Crush Syndrome in Prolonged Field Care

Joint Trauma System

Introduction

This Role 1 prolonged field care (PFC) guideline is intended to be used after Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Guidelines when evacuation to higher level of care is not immediately possible. A provider of PFC must first and foremost be an expert in TCCC. This CPG is meant to provide medical professionals who encounter crush syndrome in austere environments with evidence-based guidance for how to manage the various aspects of crush injury care and monitoring. Recommendations follow a “minimum,” “better,” “best” format that provides alternate or improvised methods when optimal hospital options are unavailable.

Crush syndrome is a life and limb-threatening condition that can occur as a result of entrapment of the extremities accompanied by extensive damage of a large muscle mass. It can develop following as little as 1 hour of entrapment. Effective medical care is required to reduce the risk of kidney damage, cardiac arrhythmia, and death.

Crush syndrome is a reperfusion injury that leads to traumatic rhabdomyolysis. Reperfusion results in the release of muscle cell components, including myoglobin and potassium, that can be lethal. Myoglobin release results in rhabdomyolysis, with risk of kidney damage. Kidney damage leads to hyperkalemia and eventually cardiac arrhythmias. Calcium is taken up by injured muscle cells and this can cause hypocalcemia, contributing to cardiac arrhythmias. The risks are increased with large areas of tissue crushed (one or both lower extremities) and the length of time the casualty is pinned prior to extrication.

The primary treatment is aggressive fluid administration. Reperfusion after prolonged tourniquet application (>2 hours), extremity compartment syndrome, and severe limb trauma involving blunt trauma can also result in rhabdomyolysis by the same mechanisms as crush syndrome, and the treatment is the same.

For feedback or additional input on this CPG, please visit PFCare.org.

- Telemedicine: Management of crush syndrome is complex. Establish telemedicine consult as soon as possible.

Fluid Resuscitation

The principles of hypotensive resuscitation according to TCCC DO NOT apply in the setting of extremity crush injury requiring extrication.

However:

- In the setting of a crush injury associated with noncompressible hemorrhage, aggressive fluid resuscitation may result in increased hemorrhage. Balancing the risk of uncontrolled hemorrhage against the risk of cardiotoxic levels of potassium should ideally be guided by expert medical advice (in-person or telemedicine).

Fluids

Goal: Correct hypovolemia to prevent myoglobin injury to the kidneys and dilute toxic concentrations of potassium to reduce risk of kidney damage and lethal arrhythmias.

- Best: IV crystalloids Start intravenous (IV) or intraosseous (IO) administration IMMEDIATELY (before extrication). Rate and volume: initial bolus, 2L; initial rate: 1L/h, adjust to urine output (UOP) goal of >100–200mL/h (see below)

- Better: oral intake of electrolyte solution. Sufficient volume replacement may require “coached” drinking on a schedule.6

- Minimum: rectal infusion of electrolyte solution. Rectal infusion of up to 500mL/h can be supplemented with oral hydration.6,7

Life-threatening hyponatremia can result from large-volume administration of plain water. If using oral or rectal fluids because of unavailability of IV fluids or access, they must be in the form of a premixed or improvised electrolyte solution to reduce this risk.6

Examples of mixed or improvised electrolyte solutions include the following:

- World Health Organization (WHO) oral rehydration salts (ORS): preferred

- Pedialyte® (Abbott Laboratories, https://pedialyte.com)

- Per 1L water: 8 tsp sugar, 0.5 tsp salt, 0.5 tsp baking soda

- Per quart Gatorade® (Stokely-Van Camp Inc, www.gatorade.com): 0.25 tsp salt, 0.25 tsp baking soda

Monitoring

Goal: Maintain high UOP, detect cardiotoxicity, ensure adequate oxygenation and ventilation, avoid hypotension, trend response to resuscitation. Document blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), fluid input, urine output (UOP), mental status, pain, pulse oximetry, and temperature on a flowsheet.

Urine Output8,9

Goal: UOP of 100–200mL/h. The fluid rate should be adjusted to maintain this level of UOP.

- Best: place Foley catheter.

- Minimum: capture urine in premade or improvised graduated cylinder (e.g., Nalgene® bottle [Thermo Fisher Scientific, nalgene.com]).

- Maintain goal UOP until myoglobin can be monitored and normalized.

If UOP is below goal at IV fluid rate of 1L/h for >2 hours, kidneys may be damaged and unable to respond to fluid resuscitation. Consider:

- Teleconsultation, if available:

- Decreasing the fluid rate to reduce risks of volume overload (e.g., pulmonary edema)

- Hemorrhage or third spacing may cause hypovolemia. Consider: Increasing the fluid rate

Urine Myoglobin

Goal: Monitor for worsening condition

- Best: laboratory monitoring of urine myoglobin

- Better: urine dipstick monitoring of erythrocyte/hemoglobin (Ery/Hb)10 Urine dipstick Ery/Hb will be positive in patients with myoglobinuria.

- Minimum: monitor urine color. Darker urine (red, brown, or black), either consistently or worsening over time, is associated with increasing myoglobinuria and increased risk of kidney damage.

Hyperkalemia and Cardiac Arrhythmias

Release of potassium from tissue damage and kidney damage can result in hyperkalemia (>5.5mEq/L), resulting in life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias or heart failure14–17

Goal: Monitor for life-threatening hyperkalemia

- Best: laboratory monitoring of potassium levels, 12- lead electrocardiogram (ECG), cardiac monitor (e.g., ZOLL® [ZOLL Medical Corp, www.zoll.com]; Tempus Pro™ [Remote Diagnostic Technologies, http://www.rdtltd.com])

- Better: laboratory monitoring of potassium levels, cardiac monitor (e.g. ZOLL®, Tempus Pro™)

- Minimum: close monitoring of vital signs and circulatory examination

- Frequency: every 15 minutes for initial 1–2 hours

- Decrease frequency to every 30 minutes, then hourly if stable or if urine is clearing

- Monitor for premature ventricular contractions (PVCs; skipped beats), bradycardia, decreased peripheral pulse strength, hypotension

- Specific ECG signs: sinus bradycardia (primary sign); peaked T waves, lengthening PR interval (early signs), prolonged QRS interval, PVCs or runs of ventricular tachycardia, conduction block (bundle branch, fascicular)

- If PVCs become more frequent, the patient develops bradycardia, peripheral pulse strength decreases, or potassium levels are >5.5mEq/L or rising, treat urgently for hyperkalemia.

- Insulin and 50% dextrose (D50); calcium gluconate; albuterol (see treatment instructions below).

- Consider teleconsultation or more urgent evacuation to facility with laboratory and ECG monitoring, if possible.

- Use tourniquets to isolate limb(s) (see Tourniquets below)

Treatments for Cardiac Arrhythmias Due to Hyperkalemia

Treat if potassium level is >5.5mEq/L or there are cardiac arrhythmias (see above). Note that a normal ECG may occur in patients with hyperkalemia.

Goal: Restore normal ECG/prevent fatal cardiac complications

Treatment for Hyperkalemia

- Best: calcium gluconate; insulin + D50; albuterol; sodium polystyrene sulfonate

- Better: calcium gluconate; insulin + D50

- Minimum: any individual or combination of treatments, as available

- Calcium gluconate (calcium replacement): Increases serum calcium to overcome the effect of hyperkalemia on cardiac function.18 Alternate: may use calcium chloride, which is more irritating when administered via peripheral IV.

- Treatment instructions: Administer 10 mL (10%) calcium gluconate or calcium chloride IV over 2–3 minutes. Onset of effect: immediate. Duration of action: 30–60 minutes.

- Insulin and glucose: Insulin is given to lower the serum potassium level by driving it back into the cells; glucose is given to prevent hypoglycemia.18

- Treatment instructions: Give 10 units of regular insulin followed immediately by 50mL of D50. Onset of effect: 20 minutes. Duration of action: 4–6 hours.

- Albuterol: Lowers serum potassium level by driving it back into the cells; effect is additive with insulin.19

- Treatment instructions: Administer 12mL of albuterol sulfate inhalation solution, 0.083% (2.5mg/3mL) in nebulizer. Onset of effect: 30 minutes. Duration of action: 2 hours.

- Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate®; Concordia Pharmaceuticals, http://concordiarx.com): Lowers serum potassium level by removing potassium from the gut.18

- Treatment instructions: 15–30g suspended in 50–100mL liquid. Oral or rectal. Onset of action: >2 hours. Duration of action: 4–6 hours.

- Bicarbonate: Although routinely recommended as mainstay treatment to reduce kidney damage by raising the urine pH and diminishing intratubular pigment cast formation, and uric acid precipitation; to correct metabolic acidosis; and to reduce potassium levels, there is no clear evidence that bicarbonate reduces kidney damage,20 and the effect of reducing potassium is slow and unsustained.21

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate removes potassium from the body. All other treatments temporarily lower potassium by shifting it out of circulation and into the cells. Continue to monitor and repeat treatment when needed.

Tourniquets For Management of Crush

Tourniquets may delay the life-threatening complications of a reperfusion injury if immediate fluid resuscitation or monitoring is not initially available. Consider tourniquet placement for crush injury before extrication if the length of entrapment exceeds 2 hours and crush injury protocol cannot be initiated immediately.22–24

Goal: Delay acute toxicity until after fluid resuscitation and monitoring are available.

- Best: Apply two tourniquets side by side and proximal to the injury immediately before extrication

- Minimum: Apply two tourniquets side-by-side proximal to the injury immediately after extrication

- Initiate crush injury protocol before loosening tourniquet, and then only if the patient meets criteria for tourniquet conversion or removal given in the TCCC guideline

A limb that is cool, insensate, tensely swollen, and pulseless is likely dead. Patient may develop shock and kidney damage, and may die. Consider fasciotomy. If no improvement, place two tourniquets side by side and proximal to the injury and do not remove. Amputation anticipated.

Fasciotomy

Extremity compartment syndrome must be anticipated with crush injury and reperfusion injury.25–27

Goal: Decompress muscle, restore blood flow.

- Best: Perform fasciotomy (only if there are clinical signs of compartment syndrome). The earliest sign is limb swelling with severe pain with or without passive motion, persisting despite adequate analgesia, followed by paresthesia, pallor, paralysis, poikilothermia, and pulselessness.

- Only if qualified medical personnel or teleconsultation (ideally with real-time video capability) available.

- Then only if wound care available.

- Regional anesthesia with nerve block or IV sedation required.

- Minimum: Cool limb to reduce extremity edema (evaporative or environmental cooling only, do not pack limb in ice or snow because of risk of further tissue damage).

- Pain management: Refer to TCCC Guidelines for analgesia on the battlefield.28

Infection

For infection due to associated wounds and not crush injury itself, follow the Joint Theater Trauma System Infection Control Guidelines: “Prevent Infection in Combat-Related Injuries for Extremity Wounds.”29

Goal: Prevent infection.

- Best: Ertapenem, 1 gm IV/day (1g, 10 ml saline or sterile water)

- Better: Cefazolin, 2g IV every 6 to 8 hours; clindamycin (300–450 mg by mouth three times daily or 600 mg IV every 8 hours); or oxifloxacin (400 mg/day; IV or by mouth)

- Minimum: Ensure wounds are cleaned and dressed, and hygiene of wounds and patient optimized to the extent possible given environment.

Two appendices accompany this article: Appendix A presents a summary of fluid and equipment planning considerations; Appendix B summarizes monitoring and management considerations relative to time.

References

- Brochard L, Abroug F, Brenner M, et al. An official ATS/ERS/ESICM/SCCM/SRLF Statement: prevention and management of acute renal failure in the ICU patient: an international consensus conference in intensive care medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1128–1155.

- Greaves I, Porter K, Smith JE, et al. Consensus statement on the early management of crush injury and prevention of crush syndrome. J R Army Med Corps. 2003;149:255–259.

- Greaves I, Porter KM. Consensus statement on crush injury and crush syndrome. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2004;12:47–52.

- Gunal AI, Celiker H, Dogukan A, et al. Early and vigorous fluid resuscitation prevents acute renal failure in the crush victims of catastrophic earthquakes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1862–1867.

- Sever MS, Vanholder R. Management of crush victims in mass disasters: highlights from recently published recommendations. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:328–335.

- Michell MW, Oliveira HM, Kinsky MP, et al. Enteral resuscitation of burn shock using World Health Organization oral rehydration solution: a potential solution for mass casualty care. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:819–825.

- Foex BA, Dark P, Rees Davies R. Fluid replacement via the rectum for treatment of hypovolaemic shock in an animal model. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:3–4.

- Li W, Qian J, Liu X, et al. Management of severe crush injury in a front-line tent ICU after 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China: an experience with 32 cases. Crit Care. 2009;13:R178.

- Huang KC, Lee TS, Lin YM, et al. Clinical features and outcome of crush syndrome caused by the Chi-Chi earthquake. J Formo Med Assoc. 2002;101:249–256.

- Alavi-Moghaddam M, Safari S, Najafi I, et al. Accuracy of urine dipstick in the detection of patients at risk for crush-induced rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012;19:329–332.

- Better OS. The crush syndrome revisited (1940-1990). Nephron. 1990;55:97–103.

- Better OS, Abassi ZA. Early fluid resuscitation in patients with rhabdomyolysis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:416–422.

- Malinoski DJ, Slater MS, Mullins RJ. Crush injury and rhabdomyolysis. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20:171–192.

- Huerta-Alardin AL, Varon J, Marik PE. Bench-to-bedside review: rhabdomyolysis—an overview for clinicians. Cri Care. 2005;9:158–169.

- Nespoli A, Corso V, Mattarel D, et al. The management of shock and local injury in traumatic rhabdomyolysis. Minerva Anestesiol. 1999;65:256–262.

- Polderman KH. Acute renal failure and rhabdomyolysis. Int J Artif Organs. 2004;27:1030–1033.

- Zimmerman JL, Shen MC. Rhabdomyolysis. Chest. 2013;144: 1058–1065.

- Weisberg LS. Management of severe hyperkalemia. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3246–3251.

- McCullough PA, Beaver TM, Bennett-Guerrero E, et al. Acute and chronic cardiovascular effects of hyperkalemia: new insights into prevention and clinical management. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2014;15:11–23.

- Scharman EJ, Troutman WG. Prevention of kidney injury following rhabdomyolysis: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:90–105.

- Parham WA, Mehdirad AA, Biermann KM, et al. Hyperkalemia revisited. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33:40–47.

- Porter K, Greaves I. Crush injury and crush syndrome: a consensus statement. Emerg Nurse. 2003;11:26–30.

- Schwartz DS, Weisner Z, Badar J. Immediate lower extremity tourniquet application to delay onset of reperfusion injury after prolonged crush injury. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19: 544–547.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Crush injury and crush syndrome. http://www.acep.org/MobileArticle.aspx?id=46079&parentid=740

- Chen X, Zhong H, Fu P, et al. Infections in crush syndrome: a retrospective observational study after the Wenchuan earthquake. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:14–17.

- Guner SI, Oncu MR. Evaluation of crush syndrome patients with extremity injuries in the 2011 Van Earthquake in Turkey. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:243–249.

- Michaelson M, Taitelman U, Bursztein S. Management of crush syndrome. Resuscitation. 1984;12:141–146.

- Joint Trauma System, Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines. 2014. https://www.deployedmedicine.com/market/11/content/40 Accessed Mar 2018

- Joint Trauma System, Infection Prevention in Combat-related Injuries, 08 Aug 2016. https://jts.health.mil/index.cfm/PI_CPGs/cpgs

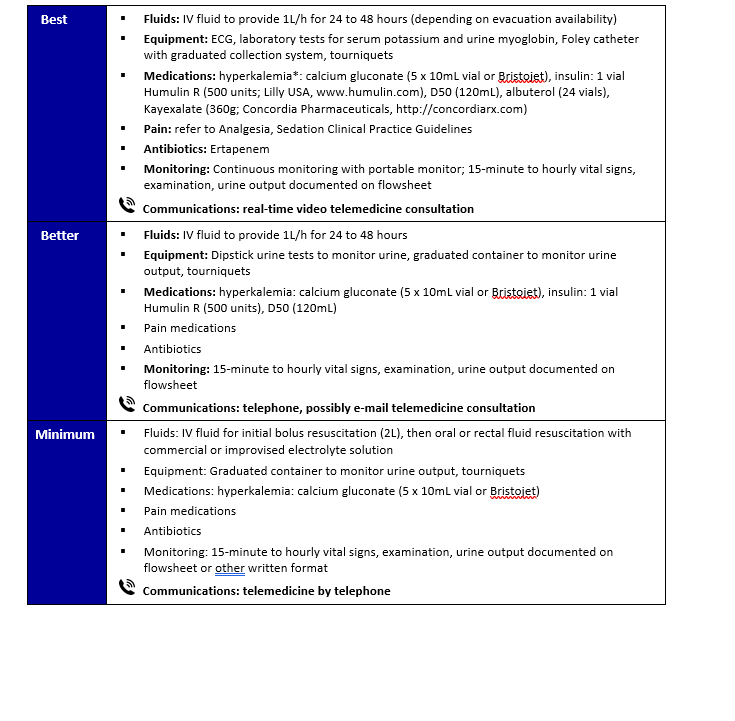

Appendix A: Fluid and Equipment Planning Considerations

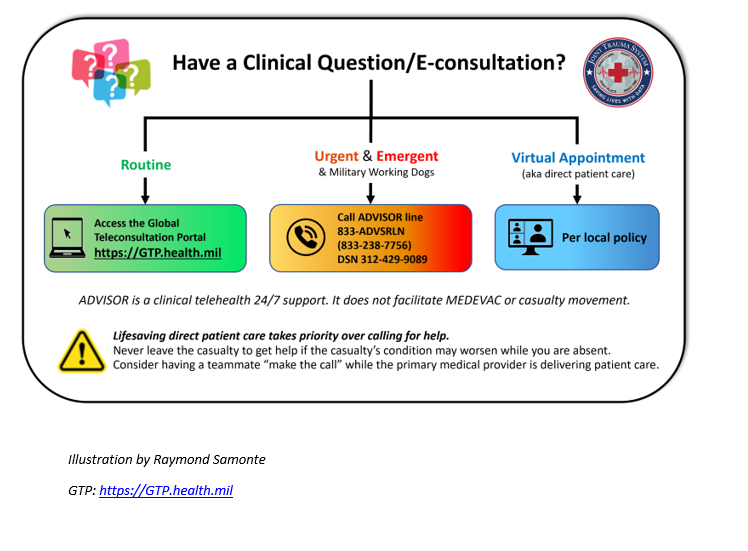

Appendix C: Teleconsultation/Telemedicine

Appendix D: Additional Information Regarding Off-Label Uses in CPGs

The purpose of this Appendix is to ensure an understanding of DoD policy and practice regarding inclusion in CPGs of “off-label” uses of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products. This applies to off-label uses with patients who are armed forces members.

Unapproved (i.e. “off-label”) uses of FDA-approved products are extremely common in American medicine and are usually not subject to any special regulations. However, under Federal law, in some circumstances, unapproved uses of approved drugs are subject to FDA regulations governing “investigational new drugs.” These circumstances include such uses as part of clinical trials, and in the military context, command required, unapproved uses. Some command requested unapproved uses may also be subject to special regulations.

Additional Information Regarding Off-Label Uses in CPGs

The inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is not a clinical trial, nor is it a command request or requirement. Further, it does not imply that the Military Health System requires that use by DoD health care practitioners or considers it to be the “standard of care.” Rather, the inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is to inform the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner by providing information regarding potential risks and benefits of treatment alternatives. The decision is for the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner within the practitioner-patient relationship.

Consistent with this purpose, CPG discussions of off-label uses specifically state that they are uses not approved by the FDA. Further, such discussions are balanced in the presentation of appropriate clinical study data, including any such data that suggest caution in the use of the product and specifically including any FDA-issued warnings.

With respect to such off-label uses, DoD procedure is to maintain a regular system of quality assurance monitoring of outcomes and known potential adverse events. For this reason, the importance of accurate clinical records is underscored.

Good clinical practice includes the provision of appropriate information to patients. Each CPG discussing an unusual off-label use will address the issue of information to patients. When practicable, consideration will be given to including in an appendix an appropriate information sheet for distribution to patients, whether before or after use of the product. Information to patients should address in plain language: a) that the use is not approved by the FDA; b) the reasons why a DoD health care practitioner would decide to use the product for this purpose; and c) the potential risks associated with such use.