Nutritional Support Using Enteral and Parenteral Methods

Joint Trauma System

Nutritional Support Using Enteral and Parenteral Methods

PURPOSE

- To define an approach to optimal nutritional support in the critically ill or injured patient.

- To establish meaningful goals for implementing enteral nutrition.

- To provide an understanding of the various formulations for enteral nutrition and their use.

- To establish the indications for total parenteral nutrition.

Definitions

- Enteral Nutrition (EN): The use of the stomach, duodenum, or jejunum to provide the nutrition targets to optimize healing and normal physiologic function.

- Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN): Formulated nutritional substrate provided intravenously to optimize healing and normal physiologic function.

Guidelines

- Consult medical nutrition therapy on all ICU patients for nutritional assessment and cooperative guidance on nutritional support.

- Consider tele-consultation to next level of care if Medical Nutrition Therapy services are not available locally.

- Enteral nutrition should be the first choice over total parenteral nutrition for the patients unable to consume food on their own. Enteral nutrition maintains gut mucosal integrity and immunocompetence.

- When compared to parenteral nutrition, EN in appropriately selected patients has been associated with a decrease in infectious complications, decreased hospital length of stay and a significant reduction in ICU length of stay

- It is important to note that the maximal benefit of enteral nutrition is obtained when it is started early (within 48 hours of admission) and that the benefit does not appear to be dose-dependent, so even low-rate (trickle) feeding can improve outcomes.1,2

Enteral Nutrition

Indications for Enteral Nutrition

- Any patient on the trauma service who is anticipated to remain unable to take full oral intake on their own for greater than 5-7 days.

- Any patient who has oral intake with supplementation that is inadequate to meet current nutritional needs (i.e., < 50% of estimated required calories for >3 days.)

- Any patient with pre-existing malnutrition (>15% involuntary weight loss or pre-injury albumin < 3 g/dl) or categorized as “high nutritional risk” based on a validated nutritional risk scoring system and unable to immediately resume full oral intake. It should be emphasized that for albumin to be useful as a nutrition maker, it should be obtained prior to injury. However, in the combat trauma setting, a pre-injury albumin level is unlikely to be available. Further, albumin measured during acute illness should not be used or followed as a marker of nutrition as it is an acute phase reactant and will markedly decrease during the initial period of critical illness. An initial pre-albumin level is also less useful immediately after injury, but serial pre-albumin levels can be useful during the resolution and recovery phase. If utilized pre-albumin should not be checked more frequently than once weekly.1-4

Absolute Contraindications for Enteral Nutrition

- High risk for non-occlusive bowel necrosis

- Active shock or ongoing resuscitation

- Persistent mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 60mmHg

- Increasing requirement for vasoactive support to maintain MAP>60mmHg

- Generalized peritonitis

- Intestinal obstruction

- Surgical discontinuity of bowel

- Paralytic ileus

- Intractable vomiting/diarrhea refractory to medical management

- Known or suspected mesenteric ischemia

- Major gastrointestinal bleed

- High output uncontrolled fistula 1-3

Relative Contraindications for Enteral Nutrition

- Body temperature < 96 F

- Concern for abdominal compartment syndrome as evidenced by bladder pressure > 25mmHg 1-3

Parenteral Nutrition

Indications for Parenteral Nutrition

-

Unable to meet > 50% caloric needs through an enteral route by post-injury day #7

-

Any of the contraindications for enteral nutrition listed in above that persist and patient is without nutritional support for 3 days or patient is not anticipated to start enteral nutrition for more than 3-5 days.

-

Massive small bowel resection refractory to enteral feeds.

-

High output fistula after failure of elemental diet.

-

Any patient with pre-existing malnutrition (>15% involuntary weight loss or pre-injury albumin < 3 g/dl) or categorized as “high nutritional risk” based on a validated nutritional risk scoring system (NUTRIC or other) and with contraindication or intolerance to enteral feeding. 1-4

Enteral Access

-

Enteral access will be established ideally within 24 hours of admission to the Role 3 or higher Medical Treatment Facility (MTF).1-3,5,6

-

If the patient will be taken to the operating room within 24-48 hours of arrival for laparotomy procedure, a naso-jejunal feeding tube (NJFT) should be placed while the patient is in the operating room (OR). While in the civilian setting in intubated patients there is no difference in outcomes when comparing EN via the naso-jejunal versus gastric route, however enteral access distal to the stomach is recommended, particularly in those patients at risk for aspiration. Due to the intermittent nature of gastric feedings and the need for frequent holdings for patient aeromedical evacuation and/or procedures in the combat environment, it is emphasized that this is NOT the preferred initial method of feeding these patients. However if this is not practical, in many patients it is acceptable to initiate gastric EN. 1,3

-

If the patient is not a candidate for operative placement, use whatever means available to place a feeding tube. (e.g., endoscopic, fluoroscopic, etc.).

-

If unable to place a NJFT, consider the use of an Oro-Gastric (OG) or Naso-Gastric (NG) tube, with intent to discontinue enteral feeds 6 hours prior to transfer.

-

If prolonged enteral feeding (>4 weeks) is expected, then placement of a surgical feeding tube should be considered. A gastrostomy, jejunostomy, or combined gastro-jejunostomy should be considered prior to final closure of any open abdomen patient, and the risks versus benefits of each option along with the existing patient gastrointestinal anatomy will dictate the choice of surgical feeding access. 1-6

Nutritional Energy/Protein Requirements

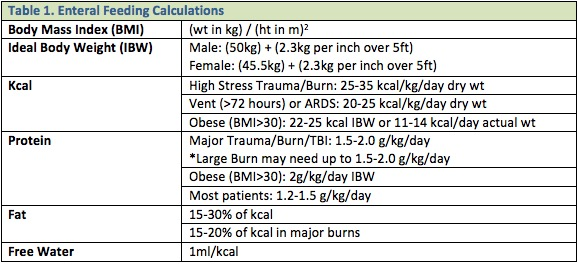

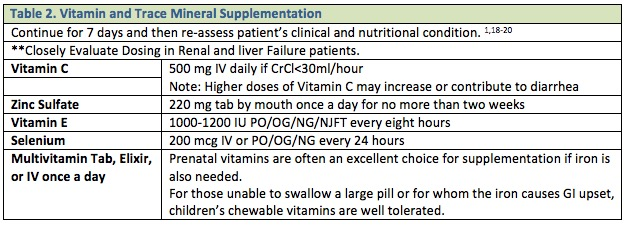

Nutritional energy/protein requirements are based on the patient’s current nutritional status and severity/type of trauma suffered. The previous practices of over-feeding critically ill or injured patients by multiplying a calculated caloric goal by some “stress factor”, or increasing caloric intake above the goals calculated per the below guidelines, should NOT be applied to the ICU patient. This is associated with no nutritional benefit but a significant increase in the risk of adverse events and complications associated with overfeeding. 1, 2 Table 1 lists some basic guidelines and Table 2 lists vitamin and mineral supplementation recommendations.1-3

Special Considerations

Use caution when evaluating the injured active duty population. Many are young, healthy, and very muscular. If they are muscular with a BMI > 30, you should use their estimated actual weight pre-injury. Those with a BMI > 30 due to obesity should use the IBW when indicated as stated above. Pick any of the above formulas you like as they are all 70–80% accurate compared to a metabolic cart study, which is not available until the patient reaches the U.S. and should be used as soon as possible to obtain the gold standard for caloric and macronutrient requirements.

Role of Hypocaloric Feeding

Although 25-35 kcal/kg/day has been widely utilized as a caloric target when feeding critically ill patients, there has been a growing body of literature that suggests that permissive underfeeding with lower caloric targets is as effective as higher calorie targets and may decrease morbidity from overfeeding or from other adverse effects of delivering a full nutritional load to a metabolically stressed patient. There have been several recently published randomized trials (EDEN and PERMIT)8-10 in mixed critically ill patients and in surgical patients only 11 that have shown equivalent primary outcomes with hypocaloric (10 kcal/kg/day) feeding versus normocaloric (25-35 kcal/kg/day). However, a meta-analysis suggests improvement in some secondary outcome measures with the hypocaloric approach.12 Currently, a hypocaloric approach is a reasonable alternative in patients with low or intermediate nutritional risk (based on NUTRIC or other scoring system) and no pre-existing malnutrition, and may decrease select complications such as feeding intolerance, diarrhea, and high gastric residual volumes. Further, hypocaloric feeding (10-20 kcal/kg) has also been found to have multiple benefits in patients with pre-existing obesity (BMI>30) by reducing excessive fat stores while simultaneously preserving lean body mass. However, it is critical when using a hypocaloric approach in ANY patient to understand than "hypocaloric" refers to non-protein calories, and that it must always be accompanied by full and adequate protein delivery (typically 1.5 to 2 grams/kg ideal body weight).1,2

Formula Selection

- High protein, volume concentrated formula (e.g., IMPACT® or equivalent). A formula with fiber would be contraindicated in patients who are at risk for bowel ischemia or are hemodynamically unstable. 1-3

Use for:

- Major trauma patients for the first 7 days of nutrition support.

- Moderately malnourished patients undergoing major elective procedures of the esophagus, stomach, pancreas, hepatobiliary tree or abdominal-perineal resection

- Severely malnourished patients (pre-albumin < 10gm/dl) undergoing large bowel resection.

- Prolonged starvation > 6 days.

- High output distal small bowel fistula (>500 mL output).

- Burn patients.

- Semi-elemental/elemental enteral formulas (may contain some fiber, moderate protein, and may be supplemented with Omega-3 fatty acids and/or probiotics). Semi-elemental and elemental formulas allow for ease of digestion/absorption. (E.g., Vital®, Vital 1.2 AF®, Vital 1.5®, Peptamen®, Peptamen 1.5®, Peptamen AF® are semi-elemental; Vivonex®, Vital HN®). Use for:

- Proven intolerance to the first formula used

- Persistent, severe diarrhea > 48hrs

- Pancreatic or duodenal injury

- Moderate distention > 24hrs

- Short bowel syndrome

- At discretion of attending physician

- Polymeric, fiber free formula (E.g., Osmolite®1.0, 1.2, 1.5; Nutren® 1.0, 1.5,)—isotonic enteral feed with long-chain proteins, carbohydrates and a normal fat content. Use for:

- Patients with a moderate protein need, normal digestive and absorptive capacity of the GI tract.

- Polymeric with mixed fiber formula (Jevity 1.0, 1.2, 1.5, Fibersource HN, Nutren 1.0 Fiber, Nutrisource Fiber) added fiber content to promote more formed stool. Use for:

- Stable, long term patients and those requiring a bowel regimen (e.g., paraplegics)

- Other formulas include:

- Isosource 1.5—high protein, high calorie, fiber containing formula with 1.5 kcal/ml to limit volume.

- Nepro— volume concentrated (1.8 kcal/mL), lower in K+, Mg, Phos therapeutic nutrition with mixed fiber for patients on dialysis

- Promote, Replete: High protein, polymeric formula, 1.0 kcal/mL. Appropriate for use in patients who tolerate a standard formula but require additional protein and do not need a volume concentrated product.

- Additional fiber source: Use if additional fiber is needed for stool management, use the soluble variety (e.g., Nutrisource Fiber ® or equivalent.)

- Additional protein source: Use if additional protein is needed when calorie needs are already being met by the enteral formula (ex: Beneprotein®, ProMod®, ProStat®). Content of protein varies depending on protein source used.

Enteral Nutrition Initiation and Advancement

Volume-Based and Top-Down Feeding Protocols

Among the many challenges to the delivery of a “goal” dose of enteral calories is the cessation of tube-feeding for procedures, patient “intolerance,” tube dislodgment, diarrhea, transfers, imaging, or other common ICU events. Improved delivery of total caloric goals has consistently been demonstrated through the use of a protocolized approach that aims to minimize interruptions and to empower the bedside caregiver (ICU nurse) to make adjustments to ensure that caloric goals are met. A “volume-based” protocol targets a daily volume of enteral feeding rather than an hourly rate, and allows adjustments in the infusion rate or additional boluses to make up for volume lost when enteral feeds are held or interrupted.1 When initiating and advancing enteral nutrition the following is recommended:

- Start enteral tube feed with full strength formula at 20 ml/hour.

- Increase rate by 20 ml/hour every 6-8 hours to goal rate if low risk for intolerance.

- If high risk for enteral feed intolerance, open abdomen, or known severe ileus, maintain trophic rate (20-30 ml/hr) for first 24 hours, then advance if well tolerated.

- For BURN and HEAD injured patients with no abdominal trauma or other contraindications, advance 20 ml every 4 hours to goal rate.

NOTE: When a patient is transferred from one level of care to the next in a rapid fashion (e.g., Forward Operating Base (FOB) to Role 3 to Role 4 (e.g., Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC)), it is difficult to monitor feeding tolerance during AE or Critical Care Air Transport Team (CCATT) evacuation. It may be best to hold initiation of feeds until patient will be at one location for at least 24 hours. The risk of aspiration in an awake patient or intolerance in an intubated patient is real and necessitates appropriate repeated examinations until feeding tolerance is well established prior to any flights.

Glutamine

In general, glutamine supplementation should not be utilized in the critically ill, including the critically ill combat trauma patient. This represents a major change from the previous CPG.3 Rationale in favor of glutamine supplementation includes that critically ill patients often have decreased glutamine levels upon ICU admission, low plasma glutamine is associated with increased mortality and there are data to suggest that glutamine supplementation may reduce infections complications.1,2,13-15 However, recent evidence indicates that glutamine supplementation significantly increases mortality rates in the critically ill, and particularly those with significant organ dysfunction syndromes.14-16 The role of glutamine supplementation in trauma and burn patients is less clear. Available evidence regarding the benefits of glutamine supplementation in trauma patients is conflicting and a recent meta-analysis regarding enteral glutamine supplementation in trauma patients found no mortality benefit, and a trend towards decreased infectious morbidity.16 We recommend against enteral or parenteral glutamine supplementation in critically ill combat trauma patients. The only population in which glutamine supplementation should be considered is the patient with isolated burn injury and no evidence of sepsis or multiple organ dysfunction.1,16,17 Results of a large multi-center randomized trial (RE-ENERGIZE) are pending and will further guide the use of glutamine supplementation in the burn population once they are available.

Enteral Supplementation For Those Patients Tolerating A Diet

Many traumatically injured patients can tolerate a regular diet. For various reasons, however, patients may be subjected to frequent holding of oral intake for procedures, recovery periods after procedures, decreased appetite due to medications, etc. Supplementation drinks when a patient is eating can help bridge some of the caloric deficits and provide nutritional therapeutic benefits missed during the time-limited periods of inadequate intake.

- Recommended high-protein drinks (e.g., Ensure Plus®, Boost Plus®, Impact© Advanced Recovery™, or equivalent) can be administrated at 0.5–1.0 L per day (2–4 drinks) in addition to meals.

- There is no evidence of benefit of routine enteral supplementation in nutritionally low risk patients with intermittent brief (<48 hours) periods of NPO status.

- For moderate and high nutritional risk patients or pre-existing malnutrition, supplemental oral nutritional intake between NPO periods should be maximized and TPN considered if oral intake is inadequate or evidence of worsening nutritional parameters (e.g., weight loss, decline in pre-albumin, muscle loss).

General Considerations (Gastric Feeds)

General considerations for patients receiving gastric feeds1:

- Gastric feeds may be necessary to initiate early enteral nutrition but are highly discouraged in the combat trauma patient population during the period of rapid transport to CONUS.

- If the clinical scenario warrants consideration of gastric feeding, it must be discussed with the attending trauma surgeon and coordinated among the entire multidisciplinary team.

- Use of pro-kinetic agents to maximize tolerance to enteral feeding should be attempted before cessation of enteral feeding.

- Gastric residual volumes (GRV) may be utilized, but feeding should not be halted for GRV of less than 500 cc.

General Considerations (Jejunal Feed)

General considerations for patients receiving enteral nutrition into the jejunum:

- Maintain head of bed > 30 degrees at all times or in reverse Trendelenburg position if spine not cleared.

- Obtain portable abdominal X-ray within12 hours of any aeromedical movement or transfer to confirm feeding tube location is within jejunum.

- Enteral nutrition administered into the jejunum (past the ligament of Treitz) does NOT need to be stopped prior to going to the operating room, diagnostic tests, CCATT/AE transport, lying flat for procedures, etc.

- Keep OG tube on intermittent low wall suction while initiating and advancing tube feeds via NJFT.

NJFT Maintenance

-

Due to the size (8-12F) of the NJFTs, meticulous care is needed to prevent clogging of tubes. This is easily managed by flushing the tubes every 2 hours, and BEFORE and AFTER all medications given.

-

Clogging is due to either lining of the NJFT with a build-up of tube feeds or inappropriate medications given down the tube.

-

The volume of the tube is so small that no amount of pancreatic enzymes, bicarbonate, cola, etc. is effective to maintain patency for any extended period of time. Prevention of the buildup is essential to ensure a functioning tube.

-

Recommend flush feeding tube with 20 ml water (may also use pre-filled NS syringes) every two hours. Flush an additional 20 ml BEFORE and AFTER all medications are given. The volume may be increased if patient’s condition and fluid requirements dictate.

-

For patients who are estimated to require prolonged enteral feeding (>4 weeks) or who are unable to tolerate or maintain a nasoenteric tube, placement of a surgical feeding tube is strongly encouraged if no absolute contraindication is present. For patients requiring prolonged enteral feeding access a gastrostomy tube is preferred over a jejunostomy for ease of management, routine care, and conversion to a simplified bolus tube-feeding regimen.

General Considerations (Parenteral Nutrition)

-

TPN is generally unavailable in a combat zone.

-

Only utilize TPN when enteral nutrition is not possible or is inadequate to meet the minimal estimated caloric requirements.1

-

General initial TPN orders: 20-25 kcals/kg. Initial Dextrose of 150 g if diabetic, 200 g if not diabetic. Increase by 50 g/day if good glycemic control. Glucose infusion rate of 2-3 mg/kg/min initially. IV-Lipids of no more than 1 g/kg/d. Hold IV lipids if TG > 400 mg/dL. Provide trace elements only 1-2x/wk if total bilirubin is > 4 mg/dL.

-

Ensure patient has a clean, dedicated central line or peripherally-inserted central catheter (PICC) for administration of TPN.

-

A 0.2 micron in-line filter should be used with non-lipid containing TPN, and a 1.2 micron filter used with any lipid-containing TPN.

Medication Considerations

Inotropic agents (E.g., Dobutamine, Milrinone)

No change to feeding plan recommended. Advance per feeding protocol.

Paralytics, Vasoactive Agents

(Includes but not limited to: e.g., vasopressin > 0.04 units/min, dopamine > 10 mcg/kg/min, norepinephrine > 5 mcg/min, phenylephrine > 50mcg/min, any epinephrine)

-

Elemental formula at 20 ml/hr – do not advance.

-

Consider TPN starting post injury day number 7 if enteral feeds are not tolerated or not tolerated at the goal rate.

-

Consider early initiation of TPN in high nutritional risk score or pre-existing malnutrition patients.

-

Hold enteral feeding if adding vasopressor, increasing dosages of vasopressors, or persistent MAP < 60 mmHg.

Laboratory Evaluation

-

Obtain a pre-albumin every Monday for those with ICU stays greater than 7 days.

-

Obtain liver function tests (LFTs) and lipid panels at baseline and every Monday for those on TPN.

Enteral Nutrition Intolerance Management

(See Appendix A)

Vomiting

- If no OG/NG tube in position, place one and initiate low wall suction.

- Check existing OG/NG tube function and placement location.

- If OG/NG tube is in proper position and functional, decrease tube feed rate by 50% and notify physician for further evaluation and work up.

- Ensure patient is having normal bowel elimination.

- If the patient is receiving gastric enteral feeding, consider placing the feeding tube post-pyloric.

Abdominal Distension (Mild to Moderate)

- Perform history and physical exam.

- Maintain current tube feed rate and do not advance.

- Obtain portable abdominal x-ray to assess for small bowel obstruction or ileus.

- Ensure patient is on bowel regimen to avoid constipation.

- If distention persists >24hrs with no contraindication for continued tube feeds, switch to elemental formula.

- If feeding while the patient is on low-dose vasopressors, any increase in distention should prompt holding tube feeds and consideration of bowel ischemia.

Severe

- Perform history and physical exam.

- Stop tube feed infusion.

- Monitor fluid status.

- Consider workup—CBC, lactate, ABG, Chem7, KUB, CT scan abdomen.

- Check bladder pressure.

Diarrhea

- If the patient develops Moderate (3–4 times/24 hrs or 400–600ml/24hrs) to severe diarrhea (>4 times/24hrs or > 600ml/24hrs) consider the following:

- Review medication record for possible causes of new onset diarrhea.

- Obtain abdominal x-ray to evaluate feeding tube location.

- Consider working up patient for Clostridium difficile (C. diff.) infection. If evidence of C. diff. infection, treat with oral metronidazole or oral Vancomycin depending on severity. If utilized, antidiarrheal medications should be administered with great caution in the patient with C. diff. and should only be considered in the patient with a controlled or improving C. diff. infection.

- Monitor fluid and electrolyte status.

- Consider starting a soluble fiber supplement (e.g., guar gum, provide 1 pkg BID, increase to 1 pkg QID if stool consistency does not improve in 2-3 days).

- If there is no evidence of C. diff. infection, consider giving 2 mg loperamide after each loose stool. An alternative is codeine 15 mg.

High OG/NG tube output

(> 1200 ml/24 hrs) with OG/NG tube to continuous suction and feeding via NJFT.

- Stop tube feeds.

- Obtain abdominal x-ray to determine location of OG/NG tube and NJFT.

- Verify OG/NG tube is in the stomach. If tube is past pylorus, pull it back into stomach and resume tube feeds at previous rate.

- Verify NJFT is in correct position. If NJFT is in the stomach take appropriate action to move the tube to the appropriate position. If NJFT is in the correct position, decrease tube feeds by 50% and assess patient’s overall condition.

- Check NG/OG tube aspirate for glucose testing in lab.

- If glucose > 110, hold tube feeds for 12 hours and re-evaluate.

- If glucose negative, resume tube feeds at 50% previous rate.

Increased Gastric Residual Volumes (GRV)

(With gastric or post-pyloric feeding)

- If feeding through OG/NG tube, or if additional OG/NG tube in place (NJFT or post-pyloric feeding tube) check gastric residuals every 4-8 hours.

- Ensure no evidence of new ileus (i.e. lack of bowel regimen, electrolyte abnormalities, recent abdominal operation, abdominal compartment syndrome, C. diff infection etc.) or bowel obstruction.

- Re-infuse the entire gastric aspirate or administer an equivalent volume of ½ normal saline.

- If GRV > 300 ml on two consecutive checks, notify physician.

- Start Erythromycin 250 mg IV or oral every 6 hours or metoclopramide 10 mg IV every 6 hours and continue every 4 hour residual checks.

Hold enteral feeds only when ordered by physician.

Bowel Regimen

Those patients at high risk for acute constipation should be started on a bowel regimen. If a patient is receiving tube feeds and has less than one Bowel Movement (BM) every two days, they should be started on the bowel care protocol. A bowel care protocol also may be started empirically with initiation of enteral nutrition in patients know to be at risk for constipation.

Acute Constipation

Inclusion criteria for patients at high risk for acute constipation:

- Opioids

- Immobility

- Altered diet and fluid intake

- Stress

- History of constipation

Relative Contraindications

- Rectal surgery

- Abdominal pain

- Allergy to bowel regimen medications

- Neutropenia (ANC < 1000/mm3)

- Thrombocytopenia (platelets < 30,000)

Absolute Contraindications

Suspected or confirmed bowel obstruction

NOTE: If patient has had one BM every two days, patient is at Stage One or under observation only.

Stage One

(If no bowel movement for 48 hours)

Patient assessment and rectal exam

- Impacted: Manually dis-impact; give soap suds enema once OR Bisacodyl 10 mg suppository once daily

- Not impacted: Docusate 100 mg PO or NJFT q 8 hours and Senna 1 tab PO or 5ml via NJFT every am

- If no BM or very small amounts in 24 hours following initiation of Stage One, proceed to Stage Two.

Stage Two

- Add Bisacodyl 10 mg supp once daily, hold if stooling and continue with Stage One regimen.

- If no BM or very small amounts within 24 hours, proceed to Stage Three.

- If patient develops loose stools or diarrhea, return to Stage One.

Stage Three

- Add Milk of Magnesia 30 ml PO every 6 hours or Miralax 17 grams PO/NJFT twice daily until BM, then stop (avoid Milk of Magnesia if renal insufficiency is present). Return to Stage Two.

- If no BM in 24 hours or very small amounts, proceed to Stage Four.

- If patient develops loose stools or diarrhea, return to Stage One.

Stage Four

- Call and notify MD.

- Obtain an abdominal x-ray.

- Clarify continued therapy for bowel care.

Fecal Management System

For patients requiring the use of Fecal Management System (FMS) for wound care and/or stool management, please refer to manufacturer’s instructions for use. FMS should only be used with the approval of the patient’s attending surgeon.

Performance Improvement (PI) Monitoring

Intent (Expected Outcomes)

All patients undergoing laparotomy within 24-48 hours of admission to a Role 3 facility who meet criteria for enteral feeding will have a NJFT placed at the time of surgery

Performance/Adherence Measures

All patients requiring laparotomy within 24-48 hours of admission to a Role 3 facility who also met criteria for enteral feeding had the NJFT placed at the time of surgery.

Data Source

- Patient Record

- Department of Defense Trauma Registry (DoDTR)

System Reporting and Frequency

The above constitutes the minimum criteria for PI monitoring of this CPG. System reporting will be performed annually; additional PI monitoring and system reporting may be performed as needed.

The system review and data analysis will be performed by the Joint Trauma System (JTS) Director and the JTS Performance Improvement Branch.

Responsibilities

It is the trauma team leader’s responsibility to ensure familiarity, appropriate compliance and PI monitoring at the local level with this CPG.

References

- Taylor BE, McClave SA, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, McCarthy MS, Davanos E, Rice TW, Cresci GA, Gervasio JM, Sacks GS, Roberts PR, Compher C; Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.).Crit Care Med. 2016;44 (2): 390-438.

- Critical Care Nutrition. Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines 2015. 2015 http://www.criticalcarenutrition.com/docs/CPGs%202015/Summary%20CPGs%202015%20vs%202013.pdf. Accessed 30 September 2015.

- Joint Trauma System Clinical Practice Guideline: Nutrition Support of the traumatically injured patient. June 2012. http://www.usaisr.amedd.army.mil/cpgs.html. Accessed 27 July 2015.

- Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Jiang X, Day AG. Identifying critically ill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: the development and initial validation of a novel risk assessment tool. Critical Care. 2011;15 (6):R268 .

- Chung CK, Whitney R, Thomphson CM, et al. Experience with an Enteral-Based Nutritional Support Regimen in Critically-Ill Trauma Patients. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217 (6)1-18.

- Davies AR, Morrison SS, Bailey MJ, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing early nasojejunal with nasograstric nutrition in critical illness. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2342-2348.

- McClave SA, Martindale RG, Vanek VW, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009 May-Jun;33(3):277-316.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, et al. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury. JAMA 2012;307:795-803.

- Arabi YM, Aldawood AS, Haddad, SH, et al. Permissive Underfeeding or Standard Enteral Feeding in Critically Ill Adults. NEJM 2015;37:2398-408.

- Yaseen MA, Aldawood AS, Haddad SH, et al. Permissive underfeeding or standard enteral feeding in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2398-408.

- Charles EJ, Petroze RT, Metzger R. Hypocaloric compared with eucaloric nutritional support and its effect on infection rates in a surgical intensive care unit: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:1337-43.

- Marik PE, Hooper MH. Normocaloric versus hypocaloric feeding on the outcomes of ICU patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2015 Nov 10. [Epub ahead of print].

- Labow BI, Souba WW. Glutamine-therapeutic usage and analysis of glutamine metabolism. World J Surg. 2000;24:1503-1513.

- Heyland D, Muscedere J, Wischmeyer PE, et al. A randomized trial of glutamine and antioxidants in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1489-97.

- van Zanten AR, Sztark F, Kaisers UX, et al. High-protein enteral nutrition enriched with immune-modulating nutrients vs standard high-protein enteral nutrition and nosocomial infections in the ICU: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:514-524.

- van Zanten AR, Dhaliwal R, Garrel D, Heyland DK. Enteral glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2015;19:294.

- Garrel D, Patenaude J, Nedelec B, et al: Decreased mortality and infectious morbidity in adult burn patients given enteral glutamine supplements: a prospective, controlled, randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med 2003; 31:2444–2449

- Nathens A, Neff M, Jurkovich G, Klotz P, et al. Randomized, prospective trial of antioxidant supplementation in critically ill surgical patients. Ann Surg. 2002;236:814-822.

- Moore FA, Moore EE, Kudsk KA, et al. Clinical benefits of an immune-enhancing diet for early post-injury enteral feeding. J Trauma. 1994;37:607-615.

- Collier BR, Giladi A, Dossett LA, et al. Impact of high-dose antioxidants on outcomes in acutely injured patients. JPEN. 2008;32 (4):384-388.

Appendix D: Additional Information Regarding Off-Label Uses In CPGS

Purpose

The purpose of this Appendix is to ensure an understanding of DoD policy and practice regarding inclusion in CPGs of “off-label” uses of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products. This applies to off-label uses with patients who are armed forces members.

Background

Unapproved (i.e., “off-label”) uses of FDA-approved products are extremely common in American medicine and are usually not subject to any special regulations. However, under Federal law, in some circumstances, unapproved uses of approved drugs are subject to FDA regulations governing “investigational new drugs.” These circumstances include such uses as part of clinical trials, and in the military context, command required, unapproved uses. Some command requested unapproved uses may also be subject to special regulations.

Additional Information Regarding Off-Label Uses in CPGs

The inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is not a clinical trial, nor is it a command request or requirement. Further, it does not imply that the Military Health System requires that use by DoD health care practitioners or considers it to be the “standard of care.” Rather, the inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is to inform the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner by providing information regarding potential risks and benefits of treatment alternatives. The decision is for the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner within the practitioner-patient relationship.

Additional Procedures

Balanced Discussion

Consistent with this purpose, CPG discussions of off-label uses specifically state that they are uses not approved by the FDA. Further, such discussions are balanced in the presentation of appropriate clinical study data, including any such data that suggest caution in the use of the product and specifically including any FDA-issued warnings.

Quality Assurance Monitoring

With respect to such off-label uses, DoD procedure is to maintain a regular system of quality assurance monitoring of outcomes and known potential adverse events. For this reason, the importance of accurate clinical records is underscored.

Information to Patients

Good clinical practice includes the provision of appropriate information to patients. Each CPG discussing an unusual off-label use will address the issue of information to patients. When practicable, consideration will be given to including in an appendix an appropriate information sheet for distribution to patients, whether before or after use of the product. Information to patients should address in plain language: a) that the use is not approved by the FDA; b) the reasons why a DoD health care practitioner would decide to use the product for this purpose; and c) the potential risks associated with such use.