Ocular Injuries and Vision-Threatening Conditions in Prolonged Field Care

Joint Trauma System

INTRODUCTION

Evaluation and treatment of ocular injuries and vision threatening conditions in a prolonged field care (PFC) situation can be extremely challenging. These events can lead to irreversible loss of vision with lasting effects on military service and overall quality of life. The goal of this clinical practice guideline (CPG) is to provide medical professionals with essential information on the recognition and treatment of ocular conditions when evacuation to an eye specialist is delayed. The guidelines are based on standard ophthalmic practice adapted to address the austere or remote environment, when the “Shield and Ship” guidelines are interrupted by delayed evacuation.

As with all medical concerns, recognition of the problem is the first step. This is a particular challenge for ocular conditions. Comprehensive ocular evaluation is not usually possible in austere locations and training in rapid recognition of ocular conditions may be limited. The ocular conditions covered in this guideline are the most common traumatic injuries and vision-threatening conditions that require rapid identification and treatment to prevent loss of vision. A more comprehensive review can be found in the Joint Trauma System CPG1 or Wilderness Medicine textbook.2

Telemedicine: Management of eye injuries is complex. Detailed physical examination information can only be communicated via pictures or video. Establish telemedicine consultation as soon as possible.

GOALS OF CARE

- MAINTAIN HIGH SUSPICION OF OCULAR INJURIES

The mechanism of injury will often suggest an ocular injury. Direct trauma with ocular laceration may be fairly obvious, but blunt trauma leading to an occult rupture on the posterior aspect of the globe or injury to the retina can be easily overlooked in a multitrauma patient. Small metallic fragments can penetrate the eye and leave it appearing deceptively intact. An awake and alert patient can report change in vision or eye pain; an unconscious patient cannot. Thermal burns to the face frequently cause eyelid burns and contraction, which increase the risk for exposure keratopathy. Critical details in the evaluation of ocular trauma include mechanism of injury and presence of properly worn ballistic eyewear at the time of injury.

2. ASSESS AND DOCUMENT VISUAL FUNCTION

Visual acuity is the vital sign of the eye. Whenever possible, visual acuity should be assessed and documented. Visual function immediately after trauma is an important prognostic indicator for visual outcome. Visual acuity can be effectively estimated with several field-expedient methods, starting with ability to read any printed letters such as labels on medical supplies. If the patient is unable to read letters, assess their ability to count fingers. If they cannot count fingers, evaluate for the ability to detect hand motions. If they cannot detect hand motion, evaluate light perception using a bright light. Document visual acuity along with other vital signs.

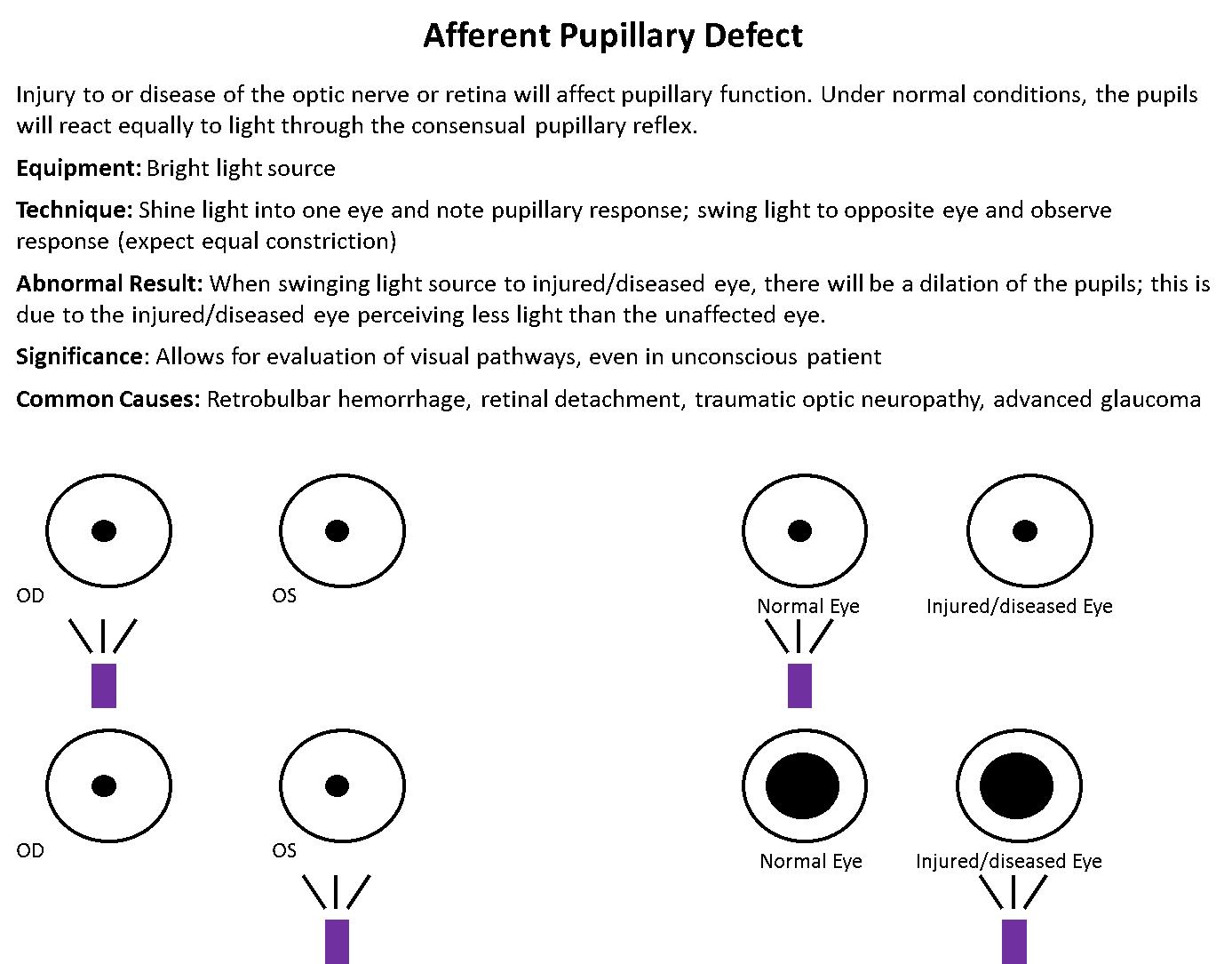

Assessing for a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD, also called the swinging flashlight test or Marcus Gunn Pupil; Appendix A) gives an indication of retina and optic nerve function. Shine a light in either eye; normally, both pupils should constrict equally. This reaction to light is equal unless there is damage to the optic nerve or the retina, in which case the pupil of the injured eye will dilate when the light is shone in the injured eye. Evaluating for an RAPD is essential in conditions such as retrobulbar hemorrhage (orbital compartment syndrome) or suspected retinal detachment. Notation of an RAPD is also an important prognostic factor for ophthalmic providers at later level of care.

3. EXAMINE FOR CRITICAL PHYSICAL FINDINGS

An obvious globe laceration or rupture with prolapsed intraocular contents can be a striking picture but may not be present in every severe eye injury. At times, the only findings of a significant eye injury may be penetrating periocular trauma or lid lacerations, a peaked or teardrop pupil, or abnormal anterior chamber depth.

Estimation of intraocular pressure (IOP) is essential in injuries such as retrobulbar hemorrhage, but is contraindicated in injuries with obvious or suspected open globe injury (OGI). If no OGI is suspected, IOP can be estimated using a two finger method. Using the index finger of each hand, gently apply alternating pressure on the globe through closed lids. There should be mild indentation of the eye with normal IOP (normal range, 10–21mmHg). With increased IOP, the globe will be much firmer when compared to the opposite eye, or the examiner’s own eye. The orbit around the eye may also feel tense in a retrobulbar hemorrhage.

A more detailed examination of the eye can be facilitated by the use of a direct ophthalmoscope for magnification. The examiner can use the plus lens dial (green or black numbers) to provide additional magnification. Details are found in Appendix B Use of the Direct Ophthalmoscope. Although deployed locations may have specific guidance against contact lens use, this may still be encountered. If a contact lens is clearly visible and accessible, it can be gently removed with forceps. Fluorescein will stain a contact lens, allowing for easy visualization.

4. MAINTAIN PATIENT COMFORT. PREVENT FURTHER DAMAGE.

Pain control is an important component of care in ocular injuries. Standard Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) pain control guidance applies to ocular injuries, including analgesic doses of ketamine if needed in systemic polytrauma. Additional guidance for pain control in PFC may be found in the CPG Analgesia and Sedation Management during Prolonged Field Care.3

Pain is not always present with serious eye injuries, and lack of pain should not be interpreted as lack of injury. Ocular injuries can cause a great deal of anxiety for patients, and this may affect care. A benzodiazepine may be added to the treatment plan for anxiety control and facilitation of care (diazepam 10 mg by mouth [PO] every 6 hours as needed).

A traumatized eye is highly susceptible to further damage; antiemetic medications are essential to prevent retching and increased pressure that can have significant effects on visual outcome.

Patching both eyes to decrease sympathetic eye movements has not been shown to improve visual outcome. Occluding both eyes will render the patient unable to move independently, may increase anxiety, and may put the patient and provider at increased risk in any PFC environment. The use of standard eye protection during patient transport can reduce the risk of further ocular injury or injury to the fellow eye. Eye protection can be used over a rigid shield to provide increased protection.

5. ESTABLISH CONTACT WITH EYE CARE CARE SPECIALIST. PRIORITIZE EVACUATION.

Determining the full extent of ophthalmic injuries and the resultant threat of permanent loss of vision is challenging without full ophthalmic training and equipment. All potential vision-threatening injuries should be evacuated with a goal of care by an eye surgeon within 24 hours. In some cases, with prompt teleconsultation or video consultation, it may be safe to delay evacuation to reduce the effect on the operational situation while providing necessary ophthalmic care. Evacuation within 24 hours is not possible in all situations; therefore, the goal of teleconsultation and forward care is to reduce morbidity and achieve the best possible outcome. In some operational environments, optometrists may be available to provide additional care or consultation closer to the point of injury.

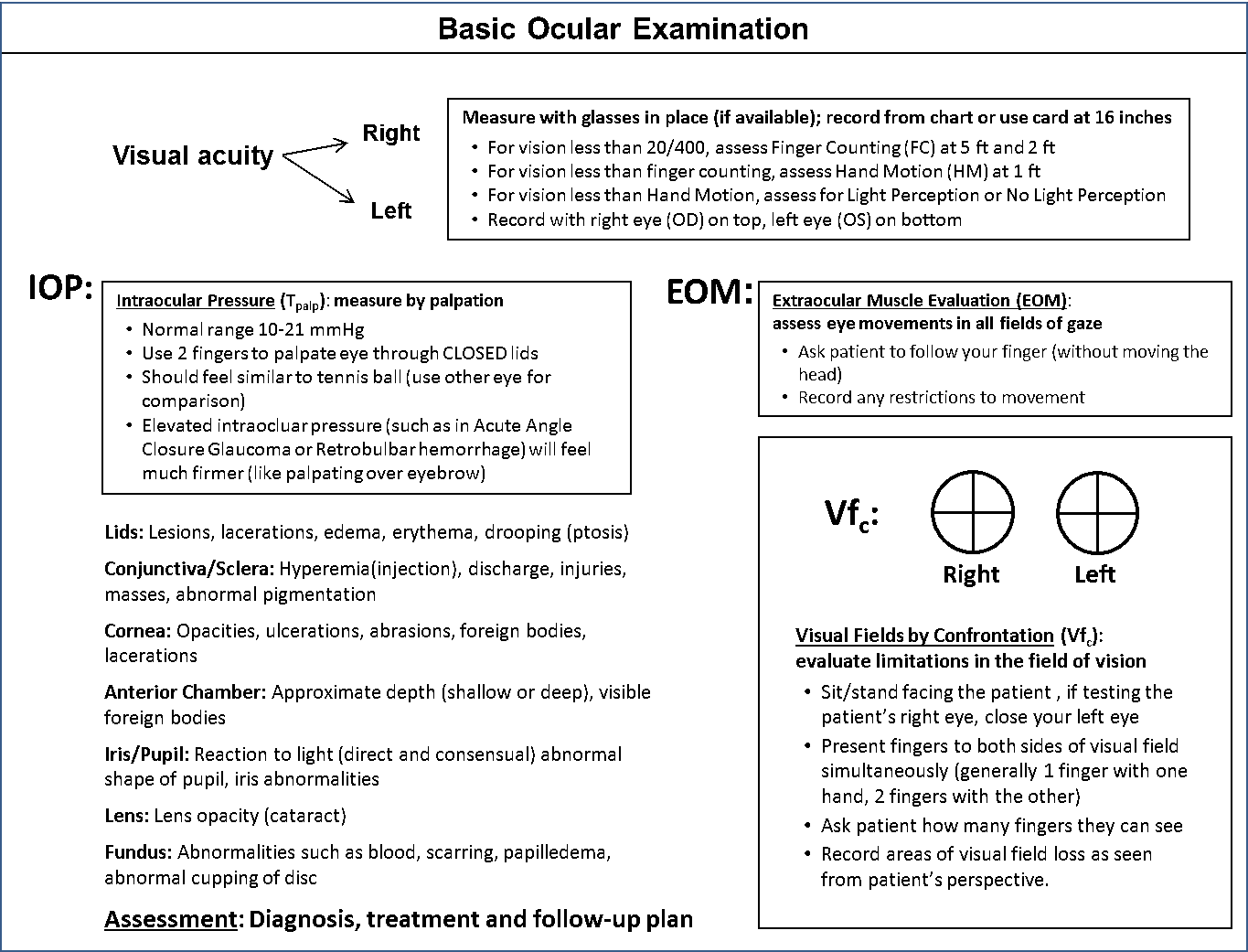

Ocular examinations have many specialized components that a specialist may request. An example template with explanation can be found in Appendix C Basic Ocular Examination.

SPECIFIC CONDITIONS

1. OPEN GLOBE INJURY

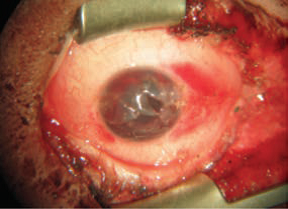

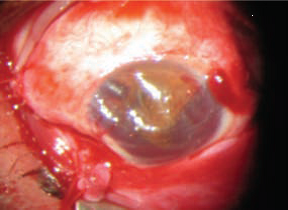

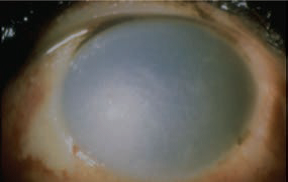

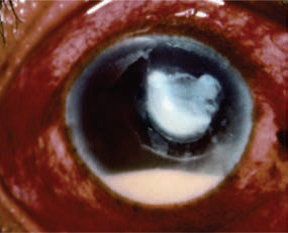

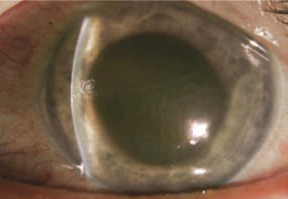

OGIs can result from penetrating/perforating trauma or from rupture of the globe due to massive compressive forces (Figures 1–5). Prompt surgical exploration and repair are crucial to restore or salvage vision and to prevent a devastating outcome. Safe and effective closure of an OGI is not yet feasible in a prehospital setting.

Goals

Prevent further damage to the eye, prevent infection in the eye (endophthalmitis), and evacuate to an eye surgeon as soon as possible.

Minimum

- Maintain high suspicion for OGI; treat any suspected open globe as an open globe until surgical exploration is available.

- Obtain and record visual acuity from the injured and noninjured eye.

- Apply a rigid eye shield without any type of gauze or bandaging under the shield to prevent further damage, per TCCC guidelines.4

- Initiate endophthalmitis prophylaxis with moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily; if intravenous (IV) administration is necessary, ertapenem 1g IV or intraosseously (IO) daily.5 Initiate pain control as needed.

- Initiate antiemetic (ondansetron 4mg oral dissolving tablet [ODT] IV/IO or intramuscularly [IM] every 8 hours as needed).

- Raise head 30°–45°.

- Activate evacuation with the goal of surgery within 24 hours.

- Initiate teleconsultation with photographs.

Better

- Minimize patient movements; maintain supine position with head at 30°–45°.

- Maintain endophthalmitis prophylaxis with an additional dose of moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily; if IV administration is necessary, ertapenem 1g IV/IO daily and the addition of clindamycin 300mg PO or IV every 8 hours if available; this is to cover Bacillus cereus, a particular concern in contaminated OGI.6

- Maintain antiemetic and pain control.

Best

- Perform a detailed ocular evaluation to include visual acuity and RAPD, and note any suspicious findings.

- Evaluation should be repeated with any reported change in vision or pain level by the patient. If symptoms are stable, perform ocular evaluation every 4 hours and before transfer.

Initiate real-time video telemedicine consultation.

- Coordinate surgical care within 8 hours of injury.

- No altitude restrictions are required for OGIs.

NOTES:

- Ultrasound is contraindicated for suspected OGI because it places pressure on the eye.

- Rigid eye shields are available in several different designs. Fit should be checked to ensure protection without any pressure on the eye. Standard eye protection may also be used to shield the injured eye.

Photographs by COL Mark Reynolds.

2. RETROBULBAR HEMORRHAGE / ORBITAL COMPARTMENT SYNDROME

Retrobulbar hemorrhage (RBH) is the most common cause of orbital compartment syndrome (OCS). It is a result of bleeding into the confined orbital space behind the eye, usually associated with blunt trauma (Figures 6 and 7). It is a vision-threatening condition causing increased pressure in the eye, leading to irreversible vision loss. Vision loss typically will occur after approximately 90 minutes of increased pressure.

Photographs by COL Mark Reynolds.

Other causes of OCS include orbital congestion secondary to burn resuscitation and significant orbital emphysema after orbital fracture (pneumo-orbita). OCS from any cause may have a delayed onset. Patients with trauma to the orbit must be closely monitored for development of OCS.

Goal

Lower the orbital compartment pressure as soon as possible to prevent tissue damage.

Minimum

- Prompt recognition of injury and identification of the need for intervention

- History of trauma with any of the following findings:

- Proptosis: bulging of the affected eye compared with the other eye; proptosis in RBH is often tense and painful

- Increased orbital pressure around the eye or IOP by palpation (increased firmness and resistance compared with opposite eye)

- Decrease in or loss of visual acuity

- Presence of an RAPD (Appendix A)

- Raise head 30°–45°.

- Initiate pain control as needed.

- Initiate antiemetic (ondansetron 4mg ODT/IV/IO/IM every 8 hours as needed).

- Perform lateral canthotomy/cantholysis (LCC) as soon as possible, within 90 minutes of injury if evacuation to a surgical capability is anticipated to take more than 60 minutes.

- Activate evacuation with goal of evaluation by an eye surgeon within 24 hours.

Initiate teleconsultation with photographs.

Better

- Minimize patient movements; maintain supine position with head at 30°–45°.

- Ice packs and avoidance of compressive dressings7

- Monitor for return of elevated orbital pressure.

Best

- Initiate a detailed ocular evaluation and continue monitoring IOP, vision, and RAPD.

- Continue to check for recurrence of elevated IOP even after LCC. If the vision deteriorates and the eye again becomes firm after LCC, this may signify rebleeding in the orbit. Evacuation of orbital hemorrhage is not feasible in a PFC environment and rebleeding will require medical treatment.8

- Acetazolamide: 500mg PO initial dose, followed by 250mg PO 4 times per day (Note: contraindicated in patients with sickle cell trait)

- If acetazolamide is not available or if the patient cannot take PO, either 3% hypertonic saline 250mL IV or mannitol: 1g/kg IV over 30–60 minutes can be used to decrease IOP.9

- Corticosteroid: 1g methylprednisolone IV once 10

- Initiate real-time video telemedicine consultation.

- No altitude restrictions are required for evacuation.

NOTES:

- LCC is a vision-saving procedure with minimal risk of causing additional ocular injury. When in doubt, perform the LCC immediately.

In thermal burns, consider early LCC (before full OCS develops). Fluid resuscitation requirements will take precedence over the use of medical treatments to reduce IOP.

3. BLUNT / CLOSED GLOBE INJURY

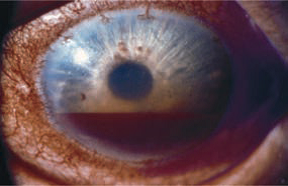

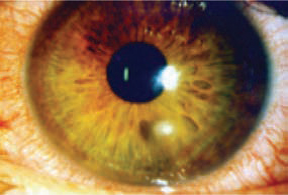

This category includes anterior segment injuries such as hyphema (bleeding into the anterior chamber) and posterior segment injuries such as vitreous hemorrhage and retinal detachment. Blunt trauma can result in severe loss of vision.

©2017 American Academy of Ophthalmology, reprinted with permission.

Hyphema can lead to increased IOP and corneal blood staining. This is graded on the amount of blood in the anterior chamber. The risk of IOP elevation increases with the grade of the hyphema (Figure 8).11

- Grade 0: no visible blood layering

- Grade 1: blood fills less than one-third of anterior chamber

- Grade 2: blood fills one-third to one-half of anterior chamber

- Grade 3: blood fills one-half to less than total anterior chamber

- Grade 4: blood fills entire anterior chamber

Goal

Identify significant ocular injuries; protect the eye from further injury.

Minimum

- Obtain and record visual acuity and critical injury details (e.g., mechanism of injury, presence of eye protection).

- Protect the injured globe and prevent further damage with a rigid shield.

- Raise the head 30°–45°; this allows any free-floating blood in the anterior chamber to settle away from the pupil and prevent pupillary block (which can lead to angle closure and elevated IOP).11

- Initiate pain control as needed; avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, because of risk of worsening intraocular bleeding.

- Prevent further injury with antiemetics (ondansetron 4mg ODT/IV/IO/IM every 8 hours as needed).

- Activate evacuation with goal of evaluation by an eye surgeon within 24 hours.

Initiate teleconsultation with photographs.

Best

- Initiate a detailed ocular evaluation to direct treatment.

- Hyphema (anterior chamber injury)11

- Topical corticosteroid drop (prednisolone acetate 1%) 4 times per day

- Cycloplegic eye drop (cyclopentolate 1%), 1 drop every 8 hours

- Monitor for rebleeding when the clot in anterior chamber retracts, usually at 3–5 days after injury.

- This may result in vision change and increased size of hyphema.12

- If there is evidence of further bleeding or increasing IOP, initiate medications to decrease IOP:

- Timolol 0.5%, 1 drop twice a day in affected eye

- Acetazolamide 500mg PO initial dose, followed by 250mg PO 4 times per day (Note: contraindicated in patients with sickle cell trait) or 3% hypertonic saline 250mL IV or mannitol: 1g/kg IV over 30–60 minutes.

NOTE: Tranexamic acid for prevention of rebleeding in hyphema has not shown any benefit 13 but may be used in multitrauma patients if otherwise indicated.

Posterior chamber injury: Injuries to the retina and optic nerve as a result of blunt injury will result in vision loss. Findings may include decreased visual acuity, vision loss, loss of red reflex through the pupil, positive RAPD, or evidence of vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment on ultrasound evaluation.

- Initiate supplemental oxygen as available if suspicious for retinal detachment (e.g., cut in visual field, decreased vision, positive RAPD); this may improve visual outcome.14

- If no evidence of OGI, perform careful ultrasound to evaluate vitreous and retina, if available/trained. Transmit ultrasound images with telemedicine consultation to an eye specialist.

Initiate real-time video telemedicine consultation.

- No altitude restrictions are required for blunt/closed globe injury.

4. EYELID LACERATION

Lid lacerations can result from either sharp or blunt trauma (Figures 9–11). As with other injuries, the primary concern with lid injuries is the possibility of underlying globe injury. Lid lacerations have a low incidence of infection (unless the causative factor is an animal or human bite). Any avulsed tissue should be preserved in saline and chilled, whenever possible, and sent with the patient—not discarded or debrided. Meticulous closure of eyelid structures with proper magnification is usually required to maintain lid function. If fat is visible in an eyelid laceration, this indicates violation of the orbital septum, a key anatomic barrier to infection. If prolapsed orbital fat is identified, appropriate antibiotic coverage is needed as well as expedited evacuation for surgical exploration and repair. Do not attempt to excise or suture exposed orbital tissue; this can lead to uncontrolled bleeding in the orbit.

Photographs by LTC Marcus Colyer (9) and COL Mark Reynolds (10, 11).

Goals

Prevent infection; protect the eye from further injury.

Minimum

- Maintain high suspicion for OGI; treat any suspected open globe as such until surgical capability is available.

- Obtain and document visual acuity from the injured and noninjured eyes.

- If there is any concern for OGI, protect the injured globe and prevent further damage with a rigid eye shield. Polyethylene film (food grade) may be used to cover the eyelid wound under the rigid shield to prevent drying of the injured tissue.

- Initiate pain control as needed.

- Activate evacuation with goal of evaluation by an eye surgeon within 24 hours.

Initiate teleconsultation with photographs.

Better

For foreign body penetration, animal bite, or laceration with visible orbital fat, start antibiotics: moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875mg/125mg PO every 12 hours or ertapenem 1g IV/IO daily.

Best

- Initiate a detailed ocular evaluation to include visual acuity, RAPD, and note any suspicious findings.

- Irrigate wound very gently with clean water (or sterile saline, if available).15

- Do not debride any tissue.

- Temporary closure with steristrips

- Tetanus prophylaxis

- Consider the need for rabies vaccination.15

Initiate real-time video telemedicine consultation.

- No altitude restrictions are required for evacuation.

5. ORBITAL FRACTURE

Fracture of the orbital bones occurs when an object that is larger than the width of the orbit (e.g., fist or softball) strikes the orbit. The acute expansion of orbital contents and mechanical buckling forces can result in fractures of the medial wall or orbital floor. This can cause herniation of orbital contents into the surrounding sinuses and entrapment of the extraocular muscles in the fracture site. Physical examination findings consistent with orbital fracture include a palpable and painful step-off along the orbital rim, enophthalmos (globe is further back in the orbit compared with the other eye), restricted eye movement, and numbness below the eye (caused by damage to the infraorbital nerve).16 Trismus and malocclusion may indicate a larger zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture. Orbital fractures are not ophthalmic emergencies but may require surgical treatment to prevent the complication of double vision from ocular misalignment.

Goals

Evaluate for concurrent open or closed globe injury and prevent long-term complications.

Minimum

- Maintain a high suspicion for associated OGI; treat as a suspected open globe until eye surgical evaluation is available.

- Obtain and record visual acuity from the injured and noninjured eyes.

- Instruct the patient not to blow nose. This may force air into the orbit through fracture site, leading to OCS from pneumo-obita, which would require LCC.

- Initiate pain control as needed.

- Raise head 30°–45°.

Initiate teleconsultation with photographs.

- Activate evacuation with goal of evaluation by an eye surgeon within 24 hours.

Better

- Initiate antibiotics if an orbital fracture suspected; this is to prevent sinus pathogens from spreading to the orbital tissues: moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875mg/125mg PO every 12 hours or ertapenem 1g IV/IO daily.

- Nasal decongestants such as oxymetazoline (e.g., Afrin; Bayer, http://www.bayer.us/) nasal spray twice a day for 3 days (limit use to 3 days to prevent rebound effect). Oral decongestants, such as pseudoephedrine 30mg every 6 hours, can be used if nasal spray is not available.

- Prevent further injury with antiemetics (ondansetron 4mg ODT/IV/IO/IM every 8 hours as needed).

Best

- Initiate a detailed ocular evaluation to include visual acuity, RAPD, and note any suspicious findings.

- Ice packs for 20 minutes every 1–2 hours for the first 48 hours to reduce swelling.

- Monitor for delayed development of OCS and perform LCC as needed.

Initiate real-time video telemedicine consultation.

NOTES:

- No altitude restrictions are required with orbital fractures, but patient should be monitored for increasing pain and/or decreasing vision from pneumo-orbita OCS requiring LCC.

- An important consideration in orbital floor fractures is the inferior rectus muscle becoming entrapped in the fracture (so-called trapdoor fracture). The resultant traction on the rectus muscle can trigger the oculocardiac reflex and result in intractable nausea and vomiting, symptomatic bradycardia, and possibly heart block. Although this is more common in pediatric patients (termed “white-eye” blow-out fractures), it is not exclusive to the pediatric population and has been reported in young healthy adults. Urgent surgical repair (within 72 hours) is recommended for an entrapped fracture with these symptoms.

6. CHEMICAL INJURIES

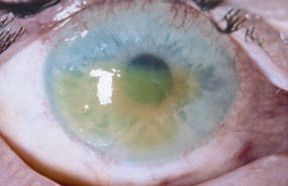

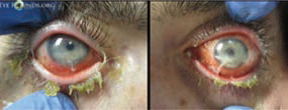

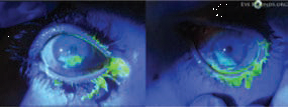

Acid (e.g., sulfuric, hydrochloric) and alkali (e.g., bleach, lime, ammonia) burns can cause significant injuries leading to permanent loss of vision and are considered ophthalmic emergencies. Alkali burns are more common and have more potential for damage than acid burns.16 Ongoing ocular care beyond the initial thorough irrigation will be required if evacuation is delayed. Chemical injuries are graded on a scale of I to IV.17 The modified Hughes classification (Table 1) can be used to grade the degree of limbal ischemia that correlates with prognosis. Regardless of the chemical causing the injury, immediate irrigation is the essential first step. Additional treatment will be based on grade of injury. Injuries are graded on the basis of the following examination findings (Figures 12–14):

Grade I

Cornea Epithelium - Less than one-third loss

Corneal Clarity - Iris details clearly visible

Limbal Ischemia - No ischemia

Grade II

Cornea Epithelium - More than one-third epithelial loss

Corneal Clarity - Iris details blurred but visible

Limbal Ischemia - Less than 25% ischemia

Grade III

Cornea Epithelium - Complete epithelial loss

Corneal Clarity - Pupil can be seen

Limbal Ischemia - 25%–50% ischemia

Grade IV

Cornea Epithelium - Complete epithelial loss

Corneal Clarity - Opaque cornea

Limbal Ischemia - More than 50%

- Corneal epithelial damage: How much epithelium has been lost?

- Clarity of cornea: Can the normal structures (iris, pupil) be seen through the cornea?

- Limbal ischemia: Does the conjunctiva at the edge of the cornea appear normal or are there areas that are blanched white?

Grade I injuries may have corneal epithelial damage but a clear cornea, no corneal opacity, and no limbal ischemia.

These injuries generally carry a good prognosis for recovery. Irrigation and topical care are frequently the only required interventions.

Grade II through IV injuries will have corneal haze or opacity and limbal ischemia.

These injuries will have a guarded prognosis and will require more intensive treatment. Grading is determined by the most severe finding. For example, an eye with a clear cornea but showing limbal ischemia would be classified as grade II or higher.

Goals

Initiate eye irrigation as quickly as possible to reduce damage to the eye, treat the injury to prevent or reduce scarring and visual loss.

Minimum

- Immediate thorough irrigation to remove the chemical agent is the essential first step (IV fluid, sterile water, or clean water).

- Continue irrigation, using at least 2L of fluid.

- Use tetracaine eye drops as needed to facilitate irrigation (unpreserved lidocaine 2% can be substituted as eye drops if tetracaine is not available).

- Irrigation may not flush all chemical agents from the eye; examine for particulate matter and remove using a cotton tip applicator (CTA).

- Initiate pain control as needed. DO NOT use topical anesthetics for pain control; they significantly impair corneal healing.

- Initiate teleconsultation with photographs (include full facial views).

Photographs by The University of Iowa and EyeRounds.org (12) and ©2017 American Academy of Ophthalmology, reprinted with permission. (13, 14).

Better

- Evaluate ocular pH using a urine test strip and CTA.

- Do not place the test strip directly on the eye. Roll a

- CTA across the conjunctival surface and then onto the test strip. If pH ≠ 7, continue irrigation and recheck until pH = 7.

Best:

- Initiate real-time video telemedicine consultation; treatment duration for more significant chemical burns will vary depending on the injury and are best determined by an eye-care specialist

- Further treatments and need for evacuation will be directed by the grade of injury. Evaluation will require fluorescein strips to evaluate the corneal epithelium and a light source, preferably with a red-free option (i.e., green lens), for evaluation of limbal ischemia.

Grade I:

- Topical antibiotic ointment (e.g., erythromycin ophthalmic ointment) 3 times per day Cycloplegic eye drop (cyclopentolate 1%), 1 drop every 8 hours, if available, for photophobia

- Preservative-free artificial tears 3 times per day, alternating between ointment treatments

Grades II–IV:

- Moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops, 1 drop every 8 hours

- Topical corticosteroid (e.g., tobramycin/dexamethasone or prednisolone acetate 1%) 1 drop every hour while awake

- Cycloplegic drop (cyclopentolate 1%), 1 drop every 8 hours, if available

- Doxycycline 100mg PO every 12 hours; this has anti-inflammatory and anticollagenase benefits for the ocular surface.

- The following have been shown to improve corneal healing with severe chemical burns; add to the treatment if available:

- Vitamin C 2g 4 times per day.17

- Supplemental oxygen (administer 100% for 1 hour twice daily).19 No data are available for the effectiveness of lower doses of oxygen.

- Reassess frequently until evacuation.

- No altitude restrictions for flight

7. PRESEPTAL AND ORBITAL CELLULITIS

Infection anterior to the orbital septum (usually involving the eyelid) is termed preseptal cellulitis. Preseptal cellulitis will present with tenderness, swelling, and erythema of the eyelids, with no orbital findings (e.g., no sign of proptosis, eye movement restriction, or change in vision). Preseptal cellulitis can generally be managed with oral antibiotics, but the possibility of methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) must be considered.

Infection in the orbit (posterior to the orbital septum) can occur as a result of adjacent sinusitis, skin infection, puncture wounds, or orbital foreign bodies. Multiple organisms, including staphylococcal, streptococcal, and gram-negative bacteria, are usually responsible. Orbital cellulitis has the potential to progress rapidly and may lead to irreversible loss of vision or intracranial extension. Orbital cellulitis presents with pain, proptosis, conjunctival injection, decreased vision, and loss of ocular mobility (which may cause double vision).

Goal

Recognize infection early and start oral antibiotics for preseptal cellulitis and IV antibiotics for orbital cellulitis. Evacuate to an eye surgeon as rapidly as possible if orbital cellulitis is suspected.

Preseptal cellulitis (Figure 15)

- Minimum

- Moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily.

- Does not cover MRSA; follow closely for worsening condition.

- Initiate pain control as needed.

- Activate evacuation with goal of evaluation by an eye surgeon within 24 hours.

- Initiate teleconsultation with photographs.

Best

Trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole DS 1 tablet PO every 8 hours combined with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875mg every 12 hours.

Orbital cellulitis (Figure 16)

Minimum

- Prompt recognition of the condition and the need for rapid intervention

- Initiate pain control as needed.

- Initiate IV access with broad-spectrum IV antibiotics: ertapenem 1g IV/IO daily or levofloxacin 500mg IV once a day.

- Initiate pain control as needed.

- Activate evacuation with goal of evaluation by an eye surgeon within 24 hours.

Initiate teleconsultation with photographs (include full facial views).

Better

Nasal decongestants such as oxymetazoline (e.g., Afrin) nasal spray twice a day for 3 days (limit use to 3 days to prevent rebound effect); this will aid in draining of contributing sinusitis. Oral decongestants, such as pseudoephedrine 30mg every 6 hours, can be used if nasal spray is not available.

Best

- Initiate a detailed ocular examination.

- Monitor vision every 4 hours until evacuation (may take 24–36 hours to show improvement).

Initiate real-time video telemedicine consultation.

- No altitude restrictions for flight

8. INFECTIOUS KERATITIS (CORNEAL ULCER)

Infections in the cornea can lead to corneal scarring and permanent effects on vision (Figures 17 and 18). The most common risk factor for corneal ulcer is contact lens use.

Goal

Early recognition and treatment to prevent long-term scarring of the cornea.

Minimum

- Moxifloxacin eye drops 1 drop every 15 minutes for the first 2 hours after diagnosis, then 1 drop every hour while awake

- Initiate pain control as needed. DO NOT use topical anesthetics for pain control; they significantly impair corneal healing.

- Initiate teleconsultation with photographs.

- Activate evacuation (goal is ophthalmic care within 24 hours if lesion is large, central, or affects vision).

Better

- Obtain a culture before beginning treatment for sight-threatening or severe keratitis with suspected infection, such as large central corneal infiltrate that extends to the middle to deep stroma.20

- Provide intense loading dose of moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops 1 drop every 5–15 minutes for the first 30–60 minutes (patient can self-administer loading dose if reliable) after culture obtained.

- Treatment dose: 1 drop every 30–60 minutes around the clock until epithelial defect is closed.20

- Cycloplegic eye drop (cyclopentolate 1%), 1 drop every 8 hours for photophobia.

Best

- Real-time video telemedicine consultation

- Collagen corneal shield (national stock no. [NSN] 6515-01-482-9391) soaked in moxifloxacin drops for transport (generally 5–10 drops) and placed over the corneal infiltrate. This enables release of the medication to the ocular surface during transport, rather than administering repeated dosing.21

- No altitude restrictions for flight

NOTE: Topical steroid drops may be useful to reduce inflammation after the infection is controlled with topical antibiotics. Initiation of topical steroid drops should only be done under the direction of an eye care specialist after teleconsultation.

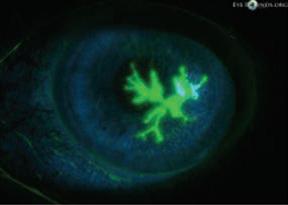

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis is an additional form of keratitis that usually occurs in patients with a history of previous episodes. HSV keratitis may demonstrate a specific dendritic staining pattern with fluorescein (Figure 19). After recognition, treatment can be initiated with oral acyclovir (400mg PO 5 times per day).

9. ANGLE-CLOSURE GLAUCOMA

Blockage of the normal flow of aqueous fluid in the anterior chamber of the eye will lead to increased IOP. If left untreated, blood flow to the posterior segment of the eye will be affected, leading to irreversible vision loss. The aqueous drain system can become blocked owing to anatomic variations, changes in lens size, inflammation, and trauma (Figure 20).

Goals

- Prompt diagnosis and identification, lowering of IOP.

- Minimum

- Diagnosis

- Pain (often described as a deep pain, similar to tooth pain)

- Decrease in or loss of visual acuity

- Photophobia

- Dull or cloudy appearance of the cornea due to corneal edema

- Fixed, mid-dilated pupil (usually occurs after IOP reaches 30–40mmHg)

- Increased IOP by palpation

- Acetazolamide 500mg PO initial dose, then 250mg PO every 4 hours to decrease IOP. (Note: contraindicated in patients with sickle cell trait.)

Initiate teleconsultation with photographs.

- Activate evacuation with goal of evaluation by an eye surgeon within 24 hours.

Better

- Oral acetazolamide plus topical IOP-lowering eye drops (timolol 0.5%, 1 drop twice a day in the affected eye).

- Administer antiemetics as required by patient symptoms (ondansetron 4mg ODT/IV/IO/IM every 8 hours as needed).

Best

- Topical corticosteroids (prednisolone acetate 1%) 1 drop every hour after consultation with ophthalmology or optometry.

- 3% hypertonic saline 250mL IV or mannitol 1g/kg over 30–60 minutes can be used to decease IOP if the aforementioned interventions are not effective.9

10. EYE CARE IN THE MULTITRAUMA / THERMAL BURN PATIENT

Patients with multisystem trauma who are intubated and sedated are at risk of developing corneal complications due to metabolic derangements and impaired ocular protective mechanisms.22 The presence of thermal facial burns puts the patient at high risk for exposure keratopathy. Loss of the normal blink reflex, impaired tear production, abnormal tear film dynamics, and incomplete eyelid closure, combined with the inability to relay ocular complaints all contribute to the development of exposure keratopathy and increase the risk for infectious keratitis.23 If there is no concern for OGI, ultrasound examination may be performed if personnel are equipped and trained. Patients with head and facial burns with eyelid involvement are especially prone to entropion (with burned eyelash stubs abrading the cornea) as well as exposure keratopathy from scar-related lid retraction and proptosis from orbital congestion (Figures 21 and 22).

SPECIFIC CONDITIONS (Continued)

Goal

Prevent ocular exposure and corneal injury in high risk patients.

Minimum

Initiate ocular surface protection with sterile petrolatum or methylcellulose drops to keep the ocular surface from drying out. (Do not substitute a nonophthalmic lubricant).

For thermal facial burns, instill erythromycin ophthalmic ointment or sterile petrolatum every 2 to 4 hours.

Better

Gentle horizontal taping of lids with hypoallergenic tape in conjunction with ocular surface protection to protect the eyes.24

Evaluate the eyes and instill a surface protectant at least every 8 hours. Ensure the surface of the eye is not dry, there is no pressure on the eye, pupil reactivity has not changed, and the eyelids are completely closed to protect the eye.

Best

- Detailed ocular evaluation

- Cover eyes with polyethylene film to prevent drying.

- Food-grade film is safe for use around the eyes.

- Apply from the eyebrow to the maxilla to ensure proper coverage

- No altitude restrictions for flight

NOTE: Surgilube should never be instilled into the eye as a lubricant, because if can cause corneal toxicity.18 When used for ultrasound examination, place a thin film (e.g., food-grade polyethylene or Tegaderm [3M, http://www.3m. com]) over the closed eyelid.

REFERENCES

- Joint Trauma System, Initial care of ocular and adnexal injuries by non-ophthalmologists at role 1, role 2, and nonophthalmic role 3 facilities CPG. 24 Nov 2014.

- Butler FK Jr. The eye in the wilderness. In: Auerbach P (ed.) Wilderness Medicine. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby; 2012.

- Joint Trauma System, Analgesia and sedation management during prolonged field care CPG, 11 May 2017.

- Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care. Tactical Combat Casualty Care guidelines for medical personnel. https://www.deployedmedicine.com/market/11/content/40 Accessed Mar 2018

- Peterson K, Colyer MH, Hayes DK, et al. Prevention of infections associated with combat-related eye, maxillofacial, and neck injuries. J Trauma. 2011;71:S264–S269.

- Bhagat N, Nagori S, Zarbin M. Post-traumatic infectious endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56:214–251.

- Ord RA. Postoperative retrobulbar haemorrhage and blindness complicating trauma surgery. Br J Oral Surg.1981;19:202–207.

- Lima V, Burt B, Leibovitch I, et al. Orbital compartment syndrome: the ophthalmic surgical emergency. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54: 441–449.

- Harju M, Kivela T, Lindbohm N, et al. Intravenous hypertonic saline to reduce intraocular pressure. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2013;91:625–629.

- Wood CM. The medical management of retrobulbar haemorrhage complicating facial fractures: a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;27:291–295.

- Walton W, Von Hagen S, Grigorian R, et al. Management of traumatic hyphema. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:297–334.

- Fong LP. Secondary hemorrhage in traumatic hyphema. Predictive factors for selective prophylaxis. Ophthalmology. 1994;101: 1583–1588.

- Albiani DA, Hodge WG, Pan YI, et al. Tranexamic acid in the treatment of pediatric traumatic hyphema. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43:428–431.

- Mervin K, Valter K, Maslin J, et al. Limiting photoreceptor death and deconstruction during experimental retinal detachment: the value of oxygen supplementation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:155–164.

- Rapp J, Plackett TP, Crane J, et al. Acute traumatic wound management in the prolonged field care setting. J Spec Oper Med. 2017;17(2):132–149.

- Long J, Tann T. Orbital trauma. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15;249–253.

- Colby K. Chemical injuries of the cornea. Focal Points: Clinical Modules for Ophthalmologists. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2010, module 1.

- Sawyer WI, Burwick K, Jaworski, et al. Corneal injury secondary to accidental Surgilube exposure. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129: 1229–1230.

- Sharifipour F, Baradaran-Rafii A, Idani E, et al. Oxygen therapy for acute ocular chemical or thermal burns: a pilot study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:823–828.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cornea/External Disease Panel, Hoskins Center for Quality Eye Care. Cornea/external disease summary Benchmarks—2016. https:// www.aao.org/summary-benchmark-detail/cornea-external -disease-summary-benchmarks-2016.

- Willoughby CE, Batterbury M, Kaye SB. Collagen corneal shields. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:174–182.

- Grixti A, Sadri M, Datta AV. Uncommon ophthalmologic disorders in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2012;27:746. e9–22.

- Saritas TB, Bozkurt B, Simsek B, et al. Ocular surface disorders in intensive care unit patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013: 182038.

- Stevens S. Taping an eyelid closed. Community Eye Health. 2012; 25(78):36.

- van Wyck D, Loos PE, Friedline N, et al. Traumatic brain injury management in prolonged J Spec Oper Med. 2017;17 (3):130–140.

APPENDIX A: RELATIVE AFFERENT PUPILLARY DEFECT

APPENDIX B: USE OF THE DIRECT OPTHALMOSCOPE

The direct ophthalmoscope is designed to use the patient’s own optical system to magnify the optic disc and retina for diagnostic purposes, but it has multiple additional uses, such as obtaining a magnified view of the anterior segment, evaluating for visually significant cataract, and evaluating pupil responses in uncooperative or pediatric patients.

Equipment: Direct Ophthalmoscope

Techniques:

- To obtain a magnified view of the anterior segment of the eye. Viewing from 2-3 inches from the eye using the plus lenses (black or green numbers, ~5) will provide an enlarged view when evaluating for foreign bodies or corneal abrasions. Using the cobalt blue filter with fluorescein dye will enhance the view of corneal epithelial defects.

- To evaluate for cataracts, stand approximately 1 meter from the patient and evaluate the red reflex from the retina with no lens dialed in (no red or green numbers). Blockage of the red reflex will highlight any visually significant cataracts.

- To check for pupil reactivity in uncooperative patients or children, view the red reflex from 2-3 feet (again with no lenses dialed in); movie the light from one eye to the other and observe the change in the size of the red reflex.

- Assessment of retinal spontaneous venous pulsations may be possible in the setting of traumatic brain injury.25

APPENDIX C: BASIC OCULAR EXAMINATION

APPENDIX D: PACKING AND PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS

Minimum Equipment

- Rigid Eye shield

- Lateral canthotomy/cantholysis instrument set

- Bright light source

- Visual acuity estimate reference

- Teleconsultation capability

Minimum Medications

- Moxifloxacin 400 mg oral tablets or Levofloxacin 750 mg oral tablets

- Clindamycin 300 mg oral tablets

- Ketamine IV

- Odansetron oral dissolving tablets or IV

- Tetracaine eye drops or 2% lidocaine without epinephrine (unpreserved)

- Fluid for ocular irrigation

- Fluorescein ophthalmic stain

Better Equipment

- Ice packs

- Direct ophthalmoscope

- Hypoallergenic tape

Better Medications

- IV ertapenem 1 gm

- Oxymetazoline HCL nasal spray

- Erythromycin ophthalmic ointment

- Cyclopentolate hydrochloride 1% eye drops

- Moxifloxacin 0.5% ophthalmic drops

Best Equipment

- Collgen eye shields (NSN 6515-01-482-9391)

- Steristrips

- Polyethylene film (food grade)

- Oxygen source

- Urine test strips

- Portable ultrasound with linear probe

Best Medications

- Mannitol IV

- Acetazolamide 250mg oral tablets

- Corticosteroids IV

- Timolol 0.5% eye drops

- Prednisolone acetate 1% eye drops

- Preservative-free artificial tears

- Tobramycin/dexamethasone combination eye drops (tobradex)

- Acyclovir 400 mg oral tablets

- Vitamin C

- Tetanus vaccine

- Human rabies immune globulin and rabies vaccine

APPENDIX E: OCULAR INJURIES & VISION THREATENING CONDITIONS SUMMARY TABLE

• Maintain high suspicion for ocular injuries.

• Assess and document visual function.

• Examine for critical physical findings.

• Maintain patient comfort and prevent further injury (e.g., pain medication, anti-emetic, eye shield, elevate head 30º-45º).

• Establish telemedicine contact with eye care specialist; provide photographs or real-time video.

• For eyesight-threating conditions, prioritize evacuation with goal to arrive at an eye surgeon or eye specialist within 24 hours.

• Provide optimal Role 1 care when evacuation goal cannot be met

Goal-Prevent further damage to the eye, prevent infection in the eye (endophthalmitis), and evacuate to an eye surgeon as soon as possible.

Minimum-Rigid shield, pain control, antiemetic, raise head 30º-45 º. Antibiotic prophylaxis: moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily or ertapenem 1g IV/IO daily.

Better-Add clindamycin 300 mg PO or IV/IO every 8 hours to endophthalmitis prophylaxis.

Best-Detailed ocular exam every 4 hours. Coordinate surgical care within 8 hours of injury.

Ultrasound is contraindicated for suspected OGI because it places pressure on the eye.

Goal-Lower the orbital compartment pressure as soon as possible to prevent tissue damage.

Minimum-Prompt recognition (i.e., bulging of eye, increased pressure by palpation, decreased vision, +RAPD). Lateral canthotomy/cantholysis (LCC) within 90 minutes of injury (if evacuation to surgical capability will take more than 60 minutes). Pain control, antiemetic, raise head 30º-45 º.

Better-Minimize patient movement, ice packs, monitor for return of increased intraorbital pressure (IOP).

Best-If rebleeding after initial response to lateral canthotomy/cantholysis, acetazolamide 500mg PO once then 250mg PO 4 times per day. If unable to take PO, 3% hypertonic saline 250ml IV or mannitol 1 g/kg IV over 30-60 minutes. Corticosteroid (e.g. 1g methylprednisolone IV once).

Relative afferent pupilary defect (RAPD), abnormal dilation of pupil when light is shined into injured eye.

LCC is a vision-saving procedure with minimal risk of causing additional ocular injury. When in doubt, perform LCC.

Goal-Identify significant ocular injuries; protect the eye from further injury.

Minimum-Document vision, pain control. Prevent further damage with rigid shield, anti-emetic, raise head 30º-45º.

Best-Hyphema (anterior chamber injury): Topical steroid eye drop (prednisolone acetate 1% 4 times per day) and cycloplegic drop (cyclopentolate 1% 1 drop every 8 hours). Monitor vision and IOP. Treat elevated IOP with timolol eye drops 0.5%, 1 drop twice a day or acetazolamide 500mg PO once then 250mg po 4 times per day. (Note: contraindicated in patients with sickle cell trait). If unable to take PO, 3% hypertonic saline 250ml IV or mannitol 1 g/kg IV over 30-60 minutes.

Best-Retina/optic nerve (posterior chamber injury): Supplemental oxygen. Perform careful ultrasound and transmit images with telemedicine consult.

Goal-Prevent infection, protect the eye from further injury.

Minimum-Maintain high suspicion for open globe injury (treat as such if suspected). Keep injured eyelid tissue moist by covering with polyethylene film (food grade).

Better-For foreign body penetration, animal bite, or laceration with visible orbital fat, start antibiotic: moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875mg/125mg PO every twelve hours or ertapenam 1 gm IV/IO daily.

Best-Detailed ocular exam. Irrigate and perform temporary closure of wounds. Tetanus and rabies prophylaxis if indicated.

Goal-Evaluate for concurrent open or closed globe injury and prevent long-term complications.

Minimum-Maintain high suspicion for open globe injury. No nose blowing. Pain control, antiemetic, raise head 30º-45º.

Better-Antibiotic moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875mg/125mg PO every twelve hours or ertapenam 1 gm IV/IO daily. Initiate nasal decongestant (e.g., Afrin nasal spray twice a day for 3 days) or oral decongestant (e.g., pseudoephedrine 30mg every 6 hours).

Best-Detailed ocular exam. Ice pack for 20 min every 1-2 hours for first 48 hours. Monitor for delayed onset of OCS requiring LCC.

Goal-Initiate eye irrigation as quickly as possible to reduce damage to the eye, treat the injury to minimize scarring and loss of vision.

Minimum-Immediate irrigation with IV fluid, sterile water, or clean water with at least 2L of fluid. Remove any particulate matter using a cotton tip applicator.

Better-Continue irrigation until pH=7, verified using urine test strip.

Best-Grade I - erythromycin ophthalmic ointment, cyloplegic drops (cyclopentolate 1%), lubrication with artificial tears.

Best-Grade II-IV - topical antibiotic drops (moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops, 1 drop every 8 hours), topical corticosteroid (tobradex or prednisolone acetate 1%, 1 drop every hour while awake), doxycycline 100 mg po every 12 hours, Vitamin C 2g 4 times per day, 100% O2 for 1hr twice daily.

Goal-Recognize infection early and start appropriate antibiotics; evacuate suspected cases of orbital cellulitis to an eye surgeon as rapidly as possible

Minimum-Preseptal: Moxifloxacin 400mg PO daily or levofloxacin 750mg PO daily. Does not cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA); follow closely for worsening condition.

Minimum-Orbital: IV antibiotics: ertapenem, 1 g IV/IO daily or levofloxacin 500mg IV once a day.

Better-Orbital: Add nasal decongestant (e.g. Afrin nasal spray twice a day for 3 days) or oral decongestant (e.g., pseudoephedrine 30mg every 6 hours).

Best-Preseptal: Trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole DS 1 tablet PO every 8 hours combined with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875mg every 12 hours.

Best-Orbital: Continue IV antibiotics. Monitor vision every 4 hours until evacuation.

Goal-Prompt recognition and treatment to minimize scarring and loss of vision.

Minimum-Moxifloxacin eye drops 1 drop every 15 minutes for first 2 hours, then 1 drop every hour while awake.

Better-Obtain a culture prior to beginning treatment for sight-threatening keratitis; intense loading dose of moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drops 1 drop every 5-15 min for the first 30-60 minutes (patient can self-administer loading dose if reliable) after culture obtained; then 1 drop every 30-60 minutes around the clock until epithelial defect is closed; cycloplegic eye drop (cyclopentolate 1%), 1 drop every 8 hours for photophobia.

Best-Collagen corneal shield soaked in moxifloxacin drops for transport (5-10 drops) placed over the corneal infiltrate.

Goal-Prompt recognition and treatment to decrease intraocular pressure.

Minimum-Diagnose based on signs and symptoms: pain, decreased vision, photophobia, dull or cloudy cornea, fixed mid-dilated pupil, increased IOP by palpation. Acetazolamide 500 mg PO initial dose, then 250mg PO every 4 hours to decrease IOP.

Better-Oral acetazolamide plus topical IOP-lowering eye drops (timolol 0.5%, 1 drop twice a day in the affected eye), antiemetic as needed.

Best-Topical corticosteroid (prednisolone acetate 1%) 1 drop every hour after consultation with eye specialist. IV medication for refractory cases (3% hypertonic saline 250ml IV or mannitol 1 g/kg over 30-60 min).

Goal-Prevent ocular exposure and corneal injury in high-risk patients.

Minimum-Keep the ocular surface from drying out using lubricants: sterile petrolatum or methylcellulose drops (do not substitute a non-ophthalmic lubricant). For burns, erythromycin ophthalmic ointment or sterile petrolatum every 2-4 hours.

Better-Horizontal taping of eyelids to protect eyes. Evaluate the eyes and instill a lubricant every 8 hours.

Best-Conduct a detailed ocular exam and cover eyes with food grade polyethylene film to protect eyes.

Surgilube should never be instilled into the eye as a lubricant due to corneal toxicity. When used for ultrasound examination, place a thin film over the closed eyelid.

APPENDIX F: ADDITIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING OFF-LABEL USES IN CPGS

PURPOSE

The purpose of this Appendix is to ensure an understanding of DoD policy and practice regarding inclusion in CPGs of “off-label” uses of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products. This applies to off-label uses with patients who are armed forces members.

BACKGROUND

Unapproved (i.e., “off-label”) uses of FDA-approved products are extremely common in American medicine and are usually not subject to any special regulations. However, under Federal law, in some circumstances, unapproved uses of approved drugs are subject to FDA regulations governing “investigational new drugs.” These circumstances include such uses as part of clinical trials, and in the military context, command required, unapproved uses. Some command requested unapproved uses may also be subject to special regulations.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION REGARDING OFF-LABEL USES IN CPGs

The inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is not a clinical trial, nor is it a command request or requirement. Further, it does not imply that the Military Health System requires that use by DoD health care practitioners or considers it to be the “standard of care.” Rather, the inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is to inform the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner by providing information regarding potential risks and benefits of treatment alternatives. The decision is for the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner within the practitioner-patient relationship.

ADDITIONAL PROCEDURES

Balanced Discussion

Consistent with this purpose, CPG discussions of off-label uses specifically state that they are uses not approved by the FDA. Further, such discussions are balanced in the presentation of appropriate clinical study data, including any such data that suggest caution in the use of the product and specifically including any FDA-issued warnings.

Quality Assurance Monitoring

With respect to such off-label uses, DoD procedure is to maintain a regular system of quality assurance monitoring of outcomes and known potential adverse events. For this reason, the importance of accurate clinical records is underscored.

Information to Patients

Good clinical practice includes the provision of appropriate information to patients. Each CPG discussing an unusual off-label use will address the issue of information to patients. When practicable, consideration will be given to including in an appendix an appropriate information sheet for distribution to patients, whether before or after use of the product. Information to patients should address in plain language: a) that the use is not approved by the FDA; b) the reasons why a DoD health care practitioner would decide to use the product for this purpose; and c) the potential risks associated with such use.