TFC Hemorrhage Control

JTS / CoTCCC

Introduction

Tactical Field Care (TFC) is the care rendered by the first responder or combatant once no longer under effective hostile fire. It also applies to situations in which an injury has occurred, but there has been no hostile fire. Available medical equipment is still limited to that carried into the field by unit personnel. Time to evacuation to a medical treatment facility may vary considerably. Tactical field care allows more time and a little more safety to provide further medical care. But Remember – effective hostile fire could resume at any time.

The first treatment step in the Tactical Field Care Phase of Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) is to assess for unrecognized hemorrhage and control all sources of bleeding. Hemorrhage control can be achieved during the TFC phase by applying a pelvic binder, applying a tourniquet to severe limb bleeding if not already done, assessing tourniquet placement and effectiveness, replacing a “high-and-tight” tourniquet or adding a second tourniquet, converting the tourniquet to a hemostatic or pressure dressing when possible, and using a junctional tourniquet if indicated. Additionally, this module will discuss the various types of TCCC approved tourniquets, tourniquet conversion criteria/techniques, and use of hemostatic dressings.

Objectives

- DESCRIBE the progressive strategy for controlling hemorrhage in tactical field care.

- DEMONSTRATE the correct application of a CoTCCC-recommended hemostatic dressing.

- DEMONSTRATE the correct application of a CoTCCC-recommended junctional tourniquet.

- DEMONSTRATE the correct application of a pelvic binder.

Videos

Key Points

Establish a security perimeter in accordance with unit tactical standard operating procedures and/or battle drills. Maintain tactical situational awareness.

Triage casualties as required. Casualties with an altered mental status should immediately have weapons cleared and secured, communications secured, and sensitive mission items redistributed.

During the Tactical Field Care of TCCC, further efforts can be made to achieve hemorrhage control.

- Assess for unrecognized hemorrhage and control all sources of bleeding. If not already done, use a CoTCCC-recommended limb tourniquet to control life-threatening external hemorrhage that is anatomically amenable to tourniquet use or for any traumatic amputation. Apply directly to the skin 2-3 inches above the bleeding site. If bleeding is not controlled with the first tourniquet, apply a second tourniquet side-by-side with the first.

- For compressible hemorrhage not amenable to limb tourniquet use or as an adjunct to tourniquet removal, use one of the CoTCCC-recommended hemostatic dressings.

Hemostatic dressings should be applied with at least 3 minutes of direct pressure. Each dressing works differently, so if one fails to control bleeding, it may be removed and a fresh dressing of the same type or a different type applied.

If the bleeding site is amenable to use of a junctional tourniquet, immediately apply a CoTCCC-recommended junctional tourniquet. Do not delay in the application of the junctional tourniquet once it is ready for use. Apply hemostatic dressings with direct pressure if a junctional tourniquet is not available or while the junctional tourniquet is being readied for use.

Junctional Areas include the groin, buttocks, perineum, axilla, base of the neck, and extremities at sites too proximal for a limb tourniquet.

A pelvic binder should be applied for cases of suspected pelvic fracture:

- Severe blunt force or blast injury with one or more of the following indications:

- Pelvic pain

- Any major lower limb amputation or near amputation

- Physical exam findings suggestive of a pelvic fracture

- Unconsciousness

- Shock

Reassess prior tourniquet application. Expose the wound and determine if a tourniquet is needed. If it is needed, replace any limb tourniquet placed over the uniform with one applied directly to the skin 2-3 inches above bleeding site. Ensure that bleeding is stopped. If there is no traumatic amputation, a distal pulse should be checked. If bleeding persists or a distal pulse is still present, consider additional tightening of the tourniquet or the use of a second tourniquet side-by-side with the first to eliminate both bleeding and the distal pulse. If the reassessment determines that the prior tourniquet was not needed, then remove the tourniquet and note time of removal on the TCCC Casualty Card.

Although a tourniquet may stop the active bleeding, it also prevents venous blood from returning to the heart. If arterial blood continues to flow past the tourniquet, pressure can build up distally in the limb and create a compartment syndrome. This is why the tourniquet should be tightened until there is no longer a distal pulse – to minimize the chance of harm from a developing compartment syndrome.

Limb tourniquets and junctional tourniquets should be converted to hemostatic or pressure dressings as soon as possible if three criteria are met: the casualty is not in shock, it is possible to monitor the wound closely for bleeding, and the tourniquet is not controlling bleeding from an amputated extremity. Every effort should be made to convert tourniquets in less than 2 hours if bleeding can be controlled with other means. Do not remove a tourniquet that has been in place more than 6 hours unless close monitoring and lab capability are available.

- The casualty is in shock.

- You cannot closely monitor the wound for re-bleeding.

- The extremity distal to the tourniquet has been traumatically amputated.

- The tourniquet has been on for more than 6 hours.

- The casualty will arrive at a medical treatment facility within 2 hours after time of application….or

- Tactical or medical considerations make transition to other hemorrhage control methods inadvisable.

Expose and clearly mark all tourniquets with the time of tourniquet application. Note tourniquets applied and time of application; time of reapplication; time of conversions; and time of removal on the TCCC Casualty Card. Use a permanent marker to mark on the tourniquet and the casualty card.

Summary

Immediate v Delayed Fluid RES for Hypotensive Patients with Penetrating Torso Injuries

Immediate Versus Delayed Fluid Resuscitation for Hypotensive Patients with Penetrating Torso Injuries

William H. Bickell, MD., Matthew J. Wall, Jr., M.D., Paul E. Pepe, MD., R. Russell Martin, MD., Victoria F. Ginger, MSN., Mary K. Allen, BA., and Kenneth L. Mattox, MD.

The New England Journal of Medicine 2012;331(17):1105-1109.

Fluid resuscitation may be detrimental when given before bleeding is controlled in patients with trauma. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of delaying fluid resuscitation until the time of operative intervention in hypotensive patients with penetrating injuries to the torso.

This was a prospective trial comparing immediate and delayed fluid resuscitation in 598 adults with penetrating torso injuries who presented with a prehospital systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg. Patients assigned to the immediate-resuscitation group received standard fluid resuscitation before they reached the hospital and in the trauma center, and those assigned to the delayed-resuscitation group received intravenous cannulation but no fluid resuscitation until they reached the operating room.

Among the 289 patients who received delayed fluid resuscitation, 203 (70%) survived and were discharged from the hospital, as compared with 193 of the 309 patients (62%) who received immediate fluid resuscitation. The mean estimated intraoperative blood loss was similar in the two groups. Among the 238 patients in the delayed-resuscitation group who survived to the postoperative period, 55 (23%) had one or more complications (adult respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis syndrome, acute renal failure, coagulopathy, wound infection, and pneumonia), as compared with 69 of the 227 patients (30%) in the immediate-resuscitation group. The duration of hospitalization was shorter in the delayed-resuscitation group.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

Mil Application of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma RES (MATTERs) Study

Military Application of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma Emergency Resuscitation (MATTERs) Study

Jonathan J. Morrison, MB ChB, MRCS; Joseph J. Dubose, MD; Todd E. Rasmussen, MD; Mark J. Midwinter, BMedSci, MD, FRCS

Archives of Surgery 2012;147(2):113-119.

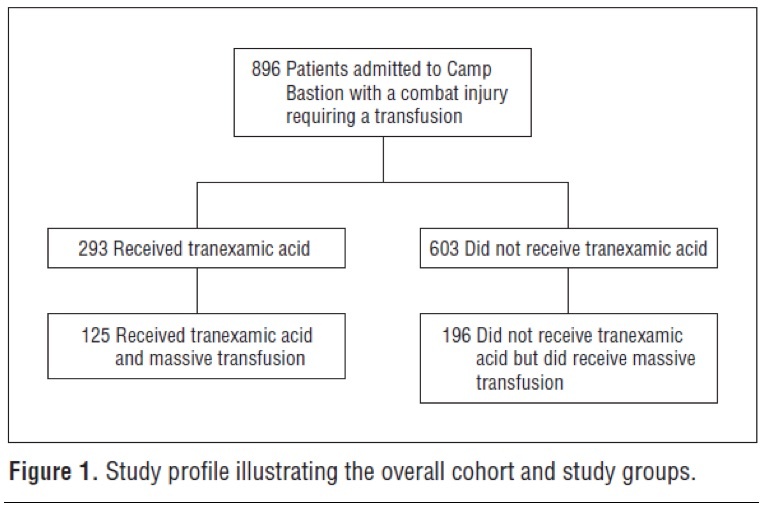

The purpose of this study was to characterize contemporary use of tranexamic acid (TXA) in combat injury and to assess the effect of its administration on total blood product use, thromboembolic complications, and mortality. This was a retrospective observational study comparing TXA administration with no TXA in patients receiving at least 1 unit of packed red blood cells. A subgroup of patients receiving massive transfusion (greater than 10 units of packed red blood cells) was also examined.

A total of 896 consecutive combat injury admissions to a Role 3 Echelon surgical hospital in southern Afghanistan were evaluated (of the 896 injured patients, 293 received TXA). Outcome measures included mortality at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 30 days as well as the influence of TXA administration on postoperative coagulopathy and the rate of thromboembolic complications.

The TXA group had lower unadjusted mortality than the no-TXA group (17.4% vs 23.9%, respectively) despite being more severely injured. This benefit was greatest in the group of patients who received massive transfusion , where TXA was also independently associated with survival and less coagulopathy.

Take Home Message:

Mechanism of Action of Tranexamic Acid in Bleeding Trauma Patients

Mechanism of action of tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of data from the CRASH-2 trial

Ian Roberts, David Prieto-Merino and Daniela Manno

Critical Care 2014, 18:685

To investigate the mechanism of action of tranexamic acid (TXA) in bleeding trauma patients, the authors examined the timing of its effect on mortality. The working hypothesis was the following-- if TXA reduces mortality by decreasing blood loss, its effect should be greatest on the day of the injury when bleeding is most profuse. However, if TXA reduces mortality via an anti-inflammatory mechanism its effect should be greater over the subsequent days. This paper is an exploratory analysis, including per-protocol analyses, of data from the CRASH-2 trial, a randomized placebo controlled trial of the effect of TXA on mortality in 20,211 trauma patients with, or at risk of, significant bleeding.

The effect of TXA on mortality is greatest for deaths occurring on the day of the injury. This survival benefit is only evident in patients in whom treatment is initiated within 3 hours of their injury. Initiation of TXA treatment within 3 hours of injury reduced the hazard of death due to bleeding on the day of the injury by 28%. TXA treatment initiated beyond 3 hours of injury appeared to increase the hazard of death due to bleeding, although the estimates were imprecise. Early administration of tranexamic acid appears to reduce mortality primarily by preventing exsanguination on the day of the injury.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

Eliminating Preventable Death on the Battlefield

Eliminating Preventable Death on the Battlefield

Russ S. Kotwal, MD, MPH; Harold R. Montgomery, NREMT; Bari M. Kotwal, MS; Howard R. Champion, FRCS; Frank K. Butler Jr, MD; Robert L. Mabry, MD; Jeffrey S. Cain, MD; Lorne H. Blackbourne, MD; Kathy K. Mechler, MS, RN; John B. Holcomb, MD

Archives of Surgery 2011;146(12):1350-1358

The objective of this paper was to evaluate battlefield survival in a novel command-directed casualty response system that comprehensively integrates Tactical Combat Casualty Care guidelines and a prehospital trauma registry. Information was obtained via an analysis of battle injury data collected from the 75th Ranger Regiment, US Army Special Operations Command during combat deployments in Afghanistan and Iraq from October 1, 2001 through March 31, 2010. Casualties were scrutinized for preventable adverse outcomes and opportunities to improve care. Comparisons were made with Department of Defense casualty data for the military as a whole.

A total of 419 battle injury casualties were incurred during 7 years of continuous combat in Iraq and 8.5 years in Afghanistan. Despite higher casualty severity indicated by return-to-duty rates, the regiment’s rates of 10.7% killed in action and 1.7% who died of wounds were lower than the Department of Defense rates of 16.4% and 5.8%, respectively, for the larger US military population. Of 32 fatalities incurred by the regiment, none died of wounds from infection, none were potentially survivable through additional prehospital medical intervention, and 1 was potentially survivable in the hospital setting. Substantial prehospital care was provided by nonmedical personnel.

Take Home Message:

US Rangers in Somalia: An Analysis of Combat Casualties on an Urban Battlefield

United States Army Rangers in Somalia: An Analysis of Combat Casualties on an Urban Battlefield

Robert L. Mabry, MD, John B. Holcomb, MD, Andrew M. Baker, MD, Clifford C. Cloonan, MD, John M. Uhorchak, MD, Denver E. Perkins, MD, Anthony J. Canfield, MD, and John H. Hagmann, MD

The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 2000, Volume 49(3)

This study was undertaken to determine the differences in injury patterns between soldiers equipped with modern body armor in an urban environment compared with the soldiers of the Vietnam War. From July 1998 to March 1999, data were collected for a retrospective analysis on all combat casualties sustained by United States military forces in Mogadishu, Somalia, on October 3 and 4, 1993. This was the largest and most recent urban battle involving United States ground forces since the Vietnam War.

There were 125 combat casualties. Casualty distribution was similar to that of Vietnam; 11% died on the battlefield, 3% died after reaching a medical facility, 47% were evacuated, and 39% returned to duty. No missiles penetrated the solid armor plate protecting the combatants’ anterior chests and upper abdomens. Most fatal penetrating injuries were caused by missiles entering through areas not protected by body armor, such as the face, neck, pelvis, and groin. Three patients with penetrating abdominal wounds died from exsanguination, and two of these three died after damage-control procedures.

At the time of this study, United States Army doctrine on prehospital care did not include antibiotic administration by medics in the field. Information on field use of antibiotics in this battle is only anecdotal, but it seems that very few of the casualties received antibiotics before reaching a casualty collection point or hospital. Early administration of antibiotics to combat casualties is recommended in many studies. The NATO Emergency War Surgery Handbook suggests that parenteral antibiotics be given as early as possible to all patients with penetrating abdominal injuries, open comminuted fractures, and extensive soft-tissue extremity wounds. Because evacuation to definitive surgical care is likely to be delayed more than 6 hours in future urban conflicts, antibiotic therapy should be initiated by medics in the field, preferably within the first hour of injury.