Management of COVID-19 in Austere Operational Environments (Prehospital & Prolonged Field Care)

Joint Trauma System

Management of COVID-19 in Austere Operational Environments

This practice management guide does not supersede DoD Policy. It is a guideline only and not a substitute for clinical judgment.

It is based upon the best information available at the time of publication. It is designed to provide information and assist decision making. It should not be interpreted as prescribing an exclusive course of management. It was developed by experts in this field. Variations in practice will inevitably and appropriately occur when clinicians take into account the needs of individual patients, available resources, and limitations unique to an institution or type of practice.

Every healthcare professional making use of this guideline is responsible for evaluating the appropriateness of applying it in the setting of any particular clinical situation.

Leads: MAJ William E. Harner, MC, USA; LTC Sean C. Reilly, MC, USA Special thanks to Respiratory Therapists at Landstuhl Regional Medical Center. Special thanks to Flight Paramedics and ECC Nurses at Fort Rucker, Alabama. Special thanks to the TCMC training faculty at Fort Sam Houston, Texas

CDR Mark T. Andres, MC, USN

MAJ Paul J. Auchincloss, SP, USA

MAJ Melanie Bowman, AN, USA

MAJ Nathan L. Boyer, MC, USA

MAJ Daniel B. Brillhart, MC, USA

Lt Col Daniel J. Brown, USAF, MC

LTC Gregory Brown, MC, USA

CDR R. Christopher Call

LTC Brian M. Cohee, MC, USA

LTC Robert J. Cornfeld, MC, USA

LTC Matthew D’Angelo, AN, USAR

CPT William T. Davis, USAF, MC

MAJ Steven Deas, USAF, MC

MAJ Thomas Frawley, MC, USA

LTC David C. Hostler, MC, USA

CPT Jacob James, AN, USA

MAJ John Jennette, MC, USA

SFC Dennis M. Jarema, 18D/RN, ARNG

MAJ Scott R. Jolman, SP, USA

Maj Tyler Kallsen, USAF, MC

COL(ret) Sean Keenan, MC, USA

SFC Paul E. Loos, 18D, USA

LCDR Andrew J. Obara, MC, USN

Maj Timothy R. Ori, USAF, MC

COL Jeremy C. Pamplin, MC, USA

LTC Douglas F. Powell, MC, USAR

SFC Justin C. Rapp, 18D, USA

LTC Sean C. Reilly, MC, USA

LTC(P) Jamie C. Riesberg, MC, USA

MAJ(ret) Nelson Sawyer, SP, USA

LCDR Nathaniel J. Schwartz, MC, USN

MAJ Janet J. Sims, AN, USA

SO1 Michael Stephens, USN

MAJ Mary Stuever, USAF

MAJ Michal J. Sobieszczyk, MC, USA

COL Brian Sonka, MC, USA

CPT Erick E. Thronson, AN, USA

MAJ(ret) William N. Vasios, SP, USA

COL (ret) Matthew Welder, AN, USA

COL Ramey Wilson, MC, USA

COL(ret) Sean Keenan, MC, USA

SFC Paul E. Loos, 18D, USA

LCDR Andrew J. Obara, MC, USN

Maj Timothy R. Ori, USAF, MC

COL Jeremy C. Pamplin, MC, USA

LTC Douglas F. Powell, MC, USAR

SFC Justin C. Rapp, 18D, USA

LTC Sean C. Reilly, MC, USA

COL Jamie C. Riesberg, MC, USA

MAJ(ret) Nelson Sawyer, SP, USA

LCDR Nathaniel J. Schwartz, MC, USN

MAJ Janet J. Sims, AN, USA

MAJ Michal J. Sobieszczyk, MC, USA

COL Brian Sonka, MC, USA

SO1 Michael Stephens, USN

MAJ Mary Stuever, USAF

CPT Erick E. Thronson, AN, USA

MAJ(ret) William N. Vasios, SP, USA

COL (ret) Matthew Welder, AN, USA

COL Ramey Wilson, MC, USA

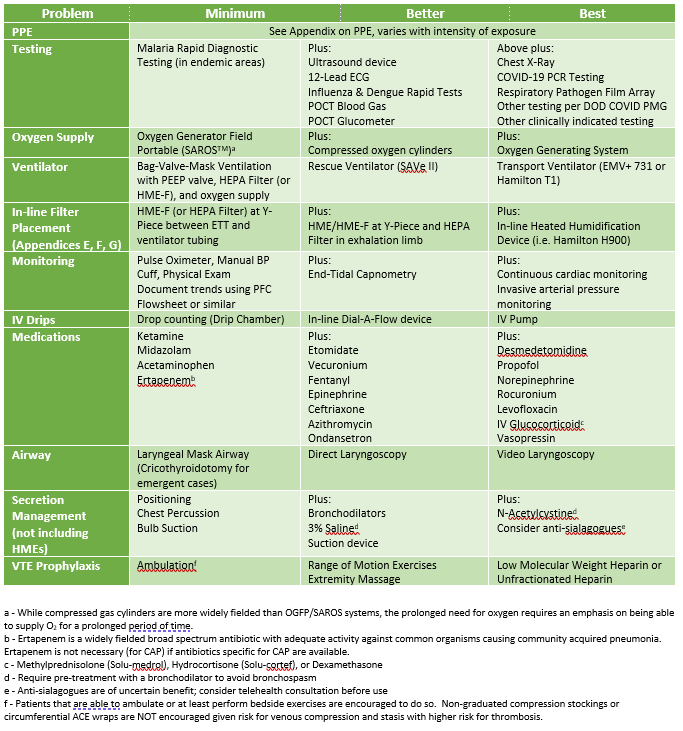

This guideline is intended for the provider operating in an austere, limited resource setting. Providers have varying levels of knowledge, training, and experience in basic critical care concepts. It is not intended to be all inclusive, but to spur further thinking and identify areas where resource limitations or known diseases specify changes to usual practices. The management strategy described is designed for a 24-hour hold of a single critically ill patient and is tailored to the equipment and medications typically available in austere operational settings (Role 1 and Expeditionary Role 2). Refer to the most updated DoD COVID-19 Practice Management Guide for recommended clinical management, and CENTCOM COVID-19 Playbook for operational considerations.

- 1) Our primary mission remains the same. We must maintain the ability to provide damage control resuscitation and surgery in support of combat operations.

- 2) Prevention of disease transmission to medical personnel is a mission critical consideration for austere teams as there is generally very limited skill redundancy.

- 3) Primary capability limitations may include manpower, oxygen supply, ventilators, medications, and personal protective equipment (PPE).

- 4) Care of the critically ill COVID-19 patient is primarily supportive medical care plus appropriate disease transmission precautions.

- 5) Use of telemedicine to push critical care expertise as far forward as possible should be part of the operational plan.

- 1) Most providers operating in austere locations have equipment geared towards combat casualty care, not necessarily care for patients in severe respiratory failure.

- 2) Oxygen supply is generally limited to a few portable oxygen tanks and oxygen concentrators not designed to provide high volume oxygen support.

- 3) Laboratory and radiologic evaluation capabilities are generally limited to non-existent.

- 4) Local and international supply lines have been significantly affected by COVID-19, with reduced resupply or delivery of disease specific supplies (e.g., testing kits and viral filters).

- 5) Time to medical evacuation may be significantly prolonged given the global nature of this crisis, lockdown over sovereign airspaces, and the need to limit impact to military air assets.

- 6) Most austere locations consist of relatively small camps (usually less than 100-300 personnel) with primarily younger, healthier populations. However, some personnel may fall into high risk categories. As such, based upon current epidemiology, planning should account for 1-3 critically ill patients at each austere location.

- 1) Quarantine: Separation and restriction of movement (ROM) for personnel potentially exposed to a contagious disease but without symptoms of illness. These personnel may have been exposed to a disease and do not know it, or they may have the disease but do not show symptoms. This is a command function that is medically supported.

- 2) Isolation: Separation of sick personnel with a confirmed contagious disease or high index of suspicion (i.e. person under investigation) from people who are not sick. This is a medical function requiring command support.

- 3) Person Under Investigation (PUI): A patient with signs and symptoms consistent with COVID-19 infection and possible exposure to the virus. In areas where COVID-19 is already widespread, symptoms alone may make the diagnosis of “PUI.” All PUIs must be isolated.

- 4) Contact Spread: Spread of disease via direct contact with an infected patient or contaminated surface. Contact precautions aim to mitigate this method of transmission.

- 5) Droplet Spread: Spread of disease via relatively large liquid particles that settle from the air, typically within a few feet. Droplet precautions aim to mitigate this method of transmission.

- 6) Airborne Spread: Spread of disease via small liquid particles (aerosols) that remain aloft for prolonged periods of time and may travel longer distances. Airborne precautions aim to mitigate this method of transmission.

- 1) Alhazzani W, Hylander M, Arabi Y, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Guidelines on the Management of Critically Ill Adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Crit Care Med. First published June 2020.

- 2) Brewster DJ, Chrimes N, Do T, et al. Consensus Statement: Safe Airway Society principles of airway management and tracheal intubation specific to the COVID-19 adult patient group. Medical Journal of Australia. Published on-line ahead of print 8 Dec 2020. Published on-line ahead of print 01 May 2020.

- 3) Interim U.S. Guidance for Risk Assessment and Work Restrictions for Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure to COVID-19. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 14 December 2020.

- 4) Matos RI, Chung L. DoD COVID-19 Practice Management Guide: Clinical Management of COVID-19. Defense Health Agency. Updated 3 March 2021.

- 5) Stuever M, Hydrick A, Meza P, Funari T, et al. U.S. Central Command COVID-19 Pandemic Playbook for Operational Environments. Published 23 April 2021.

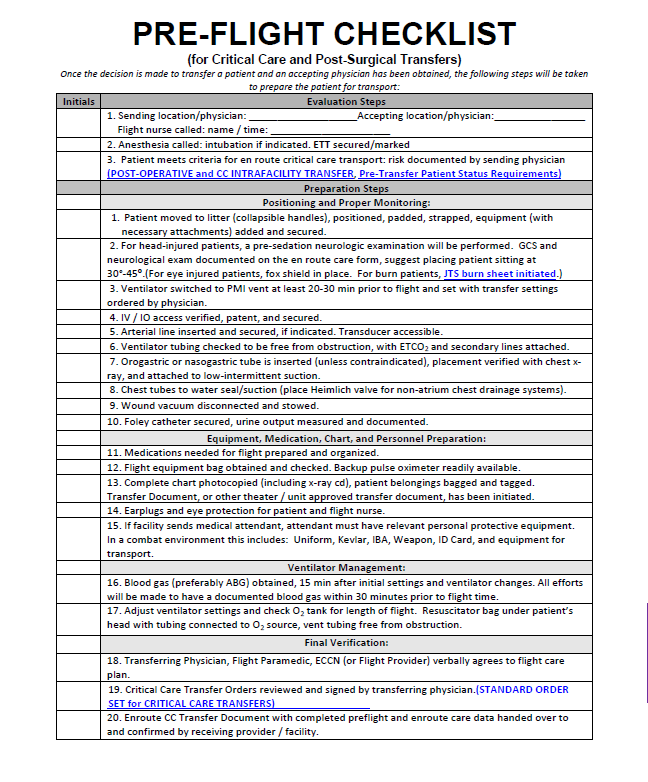

- 6) S. Army School of Aviation Medicine. Critical Care Flight Paramedic. Standard Medical Operating Guidelines (CY20 Version). Published 10 October 2020.

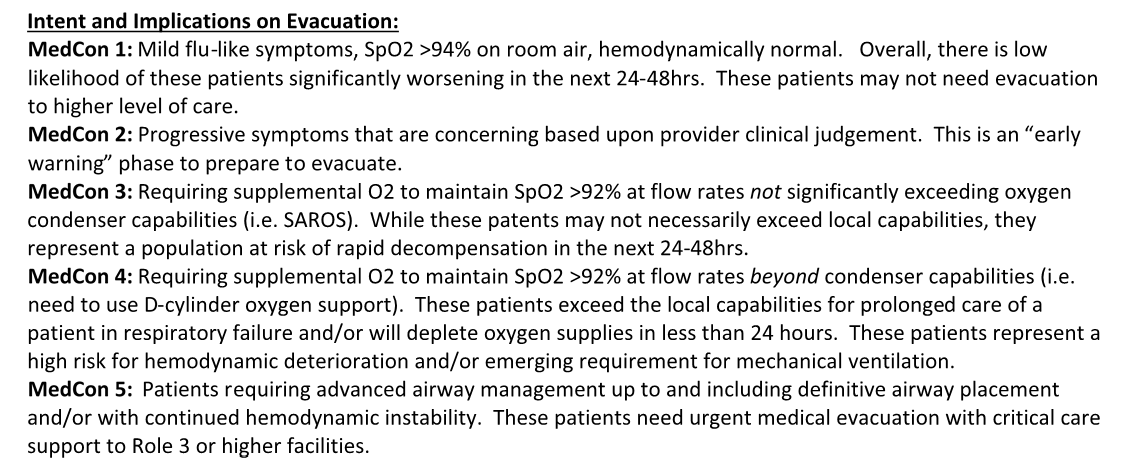

- 1) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends enhanced droplet precautions. Cover mucosal surfaces (eyes, nose, and mouth) and provide skin contact precautions.

- 2) N95 masks DO NOT work properly with facial hair; shaving is strongly recommended for anyone participating in direct patient care.

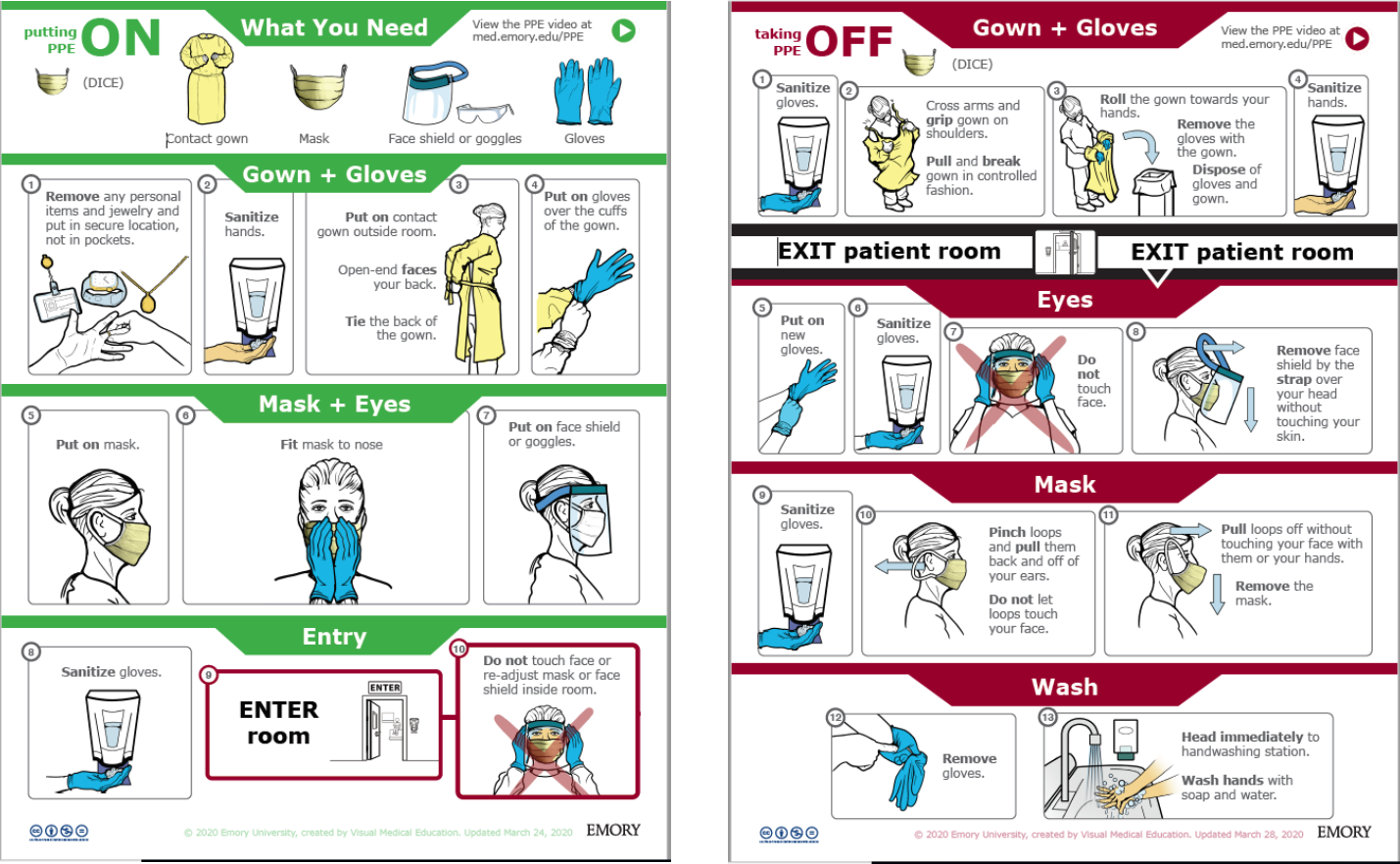

- 3) Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) should be donned/doffed per CDC instructions and following proper techniques to minimize the risk of self-inoculation.

- 4) If possible, have a trained observer watch donning and doffing to guard against accidental exposure of medical personnel.

- 5) The following procedures carry a significantly higher risk of virus aerosol formation:

- Tracheal Intubation

- Extubation (accidental or planned)

- Bag-Valve Mask Ventilation

- Any disconnection of the ventilator circuit

- Tracheal suctioning without in-line suction device

- Tracheostomy (and Cricothyroidotomy)

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Levels of PPE

Levels are based upon risk of disease and risk of procedure. NOTE: the patient should wear a basic facemask (cloth or otherwise) whenever feasible to provide an additional barrier.

Minimum: Face covering, eye protection glasses, gloves, and makeshift gown. NOTE: For patients with low probability of disease and where direct contact with the patient is low, gowns may not be required (mirroring conventional droplet precautions).

Better: Surgical mask or N95 mask, face shield (either standalone or with mask) and eye protection, gloves, gown (surgical or contact), head covering.

Best: N95 mask (with or without surgical mask covering) with face shield and disposable head covering or hooded face shield (e.g., Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and high yield Explosives (CBRNE) pro-mask) along with gown and gloves.

Conservation of PPE

- 1) COVID-19 can survive on various surfaces for up to 72 hours or longer.

- 2) Use cloth face covering when risk is low to conserve supply of surgical face masks and N95 masks needed for high risk procedures (e.g., endotracheal intubation).

- 3) Doff PPE in a manner that allows for it to be easily donned again without contacting contaminated surfaces (if possible).

- 4) For re-use of surgical face masks or N95 masks: while wearing gloves, store the mask in a paper bag in a dry, shaded/indoor area for 72 hours prior to using again. DO NOT use bleach or UV radiation (i.e. sunlight) to ‘sterilize’ the N95 – this will degrade mask effectiveness.

- 5) Eye protection glasses and face shields should be cleaned with a diluted bleach solution between uses.

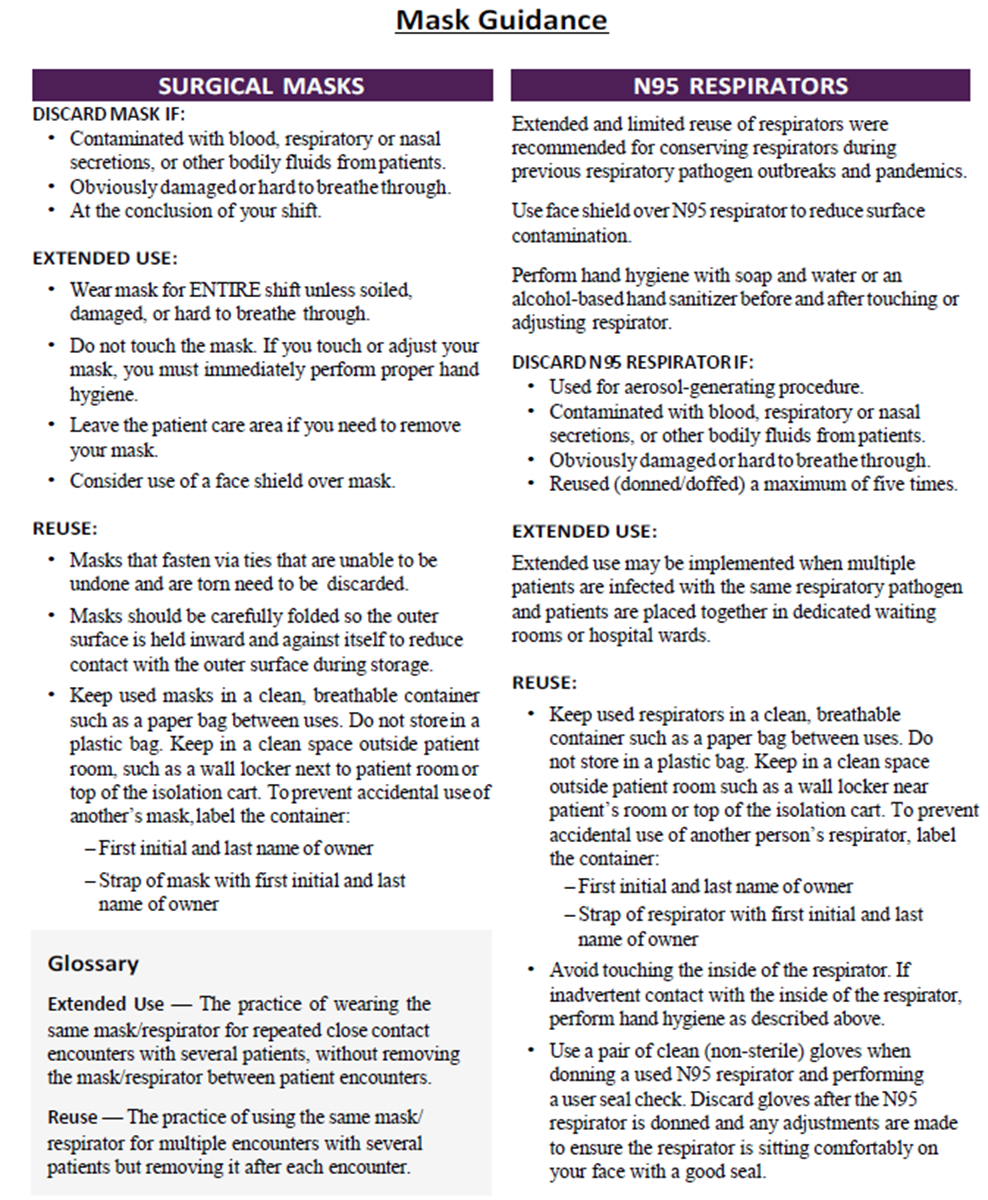

Mask Recommendations

U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommends the following for extended use and re-use of N95 respirators:

- 1) N95 masks maintain their effectiveness for at least 8 hours of continuous or intermittent use.

- 2) N95 masks should be discarded following aerosol generating procedures (e.g., endotracheal intubation) or when visibly contaminated with bodily fluids.

- 3) Consider using a large face shield that sits in front of the mask, wear a surgical mask over-top of the N95, or masking the patient to minimize contamination.

- 4) Perform hand hygiene with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand sanitizer before and after touching or adjusting the mask.

- 1) While separate berthing for quarantined individuals is optimal, living space is generally limited in austere settings. As such, berthing with individual rooms should provide adequate protection to allow quarantined individuals to remain in their room.

- 2) Individuals placed on quarantine per CDC screening guidelines are instructed to stay in their room and conduct self-observation for the development of any symptoms.

- 3) Teammates should check on the status of the quarantined individual several times daily and bring them food, water, and comfort items as needed.

- 4) Social distancing is strictly enforced when the individual needs to use the bathroom for toilet and hygiene. They should not use the gym, MWR, or any other common areas while under quarantine.

- 5) Depending on risk to force and mission requirements, mission critical personnel (including medical personnel) could be allowed to work (face covering, N-95 if possible, otherwise a cloth mask may be used). Early engagement of nonmedical leadership in such decision making is essential.

- 1) PUI may not leave isolation berthing unless instructed to do so by medical personnel.

- 2) When outside of the isolation berthing, PUI will be required to wear a cloth face covering and clean hands with soap and water or alcohol based hand sanitizer.

- 3) No visitors allowed within the isolation berthing.

- 1) Pre-designate a provider as the COVID provider. This provider should perform all evaluations and procedures to limit exposure to other medical personnel, if possible. Remember, maintaining combat casualty care capability is still the priority. Balance the provider skillset and experience with potential impact on medical support for combat operations. The designated provider may not be the most experienced provider, but can consult with teammates as needed for management, procedures, and nursing care.

- 2) All patients presenting to sick call with any complaint should be screened for typical COVID-19 symptoms (fever, cough, dyspnea, gastrointestinal complaints) and risk of exposure.

- 3) If PUI presents to a provider other than the designated COVID attending provider, the patient should be provided a cloth face covering (or surgical mask) and escorted to pre-designated COVID treatment area.

- 4) If possible, all evaluations and treatment of PUI should be done outside the combat casualty care facility to mitigate potential for contamination of the facility.

- 5) Medical personnel performing the evaluation should wear the best available PPE (see Appendix B) balancing the supply of PPE with the threat of patient interaction.

- 6) Examination should include full vital signs including pulse oximetry, work of breathing assessment, pulmonary auscultation, skin temperature, and capillary refill.

Ancillary Tests

Minimum: Rapid Malaria Testing (if febrile in malaria endemic region)

Better (Above +):

- 12-Lead ECG

- Rapid Flu Testing

- Rapid Dengue Testing

- I-STAT arterial blood gas or venous blood gas

- Ultrasound (cardiac and pulmonary)

Best (Above +):

- PA and LAT Chest Films

- Respiratory Pathogen Film Array (i.e. Biofire)

- COVID-19 PCR Testing

- Other laboratory testing listed DoD COVID19 Practice Management Guide

Identifying Patients at Risk for Deterioration:

- 1) Among patients with mild to moderate symptoms and normal resting pulse oximetry, the risk of deterioration is increased in those presenting with dyspnea, desaturation on exercise testing, and epidemiologic risk factors for severe disease (age over 50, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, immunosuppressive medications). These patients should be monitored closely and considered for early evacuation.

- 2) Exercise (Walk) Test: Have the patient jog or walk in place for 3 minutes. Inability to complete the test or desaturation below SpO2 <94% confers a higher risk for clinical deterioration. This is a triage test used by several New York hospitals during the pandemic to help gauge the need for closer monitoring.

Consideration of Alternative Diagnoses

- 1) If a patient with symptoms possibly consistent with COVID-19 has known risk for or exposure to COVID-19, the patient should be managed as a PUI regardless of the differential diagnosis. This does not mean that alternative and/or comorbid diagnoses are impossible as COVID-19 patients can be co-infected with other pathogens.

- 2) Life threatening alternative diagnoses (e.g., pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, acute myocardial infarction, etc.) should always be considered and managed according to standard practices for diagnosis and treatment.

Testing in Austere Locations

- 1) Most austere locations will be unable to test for COVID-19 using an approved polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay. However, if testing does become available, the following should be considered:

- The false negative rate for COVID-19 PCR assay is likely to be significant enough to merit a minimum period of isolation (or quarantine) regardless of test result.

- Testing priority should be guided by the CDC priority for testing balanced against operational priorities. For example, a patient with mild symptoms and no risk factors for decompensation may not warrant immediate testing. However, if combatant command determines that the individual is mission critical, the testing may be considered a higher priority.

- 2) Given significant resource constraints in an austere environment (specifically the limited duration of oxygen supply, medication supply, and limited quantity of PPE) coordination for evacuation to the appropriate level of care should be initiated as soon as possible, even if the patient does not necessarily need urgent evacuation as it may take more than 24 hours to execute an evacuation mission. This underscores the importance for early evacuation coordination while simultaneously planning for prolonged care.

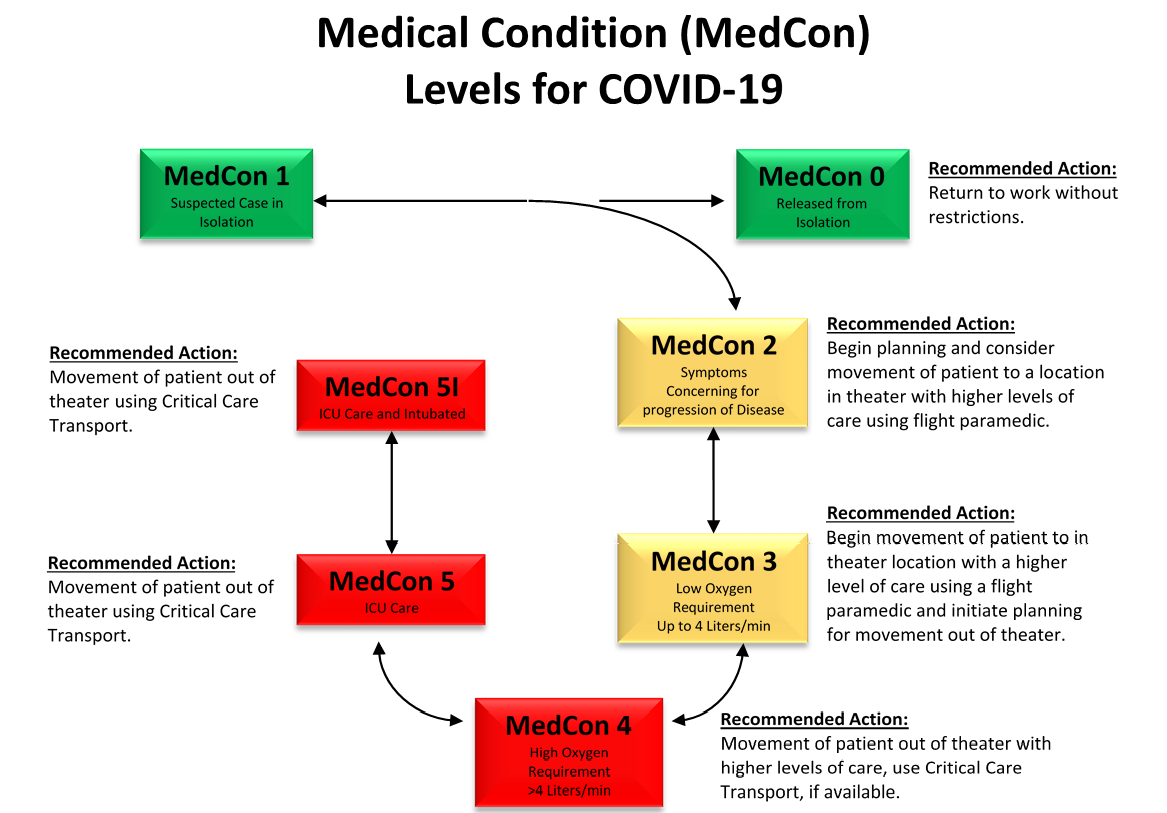

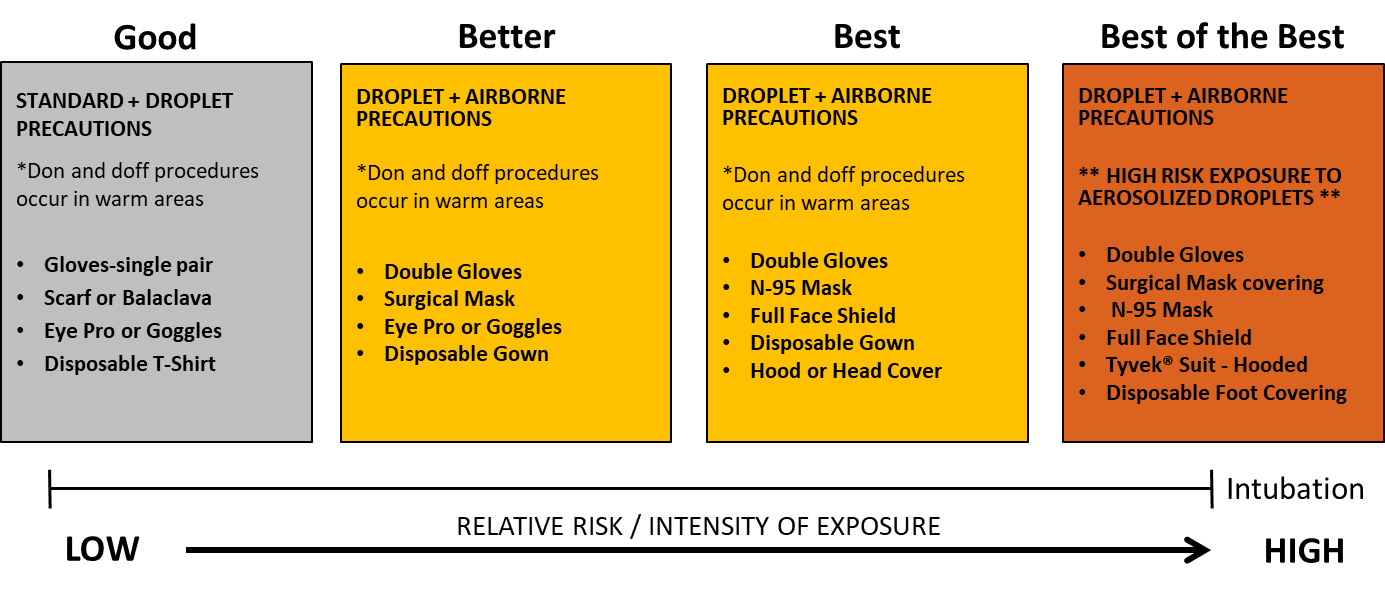

- 3) Appendix A describes a tiered Medical Condition (MedCon) flowchart developed for standardization of terminology across an area of responsibility (AOR) and between medical providers, medical planners, and operational leadership.

- 1) Most austere locations have group billeting with shared ventilation, making the practice of ‘self-isolation’ impractical. While individual billeting with separated bathrooms is optimal, patient isolation cohorts may be the best option available with limited space.

- 2) Billeting should be able to expand to hold multiple patients of varying severity and allow adequate comfort for all patient categories (mild, moderate, and severe illness).

- 3) Billeting ventilation (i.e. environmental control units) should face away from any gathering areas and common walkways.

- 4) Billeting entrances should be well marked (e.g., “Isolation Area - No Unauthorized Access!”) and include posted guides on proper PPE procedures.

- 5) Consider location relative to bathrooms and areas traversed to get to the bathrooms. If available, designate bathrooms for isolated patients only. If there is engineering support, a pit toilet can be constructed. Disposable water bottles can be used as urinals.

- 6) Consider designating a critical care area within or near the isolation area separate from the main medical facility/aid station. Additionally, consider the route that must be traversed in order to transport the patient to an evacuation platform. The focus should be, as much as possible, on preserving the ability to provide combat casualty care, if needed.

- 7) If confirmatory testing is available, considering cohorting isolated patients by positive test vs. untested or negative test to avoid needlessly infecting PUIs who do not in-fact have COVID-19.

- 1) Do not move PUI into isolation billeting before preparation is complete.

- 2) All non-isolated personnel occupying the space must vacate the building.

- 3) Allow PUI (while wearing a surgical mask) to gather personal belongings from lodging and move into isolation berthing.

-

- Personal hygiene items

- Bed sheets and clothing

- Electronic devices + chargers

- 4) If PUI is unable to retrieve items, personnel with mask + gloves (at minimum) should retrieve any essential items.

- 5) Basic medical items remain in isolation billeting at all times:

-

- Oral thermometer with box of sheaths

- Pulse oximeter(s)

- Alcohol based hand sanitizer

- Stethoscope(s)

- Manual blood pressure cuff(s)

- Box of surgical masks

- 14 day supply of Acetaminophen, ibuprofen and cold/flu medicine as available.

- 6) PPE Box (for providers, prepositioned outside isolation berthing):

-

- Min 3 gowns (either surgical or yellow contact precaution gowns)

- Min 3 N95 masks

- Min 6 surgical masks

- Min 3 face shields and/or cleaned eyepro

- Min 3 surgical caps or bouffant caps

- Box of gloves

- Tub of disinfectant wipes

- Spray bottle of dilute bleach

- Paper towels (for cleaning)

- Trash bags

- 7) Life Support Items

-

- Hydration: Water bottles, juice containers, Gatorade, etc.

- Food: MREs, meal supplement drinks, snacks, etc. Provide hot-meals as able.

- Hygiene: Box of wet wipes. Encourage use of portable urinals (e.g., empty water bottles). If the bathroom must be shared with non-isolated personnel or if a designated bathroom traverses common areas, the PUI should be escorted by personnel wearing PPE while themselves wearing a mask. The escort will instruct anyone inside the bathroom to vacate prior to use. All surfaces used by the PUI must be cleaned with dilute bleach solution.

- Trash: Small trash receptacle with bag inside isolation berthing. Large receptacle double bagged will be placed immediately outside the isolation berthing. Biohazard sign will be placed on top. Only medical personnel or designated non-essential/non-high risk personnel will dispose of this trash to minimize risk to others. PUI will be instructed to tie off small bags and place in a large container daily. Consider the local population access to trash and dispose following approved policy for biohazardous waste.

- Maintain communication with personnel in isolation. The attending COVID provider will determine the need for more frequent assessments.

- Once a patient meets MedCon2 criteria or higher, continuous monitoring is recommended as their risk of rapid decompensation rises significantly. (MedCon2: Progressive symptoms that are concerning based upon provider clinical judgment. See Appendix A.)

- The Prolonged Field Care flowsheet provides a framework for recording frequent assessments and interventions. (See JTS Documentation in Prolonged Field Care CPG.)

- Consider using video chat (e.g., WhatsApp) to obtain vital signs and perform visual assessment of patient to minimize exposure in MedCon1. (MedCon1: Mild flu-like symptoms, SpO2>94% on room air, hemodynamically normal. See Appendix A.) Patients can take their own pulse oximetry reading and temperature at pre-determined intervals or cohort patients in isolation billeting can do it for each other.

- If concerning symptoms develop, the COVID attending provider performs an in-person exam using the best available PPE.

- 1) Notification of both medical and operational leadership is imperative and should occur soon after identification of a PUI.

- 2) Official notification in an approved format should be drafted and submitted to the command surgeon (or appropriate designee).

- 3) If MedCon2 or higher risk category, begin coordination for evacuation to a higher echelon of care as soon as possible.

- 4) Identify potential close contacts of PUI, screen for symptoms, and manage according to CDC guidelines for high risk exposure.

Population of Interest

All hospitalized patients who are COVID-19 positive (includes confirmed and presumptive cases when testing is not available).

Intent (Expected Outcomes)

- 1) Initial presenting symptoms are documented in the population of interest.

- 2) Co-morbidities are documented in the population of interest.

- 3) COVID test sample collection and result times are documented in the population of interest.

- 4) When intubation is required, staff document levels of use (level 1-surgical mask, level 2-N95, level 3- Powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR)).

- 5) Recommended treatments for severe and critical COVID-19 patients are received early after hospital admission.

Performance/Adherence Metrics

- 1) Number and percentage of patients with initial presenting symptoms are documented in the history and physical (H&P) record.

- 2) Number and percentage of patients with a complete past medical history (PMH) are documented in the H&P.

- 3) Number and percentage of patients with smoking history are documented in the H&P.

- 4) Documented number and percentage of patients with COVID test sample collection and result times.

- 5) Number and percentage of patients requiring intubation procedures who have documentation of level of PPE used by staff (level 1-surgical mask, level 2-N95, level 3-PAPR).

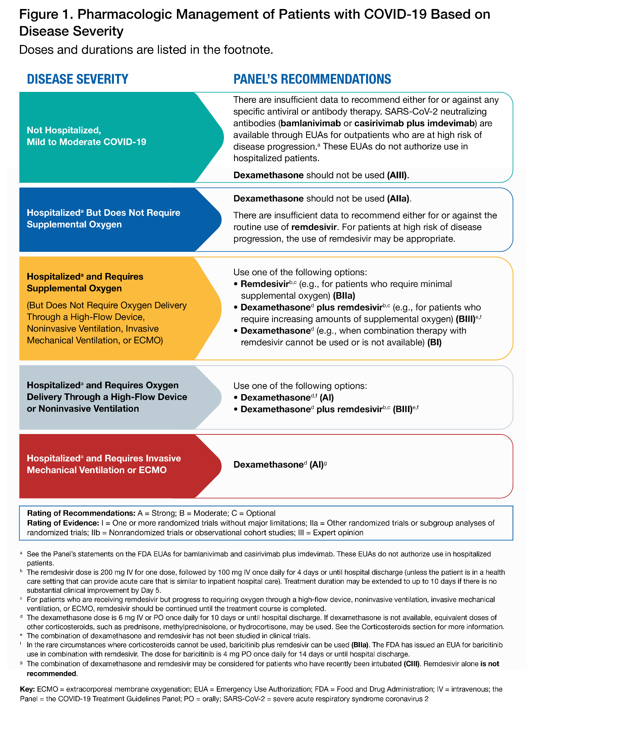

- 6) Number and percentage of severe and critical patients receiving remdesivir in < 24 hrs and < 48 hrs.

- 7) Number and percentage of severe and critical patients receiving dexamethasone in < 24 hrs and < 48 hrs.

- 8) Number and percentage of severe and critical patients receiving COVID convalescent plasma (CCP) in < 24 hrs and < 48 hrs.

Data Source

- Patient Record

- DoDTR

System Reporting & Frequency

- The previous sections constitute the minimum criteria for PI monitoring of this CPG. System reporting will be performed annually; additional PI monitoring and system reporting may be performed as needed.

- The JTS Chief, JTS Program Manager, and the JTS PI Branch will perform the system review and data analysis.

Responsibilities

It is the trauma team leader’s responsibility to ensure familiarity, appropriate compliance, and PI monitoring at the local level with this CPG.

(See Appendix F)

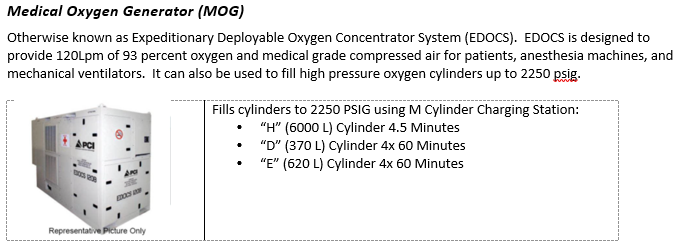

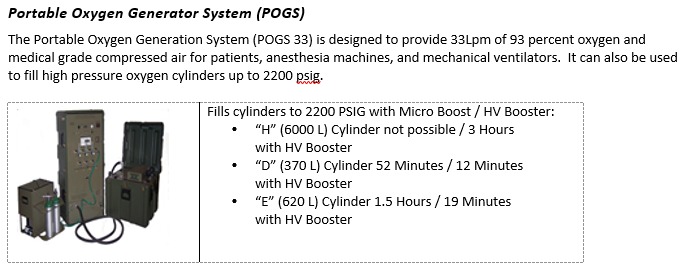

- 1) Take inventory of the equipment and supplies available at your treatment facility. Important items include small oxygen concentrators (SAROSTM), oxygen cylinders (D-cylinders and H-cylinders), and oxygen generating systems (POGS and EDOCS).

- 2) Identify the closest resource capable of filling oxygen cylinders. This may be a military biomedical maintenance team or host nation industrial gas supply company.

- 3) If you locate empty oxygen cylinders, begin the process of filling them right away. You will likely consume them quickly if you get a very seriously ill COVID-19 patient.

- 4) Develop a resupply plan for your oxygen cylinders. A very seriously ill COVID-19 patient will rapidly deplete oxygen supplies.

- If your facility has the capability to fill oxygen cylinders, then develop a plan to refill tanks. Identify someone not directly involved in patient care since tank refill and patient care may need to occur simultaneously.

- If your facility does not have the capability to refill oxygen cylinders, then develop a re-supply plan. One option is to coordinate medical cylinder exchange in conjunction with MEDEVAC missions.

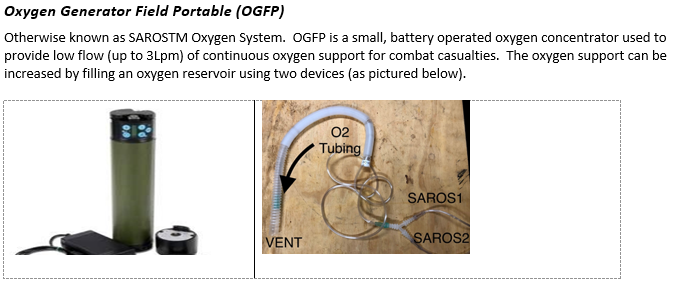

- 5) The SAROSTM oxygen concentrator can provide up to 3 Lpm of 100% O2. However, when unplugged, battery will only last 30 minutes on continuous flow.

- 6) SAROSTM can be daisy-chained together to provide higher flow, approximating 5-6 Lpm. A suction Y-connector can be used to connect several together.

- 7) Ventilators waste less oxygen when using a high pressure hose. A full D-cylinder providing 15 Lpm of O2 via disposable oxygen tubing will last 20-30 minutes. The same D-cylinder providing 100% FiO2 through a ventilator connected via green high pressure hosing will last 30-45 minutes (depending on minute ventilation).

- 8) Reducing minute ventilation (e.g., sedation with or without paralysis) and oxygen consumption (reduce FiO2 to absolute minimum to attain SpO2 88-92%) will extend oxygen supplies.

- 9) If transporting patient(s) to an evacuation pick-up site, anticipate delay and bring double the estimated oxygen supply.

(See Appendix G, Appendix H and Appendix I)

- 1) Minimum requirement for an effective ventilator in severe hypoxic respiratory failure:

- Must be able to provide Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP).

- Must allow for titration of tidal volume and respiratory rate (control minute ventilation).

- Must be able to provide supplemental oxygen greater than room air (>21% FiO2).

- 2) Commercial full function ventilators (e.g., Drager, Puritan-Bennett) may be available at some austere locations and are the ideal ventilators to use if available. These ventilators can perform advanced ventilation strategies and are indicated for treatment of COVID patients. Note: They are not transport ventilators, as the instruments are sensitive and should remain in an area where they can be protected. Transfer the patient to a transport vent for evacuation.

- 3) The Zoll (Impact) EMV+ 731 transport ventilator is available in many military equipment sets and certified to function in all aviation environments. IMPACT 754 ventilators are sufficient, but do not provide Pressure Control - Inverse Ratio Ventilation capability (discussed below).

- 4) Hamilton T1 transport ventilators provide specialized support options, including advanced pressure control options and integrated high flow oxygen therapy. Certified for ground transport and rotary-wing transport, but not approved for fixed wing aircraft (pressurized cabin) transport.

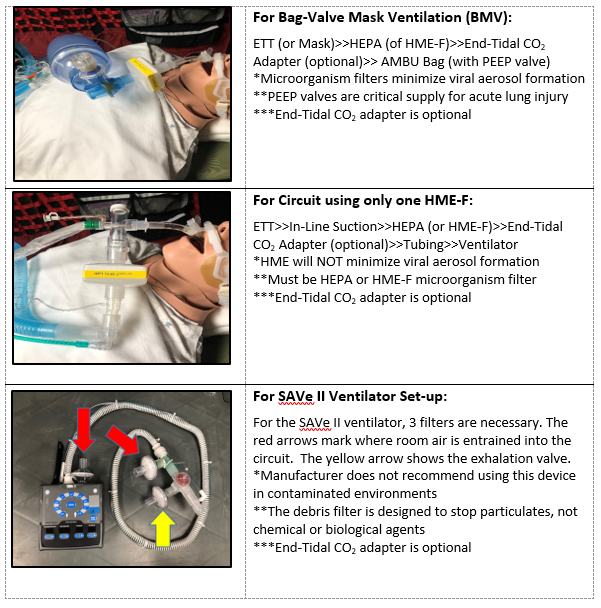

- 5) SAVe II rescue ventilators are an option with limited capability: PEEP only up to 10 cm H2O and minute ventilation only up to 8 Lpm. Oxygen reservoir tubing for the air intake is required to provide supplemental oxygen. If this is the only device available at your location, arrange transfer to a location with more advanced ventilator as soon as possible.

- 6) SAVe I rescue ventilator has no adjustability and cannot provide PEEP. DO NOT manage critically ill COVID-19 patients with this device. Manual ventilation with a Bag-Valve-Mask (BVM), PEEP valve, and supplemental oxygen will be more effective.

- 1) Minimize the number of personnel required to care for the PUI. Establish a priority list of who will be available to assist. Ensure that the rest of the team can maintain the combat casualty care capability.

- 2) In cases where evacuation may be delayed, establish work-rest cycles, allowing for adequate time to hydrate, eat, and sleep. This has been shown to reduce PPE waste, minimize provider exhaustion, and prevent accidental exposures.

- 3) Ambulatory PUIs (“walking wounded”) can potentially assist in monitoring and providing care to more seriously ill patients.

- 4) Consider having someone (not directly involved in patient care) act as a runner.

The equipment and supplies needed for the management of a critical ill COVID-19 patient are summarized in Appendix L and Appendix M.

Initial reports suggest that among COVID-19 patients who develop critical illness, the rapid decline typically starts about 5-7 days following the first symptoms. Closely monitoring these patients during this time period is critical for early intervention.

- 1) Minimize viral aerosol formation and direct exposure of medical personnel.

- 2) Use the best available PPE for high risk procedures like endotracheal intubation. (See Appendix B.)

- 3) Gauge the need for inserting an advanced airway on the patient work of breathing. COVID-19 patients decompensate rapidly – a low threshold for intubation allows more time for preparation and may prevent complications.

- 4) If the COVID attending provider does not feel comfortable with placing an advanced airway, consider teleconsultation and/or waiting for arrival of more experienced personnel (e.g., evacuation team). Never try to place an advanced airway unless you know how to do it.

- 5) One assistant is sufficient during intubation in most cases; however, an additional assistant can be standing by in the “warm” zone at least 2 meters away wearing appropriate PPE.

- 6) Passively pre-oxygenate with 100% O2 for at least 5 minutes. Consider placing a surgical mask on the patient (over top of nasal cannula or non-rebreather mask).

- 7) Utilize strict rapid sequence intubation technique – avoid BVM ventilation if possible. If available, place viral filter in-line during use of BVM.

- 8) Utilize video laryngoscopy (i.e. GlideScope) if available for intubation to limit direct exposure. If unable to intubate or obtain adequate vocal cord visualization on the first pass, consider the placement of a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) with viral filter. Ventilate with the BVM and PEEP valve until oxygenation is adequate. Then, re-attempt the procedure.

- 9) Chest X-Ray may not be available or feasible to confirm tube placement. Utilize end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) monitoring and auscultation to confirm placement.

- 10) General guide for tube size and depth is as follows: for males use 8.0 endotracheal tube (ETT) inserted to 25cm at the incisors; for females use 7.0 ETT inserted to 23cm at the incisors. In general, place as large an ETT as possible since secretions may be an issue.

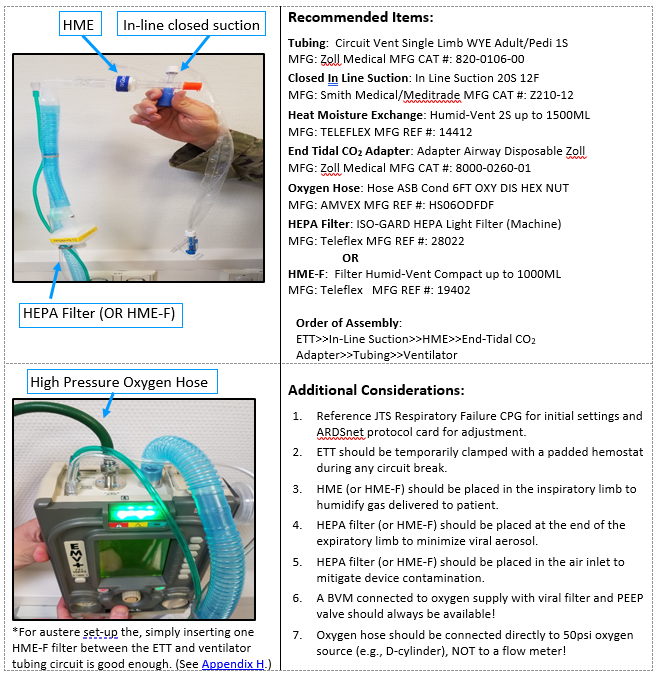

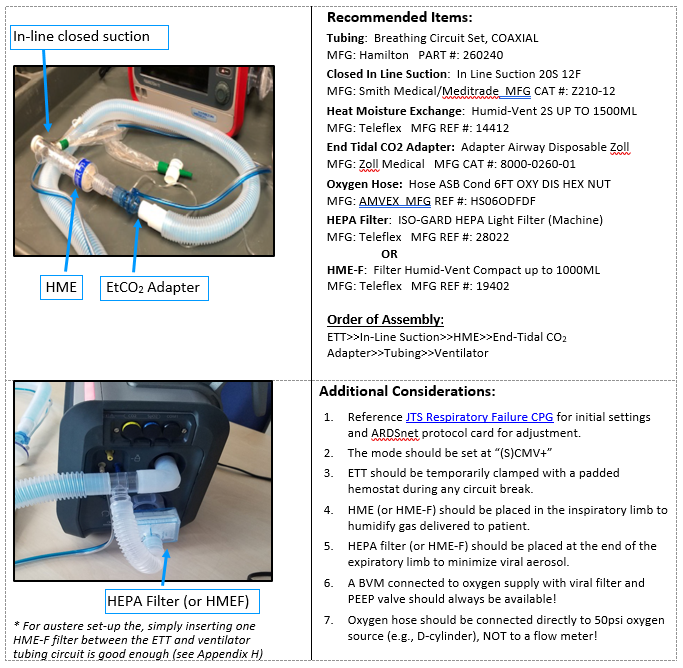

- 11) If available, place heated humidification device (e.g., Hamilton H900) or heat and moisture exchanger (HME) in the INHALATION circuit of the ventilator tubing. If available, place a HEPA filter (microbiological filter) or HME-F (HME plus microbiological filter) in the EXAHALTION circuit of ventilator tubing.

Cricothyroidotomy for definitive airway management:

- 1) Many medics and other providers operating independently in far-forward environments are trained to use cricothyroidotomy as their primary definitive airway. While the use of a surgical airway first line is appropriate in patients presenting in-extremis or with the loss of an airway (e.g., severely injured trauma patients with facial or neck trauma), patients with COVID-19 generally present with gradually progressive symptoms and intact native airways.

- 2) Early intra-theater transfer to a facility with advanced capabilities is preferable to early cricothyroidotomy whenever possible.

- 3) Laryngeal mask airway or other supraglottic airway placement may be a sufficient bridge to definitive airway placement. Placement of a mask over the LMA (hole cut in the middle of the mask for the LMA) will minimize aerosol spread from any air leak. PEEP above 10 cm H2O via LMA may not be effective and may exacerbate any leak around the LMA. Sedation and analgesic requirements for an LMA may be slightly more than with a cricothyroidotomy.

- 4) Cricothyroidotomy without the ability to provide mechanical ventilation consumes significant resources (manpower required to bag-ventilate the patient with PEEP, inefficient delivery of oxygen via bag-ventilation, and significant aerosol risk to those providing care).

Systemic Corticosteroids

Professional societies recommend using systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of severe and critical COVID-19 (see the DoD COVID-19 PMG for more details). If unfamiliar with corticosteroid treatment regimens, discuss with advanced provider via telehealth prior to initiating therapy.

Antimicrobial Therapy (to treat possible bacterial pneumonia co-infection)

- 1) Consider early use of azithromycin (500mg PO or IV daily for a minimum of 5 days) to treat mild to moderate community acquired pneumonia (CAP) in patients with lower respiratory tract symptoms and fever.

- 2) If azithromycin is not available, doxycycline (100mg PO or IV q12h) can be substituted for empiric treatment of bacterial pneumonia.

- 3) For patients with severe symptoms, recommend adding ceftriaxone (IV 2gm q24h is the best option) or ampicillin-sulbactam (3gm IV q6hr is a good alternative) or ertapenem (1g IV or IM q24h if it is the only available option).

- 4) Levofloxacin (750mg PO or IV q24h) is another reasonable option for empiric treatment of severe community-acquired pneumonia.

Fever Management

Fever management with acetaminophen every 6 hours (1000mg IV or 975mg PO or PR) as needed for temperature over 38°C.

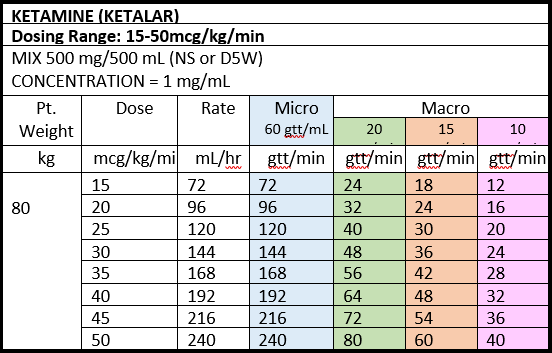

Sedation and Analgesia

- 1) Sedation goal is Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) -1 to -2 (comfortable, transiently responsive to verbal stimulation) and synchronous with the ventilator. Increase sedation and/or add narcotics to improve patient-ventilator synchrony. Use of paralytics may be required for very severe cases (as discussed below).

- 2) Ketamine may cause increased secretions which may require more frequent suctioning. If medication options are limited, consider more frequent dosing of midazolam to decrease the dose of ketamine required and potentially decrease the secretion burden.

- 3) A reference guide for starting and titrating a ketamine drip along with useful adjuncts is provided in JTS Analgesia and Sedation Management during Prolonged Field Care CPG.

- 4) Combined use of multiple sedatives (i.e. propofol, dexmedetomidine and/or midazolam) may act synergistically to decrease the total sedative dose and help to mitigate the hypotensive effects of propofol, however multiple continuous drips is not recommended outside of an ICU setting. A ketamine drip may be combined with bolus doses of additional medications.

- 5) Caution should be used with combining propofol and dexmedetomidine, especially in younger patients with higher vagal tone due to increased risk of bradycardia and hypotension.

- 6) Intermittent or doses of fentanyl or hydromorphone may be useful for analgesia and optimizing ventilator synchrony.

- 7) Low dose vasopressors may be necessary to support hemodynamics in the face of deeper sedation and higher PEEP. (See Appendix D.)

Bronchodilation

- 1) Use of metered-dose-inhalers (MDIs) over nebulized bronchodilators to treat wheezing will help to minimize risk for infectious aerosol.

- 2) If the ventilator tubing does not have a capped inlet for medication administration (aka MDI adapter) -- 1) clamp the ETT, 2) disconnect the ventilator, and 3) administer the MDI (6 puffs) directly into the INHALATION circuit. Then, reconnect the ventilator and unclamp ETT to insufflate the medication.

- 3) Magnesium Sulfate 2gm IV over 20 minutes (similar to treatment of an asthma exacerbation) may be a safer alternative for treatment of bronchospasm given the risks of disconnecting the circuit.

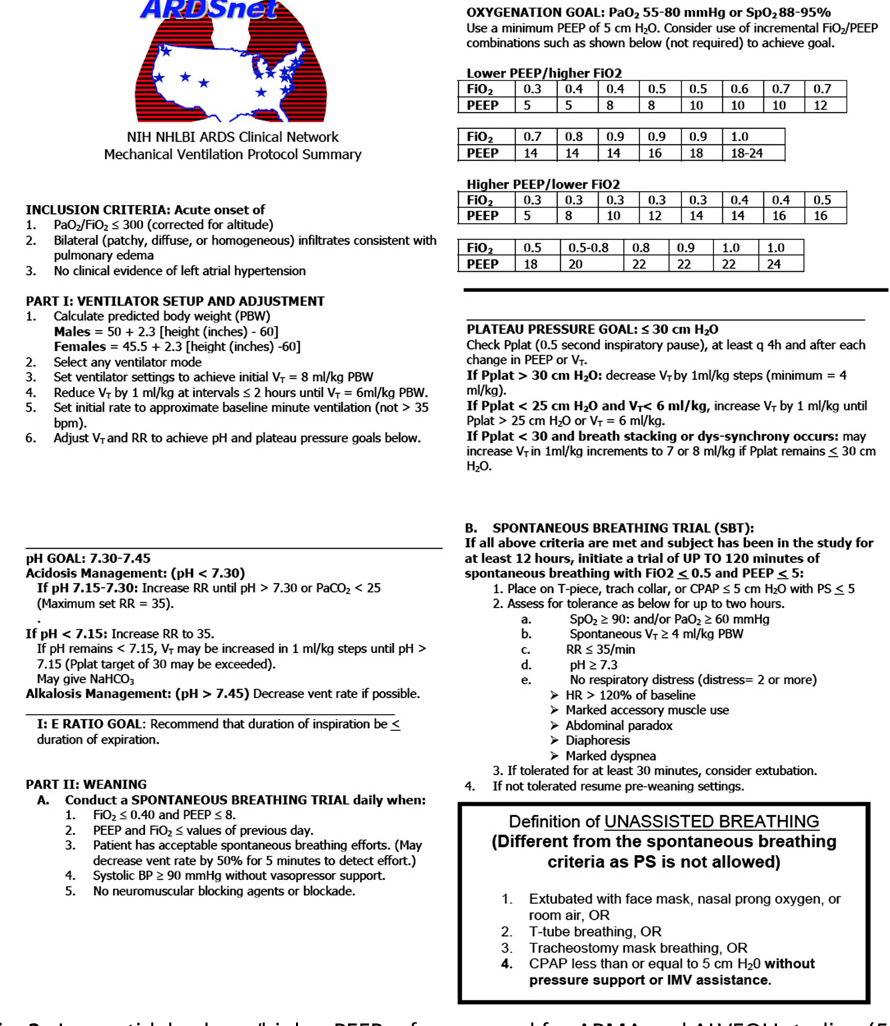

Lung-protective ventilation

- 1) Initiate lung-protective ventilation strategy.

- Tidal volume 6mL/kg ideal body weight (IBW)

- IBW – Men = 50 kg + (2.3 kg x (height in inches - 60))

- IBW – Women = 45.5 kg + (2.3 kg x (height in inches - 60))

- Maintain peak pressure less than 35 mm Hg

- Maintain SpO2 88-95% or PaO2 55-80 mm Hg

- Permit Hypercarbia (but keep arterial pH > 7.30)

- Use ARDSnet protocol. (See Appendix E)

- Tidal volume 6mL/kg ideal body weight (IBW)

- 2) If ETT must be disconnected from the ventilator for ANY reason, clamp the ETT to prevent decruitment and minimize viral aerosol formation.

- 3) If in-line suction devices are not available, de-recruitment will likely occur with suctioning. Salvage recruitment maneuvers may be necessary.

- 4) On the EMV+ 731 (mode AC-V) a recruitment maneuver can be done as follows:

- Change upper limit of Peak Inspiratory Pressure (PIP) alarm to 50 cm H20.

- Decrease tidal volume as low as possible (50mL).

- Increase PEEP to 30-40 cm H20.

- Hold for 40 seconds (if signs of hemodynamic instability develop, stop the recruitment maneuver, and resume prior settings).

- Increase PEEP to 2 cm H20 ABOVE prior PEEP setting.

- Increase tidal volume back to prior setting.

- Return upper limit of PIP alarm to prior setting.

- Monitor for any persistence of hemodynamic instability or persistently high PIP (Although rare, the high PIP encountered during RMs can cause pneumothorax).

- 5) Dry Lung. The mantra “a dry lung is a happy lung” still applies in severe COVID-19 care; over resuscitation is likely to be harmful. Fluid resuscitation should be guided by assessment of volume responsiveness. If available and evacuation is significantly delayed, loop diuretics can be used to attain a net even volume status, providing the patient is hemodynamically stable (i.e. not requiring vasopressor support).

Management of Oxygenation

- 1) Escalate PEEP to 12 cm H20 as aggressively as possible as hemodynamics allow to optimize oxygenation, minimize FiO2 needs, and extend oxygen supply.

- 2) Use the ARDSNet Protocol LOW PEEP table as a guide for further titration of PEEP. Refer to JTS Acute Respiratory Failure CPG.

- 3) Be prepared to start vasopressors and judicious use of IVF to support pre-load in the face of high PEEP (aka PEEP tamponade).

- 4) Consider a combination of paralysis and prone positioning early to lengthen duration of available oxygen supply.

- 5) Consider Inverse Ratio Ventilation (IRV) once patient reaches PEEP 18 cm H20 on the LOW PEEP table.

Management of Ventilation

- 1) If blood gas analysis is not available, a general EtCO2 goal of 35 mm Hg +/- 5, is adequate. However, if blood gas analysis is available (i.e. i-STAT), recommend obtaining a baseline PCO2 and correlate with EtCO2, especially since the gradient between the two is much wider in patients with significant lung disease (i.e. an EtCO2 of 40 may actually represent a PCO2 of 60 with a pH around 7.24).

- 2) The manual breath button on the bottom left of EMV+ 731 allows for manual measurement of plateau pressure (Pplat). The Pplat goal is less than 30 cm H2O with a secondary goal of maintaining driving pressure (Pplat minus PEEP) below 15 cm H2 In the absence of Pplat, a PIP target of less than 35 cm H20 is also reasonable.

- 3) If Pplat is greater than 30 cm H20, decrease set tidal volume by 1 mL/kg steps (about 50-80 mL). Titrate set respiratory rate (RR) up increments of 2 bpm to maintain pH and EtCO2 at goal. Avoid RR above 35 bpm given significant risk for breath stacking and auto PEEP (which will eventually make the patient hemodynamically unstable).

- 4) If i-STAT with blood gas cartridges are available, consider serial blood gas evaluation (adjusting frequency depending on patient stability).

Reverse Trendelenburg

Reverse Trendelenburg positioning (head of bed up, spine straight) can help offload abdominal pressure contributing to increased thoracic pressure. This can be extremely helpful maneuver to improve pulmonary compliance in obese patients and/or those with intra-abdominal hypertension.

Secretion Management Considerations

- 1) Increased secretions and mucous plugging of the bronchial tree are extremely common causes for increased oxygen requirement and difficulty with ventilation in patients with severe respiratory failure from lung infections.

- 2) Anecdotal evidence regarding COVID-19 patients suggests that secretions are problematic in some patients. Additionally, in-line suction (closed system) devices that minimize aerosol formation and de-recruitment are not usually available in austere settings.

- 3) Heated humidification prevents desiccation (drying out) of secretions and promotes ciliary clearance.

- Heated-humidification devices are designed to be used along with ventilators (e.g., Hamilton H900).

- Heat-Moisture Exchangers (HME) are supplies that fit in-line with the ventilator tubing and trap heat and moisture within the circuit.

- HME Filters (HME-F) are supplies that fit in-line with the ventilator tubing and provide HME and microbiologic filtration.

- 4) Pharmacologic treatment for secretions generally falls into one of three categories: mucolytics (break up mucous), bronchodilators, or anti-sialagogues (anti-salivation).

- Mucolytics:

- Pre-treat with for 10-15 minutes.

- 20% N-acetylcystine (Mucomyst) as 1-2mL direct instillation into ETT every 6 hours as needed for secretion control.

- 3% Saline (Hypertonic Saline) as 5mL direct instillation into the ETT every 6 hours as needed for secretion control.

- Bronchodilators: Albuterol will help dry up secretions. While ultimately decreasing secretion volume, bronchodilators may also increase the risk of a mucous plug formation. Use with caution.

- Anti-Sialagogues: Has the greatest effect on oral secretions with modest effect on pulmonary secretions (and therefore not routinely recommended for COVID-19 patients). However, antisialagogues such as scopolamine and glycopyrrolate are often effective at attenuating the increased secretions caused by high dose ketamine.

- Mucolytics:

- 5) Percussive chest physiotherapy is often provided by respiratory therapists in Role 3 facilities to facilitate secretion clearance. Manual (with hands) or mechanical (with percussive physical therapy devices) can be used to create the same effect.

Adjunctive Strategies for Severe ARDS

- 1) There is no single right answer as to which strategies should be used in severe ARDS. Each approach may or may not be feasible due to the resource constraints of the austere environment. If unfamiliar with these techniques, obtain teleconsultation.

- 2) Pressure Control – may include Inverse Ratio Ventilation (PC-IRV):

- EMV+ 731 with the most recent software package has the capability to do PC-IRV. While using AC-P mode, PC-IRV is achieved by increasing the Inspiratory-to-Expiratory (I:E) ratio above 1:2 (i.e. 1:1, 2:1, 3:1 and higher).

- PC-IRV cannot fully approximate Airway Pressure Release Ventilation (APRV), but is still the best available salvage mode using EMV+ 731.

- Once PEEP is maximized (or limited by peak inspiratory pressure) and oxygenation is still not yet at goal, increase the I:E ratio incrementally.

- Tidal volume goal remains the same as with conventional ventilation; adjust cycle time (60/RR) to optimize minute ventilation.

- Higher I:E ratios are not physiologic, so PC-IRV will likely require increased depth of sedation for patient comfort and synchrony.

- 3) Paralysis for Patient-Ventilator Synchronization

- Adequate depth of sedation is essential prior to starting a paralyzing medication; recommend RASS greater than -2.

- SCCM and DoD COVID-19 Practice Management Guide recommend intermittent paralytics over continuous infusions, if possible. Continuous infusion can result in prolonged paralysis if not closely monitored, especially if muscle twitch monitor is not available.

- Paralysis with Vecuronium:

- Bolus: 5mg to 10mg every 60-90 minutes as needed.

- Infusion: 0.8 to 1.2mcg/kg/min (approx. 80mcg/min for 80kg).

- Without pump: 40mg vecuronium in 250mL bag (50mL wasted) of normal saline yields 40mg/250mL = 160mcg/mL. For 80mcg/min = 0.5mL/min ~ 1gt every 12 seconds in 10gt tubing.

- Monitoring Goal:

- Absence of muscle movement and no evidence of spontaneous breathing on the ventilator. If possible, titrate to 2/4 TOF (testing device likely only available for surgical teams).

- Increased HR and BP may suggest inadequate sedation and should be empirically treated by increasing sedation.

- Once the patient is stabilized, consider holding the paralytic at least once every 24 hours to provide for assessment of sedation depth.

- DO NOT hold sedation until paralytic wears off unless absolutely necessary (e.g., sudden hypotension).

- 4) Prone Positioning

- “Awake Self-Proning” with high flow nasal cannula devices has been successfully used in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 lung disease. If patients are unable to tolerate prone positioning (i.e. strong desire to remain in a tripod position), DO NOT force them into the prone position.

- Reference DoD COVID-19 Practice Management Guide for full details on prone positioning precautions and procedures.

- Placement of either a central line or additional peripheral access is strongly encouraged PRIOR to prone positioning.

- Have push-dose vasopressor medication available during the process of prone positioning and un-positioning, as hypotension frequently occurs.

- Proning cycle is generally 16 hours of prone positioning each 24 hours. Match the proning cycle to the daily care plan as much as possible.

- Prone positioning may not be feasible or safe during evacuation.

Anticipate Complications

- 1) Pneumothorax can occur with higher PIP. Sudden increases in PIP and/or hemodynamic instability may indicate pneumothorax.

- 2) Pneumomediastinum with subcutaneous emphysema can also develop with the use of high PEEP (typically from dissection of air into the adventitia of small bronchi/bronchioles). The development of crepitus across the chest, neck, and/or upper extremities suggests the presence of this condition. Tension physiology from pneumomediastinum is EXCEEDINGLY rare and usually no intervention is needed.

- 3) Acute kidney injury leading to renal failure is a genuine threat to seriously ill COVID-19 patients. Patients unable to make urine can develop fatal arrhythmias from electrolyte abnormalities and acidotic blood. They need to be evacuated to a location capable of renal replacement therapy as soon as possible.

- Oliguria is defined as less than 0.5 mL/kg/hour of urine output (UOP).

- Oliguric patients should receive a bolus of 500 cc crystalloid. This may be repeated once if UOP does not improve. If the patient remains oliguric after a 1L bolus, consider the onset of acute tubular necrosis (ATN), especially if UOP remains low for more than 6 hours.

- As formal creatinine testing for acute kidney injury (AKI) is not likely to be available, consider urine dipstick testing with attention to specific gravity, proteinuria, and hematuria:

- An abnormally low (dilute) specific gravity in the setting of oliguria suggests tubular damage and the inability to concentrate urine.

- Significant proteinuria can be seen in ATN; however, this is not specific and can be seen in a variety of acute medical conditions.

- Hematuria may suggest the presence of myoglobinuria – consider rhabdomyolysis as a cause of acute kidney injury.

- If UOP suddenly declines or stops, flushing the Foley and/or performing a bladder ultrasound scan can help determine if the problem is mechanical (Foley blockage) or organic (true kidney injury).

- Once ATN sets in, do not aggressively fluid resuscitate or diurese simply to meet UOP goals. Use alternative markers of fluid responsiveness (like blood pressure response to passive straight leg raise) to help determine the need for further fluids and vasopressor medications.

- Monitor closely for the development of electrolyte disturbances, specifically metabolic acidosis and hyperkalemia. Use medical management of hyperkalemia as appropriate. The JTS CPG on Hyperkalemia and Dialysis in the Deployed Setting describes field-expedient techniques for peritoneal dialysis; however, this should be done in concert with teleconsultation.

- 1) An IV pump is recommended over dial-a-flow and drip-chamber titration (if available).

- 2) When outdoors, place the monitor, ventilator, and IV pumps upwind and as far away as possible from the patient to minimize contamination of caregivers.

- 3) Establish arterial line monitoring early when possible for patients with severe COVID-19 disease as they often become hemodynamically unstable.

- 4) If possible, establish central access early in anticipation of the need for continuous vasopressors. Multiple peripheral IVs may also be needed for infusions of sedatives, analgesia, antibiotics, etc.

- 5) A conventional central venous catheter can be placed through an introducer catheter (i.e. Cordis) to expand the number of available infusion ports. This should be done during the initial insertion under sterile technique, if possible.

- 6) Some severely ill COVID-19 patients may develop dilated cardio-myopathy with florid cardiogenic shock. This may be secondary to systemic inflammation, stress, or a direct viral myocarditis. Patients may also develop arrhythmias. Manage arrhythmias following Red Cross advanced life support guidelines.

- 7) An unexpected change in the vital sign trends or hypotension out of proportion to sedation and PEEP should merit evaluation for additional causes of shock. Limited transthoracic echocardiography may be useful in discriminating between hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and distributive shock (in personnel trained to perform the assessment).

- 8) Utilize dynamic parameters (i.e. skin temperature, capillary refilling time, pulse pressure variation, blood pressure response to passive straight leg raise, and/or serum lactate measurement) over static parameters to help guide the need for further fluid resuscitation (Surviving Sepsis Campaign COVID-19 Guidelines).

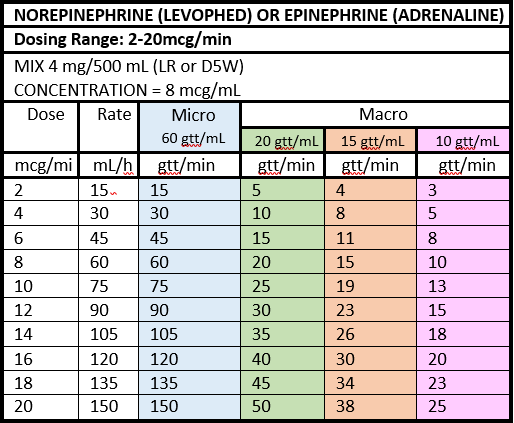

- 9) Norepinephrine is the first line vasopressor for most causes of shock. Fixed rate vasopressin infusion (0.04 units/min) is useful as an early adjunct in non-cardiogenic shock; start vasopressin when norepinephrine reaches doses above 12mcg/min. Epinephrine is sometimes the only option available in remote locations.

- 10) Vasopressors should be titrated to a MAP goal of 60- 65 mm Hg. (Surviving Sepsis Campaign COVID-19 Guidelines.)

- 1) Nasogastric or orogastric tube (NG/OGT) should be placed early for gastrointestinal decompression. If medical evacuation is significantly delayed (greater than 24-48 hours), consider starting enteral nutrition.

- 2) Enteral nutrition is contraindicated in hemodynamically unstable patients (i.e. those on high or increasing doses of vasopressors). Low volume tube feeding on patients with stable low doses of vasopressors is generally safe.

- 3) At a minimum, confirm position of gastric tube placement with auscultation over both lung fields and the abdomen along with aspiration of gastric contents. Urinalysis test strips for pH may provide an addition method for NG/OGT placement confirmation in patients not on acid suppressive therapy.

- 4) Goal 25-30 kcal/kg/day + 1-1.2 gm/kg protein; however, this might be difficult, especially in the absence of formal concentrated tube feeds.

- 5) Meal supplement drinks are not sufficient. For example, one Muscle Milk Light bottle contains only 150 kcal and 28 gm protein in 500 mL, which is extremely dilute compared to most tube feeding formulations. This potentially increase extra-vascular lung water (especially in the setting of critical illness) with minimal benefit to nutritional status.

- 6) A more concentrated alternative is to use commercially available protein powder (with similar caloric/protein content per scoop) at 1/4 the recommended concentration and mix in a blender until no clumps are visible. Administer in small volume boluses (e.g., 60mL via Toomey syringe) as tolerated every 2 to 4 hours to a goal of 1 gm/kg/day protein content.

- 7) Further recommendations for enteral nutrition can be found in JTS CPG for Nutritional Support Using Enteral and Parenteral Methods.

- 8) If possible, blood sugar checks should be obtained at least every 6 hours, particularly for those with known diabetes mellitus.

- 9) Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis should be given as long as there are no contraindications. Patients with COVID have demonstrated and increase risk of the formation of thrombus formation, therefore it is recommended to administer Lovenox 30 mg SQ twice daily (avoid if evidence of renal failure) or 7,500 units heparin SQ every 8 hours.

- 10) If pharmacologic prophylaxis is not available, manual ankle plantar/dorsi-flexion range of motion exercises and lower extremity massage every two hours. Consider applying compression stockings if available. DO NOT use ACE wraps.

- 11) Stress-Ulcer Prophylaxis should be given to all intubated patients as long as there are no contraindications. Famotidine 20 mg IV every 12 hours or 20 mg via NG/OGT twice daily, or consider and a proton pump inhibitor, if available (i.e. pantoprazole 40 mg IV daily or omeprazole via NG/OGT daily).

- 12) Ventilator Associated Pneumonia prevention bundle applied to the limitations of an austere environment includes:

- Head-of-bed elevation to 30 degrees

- Suction the oropharynx as needed

- Brush teeth every 12 hours, ideally with commercially prepared Chlorhexidine oral care if available.

- 13) The JTS CPG for Nursing Interventions in Prolonged Field Care provides in-depth discussion of the nursing tasks that may be required if medical evacuation is significantly delayed.

Cardiopulmonary arrest is a difficult topic. Generally speaking, in cases of cardiac arrest, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) in an austere environment may not be a wise use of resources unless the etiology for the arrest is rapidly reversible. Additionally, significant aerosol generation will invariably occur during CPR of a COVID-19 patient. It is reasonable during a pandemic to establish medical rules of engagement that discourage providers from performing CPR on infected patients. If CPR is performed, efforts should focus on reducing provider exposure to COVID-19 and prioritizing strategies with lower aerosol formation risk. (See DoD Covid-19 PMG.)

Each AOR should develop its own plan for categorizing COVID-19 patients (for the purposes of isolation and evacuation) based on guidance found in DoD policy.

Medical Evacuation using MedCon levels described in Appendix A is one example.

- 1) Patient movement should be anticipated for COVID-19 PUIs categorized as MedCon 2 or higher. There is no reason to delay notification request for evacuation.

- 2) Ground and Air Medical Transport will depend on local CASEVAC/MEDEVAC notification plan and CASEVAC/MEDEVAC platforms available for transport.

- 3) When clinically and operationally feasible and within the provider’s scope of practice, obtain central venous access in anticipation of need for multiple infusions, including vasopressors, during transport. Obtain at least two peripheral IV’s or one peripheral plus one central line access prior to transport, if possible.

- 4) Early placement of arterial line for invasive pressure monitoring is recommended, if available.

- 5) If there is evidence or suspicion for acute coronary syndrome or myocarditis, coordinate the medical management via teleconsultation prior to transport, if possible.

- 6) Patients requiring >3 Lpm oxygen support to maintain oxygen saturations >93% may not tolerate the hypoxic environment of aeromedical evacuation even with cabin altitude restrictions:

- Given concerns surrounding risk associated with procedures done emergently during transport, consider the need endotracheal intubation prior to transport.

- The most experienced provider should perform the procedure to secure the airway. Use a video laryngoscope (if available) and rapid sequence induction.

- Minimize people in the room during the procedure. Verify all staff have the best available PPE. (See Appendix B.)

- Consider consulting the Advanced Critical Care Evacuation Team (ACCET) DSN 312-429-BURN (2876) before transporting patients on moderate to high ventilator settings (PEEP > 14 and FiO2 > 70%). Refer to JTS CPG for Acute Respiratory Failure.

- If prone ventilation is to be utilized in-flight, it should be initiated on the ground with adequate time to document patient stability before transport.

- 7) If intubated, an NG/OGT should be placed pre-flight and attached to intermittent suction.

- 8) Pre-drawn and pre-mixed medications with primed tubing are examples of time saving measures to be optimized on the patient prior to transport.

- 9) Prepare patient records for handoff including medical notes, ECGs, laboratory results, and imaging results (if available).

- 10) Prepare patient belongings and ID/passport to accompany the patient.

- 11) Place PPE for flight on patient including eye protection and ear protection, and DO NOT forget face covering if not intubated.

- 1) Early patient reporting allows the evacuation team to prepare.

- The sending facility medical team should provide contact information (if possible).

- The evacuation team should contact the sending facility prior to mission (if possible).

- 2) Handoff to the transport team should include:

- Up-to-date COVID-19 testing status (PUI vs confirmed).

- Current vital signs, exam findings, and recent trends or changes.

- Current medication regimen if initiated (including antibiotics and anticoagulants).

- Critical care medication regimen (sedation, analgesia, paralysis, and vasopressors).

- Current PPE status, oxygen requirements and ventilator settings.

- Any potential COVID-19 related complications identified during management (e.g., heavy respiratory secretions).

- 3) Upon evacuation team arrival to receive the patient, handoff report should be repeated with key elements above, including any recent patient changes.

- 4) Transition to the evacuation team monitoring and support equipment will present risk of exposure to healthcare team. In an attempt to mitigate this risk, consider the following:

- Personnel should be limited to those directly involved in the care of the patient.

- Best available PPE should be worn by everyone involved in the care transition.

- ETT clamping technique should be instituted to limit aerosol creation during all ventilator circuit breaks including transfer to evacuation team ventilator.

- Sufficient time should be allotted to confirm adequate oxygenation and ventilation prior to departure of the evacuation team.

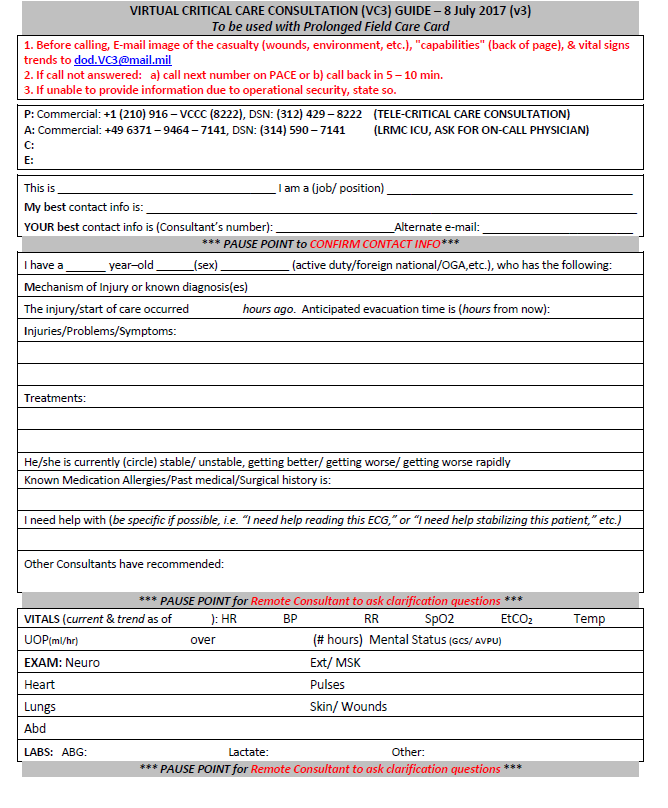

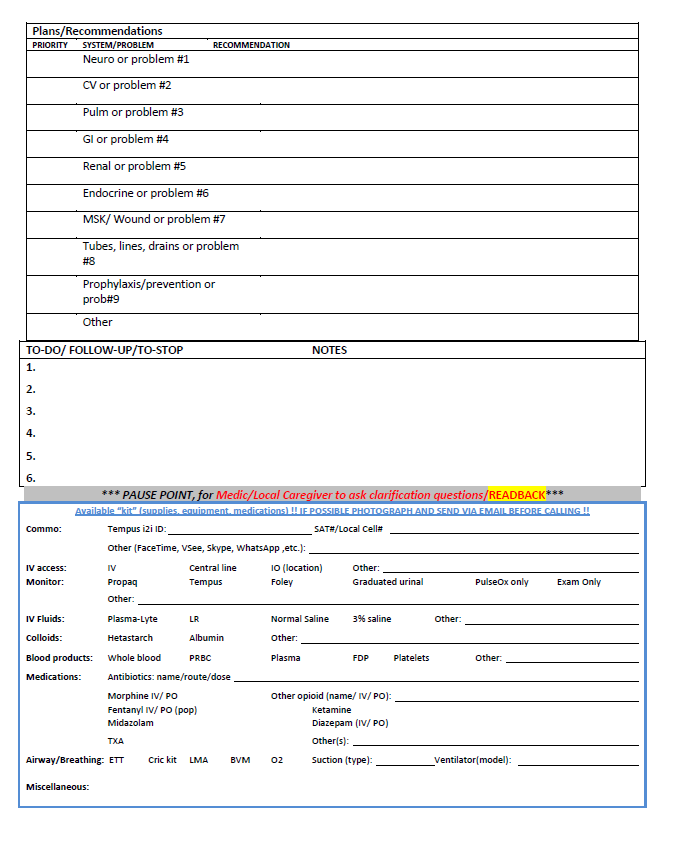

- 1) Regional Medical Operations Cell should prospectively publish local and regional PACE (Primary-Alternate-Contingency-Emergency) plans for both operational and clinical consultation. Forward-stationed medical teams should test these options PRIOR to needing urgent consultation.

- 2) Make use of telehealth resources such as the ADVISOR line (866-972-9966, or 833-238-7756), that includes the Virtual Critical Care Consultation (VC3) service. The ADVISOR program is specifically designed for operational virtual health support. Additionally, many VC3 consultants have deployed to remote locations and can help work through the unique problems faced in austere settings. Additional information on ADVISOR can be obtained by emailing advisor_office@mail.mil.

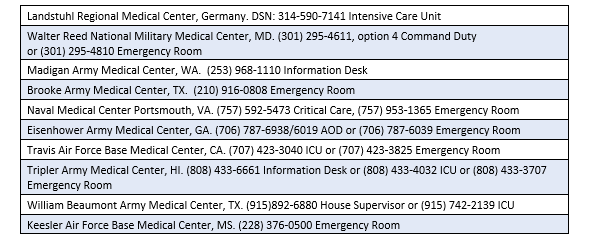

- 3) Alternatively, contact the following MEDCENs and ask for the on-call critical care staff:

- 4) Always be conscious of the need to maintain patient privacy and operational security.

- 5) Using a standard telemedicine script will improve communications and recommendations for patient management. (See Appendix K.)

READ FULL PDF

READ FULL PDF

READ FULL PDF