Hypothermia: Prevention and Treatment

Joint Trauma System

Hypothermia: Prevention & Treatment

Summary of Changes

- Incorporates Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Guidelines for Hypothermia from 2021.

- Expands prevention of trauma-induced hypothermia to include not only trauma patients in hemorrhagic shock, but also burns and cerebrospinal injuries.

- Outlines characteristics of hypothermia prevention and treatment systems that can be utilized in addition to the more widely used system, the Hypothermia Prevention and Management Kit (HPMK) and the Heat Reflective Shell (HRS).

- Provides option if unable to remove wet clothing to include the enclosure of the casualty with a vapor barrier over the wet clothing.

- Recommends upgrading the HPMK to an insulated system as soon as possible as it is non-insulated and therefore only suitable for short term hypothermia prevention.

- Provides specific target for warm resuscitation fluids/blood products to 38-42 degrees Celsius.

- Adds Prolonged Casualty Care (PCC) guidelines to the CPG.

- Expands Field Expedient ‘Tricks of the Trade’ in the CPG.

BACKGROUND

Hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis are the physiological derangements constituting the “triad of death” in trauma patients.1–4 Here, we use the term trauma-induced hypothermia (TIH) as it relates more specifically to combat trauma including hemorrhagic shock, cerebrospinal injury, and burns - all of which lead to a significantly increased risk of mortality and presents as a separate, more severe entity than non-traumatic or environmental hypothermia. TIH is a ubiquitous concern regardless of the environment as it can occur even in warm climates, as has been the experience in the Middle East.5

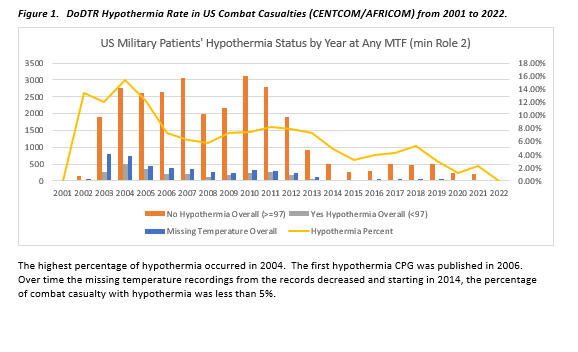

The Hypothermia CPG, initially published in 2006, was one of the first JTS CPGs. Prior to this, the rate of hypothermia (Temp <97 F) in patients arriving to the first role of care was as high as 15.42% in 2004. The rate initially dropped by over half to 7.26%. While it slowly increased again, it should be noted that missing temperature data in the DoD Trauma Registry (DoDTR) was as high as 42% when large volumes of casualties were being seen in 2003. The rate of missing data dropped significantly when the CPG was published yet remained in the 10-20% range. It is unclear if the true incidence was higher before 2006, but this potentially shows a Hawthorne effect and the effectiveness of tracking information to inform clinical practice. Figure 1 shows the trend in hypothermia by U.S. Military patients by year at any medical treatment facility (MTF). The purpose of this CPG is to provide guidance for the prevention and management of TIH in the combat casualty throughout the escalating roles of care.

TIH is classified as mild: 34-36 °C, moderate: 32-34 °C, and severe: <32 °C.6

Current literature suggests that about one to two-thirds of trauma patients are hypothermic upon presentation to the emergency department. The mortality of hypothermic patients is approximately twice that of similarly injured normothermic patients.7-10 In another large study of trauma patients requiring massive transfusion, hypothermia (< 36 deg C) on arrival was an independent predictor of mortality and associated with increased blood product consumption.11-13 Furthermore, studies in civilian trauma have shown >80% of non-surviving patients arrived hypothermic with a core temperature < 34 deg C.12 In both civilian and military trauma, 100% mortality has been demonstrated when core temperature reached < 32 deg C.14,15 When hypothermic patients fall below the thermoregulatory threshold for shivering (around 30 deg C), shivering heat production ceases. Therefore, these patients have lost the ability to generate heat and will continue to cool unless actively rewarmed by external sources.16 This can be further exacerbated by pharmacologic treatment with sedatives and paralytics.17,18

Innovation and improved outcomes-based research over the past two decades have improved survivability via addressing coagulopathy and acidosis .1,5,19–22 Early recognition and treatment of hypothermia is an equally important consideration that begins at the point of injury and should be implemented for all combat casualties, particularly patients at risk of experiencing shock. As it is labor and resource intensive to re-warm a casualty, measures to prevent hypothermia should begin as soon as possible with thermal wraps and warmed resuscitation products.5,23,24 There are varying degrees of abilities and resources availability at each echelon role of care, which are discussed in the following sections.

Treatment

- Take early and aggressive steps to prevent further body heat loss and add external heat, when possible, for both trauma and severely burned casualties.

- Minimize casualty’s exposure to cold ground, wind, and air temperatures. Place insulation material between the casualty and any cold surface as soon as possible. Keep protective gear on or with the casualty if feasible.

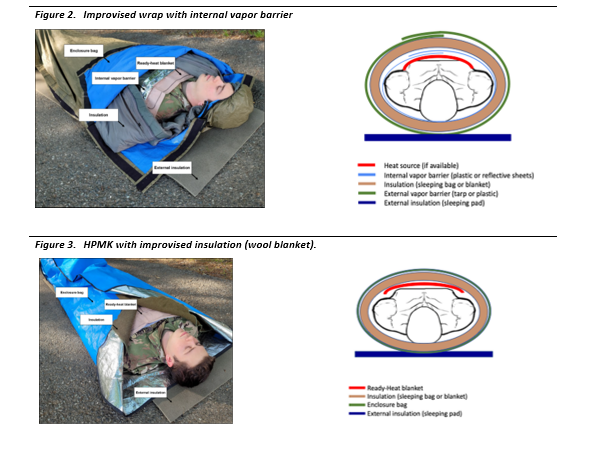

- Replace wet clothing with dry clothing or another thermal barrier (i.e. sleeping bag), if possible, and protect from further heat loss. If unable to replace the dry clothing, wrap an impermeable vapor layer around the casualty. Leave the vapor barrier in place until a warm environment has been reached.

- Place an active heating blanket on the casualty’s anterior torso and under the arms in the axillae (to prevent burns, do not place any active heating source directly on the skin or wrap around the torso). Avoid placing the heat in high pressure areas (i.e. on the back of a supine patient). Regularly monitor the skin under these areas for burns. 25,26,27 See below for information on hypothermia wraps.

- Enclose the casualty with the exterior impermeable enclosure bag. As soon as possible, upgrade hypothermia enclosure system to a well-insulated enclosure system using a hooded sleeping bag or other readily available insulation (i.e. wool blankets) inside the enclosure bag/external vapor barrier shell. The HPMK is non-insulated and therefore suitable only for short term hypothermia prevention, especially in cold climates.

- Pre-stage an insulated hypothermia enclosure system with external active heating for transition from the non-insulated hypothermia enclosure systems; improve upon existing enclosure system when possible.

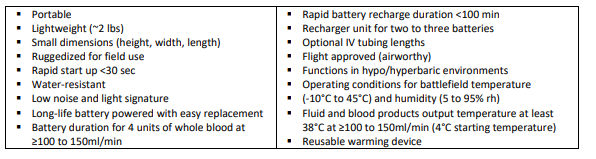

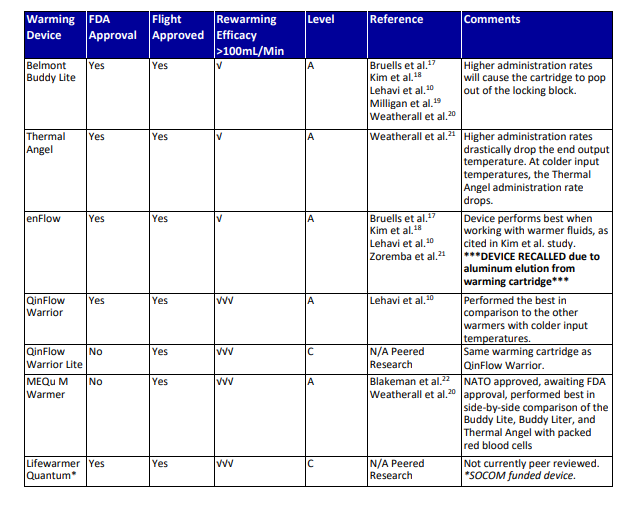

- Use a battery-powered warming device to deliver IV resuscitation fluids, in accordance with current TCCC guidelines, at flow rate up to 150 ml/min with a 38°C output temperature. (See Appendix A.)

- Protect the casualty from exposure to wind and precipitation on any evacuation platform.

- The priority remains the recognition of shock and implementation of heat-loss prevention techniques as outlined above. Rewarming hypothermic patients can be achieved passively (utilizing the patient’s heat generation via shivering/metabolism) and actively (applying an external heat source). If available, active re-warming should be initiated along with passive warming interventions.

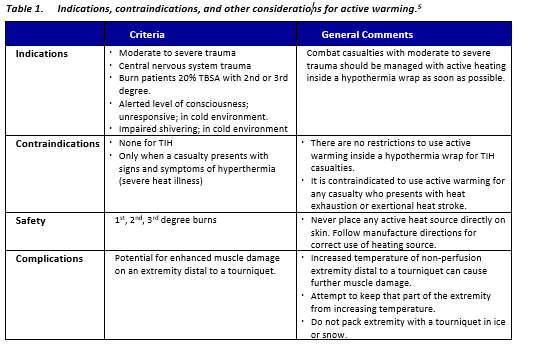

- Active heating: there are no contraindications other than do not use on a heat casualty or those not at risk for hypothermia.28,29 See Figure 2 for the indications, contraindications, and other considerations for active rewarming below.

- Regarding extremity/trauma and tourniquets, research is ongoing regarding the use of extremity tourniquets.30 Priority in TIH is to prevent additional core cooling to mitigate the effects of shock, hypothermia, coagulopathy, and acidosis. Providers may consider leaving the extremity with a tourniquet outside of the insulating wrap, in order to monitor for re-bleeding. This is not recommended as standard practice as the priority should be on the life saving measures of TIH prevention.

- Utilize an insulated hypothermia wrap with an active heating source for all potentially hypothermic trauma patients. Systems that include more insulation and active heating sources perform better for treating/preventing hypothermia but may present limitations when considering portability for field applications.5,24 One of the more widely used systems due to portability, cost, and effectiveness is the HPMK which contains the Ready-Heat Blanket (RHB) - an active warming source and the HRS - essentially an impermeable vapor layer (previous version was the Blizzard blanket).

- Other options include user assembled kits or commercial hypothermia kits, but the recommended characteristics of any hypothermia prevention/treatment system are outlined below. A list of active and passive external rewarming options for field use are shown in (Table 2 - Appendix A).

- Burrito wrap concept with 5 layers as referenced per Bennet et al.

- Active heat source applied to the torso in the following order of precedence: axillae, chest, back. These are the areas with the highest potential for heat transfer.24,25,31 The heat source should not be in direct contact with the patient’s skin.

- Internal vapor layer (plastic or foil sheets)

- Hooded sleeping bag or other insulation (wool blankets)

- Complete with an outer impermeable layer wrapped around all other layers to prevent heat loss, water entry and to block the wind.25

- Use a ground-insulating pad

- Continue and/or initiate above hypothermia interventions.

- Upgrade hypothermia enclosure system to a well-insulated enclosure system using a hooded sleeping bag or other readily available insulation inside the enclosure bag/external vapor barrier shell. Best: Improvised hypothermia wrap with high-quality insulation with cold-rated sleeping bag combined with heat source, internal vapor barrier, outer impermeable enclosure.

- Continue to use a battery-powered warming device to deliver blood at a flow rate up to 150 ml/min hr with a 38°C output temperature. (Table 2).

- Convert to continuous temperature monitoring.

- Minimum: Scheduled temperature measurement with vital sign evaluations.

- Better: Continuous forehead dot monitoring.

- Best: Continuous core temperature monitoring.

- When using the HPMK Ready-Heat Blanket, perform frequent skin checks to monitor for contact burns.

- On patient arrival to the Role 2/3 facility, every effort must be made to prevent hypothermia; this should be a priority throughout resuscitative efforts and operative procedures. Control of ambient air temperature should be utilized to maintain a warm environment.

- Wet clothing and blankets should be removed immediately and a warming device applied if not done prior to arrival or if the device was damaged during transport.

- Use of warmed blood and blankets is indicated, where available, as well as forced air warming devices (Bair Hugger) as applicable.

- Continuous temperature monitoring is preferred, and temperatures should be documented on arrival to and discharge from the facility. A temperature sensing Foley catheter is a viable option to monitor temperature as well as the response to ongoing resuscitation efforts.

- If non-core temperature (oral, axillary, or tympanic) is outside of an expected range (<97F or >100F), use core temperature (rectal or esophageal) measurement for best accuracy.

NOTE: Patient packaging with treatment for TIH is a core skill that should be deliberately planned and rehearsed prior to mission execution. A patient packaged for hypothermia prevention/treatment is difficult to access. Medical providers need to be cognizant of this fact and have a plan to monitor their patient’s status as well as their prior medical interventions.

- Ensure hypothermia management from the field is still in place and has not moved and or shifted during turnover. Ensure the hypothermia management system is covering the back and the system is protecting the patient from wind blowing over or under the casualty, especially in a rotary wing environment.

- Use of vehicle or aircraft Environmental Control Systems (ECS) should be used to create an ambient control temperature to allow passive room warming. ECS Systems can be unreliable, especially in rotary wing when power is limited. In preplanning, the ECS can be used to set a warm environment prior to or after receiving the casualty, to prevent drastic temperature loss.

- The use of continuous temperature monitoring should be conducted to establish and track warming trending.

- When moving patients in the maritime environment, doubling up of outer layering impermeable systems should be utilized to protect the patient from winds and sea spray.

FIELD “TRICKS OF THE TRADE” + ANECDOTAL “TROUBLE SHOOTING”

- Use RHB/active rewarming systems in maritime environment.

- On scene materials/clean trash bags or saran wrap may be helpful improvised insulation materials.

- Vehicle heating systems may help direct hot air to a patient in a field expedient Bair Hugger in certain platforms. This requires prior coordination and setup and is a non-standard equipment load.

- Use of thermal heat packs (crush packs, Ready Heat 1 Panel Blanket, MRE heater, even Foley bag in extremis) or body heat for fluid pre-warming (of most utility in Ruck-Truck-House phases when fluid warmers might be in short supply) Note: Do not place directly on skin to prevent thermal injury to patient.

- Expect issues with finger pulse-ox devices. If value shown does not correlate to patient presentation, remember to treat the patient, not the device. Taping heat pack over hand, but not in direct contact with the skin and device, may aid in accuracy/operation.

- In extreme cold weather (below -20°F), exhalation gas from intubated patients may cause ice to instantly form in the ET tube and vent tubing. Care should be taken to insulate all interventions while exposed to these conditions.

Performance Improvement (PI) Monitoring

All trauma patients meeting DoDTR inclusion criteria with ISS>1.

- Temperature and route will be documented on all patients upon admission and discharge.

- Core temperatures are obtained on all patients with temperature <96 F and > 100° F.

- Warming measures and sustainment of core temperature > 96°.F are initiated on all patients.

PERFORMANCE/ADHERENCE MEASURES

- Temperature and route will be documented on all patients upon admission and discharge.

- Core temperatures are obtained on all patients with temperature <96 F and > 100° F.

- Warming measures and sustainment of core temperature > 96°.F are initiated on all patients.

- Patient Record

- DoDTR

- The above constitutes the minimum criteria for PI monitoring of this CPG. System reporting will be performed annually; additional PI monitoring and system reporting may be performed as needed.

- The system review and data analysis will be performed by the JTS Chief and the JTS PI Branch.

- For more information on metrics, email: jbsa.healthcare-ops.list.jts-pips@health.mil

It is the trauma team leader’s responsibility to ensure familiarity, appropriate compliance, and PI monitoring at the local level with this CPG.

References

- Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): Implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 SUPPL. 5):431-437.

- Gerhardt RT, Strandenes G, Cap AP, et al. Remote damage control resuscitation and the Solstrand Conference: Defining the need, the language, and a way forward. Transfusion. 2013;53(SUPPL. 1):9S-16S.

- Mikhail J. The trauma triad of death: hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy. AACN Clin Issues. 1999;10(1):85-94.

- Moffatt SE. Hypothermia in trauma. Emerg Med J. 2013;30(12):989-996. doi:10.1136/emermed-2012-201883

- Bennett BL, Giesbrect G, Zafren K, et al. Management of hypothermia in tactical combat casualty care: TCCC guideline proposed change 20-01 (June 2020). J Spec Oper Med. 2020;20(3):21-35.

- Gentilello LM. Advances in the management of hypothermia. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:243-256.

- Balvers K, Van Der Horst M, Graumans M, et al. Hypothermia as a predictor for mortality in trauma patients at admittance to the intensive care unit. J Emergencies, Trauma Shock. 2016;9(3):97-102.

- Joint Trauma System Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypothermia prevention, monitoring, and management. 2012;(September):1-11.

- Simmons JW, Powell MF. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: Pathophysiology and resuscitation. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117:iii31-iii43.

- Wang HE, Callaway CW, Peitzman AB, Tisherman SA. Admission hypothermia and outcome after major trauma. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(6):1296-1301.

- Lester ELW, Fox EE, Holcomb JB, et al. The impact of hypothermia on outcomes in massively transfused patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(3):458-463.

- Fisher AD, April MD, Schauer SG. An analysis of the incidence of hypothermia in casualties presenting to emergency departments in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;38(11):2343-2346.

- Beilman GJ, Blondet JJ, Nelson TR, et al. Early hypothermia in severely injured trauma patients is a significant risk factor for multiple organ dysfunction syndrome but not mortality. Ann Surg. 2009;249(5):845-850.

- Gentilello LM, Jurkovich GJ, Stark MS, Hassantash SA, O’Keefe GE. Is hypothermia in the victim of major trauma protective or harmful? A randomized, prospective study. Ann Surg. 1997;226(4):439-449.

- Holcomb JB. The 2004 Fitts Lecture: Current perspective on combat casualty care. In: Journal of Trauma - Injury, Infection and Critical Care. Vol 59. ; 2005:990-1002.

- Brown DJA, Brugger H, Boyd J, Paal P. Accidental Hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1930-1938. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1114208

- Lopez MB. Postanaesthetic shivering - from pathophysiology to prevention. Rom J Anaesth Intensive Care. 2018;25(1):73-81.

- Kurdi M, Theerth K, Deva R. Ketamine: Current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8(3):283.

- Shackelford SA, Del Junco DJ, Powell-Dunford N, et al. Association of prehospital blood product transfusion during medical evacuation of combat casualties in Afghanistan with acute and 30-day survival. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2017;318(16):1581-1591.

- Blackbourne LH, Baer DG, Eastridge BJ, et al. Military medical revolution: Prehospital combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6 SUPPL. 5):372-377.

- Kragh JF, Dubick MA, Aden JK, et al. U.S. military use of tourniquets from 2001 to 2010. Prehospital Emerg Care. 2015;19(2):184-190.

- Dickey NW. Combat Trauma Lessons Learned from Military Operations of 2001-2013. Def Heal Agency/Defense Heal Board Falls Church United States. 2015:82.

- Nicholson B, Neskey J, Stanfield R, et al. Integrating Prolonged Field Care into Rough Terrain and Mountain Warfare Training: The Mountain Critical Care Course. J Spec Oper Med. 2019;19(1):66-69.

- Haverkamp FJC, Giesbrecht GG, Tan ECTH. The prehospital management of hypothermia — An up-to-date overview. Injury. 2018;49(2):149-164.

- Dow J, Giesbrecht GG, Danzl DF, et al. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Out-of-Hospital Evaluation and Treatment of Accidental Hypothermia: 2019 Update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(4):S47-S69.

- Allen PB, Salyer SW, Dubick MA, Holcomb JB, Blackbourne LH. Preventing hypothermia: Comparison of current devices used by the Us Army in an in vitro warmed fluid model. J Trauma - Inj Infect Crit Care. 2010;69(SUPPL. 1):S154-S161.

- Giesbrecht GG, Walpoth BH. Risk of Burns During Active External Rewarming for Accidental Hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(4):431-436.

- Knapik JJ, Epstein Y. Exertional Heat Stroke: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. J Spec Oper Med. 2019;19(2):108-116.

- Lipman GS, Gaudio FG, Eifling KP, Ellis MA, Otten EM, Grissom CK. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Heat Illness: 2019 Update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(4):S33-S46.

- Shackelford SA, Butler FK Jr, Kragh JF Jr, et al. Optimizing the use of limb tourniquets in tactical combat casualty care: TCCC Guidelines Change 14-02. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15(1):17-31.

- Ducharme MB, Tikuisis P. Role of blood as heat source or sink in human limbs during local cooling and heating. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76(5):2084-2094.

APPENDIX A: EQUIPMENT LIST

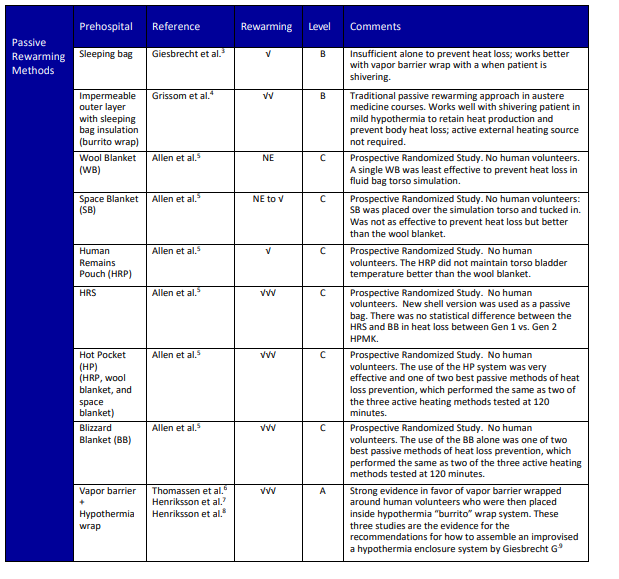

Table 1. Passive Rewarming Methods

- Level A: Evidence from multiple randomized trials or meta-analyses.

- Level B: Evidence from a single randomized trial or non-randomized studies.

- Level C: Expert opinion, case studies, or standards of care.

- NE = not effective; √ = mildly effective; √√ = moderately effective; √√√ = highly effective

CAUTION: Devices A-B should NOT be placed under the patient’s back or directly on bare skin. Doing so may increase the likelihood of thermal burns or render the device inoperable.

HAWK Warming Grid

- https://soldiersystems.net/2020/01/28/nsns-for-hawk-warming-grid/

- Air activated and heat adjustable. Can reseal individual cells for optimal performance.

- Conditions below 0F may require extended time (+15 minutes) to reach operating temperature

- 4-32 hours of operation

Ready-Heat Panel Blanket

- https://www.ready-heat.com/products/military/

- Air activated, NOT heat adjustable

- Conditions below 0F require extended time (+ 30 minutes) to reach operating temperature.

- Rendered inoperable by fluids and must ensure patient is dry prior to application and keep away from potential fluid sources.

- 8-10 hours of operation

Geratherm Mini Rescue II Hypothermia Kit

- rgmd.com

- Currently in the SOCOM Tribalco T-5 CASEVAC Kit

Chill Buster Blanket

Wiggy’s or down sleeping bag

Desirable Characteristics of a Resuscitation Fluid Warming Device

List of warming devices available on the market.

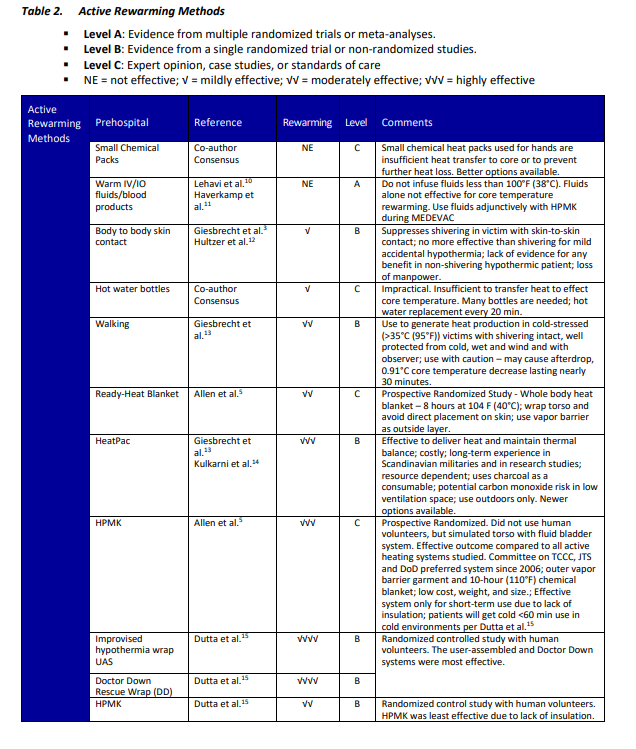

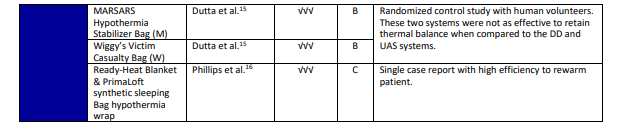

- Level A: Evidence from multiple randomized trials or meta-analyses.

- Level B: Evidence from a single randomized trial or non-randomized studies.

- Level C: Expert opinion, case studies, or standards of care.

Abbreviations: √, mildly effective; √√, moderately effective; √√√, highly effective

Section 3: Temperature Monitoring

Temperature Monitoring Devices

- Temperature sensing Foley

- (Forehead) temperature sensing ‘dots’

- DataTherm(R)II Continuous Temperature Monitor - in the SOCOM Tribalco T-5 Cardiac Ki

- Propaq MD

- Airworthiness approved

- BATDOK (Battlefield Assisted Trauma Distributed Observation Kit) enabled

- Several different options available for real-time temperature monitoring

- Philips Tempus Pro - Airworthiness approved

- Welch Allyn SureTemp - Airworthiness approved

- 3M Bair Hugger Temperature Monitoring System23 - Portable device still under development, but may have applicability in the trauma setting

References

- Bennett BL, Giesbrect G, Zafren K, et al. Management of hypothermia in tactical combat casualty care: TCCC Guideline Proposed Change 20-01 (June 2020). J Spec Oper Med. 2020;20(3):21-35.

- Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, et al. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines. 2009;25;301(8):831-841.

- Giesbrecht GG, Sessler DI, Mekjavic IB, et al. Treatment of mild immersion hypothermia by direct body-to-body contact. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:2373-2379.

- Grissom CK, Harmston CH, McAlpine JC, et al. Spontaneous endogenous core temperature rewarming after cooling due to snow burial. Wilderness Environ Med. 2010;21(3):229-235.

- Allen PB, Salyer SW, Dubick MA, Holcomb JB, Blackbourne LH. Preventing hypothermia: Comparison of current devices used by the Us Army in an in vitro warmed fluid model. J Trauma - Inj Infect Crit Care. 2010;69(SUPPL. 1):S154-S161.

- Thomassen O, Faerevik H, Osteras O, et al. Comparison of three different prehospital wrapping methods for preventing hypothermia – a cross over study in humans. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19:41.

- Henriksson O, Lundgren PJ, Kuklane K, et al. Protection against cold in prehospital care: Wet clothing removal or addition of a vapor barrier. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26(1):11-20.

- Henriksson O, Lundgren P, Kuklane K, et al. Protection against cold in prehospital care: evaporative heat loss reduction by wet clothing removal or the addition of a vapor barrier – a thermal manikin study. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2012;27:53-58.

- Giesbrecht G. Cold card to guide responders in the assessment and care of cold-exposed patients. Wilderness Environ Med. 2018;29(4):499-503.

- Lehavi A, Yitzhak A, Jarassy R, Heizler R, Katz Y (Shai), Raz A. Comparison of the performance of battery-operated fluid warmers. Emerg Med J. 2018;35(9):564-570.

- Haverkamp FJC, Giesbrecht GG, Tan ECTH. The prehospital management of hypothermia — An up-to-date overview. Injury. 2018;49(2):149-164.

- Hultzer MV, Xu X, Marrao C, et al. Pre-hospital torso-warming modalities for severe hypothermia: a comparative study using a human model. 2005;7:378-386.

- Giesbrecht GG, Bristow GK, Uin A, et al. Effectiveness of three field treatments for induced mild (33.0C) hypothermia. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63(6):2375-2379.

- Kulkarni K, Hildahl E, Dutta R, et al. Efficacy of head and torso rewarming using a human model for severe hypothermia. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(1):35-43.

- Dutta R, Kulkarni K, Steinman A, et al. Human responses to five heated hypothermia enclosure systems in a cold environment. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019:30(2):163-176.

- Phillips D, Bowman J, Zafren K. Successful rewarming of a patient with apparent moderate hypothermia using a hypothermia wrap and a chemical heat blanket. Wilderness Environ med. 2019;30(2):199-202.

- Bruells CS, Bruells AC, Rossaint R, Stoppe C, Schaelte G, Zoremba N. A laboratory comparison of the performance of the buddy lite™ and enFlow™ fluid warmers. Anaesthesia. 2013;68(11):1161-1164.

- Kim HJ, Yoo SM, Jung JS, Lee SH, Sun K, Son HS. The laboratory performance of the enFLOW(®) , buddy lite(™) and ThermoSens(®) fluid warmers. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(2):205-208.

- Milligan J, Lee A, Gill M, Weatherall A, Tetlow C, Garner AA. Performance comparison of improvised prehospital blood warming techniques and a commercial blood warmer. Injury. 2016;47(8):1824-1827.

- Weatherall A, Gill M, Milligan J, et al. Comparison of portable blood-warming devices under simulated pre-hospital conditions: a randomised in-vitro blood circuit study. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(8):1026-1032.

- Zoremba N, Bruells C, Rossaint R, Breuer T. Heating capabilities of small fluid warming systems. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):98.

- Blakeman T, Fowler J, Branson R, Petro M, Rodriguez D. Performance characteristics of fluid warming technology in austere environments. J Spec Oper Med. 2021 Spring; 21(1):18-24.

- Conway A, Bittner M, Phan D, Chang K, Kamboj N, Tipton E, Parotto M. Accuracy and precision of zero-heat-flux temperature measurements with the 3M™ Bair Hugger™ Temperature monitoring system: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Monit Comput. 2020 Jun 2.

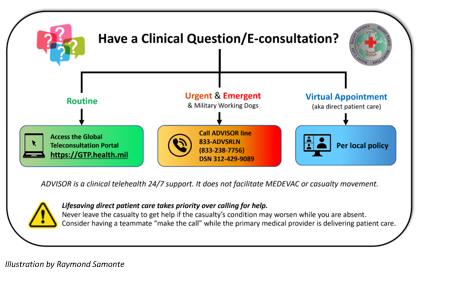

APPENDIX B: TELEMEDICINE /TELECONSULTATION

APPENDIX C: INFORMATION REGARDING OFF-LABEL USES IN CPGS

Purpose

The purpose of this Appendix is to ensure an understanding of DoD policy and practice regarding inclusion in CPGs of “off-label” uses of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products. This applies to off-label uses with patients who are armed forces members.

Background

Unapproved (i.e. “off-label”) uses of FDA-approved products are extremely common in American medicine and are usually not subject to any special regulations. However, under Federal law, in some circumstances, unapproved uses of approved drugs are subject to FDA regulations governing “investigational new drugs.” These circumstances include such uses as part of clinical trials, and in the military context, command required, unapproved uses. Some command-requested, unapproved uses may also be subject to special regulations.

Additional Information Regarding Off-Label Uses in CPGs

The inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is not a clinical trial, nor is it a command request or requirement. Further, it does not imply that the Military Health System requires that use by DoD health care practitioners or considers it to be the “standard of care.” Rather, the inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is to inform the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner by providing information regarding potential risks and benefits of treatment alternatives. The decision is for the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner within the practitioner-patient relationship.

Additional Procedures

Balanced Discussion

Consistent with this purpose, CPG discussions of off-label uses specifically state that they are uses not approved by the FDA. Further, such discussions are balanced in the presentation of appropriate clinical study data, including any such data that suggest caution in the use of the product and specifically including any FDA-issued warnings.

Quality Assurance Monitoring

With respect to such off-label uses, DoD procedure is to maintain a regular system of quality assurance monitoring of outcomes and known potential adverse events. For this reason, the importance of accurate clinical records is underscored.

Information to Patients

Good clinical practice includes the provision of appropriate information to patients. Each CPG discussing an unusual off-label use will address the issue of information to patients. When practicable, consideration will be given to including in an appendix an appropriate information sheet for distribution to patients, whether before or after use of the product. Information to patients should address in plain language: a) that the use is not approved by the FDA; b) the reasons why a DoD health care practitioner would decide to use the product for this purpose; and c) the potential risks associated with such use.