF

READ FULL PDF

Immediate versus Delayed Fluid RES for Hypotensive Patients with Penetrating Torso Injuries

William H. Bickell, MD., Matthew J. Wall, Jr., M.D., Paul E. Pepe, MD., R. Russell Martin, MD., Victoria F. Ginger, MSN., Mary K. Allen, BA., and Kenneth L. Mattox, MD.

The New England Journal of Medicine 2012;331(17):1105-1109.

Fluid resuscitation may be detrimental when given before bleeding is controlled in patients with trauma. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of delaying fluid resuscitation until the time of operative intervention in hypotensive patients with penetrating injuries to the torso.

This was a prospective trial comparing immediate and delayed fluid resuscitation in 598 adults with penetrating torso injuries who presented with a prehospital systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg. Patients assigned to the immediate-resuscitation group received standard fluid resuscitation before they reached the hospital and in the trauma center, and those assigned to the delayed-resuscitation group received intravenous cannulation but no fluid resuscitation until they reached the operating room.

Among the 289 patients who received delayed fluid resuscitation, 203 (70%) survived and were discharged from the hospital, as compared with 193 of the 309 patients (62%) who received immediate fluid resuscitation. The mean estimated intraoperative blood loss was similar in the two groups. Among the 238 patients in the delayed-resuscitation group who survived to the postoperative period, 55 (23%) had one or more complications (adult respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis syndrome, acute renal failure, coagulopathy, wound infection, and pneumonia), as compared with 69 of the 227 patients (30%) in the immediate-resuscitation group. The duration of hospitalization was shorter in the delayed-resuscitation group.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

Military Application of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma Emergency Resuscitation (MATTERs) Study

Jonathan J. Morrison, MB ChB, MRCS; Joseph J. Dubose, MD; Todd E. Rasmussen, MD; Mark J. Midwinter, BMedSci, MD, FRCS

Archives of Surgery 2012;147(2):113-119.

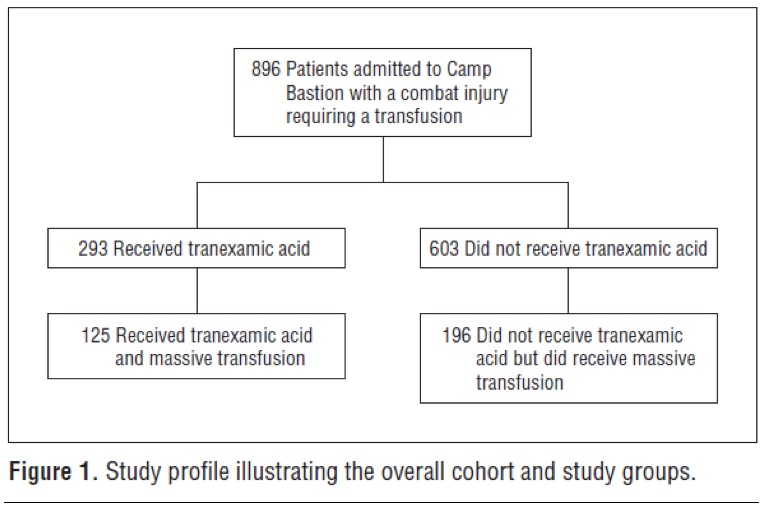

The purpose of this study was to characterize contemporary use of tranexamic acid (TXA) in combat injury and to assess the effect of its administration on total blood product use, thromboembolic complications, and mortality. This was a retrospective observational study comparing TXA administration with no TXA in patients receiving at least 1 unit of packed red blood cells. A subgroup of patients receiving massive transfusion (greater than 10 units of packed red blood cells) was also examined.

A total of 896 consecutive combat injury admissions to a Role 3 Echelon surgical hospital in southern Afghanistan were evaluated (of the 896 injured patients, 293 received TXA). Outcome measures included mortality at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 30 days as well as the influence of TXA administration on postoperative coagulopathy and the rate of thromboembolic complications.

The TXA group had lower unadjusted mortality than the no-TXA group (17.4% vs 23.9%, respectively) despite being more severely injured. This benefit was greatest in the group of patients who received massive transfusion , where TXA was also independently associated with survival and less coagulopathy.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

Mechanism of Action of Tranexamic Acid in Bleeding Trauma Patients

Ian Roberts, David Prieto-Merino and Daniela Manno

Critical Care 2014, 18:685

To investigate the mechanism of action of tranexamic acid (TXA) in bleeding trauma patients, the authors examined the timing of its effect on mortality. The working hypothesis was the following-- if TXA reduces mortality by decreasing blood loss, its effect should be greatest on the day of the injury when bleeding is most profuse. However, if TXA reduces mortality via an anti-inflammatory mechanism its effect should be greater over the subsequent days. This paper is an exploratory analysis, including per-protocol analyses, of data from the CRASH-2 trial, a randomized placebo controlled trial of the effect of TXA on mortality in 20,211 trauma patients with, or at risk of, significant bleeding.

The effect of TXA on mortality is greatest for deaths occurring on the day of the injury. This survival benefit is only evident in patients in whom treatment is initiated within 3 hours of their injury. Initiation of TXA treatment within 3 hours of injury reduced the hazard of death due to bleeding on the day of the injury by 28%. TXA treatment initiated beyond 3 hours of injury appeared to increase the hazard of death due to bleeding, although the estimates were imprecise. Early administration of tranexamic acid appears to reduce mortality primarily by preventing exsanguination on the day of the injury.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

Eliminating Preventable Death on the Battlefield

Russ S. Kotwal, MD, MPH; Harold R. Montgomery, NREMT; Bari M. Kotwal, MS; Howard R. Champion, FRCS; Frank K. Butler Jr, MD; Robert L. Mabry, MD; Jeffrey S. Cain, MD; Lorne H. Blackbourne, MD; Kathy K. Mechler, MS, RN; John B. Holcomb, MD

Archives of Surgery 2011;146(12):1350-1358

The objective of this paper was to evaluate battlefield survival in a novel command-directed casualty response system that comprehensively integrates Tactical Combat Casualty Care guidelines and a prehospital trauma registry. Information was obtained via an analysis of battle injury data collected from the 75th Ranger Regiment, US Army Special Operations Command during combat deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq from October 1, 2001 through March 31, 2010. Casualties were scrutinized for preventable adverse outcomes and opportunities to improve care. Comparisons were made with Department of Defense casualty data for the military as a whole.

A total of 419 battle injury casualties were incurred during 7 years of continuous combat in Iraq and 8.5 years in Afghanistan. Despite higher casualty severity indicated by return-to-duty rates, the regiment’s rates of 10.7% killed in action and 1.7% who died of wounds were lower than the Department of Defense rates of 16.4% and 5.8%, respectively, for the larger US military population. Of 32 fatalities incurred by the regiment, none died of wounds from infection, none were potentially survivable through additional prehospital medical intervention, and 1 was potentially survivable in the hospital setting. Substantial prehospital care was provided by nonmedical personnel.

Take Home Message:

US Rangers in Somalia: An Analysis of Combat Casualties on an Urban Battlefield

Robert L. Mabry, MD, John B. Holcomb, MD, Andrew M. Baker, MD, Clifford C. Cloonan, MD, John M. Uhorchak, MD, Denver E. Perkins, MD, Anthony J. Canfield, MD, and John H. Hagmann, MD

The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 2000, Volume 49(3)

This study was undertaken to determine the differences in injury patterns between soldiers equipped with modern body armor in an urban environment compared with the soldiers of the Vietnam War. From July1998 to March 1999, data were collected for a retrospective analysis on all combat casualties sustained by United States military forces in Mogadishu,Somalia, on October 3 and 4, 1993. This was the largest and most recent urban battle involving United States ground forces since the Vietnam War.

There were 125 combat casualties. Casualty distribution was similar to that of Vietnam; 11% died on the battlefield, 3% died after reaching a medical facility, 47% were evacuated, and 39% returned to duty. No missiles penetrated the solid armor plate protecting the combatants’ anterior chests and upper abdomens. Most fatal penetrating injuries were caused by missiles entering through areas not protected by body armor, such as the face, neck, pelvis, and groin. Three patients with penetrating abdominal wounds died from exsanguination, and two of these three died after damage-control procedures.

At the time of this study, United States Army doctrine on prehospital care did not include antibiotic administration by medics in the field. Information on field use of antibiotics in this battle is only anecdotal, but it seems that very few of the casualties received antibiotics before reaching a casualty collection point or hospital. Early administration of antibiotics to combat casualties is recommended in many studies. The NATO Emergency War Surgery Handbook suggests that parenteral antibiotics be given as early as possible to all patients with penetrating abdominal injuries, open comminuted fractures, and extensive soft-tissue extremity wounds. Because evacuation to definitive surgical care is likely to be delayed more than 6 hours in future urban conflicts, antibiotic therapy should be initiated by medics in the field, preferably within the first hour of injury.

Take Home Message:

Analysis of Battlefield Cricothyroidotomy in Iraq and Afghanistan

Robert L. Mary, MD; Alan Frankfurt, MD

The Journal of Special Operations Medicine

J Spec Oper Med. 2012 Spring;12(1):17-23.

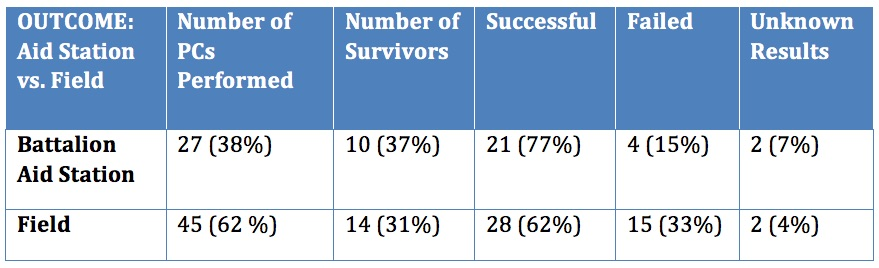

Historical review of modern military conflicts suggests that airway compromise accounts or 1-2 % of total combat fatalities. This study examines the specific intervention of pre-hospital cricothyrotomy (PC) in the military setting using the largest studies of civilian medics performing PC as historical controls.

The majority of patients who underwent PC died (66%). The largest group of survivors had gunshot wounds to the face and/or neck (38%) followed by explosion related injury to the face, neck and head (33%). Military medics have a 33% failure rate when performing this procedure compared to 15% for physicians and physician assistants. Minor complications occurred in 21 % of cases. The survival rate and complication rates are similar to previous civilian studies of medics performing PC. However, the failure rate for military medics is three to five times higher than comparable civilian studies.

Take Home Message:

Comparison of Two Open Surgical Cricothyroidotomy Techniques by Medics using a Cadaver Model

Robert L. Mabry, MD; Matthew C. Nichols, DO; Drew C. Shiner, MD; Scotty Bolleter, BS, EMT-P; Alan Frankfurt, MD

Annals of Emergency Medicine

Ann Emerg Med. 2014 Jan;63(1):1-5.

The CricKey is a novel surgical cricothyroidotomy device combining the functions of a tracheal hook, stylet, dilator, and bougie incorporated with a Melker airway cannula. This study compares surgical cricothyroidotomy with standard open surgical versus CricKey technique.

Participants included US Army combat medics credentialed at the emergency medical technician–basic level. After a brief anatomy review and demonstration, 15 military medics with minimal training performed in random order standard open surgical cricothyroidotomy and CricKey surgical cricothyroidotomy on cadavers. Compared with the standard open surgical cricothyroidotomy technique, military medics demonstrated faster insertion with the CricKey. First-pass success was not significantly different between the techniques.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

Chest Wall Thickness in Military Personnel: Implications for Needle Thoracentesis in Tension Pnemothorax

COL H. Theodore Harcke, MC USA, COL H. Theodore Harcke, MC USA; LCDR Lisa A. Pearse, MC USN; COL Angela D. Levy, MC USA; John M. Getz, BS; CAPT Stephen R. Robinson, MC USN

Military Medicine, Vol. 172, December 2007

Advanced Trauma Life Support guidelines and combat casualty care doctrine recommend the use of needle thoracentesis (needle thoracostomy) for the emergency treatment of tension pneumothorax. Emergency situations require a reproducible, simple, and effective normal response for treatment of life-threatening pneumothorax. This study evaluated chest wall thickness in a forward-deployed tri-service population using a retrospective analysis of multidetector CT (MDCT)-assisted autopsies performed on combat casualties at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

If needle thoracentesis is attempted with an angiocatheter or needle of insufficient length, the procedure will fail. Recommended procedures for needle thoracentesis to relieve tension pneumothorax should be adapted to reflect use of an angiocatheter or needle of sufficient length. A 3.25 inch angiocatheter would have reached the pleural space in 99% of the cases in this series.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

Antibiotics in Tactical Combat Casualty Care 2002

MAJ Kevin O'Connor, MC USA; CAPT Frank Butler, MC USN

Military Medicine. 168. 11:911. 2003

Care of casualties in the tactical combat environment should include the use of prophylactic antibiotics for all open wounds. This article recommends that oral gatifloxacin should be the antibiotic of choice because of its ease of carriage and administration, excellent spectrum of action and relatively mild side effect profile. Moxifloxacin and gatifloxacinare both fourth-generation fluoroquinolones that have an enhanced spectrum of activity and are given as a single daily 400-mg dose. Based on their similarities, eithermoxifloxacin or gatifloxacin would be a good choice for an oral antibiotic to use on the battlefield. Since gatifloxacin was removed from the market by the FDA in 2008, moxifloxacin is the oral antibiotic of choice for battlefield casualties with open wounds.

For those casualties unable to take oral antibiotics because of unconsciousness, penetrating abdominal trauma, or shock, intravenous cefotetan is recommended because of its longer duration of action than cefoxitin. Whereas cefoxitin and cefotetan appear to be equal in efficacy, the longer half-life and comparable cost make cefotetan a better choice for use by combat corpsmen and medics. Cefoxitin remains a viable alternative and a good second choice.

Take Home Message:

Tactical Combat Casualty Care in Operation Iraqi Freedom

CPT Michael J. Tarpey, MC, USA

Army Medical Department Journal, 2005, PB 8-05-4/5/6 Apr/May/Jun

At the time this article was written, the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines had been widely practiced with excellent results throughout the SpecialOperations community. However, there had been very little spread of the use of the TCCC guidelines into conventional units. This article reviews the use of the principles of TCCC by a mechanized infantry unit in Operation Iraqi Freedom1 One (OIF I).

Antibiotics were administered to all casualties with open wounds, even relatively minor fragmentation wounds. None of the casualties developed wound infections. The exact antibiotics recommended in the TCCC guidelines could not be obtained, but suitable alternatives were found. Soldiers who could take oral medicines received Levofloxacin, which was convenient due to its once daily dosing. Those wounded who could not take medicines orally received IV Cefazolin for extremity wounds and lV Ceftriaxone for abdominal injuries.

Take Home Message:

TCCC in the Canadian Forces: Lessons Learned from the Afghan War

LCol Erin Savage, MD, Maj Colleen Forestier, MD, LCol Nicholas Withers, MD, Col Homer Tien, OMM CD, MD, MSc, Capt Dylan Pannell, MD, PhD

Canadian Journal of Surgery 2011;59:S118-S123

In the 6 years that the Canadian Forces (CF) have been involved in sustained combat operations in Kandahar, Afghanistan, more than 1000 CF members have been injured and more than 150 have been killed. As a result, the CF gained substantial experience delivering TCCC to wounded soldiers on the battlefield. The purpose of this paper is to review the principles of TCCC and some of the lessons learned about battlefield trauma care during this conflict.

For the first time in decades, the CF has been involved in a war in which its members have participated in sustained combat operations and have suffered increasingly severe injuries. Despite this, the CF experienced the highest casualty survival rate in history. Though this success is multifactorial, the determination and resolve of CF leadership to develop and deliver comprehensive, multileveled TCCC packages to soldiers and medics is a significant reason for that and has unquestionably saved the lives of Canadian, Coalition and Afghan Security Forces.

Take Home Message:

Prehospital Traumatic Cardiac Arrest: The Cost of Futility

Alexander S. Rosemurgy, MD, P. A. Norris, MSN, S. M. Olson, RN, J. M. Hurst, MD, and M. H. Albrink, MD

The Journal of Trauma, Volume 35(3)

This study reviewed records for 12,462 trauma patients cared for by prehospital services from October 1, 1989 to March 31, 1991. Out of the total number of patients, 138 underwent CPR at the scene or during transport because of the absence of blood pressure, pulse, and respiration. Ninety-six (70%) suffered blunt trauma, 42 (30%) suffered penetrating trauma. Sixty (43%) were transported by air utilizing county-wide transport protocols. None of the patients survived.

Trauma patients who require CPR at the scene or in transport die. Infrequent organ procurement does not seem to justify the cost (primarily borne by hospitals), consumption of resources, and exposure of health care providers to occupational health hazards. The wisdom of transporting trauma victims suffering cardiopulmonary arrest at the scene or during transport must be questioned. Allocation of resources to these patients is not an insular medical issue, but a broad concern for our society, and society should decide if the "cost of futility" is excessive.

Take Home Message:

The Use of Pelvic Binders in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 1602

Col Stacy Shackelford, MD; Rick Hammesfahr, MD; MSG (Ret); MSG Daniel Morissette, SO-ATP; Harold Montgomery, SO-ATP; Win Kerr, SO-ATP; CAPT (Ret) Brad Bennett, PhD, NREMT-P; Col (Ret) Warren Dorlac, MD; CAPT Stephen Bree, MD; CAPT (Ret) Frank Butler, MD

Journal of Special Operation Medicine 2017 (1) 135-147

Pelvic fractures can result in massive bleeding and death. Dismounted improvised explosive device (IED) attacks, gunshot wounds and motor vehicle accidents often result in pelvic fractures. IED attacks have been the major cause of combat related injuries during the Afghanistan conflict. “Twenty-six percent of service members who died during Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom had a pelvic fracture.” For these reasons, the CoTCCC conducted an extensive review of the literature which led to the addition of pelvic binders to the TCCC guidelines.

• Emergent treatment options for pelvic fractures include pelvic binder, external fixation, internal fixation, direct surgical hemostasis, preperitoneal pelvic packing, and pelvic angiography and embolization. Of these, the only treatment available to prehospital providers is the pelvic binder.

• Although definitive evidence demonstrating improved survival with pelvic binder use is lacking, the existing evidence addressing the management of pelvic hemorrhage recommends pelvic binder use for initial management of pelvic fracture hemorrhage.

• Placement of the binder at the level of the pubic symphysis and greater trochanters was shown to reduce the unstable pelvic fracture most effectively with the least amount of force.

• It is more likely that splinting of pathologic fracture motion allows clot formation and is the mechanism that aids in hemostasis.

• Hemorrhage with stable fracture patterns is unlikely to be controlled with a pelvic binder. However, since it is not possible to differentiate a stable from an unstable fracture pattern in the prehospital environment, all suspected pelvic fractures should have a binder applied.

• Applying a pelvic binder is unlikely to increase injury or bleeding. Prolonged use or overtightening may cause pressure ulcerations.

• A pelvic binder should be applied for cases of suspected pelvic fracture in severe blunt force or blast injury with one or more of the following indications:

- Pelvic pain

- Any major lower limb amputation or near amputation

- Physical exam findings suggestive of a pelvic fracture

- Unconsciousness

- Shock

• There is very weak evidence to suggest that a commercial device is more effective in controlling hemorrhage than an improvised sheet. There is no evidence that any commercial compression device is better than another.

Take Home Message:

Fluid Resuscitation for Hemorrhagic Shock in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 14-01 - 2 June 2014

Frank K. Butler, MD; John 8. Holcomb, MD; Martin A. Schreiber, MD; Russ S. Kotwal, MD; Donald A. Jenkins, MD; Howard R. Champion, MD, FACS, FRCS; F. Bowling; Andrew P. Cap, MD; Joseph J. Dubose, MD; Warren C. Dorlac, MD; Gina R. Dorlac, MD; Norman E. McSwain, MD, FACS; Jeffrey W Timby, MD; Lorne H. Blackbourne, MD; Zsolt T. Stockinger, MD; Geir Strandenes, MD; Richard B, Weiskopf, MD; Kirby R. Gross, MD; Jeffrey A. Bailey, MD

Journal of Special Operations Medicine. 2014 Fall;14(3):13-38.

This article discusses changes in the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines that are based on a review of the literature on fluid resuscitation in hemorrhagic shock. The evidence extracted from the literature review was applied to the resuscitation of combat casualties in the prehospital environment and used to develop updated TCCC fluid resuscitation guidelines.

Order of precedence for resuscitation fluid options:

- Whole blood

- 1:1:1 plasma, Red Blood Cells (RBCs), and platelets

- 1:1 plasma and RBCs

- Reconstituted Dried Plasma, liquid plasma, or thawed plasma alone or RBCs alone

- Hextend

- LR or Plasma-Lyte A

* *Normal Saline (NS) is not recommended for hemorrhagic shock, but may be indicated for dehydration.

- Dried plasma (DP) is added as an option when other blood components or whole blood are not available

- Hextend is a less desirable option than whole blood, blood components, or DP and should be used only when these preferred options are not available

- 1: 1: 1 damage control resuscitation (DCR) is preferred to 1:1 DCR when platelets arc available as well as plasma and red cells;

- The 30-minute wait between increments of resuscitation fluid administered to achieve clinical improvement or target blood pressure (BP) has been eliminated.

- The volume of fluid used in the resuscitation of casualties in hemorrhagic shock is an important factor in determining outcomes. The optimal volume may vary based on the type of injuries present, but large-volume crystalloid fluid resuscitation for patients in shock caused by penetrating torso trauma has been shown to decrease patient survival compared with resuscitation with restricted volumes of crystalloid.

- Hextend may decrease complications of crystalloid resuscitation such as ARDS and ACS, but does not decrease the dilutional coagulopathy caused by crystalloid resuscitation.

Take Home Message:

Emergency Whole-blood use in the Field: A Simplified Protocol for Collection and Transfusion

Geir Strandenes, Marc De Pasquale, Andrew P. Cap, Tor A. Hervig, Einar K. Kristoffersen, Matthew Hickey, Christopher Cordova, Olle Berseus

SHOCK, Vol. 41, Supplement 1, pp. 76Y83, 2014

Combat medics need proper protocol-based guidance and education if whole-blood collection and transfusion are to be successfully and safely performed in austere environments. This article presents the Norwegian Naval Special Operation Commando unit specific remote damage control resuscitation protocol, which includes field collection and transfusion of whole blood as an example that can be used be used as a template to develop unit specific protocols.

- Resuscitation in the field with a full complement of RBCs, plasma, and platelets may offer an advantage, especially under conditions where evacuation is delayed.

- No current evacuation system, military or civilian, can provide RBC, plasma, and platelet units in a prehospital environment, especially in austere settings.

- Military experience and laboratory data provide a rationale for whole-blood use in the treatment of massive hemorrhage

- As a result, for the vast majority of casualties, in austere settings, with life-threatening hemorrhage, it is appropriate to consider a whole blood based resuscitation approach to reduce the risk of death from hemorrhagic shock.

Take Home Message:

Warm Fresh Whole Blood is Independently Associated with Improved Survival for Patients with Combat-Related Traumatic Injuries

Philip C. Spinella, MD, Jeremy G. Perkins, MD, Kurt W. Grathwohl, MD, Alec C. Beekley, MD, and John B. Holcomb, MD

The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

J Trauma. 2009;66:S69 ?S76.

The authors of this article examined the possibility that warm fresh whole blood (WFWB) transfusion would be associated with improved survival in patients with traumatic injuries compared with those transfused only stored component therapy (CT). They retrospectively looked at US Military combat casualty patients transfused >1 unit of red blood cells (RBCs), and compared two groups of patients:

- WFWB, who were transfused WFWB, RBCs, and plasma but not apheresis platelets

- CT, who were transfused RBC, plasma, and apheresis platelets but not WFWB.

The primary outcomes measured were 24-hour and 30-day survival. Of 354 patients analyzed there were 100 in the WFWB and 254 in the CT group. Patients in both groups had similar severity of injury.

- Both 24-hour and 30-day survival were higher in the WFWB cohort compared with CT patients.

- An increased amount (825 mL) of additives and anticoagulants were administered to the CT compared with the WFWB group.

- Upon further statistical analysis, the use of WFWB and the volume of WFWB transfused was independently associated with improved 30-day survival.

- In a subset analysis, the data indicated that as time progressed and capabilities improved at combat support hospitals that the relationship between improved survival and WFWB use remained and was not influenced by this factor.