Intro to TCCC

JTS / CoTCCC

TCCC

From its humble beginnings as a Naval Special Warfare biomedical research effort to a joint US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) and Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences (USUHS) research project, TCCC has led a systematic review of all aspects of battlefield trauma care into a set of guidelines designed to combine good medicine with good small-unit tactics. Today, and after nearly two decades of combat operations, the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care and the Joint Trauma System continuously reviews casualty data, best practices, lessons learned, research projects and medical literature to produce a set of evidence-based, best-practice prehospital trauma care guidelines customized for use on the battlefield.

The overall objective of TCCC is to teach service members how to effectively treat combat casualties while preventing additional casualties and completing the mission at hand. The three phases of TCCC include care under fire, tactical field care and tactical evacuation care.

* Care Under Fire (CUF) outlines strategies using limited medical equipment to render care at the point of injury while the first responder and the casualty are still under hostile fire.

* Tactical Field Care (TFC) provides casualty care guidelines once the first responder and the injured combatant are no longer under hostile fire.

* The Tactical Evacuation Care (TACEVAC) phase begins once the casualty has been transferred to a transport aircraft or vehicle. During this phase additional medical personnel and equipment may be available to provide augmented casualty care.

TCCC has been shown to be very effective in saving lives on the battlefield. For this reason in 2005, the United States Special Operations Command required TCCC training for all deploying combatants and not just medical personnel. The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have enabled the US Military to make numerous advances in battlefield care. This module will explain what TCCC is and why you need to learn about it. Our military presently has the best casualty treatment and evacuation system in history. TCCC is what will keep you alive long enough to benefit from it.

The key elements of TCCC include:

- Aggressive use of tourniquets

- Hemostatic dressings

- Aggressive needle thoracostomy

- Airway positioning

- Surgical airways for maxillofacial trauma

- Tactically appropriate fluid resuscitation

- IVs only when needed/IO access if required

- Improved battlefield triple-option analgesia

- Battlefield antibiotics

- Hypothermia prevention

- Combine good tactics and good medicine

- Scenario-based training

- Combat medic input to guidelines

Video

Introduction

For U.S. military service members wounded on the battlefield, the most critical phase of care is the period from the time they are injured until they arrive at a medical treatment facility (MTF) capable of providing the surgical care they need. If a casualty survives long enough to reach the care of a combat trauma surgeon, the likelihood is very high that he or she will survive. Almost 90% of our service men and women who die from combat wounds do so before they arrive at an MTF. This fact highlights the importance of the battlefield trauma care provided by combat medics, corpsmen, and pararescuemen (PJs) as well as nonmedical unit members in improving the survival of our country’s combat wounded.

Prehospital trauma care on the battlefield varies in many respects from prehospital trauma care as practiced in the civilian sector. The types and severity of the injuries are different from those encountered in civilian settings, and combat medical personnel face multiple additional challenges in caring for their wounded teammates in tactical settings. They must provide care while under hostile fire, often working in the dark, with multiple casualties and limited equipment. In addition, they must often contend with prolonged evacuation times as well as the need for tactical maneuvers superimposed on their efforts to render care. Treatment guidelines developed for the civilian setting do not necessarily translate well to the battlefield. Preventable deaths and unnecessary additional casualties may result if the tactical environment is not considered when developing battlefield trauma care strategies

These considerations notwithstanding, at the onset of hostilities in Afghanistan, most U.S. combat medical personnel were being trained using the following civilian-based principles of trauma care:1

- Rendering care with no structured consideration of the evolving tactical situation

- No use of tourniquets to control extremity hemorrhage

- Managing external hemorrhage with prolonged direct pressure, precluding the medic from attending to other injuries or rendering care to other casualties

- No use of hemostatic dressings

- Two large-bore intravenous lines (IVs) started on all patients with significant trauma

- Treatment of hypovolemic shock with large-volume crystalloid fluid resuscitation

- No special considerations for traumatic brain injury (TBI) with respect to avoiding hypotension or hypoxia

- Management of the airway in facial trauma or unconscious casualties with endotracheal intubation

- No specific techniques or equipment to prevent hypothermia and secondary coagulopathy in combat casualties

- Management of pain in combat casualties with intramuscular (IM) morphine—a battlefield analgesic that dates to the Civil War

- No intraosseous (IO) access

- No prehospital electronic monitoring

- No effective nonparenteral analgesic medications

- No prehospital antibiotics

- No delineation of which casualties might benefit most from supplemental oxygen during tactical evacuation

- Spinal precautions applied broadly to casualties with significant trauma, without consideration of tactical concerns or mechanism of injury

Guidelines and Key Points

Prehospital trauma care in tactical settings is very different from civilian settings. Tactical and environmental factors have a profound impact on trauma care rendered on the battlefield. Good medicine can be bad tactics.

Good first responder care is critical. Up to 28% of combat deaths today are potentially preventable, so good battlefield care is paramount in avoiding preventable deaths. Improvements in how we approach the combat casualty have resulted in significantly lower death rates in combat. TCCC is different from civilian trauma care training you may have received in the past, but TCCC will give you the tools you need!

The Three Phases of Care in TCCC are:

Care Under Fire

- Care Under Fire is the very limited care that can be provided while the casualty and the provider are under effective enemy fire.

Tactical Field Care

- Tactical Field Care is performed on the battlefield, but not under effective enemy fire.

TACEVAC Care

- Tactical Evacuation Care is rendered during transport off the battlefield on the way to more definitive care

Tourniquets Reconsidered and the Need for TCCC

Extremity hemorrhage had been reported to be a leading cause of preventable death on the battlefield during the Vietnam conflict.3,6 Despite this fact, in 1992, U.S. military combat medics, corpsmen, and PJs were not being taught to use a readily available and highly effective treatment for extremity bleeding—a tourniquet.7-9 This realization led to a systematic review of all aspects of battlefield trauma care. This project was conducted from 1993 to 1996 as a joint effort of Special Operations medical personnel and the Uniformed Services University. This 4-year research effort culminated with the publication of the original TCCC paper in 1996.5,8,9

The Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care

The need for periodic updates to the TCCC Guidelines was recognized early in the development of TCCC. The original TCCC paper recommended that the TCCC Guidelines be updated as needed by a DoD-sponsored committee established for this purpose.5 This concept was endorsed by the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), and the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC) was subsequently funded in 2001 as a USSOCOM Biomedical Research Program. The command chosen to execute this project, the Naval Operational Medicine Institute, subsequently conducted the necessary coordination with Navy medicine leaders to ensure that there would be long-term support of this effort. BUMED programmed for financial and personnel support of the CoTCCC beginning in fiscal year 2004. In fiscal years 2007 through 2009, the Office of the Surgeon General of the Army, the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research, and the Defense Health Board (DHB) also provided substantial support for the CoTCCC.

Because the goal of TCCC is to provide the best possible medical care consistent with good small-unit tactics, it is essential that the membership of the CoTCCC include combat medical personnel as well as physicians. It is also critical to have tri-service representation to ensure that differences in doctrine and experience between the Army, Navy, and Air Force medical departments are identified and best practices from each are incorporated into TCCC. The combat medics selected include Navy SEAL corpsmen, Navy corpsmen assigned to Marine units, Ranger medics, Special Forces 18-D medics, Air Force pararescuemen, Air Force aviation medics, and Coast Guard health specialists. Physician membership includes representatives from the trauma surgery, emergency medicine, critical care, and operational medicine communities. Physician assistants, medical planners

In 2007, due to the increasing visibility of TCCC in the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), the Navy Medical Support Command proposed that the CoTCCC be moved to a more senior joint command. This proposal was briefed to the offices of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs and the Surgeon for the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

In March 2008, the CoTCCC was relocated to function as a working group of the Trauma and Injury Subcommittee of the Defense Health Board (DHB). The DHB is chartered to provide independent advice and recommendations to the Secretary of Defense through the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs on medical issues, including the care of U.S. service members wounded in combat operations.

Later, on 21 February 2013, by Direction of the Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, the CoTCCC was moved once more, this time to the Joint Trauma System (JTS) to have it co-located with the DoD’s combat trauma management system. In 2017, Congress made the JTS the DoD’s lead agency for trauma, and the CoTCCC is the prehospital component of the JTS.

Since 2001, and throughout these organizational changes, the CoTCCC has continued to monitor developments in prehospital trauma care. The TCCC Guidelines are updated based on: (1) ongoing review of the published civilian and military prehospital trauma literature; (2) ongoing interaction with military combat casualty care research laboratories; (3) direct input from experienced combat corpsmen, medics, and PJs; (4) input from the service Medical Lessons Learned Centers; (5) case reports discussed at the weekly Joint Theater Trauma System (JTTS)process improvement video teleconferences; (6) observations on the causes of death in combat fatalities gleaned from JTS-Armed Forces Medical Examiner System (AFMES) conferences; and (7) expert opinion from both military and civilian trauma experts.

Each change to the TCCC Guidelines is now supported by a change paper published in the Journal of Special Operations Medicine. Guideline changes are also included in revisions of the PHTLS textbook.21,22

As the use of TCCC spread from the U.S. military to other agencies within the federal government, allied nations, and the civilian sector, it became important to include representatives from these groups in the TCCC update process, both to secure the benefit of their input and to facilitate communication between them and the CoTCCC. Accordingly, the CoTCCC began to invite liaison members from these groups to participate in its combat trauma care performance improvement process. The CoTCCC voting members and CoTCCC liaison members collectively comprise the TCCC Working Group, and it is through the untiring efforts of this group that the TCCC Guidelines and other TCCC knowledge products have remained state of the art through 16 years of conflict.8,21

Although the TCCC Guidelines are best-practice trauma care guidelines customized for use on the battlefield, they are only guidelines. There are no rigid protocols in combat, including TCCC. If the recommended TCCC combat trauma management plan does not work for the specific tactical situation that a combat medic, corpsman, or PJ encounters, then care must be modified to best fit the tactical situation. Scenario-based planning, then, is critical for success in TCCC.5,13

Changing the Culture in Battlefield Trauma Care

Several events that occurred prior to the onset of hostilities in Afghanistan were central to this transformation of battlefield trauma care. The Navy SEAL teams and the 75th Ranger Regiment began training all combatants in TCCC prior to the start of the current conflicts. The Army Special Missions Unit and the Air Force pararescue community also implemented TCCC from 1997 to 1998 and quickly adopted the practice of teaching TCCC to every combatant so that the most critical lifesaving interventions, like tourniquets, can be accomplished by every one of their unit members.9,50,51

After 10 years of intense combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan by the Ranger Regiment, Kotwal and colleagues reported only one potentially preventable death among 32 combat fatalities (out of 419 casualties) sustained by the 75th Rangers,51 and the death that was deemed preventable occurred in the hospital, not the prehospital, setting. This finding stands in stark contrast to the 15% to 28% of preventable deaths reported in other studies among U.S. casualties in these conflicts.27,32,34Considering the prehospital phase only, potentially preventable deaths among fatalities in the 75th Rangers was zero as compared to 24% in the study by Eastridge et al.32 The remarkable disparity in potentially preventable deaths between early adopters of TCCC and the rest of the U.S. military was not widely known until the Kotwal study was published in 2011, followed by the Eastridge study in 2012. Observed differences in potentially preventable deaths may be due to differences in the methodology of determining which deaths are considered potentially preventable or differences between the casualty cohorts reported. Nevertheless, in 2017 little disagreement that the interventions pioneered by TCCC reduce preventable deaths during the phase of care when they are most likely to occur has been offered.

As noted earlier, the transition from previous prehospital trauma care regimens to TCCC was well under way in the U.S. military by 2011. This happened because of a very specific sequence of events that has been well documented but is not widely known. When U.S. forces invaded Afghanistan in 2001, there was no JTS in place and thus no mechanism for the systematic review of combat casualty care outcomes in the U.S. military to seek opportunities to improve care.52 Specifically, from 2001 to 2004, there was no DoD focus on the causes of preventable deaths among U.S. fatalities and how they could have been prevented, and TCCC was primarily used only by those units that had adopted these new concepts before 2001. Adoption of TCCC required a move away from long-standing and firmly entrenched approaches to battlefield trauma care. How did this widespread change of culture finally come about?

The first and most fundamental requirement for changing the culture in battlefield trauma care was to provide a much higher-quality set of recommendations. As recounted in recent publications,8,9,21 there were three aspects of the TCCC development process that enabled these improved recommendations. First, during the research effort that led to the development of TCCC, existing recommendations for prehospital combat trauma care were held to the same standards of evidence as those applied to proposed changes to that care. Second, the actual conditions that combat medical personnel were likely to encounter on the battlefield were considered in developing the new recommendations. Finally, input from combat medics, corpsmen, and PJs, our country’s primary battlefield trauma care providers, was sought and incorporated throughout the TCCC development process.

The second step in changing the culture in battlefield trauma care, and the one that first led to the spread of TCCC beyond the few early adopters, was the first preventable death review of U.S. fatalities from Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2004, the USSOCOM had two critically important questions that needed to be answered: (1) what specifically were our Special Operations combat casualties dying from, and (2) what, if anything, could have been done to prevent those deaths? One might reasonably assume that the DoD had always performed preventable death reviews on its combat fatalities, but, as of 2004, there was no formal process to review combat deaths and to use that information to save the lives of future casualties. USSOCOM called upon Col. John Holcomb, who was then the Commander of the USAISR, to help answer these questions. Col. Holcomb’s team found that in Special Operations forces, 15% of combat deaths resulted from injuries that were potentially survivable, and a number of those deaths might have been prevented with simple TCCC measures like a tourniquet.27 This study sent a clear signal that TCCC training and equipment were needed throughout the Special Operations community, as was methodology for an ongoing evaluation of the impact of these new battlefield trauma care techniques on morbidity and mortality.

The third step in changing the culture also resulted from a collaboration between USSOCOM and USAISR. After the documentation of preventable deaths in the Holcomb study, the leadership of USSOCOM supported the TCCC Transition Initiative, which expedited TCCC equipping and training of deploying USSOCOM units. The project was led by an 18-D Special Forces medic, SFC Dominic Greydanus, and not only provided TCCC trainingand equipment to deploying Special Operations units, but also collected feedback from medics, corpsmen, and PJs when these units returned from combat operations. It also provided early documentation of the success of TCCC interventions.8,21,37

The fourth event that led to the widespread adoption of TCCC concepts was a U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) message that required that all combatants deploying to that theater be equipped with a tourniquet and a hemostatic dressing. This requirement was driven by the CENTCOM Surgeon at the time, Lt. Gen. Doug Robb. Although the services have the primary responsibility for training and equipping combatants, this mandate from CENTCOM forced supervising medical officers throughout the services to rethink their many years of medical training that had consistently taught them that the use of extremity tourniquets was a very bad idea.

The fifth key element that helped to change the culture of battlefield trauma care in the military was the excellent documentation of the impact of tourniquet use. It is often difficult to identify with precision which elements of TCCC are responsible for saved lives, but tourniquets are an exception to this rule. The work of Col. John Kragh, an orthopedic surgeon working at the Ibn Sina Hospital in Baghdad, reported that 31 lives were saved with tourniquets at his facility in one 6-month period.8,28-30 This finding, when extrapolated to all U.S. casualties sustained in Iraq and Afghanistan up to that point in time, indicated that, as early as 2008, well over 1,000 U.S. service members’ lives had possibly been saved with tourniquets in those conflicts. Again, these successes with tourniquet use were obtained without loss of limbs to tourniquet ischemia. Col. Kragh’s work irrefutably confirmed the lifesaving benefits of what was perhaps the single most controversial aspect of TCCC.8

The sixth essential step in changing the culture of the U.S. military to accept TCCC was effective strategic messaging. The success of the TCCC Transition Initiative, Col. Kragh’s work, and the decreased incidence of preventable deaths in units that were early TCCC adopters were presented frequently at military medical conferences and in the published medical literature.29,30,33,36,37,42,44,45,47 The dramatically lower proportion of preventable deaths in the 75th Ranger Regiment compared to that in the broader U.S. military in which TCCC was adopted later was widely acclaimed in the medical literature. This acclamation increased awareness among combat medical personnel and their physician and physician assistant supervisors of the success of TCCC in reducing preventable deaths. These reports also provided TCCC innovators with published evidence that they could present to their unit commanders.32,51

Finally, evidence alone is often not effective in driving advances in trauma care,21 and this and other difficulties inherent in making changes in battlefield trauma care have been identified.52,53 Divided lines of authority and distributed responsibilities in the military structure make it exceedingly difficult to optimize battlefield trauma care throughout the DoD. Butler, Smith, and Carmona described the problem this way:52

“Just as the United States has hundreds of trauma centers and thousands of autonomous prehospital care systems, which can potentially slow the transition of advances in military prehospital trauma care into use in the civilian sector, the U.S. Military has four armed services, six Geographic Combatant Commands, the U.S. Special Operations Command and the U.S. Transportation Command, all of which play a role in the care of combat casualties. Each of these organizations is authorized to operate autonomously with respect to combat casualty care unless directives are issued at the highest level of the military chain of command, which is the Secretary of Defense (SecDef) acting on the advice of his or her chief medical advisor, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. Lacking direction in the form of SecDef rule and Joint Staff doctrine, there is no assurance that advances in trauma care will be implemented consistently throughout the various components of the US Military.”

Unfortunately, at the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Service leadership levels, the span of responsibilities is immense. The ability of leaders at this level to focus on and mandate aspects of trauma care that are vigorously debated even among trauma subject matter experts is very limited. Therefore, when change is effected in battlefield trauma care, it typically occurs at a significantly lower level in the military chain of command and benefits only those individuals in that part of the organization.

When TCCC was first proposed in 1996, the recommendations contained in the TCCC Guidelines were presented to a great many people in both civilian and military medical audiences. Even so, very little happened until Rear Admiral Tom Richards, then the Commander of the Naval Special Warfare Command, examined the evidence presented to him and mandated the use of TCCC throughout the Navy SEAL community. Admiral Richards was not a doctor, but his decision paved the way for saving hundreds of lives among U.S. combat casualties.8,9,21

A similar occurrence took place in the 75th Ranger Regiment. In 1997, the regiment’s commander, Col. Stanley McChrystal, acting on the advice of his Ranger medical personnel, made caring for Rangers wounded in combat one of his “Big Four” priorities by directive in 1997. The Big Four were marksmanship, physical training, small unit tactics, and . . . medical readiness.51 Col. McChrystal understood that on the field of battle, everyone has the potential to be a casualty, and everyone—not just medics—may be the first to encounter a casualty and to render lifesaving care. He expected that every Ranger was going to be engaged in casualty care, and so every Ranger received training in TCCC.21,54

Likewise, Gen. Doug Brown and VADM Eric Olson at the U.S. Special Operations Command mandated TCCC at a time when it was not the standard of care for prehospital trauma care, either in the U.S. military or in the civilian sector. General John Abizaid at the CENTCOM did much the same thing in requiring the use of tourniquets in Iraq and Afghanistan at a time when conventional wisdom dictated otherwise.

The first takeaway from this discussion of the importance of leadership in advancing battlefield trauma care is that new evidence alone does not drive advances in trauma care—in either the civilian sector or the military—people do that.

The second takeaway is that it is often not trauma subject matter experts who are the final decision makers in introducing new standards of trauma care. Both in the military and in the civilian sector, decision makers at senior levels are often not the subject matter experts. As former U.S. Surgeon General Rich Carmona pointed out during the Hartford Consensus IV meeting,55 it is the responsibility of innovative trauma care experts to inform and inspire senior leaders so that advances in trauma care can be resourced and implemented. It was the senior leaders noted here—all combat commanders, not physicians—who mandated that TCCC be implemented in the military. Effecting positive change in trauma care therefore takes strong senior leaders—acting on the advice of well-informed trauma subject matter experts—with a dedication to continuously improving trauma care and a willingness to invest both their professional reputations and resources to do so.21,54

From the Battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan to Worldwide Use

Historically, many lessons learned from military combat casualty care have found application in civilian trauma care. This has also been true of TCCC. The United States has just had the longest period of continuous armed conflict in its history, and this has created a unique opportunity to understand and improve battlefield trauma care. Over the past 16 years of caring for combat casualties, many advances have been incorporated into TCCC as new evidence, new technology, and ongoing battlefield experience have accumulated. Many published reports from this period have highlighted the success of TCCC, and it is now used well beyond the U.S. military.

TCCC has now been implemented by many coalition partnernations1 and has been recommended as the standard of care for combat first-aid training in member nations by the ABCANZ Armies (formerly America, Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand Armies’ Program).74 Canada was one of the earliest international adopters of TCCC. Savage and colleagues noted that, “although the Canadian military experienced increasingly severe injuries during the current conflicts, the Canadian Forces have experienced the highest casualty survival rate in history.”38 They further reported, “Though this success is multifactorial, the determination and resolve of CF leadership to develop and deliver comprehensive, multileveled TCCC packages to soldiers and medics is a significant reason for that and has unquestionably saved the lives of Canadian, Coalition, and Afghan Security Forces.” TCCC was also recommended as the battlefield trauma care standard for NATO partner nations by the NATO Special Operations–convened Human Factor and Medicine Expert Panel 224in 2011.75 Thanks in large part to allied participation in the TCCC Working Group and to the NAEMT’s worldwide educational infrastructure and its leadership in offering TCCC training to countries all around the world,21,73TCCC has indeed spread “all around the globe.”76

In 1996, the nascent TCCC effort benefitted from an interaction between Rear Admiral Mike Cowan, Commander of the Defense Medical Readiness Training Institute, and Dr. Norman McSwain, founder and medical director of the PHTLS program. These two leaders agreed that there should be a military medicine section in the fourth edition of the PHTLS textbook. TCCC concepts were included in that edition 77 and in every subsequent edition. This has been exceptionally helpful in that the PHTLS textbook carries the endorsement of the ACS and the NAEMT; this was the first step toward the mainstreaming of TCCC.8,9 Beginning with this initial interaction, a robust and ongoing dialogue developed between TCCC, PHTLS, and NAEMT. The strong partnership between NAEMT, PHTLS, the ACS-COT, and TCCC has endured, and these groups have adopted a number of the recommendations made by the CoTCCC regarding prehospital trauma care.78,79 TCCC, in turn, has benefitted greatly from many aspects of the PHTLS program and the NAEMT educational infrastructure.21,73

In recent years, civilian law enforcement officers and EMS responders have been called to bombing incidents, school and mall shootings, and other terror attacks that present tactical situations similar in some respects to those encountered on battlefields. The threat of ongoing hostile fire, treating multiple casualties under cover, and prolonged evacuation times have all come into play. Even in urban settings, getting to, treating, and transporting casualties scan require tactics and training outside the parameters of many standard EMS protocols. The mass casualty incidents at Columbine High School, Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook Elementary School, Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, and the Las Vegas concert shooting are examples in point. More widespread adoption of applicable TCCC Guidelines into tactical EMS training programs, and application of these principles to tactical law enforcement operations may result in better tactical flow and additional lives saved.80

The dramatic increase in terrorist attacks and so-called active-shooter incidents creates the potential for a great many additional lives to be saved by using TCCC concepts. Public awareness of such events has caused tremendous acceleration in the usual interchange of information between military and civilian trauma care experts via initiatives like the Hartford Consensus,55,81,82 the White House Stop the Bleed campaign,83 TCCC-based courses offered by NAEMT, and the development of the civilian Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC) program. These initiatives and many other local, state, and regional efforts have ensured that the advances in prehospital trauma care pioneered by TCCC, the JTS, and military medicine are being used to save lives in civilian trauma care practice with increasing frequency.84,86

Another of the earliest and most productive of the partnerships formed by TCCC with civilian medical organizations was that between TCCC and the Wilderness Medical Society (WMS). The wilderness environment is similar in some respects to the battlefield. In both settings, the patient and the care provider are often in remote locations where evacuation may be delayed and complicated, significant and ongoing hazard may be present during the time that care is being provided, the equipment available for treatment is very limited, the environments may be extreme, and those providing care are often not paramedics, emergency physicians, or trauma surgeons.87,88 The overlap in the austerities of the combat and the wilderness settings has resulted in collaboration between military and wilderness medicine experts in many areas. TCCC emphasizes the need to consider the specific tactical scenario in formulating a treatment plan for a casualty, and many combat trauma scenarios occur in wilderness areas. TCCC and the WMS conducted a workshop in which they developed guidelines for combat casualty care in wildernesssettings.89 Fentanyl lozenges recommended for analgesia in TCCC90 were previously recommended for use in wilderness trauma care in 1999.91 Hemostatic dressings and tourniquets used in TCCC are the mainstays for controlling life-threatening external hemorrhage in the wilderness.92,93 TCCC-based techniques are now used to train medical personnel who provide care to trauma victims in our country’s national parks.94 A 2-day TCCC preconference held at the 2016 annual meeting of the WMS resulted in a supplement to the WMS-sponsored journal Wilderness and Environmental Medicine dedicated to topics in TCCC.88

The endorsement of the ACS-COT of the TCCC-led use of prehospital tourniquets and hemostatic dressings has been discussed previously.55,78,81,82 The ACEP likewise endorsed tourniquets and hemostatic dressings for the control of life-threatening external hemorrhage in the prehospital setting.95

Additionally, the ACEP has endorsed some of the TCCC-led advances in prehospital analgesia. The survey of prehospital trauma care in Afghanistan in November 2012 led by Col. (retired) Russ Kotwal, Col. Stacy Shackelford, and Col. Erin Edgar, produced very valuable feedback from combat medical providers about the state of battlefield analgesia in U.S. forces.69 There was a clear and consistent message from medics, corpsmen, and PJs all over Afghanistan that they were happy with the analgesia options recommended by TCCC at the time, but that these options needed to be forged into a structured and coherent approach to battlefield analgesia. The JTS and the CoTCCC subsequently developed “Triple Option Analgesia.” This plan for battlefield analgesia provides faster, safer, and more effective relief of pain from combat injuries than the IM morphine that has been used by the U.S. Military since the Civil War.90 The Triple Option Analgesia plan incorporates the use of fentanyl lozenges pioneered by the 75th Ranger Regiment and the Army Special Missions Unit and ketamine pioneered by our colleagues in the United Kingdom and the U.S. Air Force PJ community. This plan customizes the analgesia choice to best suit the casualty’s level of pain and his or her physiologic status. The ACEP’s policy on out-of-hospital analgesia and sedation96 mirrors the Triple Option Analgesia plan. The agreement between these guidelines is compelling evidence that the Triple Option Analgesia plan is sound and that the lack of an FDA indication for fentanyl lozenges and ketamine as analgesics for acute pain does not preclude them from being best practice options based on available clinical evidence. This will be discussed more in the following section.

Summary and Take-Home Message

TCCC is different than civilian pre-hospital care. Battlefield considerations and conditions must be taken into account.

It is divided into 3 Phases (Care Under Fire, Tactical Field Care, and Tactical Evacuation Care).

Implementing the principles of TCCC has reduced preventable deaths on the battlefield.

References

1. Butler FK, Blackbourne LH. Battlefield trauma care then and now: a decade of tactical combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6)(Suppl 5):S395-402.doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3182754850.

2. Heiskell LE, Carmona RH. Tactical emergency medical services: an emerging subspecialty in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:778-785.

3. Bellamy RF. How shall we train for combat casualty care? Mil Med. 1987;152(12):617-621.

4. Baker MS. Advanced trauma life support: is it acceptable stand-alone training for military medicine? Mil Med.1994;159(9):581-590.

5. Butler FK, Hagmann J, Butler EG. Tactical combat casualty care in special operations. Mil Med. 1996;161(Suppl):1-16.

6. Maughon JS. An inquiry into the nature of wounds resulting in killed in action in Vietnam. Mil Med. 1970;135:8-13.

7. Butler FK. Military history of increasing survival: the US military experience with tourniquets and hemostatic dressings in the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts. Bull AmColl Surg. 2015 Sep;100(1 Suppl):60-64.

8. Butler FK. Two decades of saving lives on the battlefield: tactical combat casualty care turns 20. Mil Med.2017;182(3):e1563-e1568.

9. Butler FK. Tactical Combat Casualty Care: beginnings. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017 Jun;28(Suppl 2):S12-S17.

10. Richards TR. Commander, Naval Special Warfare Command letter. 1500 Ser 04/0341; 9 April 1997.

11. Butler FK, Holcomb JB, Giebner SD, McSwain NE, Bagian J. Tactical Combat Casualty Care 2007: evolving concepts and battlefield experience. Mil Med. 2007;172(Suppl):1-19.

12. Holcomb, JB. The 2004 Fitts lecture: current perspective on combat casualty care. J Trauma. 2005;59(4):990-1002.

13. Butler FK. Tactical medicine training for SEAL mission commanders. Mil Med. 2001;166(7):625-631.

14. DeLorenzo, RA. Medic for the millennium: the US Army91W healthcare specialist. Mil Med. 2001;166(8):685-688.

15. Pappas CG. The Ranger medic. Mil Med. 2001;166(5):394-400.

16. Allen RC, McAtee JM. Pararescue Medications and Procedures Manual. Hurlburt Field, FL: Air Force Special Operations Command; 1999.

17. Malish RG. The medical preparation of a special forces company for pilot recovery. Mil Med. 1999;164(12):881-884.

18. Krausz MM. Resuscitation strategies in the Israeli Army. Presentation to the Institute of Medicine Committee on Fluid Resuscitation for Combat Casualties, 17 September1998.

19. McDevitt I. Tactical Medicine. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press;2001.

20. McSwain NE, Frame S, Paturas JL, eds. Prehospital Trauma Life Support Manual. 4th ed. Akron, OH: Mosby; 1999.

21. Butler FK. Leadership lessons learned in tactical combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Jun;82(6Suppl 1):S16-S25.

22. Butler FK, Blackbourne LH, Gross KR. The combat medic aid bag: 2025. CoTCCC top ten recommended battlefield trauma care research, development, and evaluation priorities for 2015. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15(4):7-19.

23. Butler FK. Tactical combat casualty care: update 2009.J Trauma. 2010;69(Suppl):S10-S13.

24. Grissom CK, Weaver LK, Clemmer TP, Morris AH. Theoretical advantage of oxygen treatment for combat casualties during medical evacuation at high altitude. J Trauma.2006;61(2):461-467.

25. McSwain NE, Frame S, Salomone JP, eds. Prehospital Trauma Life Support Manual. 5th ed. Akron, OH: Mosby; 2003.

26. McSwain NE, Salomone JP, eds. Prehospital Trauma Life Support Manual, 6th ed. Akron, OH: Mosby; 2006.

27. Holcomb JB, McMullen NR, Pearse L, et al. Causes of death in special operations forces in the global war on terrorism:2001-2004. Ann Surg. 2007;245(6):986-991.

28. Kragh J, Walters T, Westmoreland T, et al. Tragedy into drama: an American history of tourniquet use in the current war. J Spec Oper Med. 2013;13:5-25.

29. Kragh JF, Walters TJ, Baer, DJ, et al. Survival with emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):1-7. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818842ba.

30. Kragh JF, Walters TJ, Baer DG, et al. Practical use of emergency tourniquets to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64(2)(Suppl):S38-S49. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31816086b1.

31. Caravalho J. OTSG Dismounted Complex Blast Injury Task Force: final report. 18 June 2011:44-47.

32. Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, et al. Death on the battlefield(2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6)(Suppl5):S431-S437.

33. Mabry R, McManus JG. Prehospital advances in the management of severe penetrating trauma. Crit Care Med.2008;36(7)(Suppl):S258-266.

34. Kelly JF, Ritenhour AE, McLaughlin DF, et al. Injury severity and causes of death from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom: 2003–2004 versus2006. J Trauma. 2008; 64(2)(Suppl):S21-S27. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318160b9fb.

35. Beekley AC, Sebesta JA, Blackbourne LH, Herbert GS,Kauvar DS, Baer DG, Walters TJ, Mullenix PS, HolcombJB. Prehospital tourniquet use in Operation Iraqi Freedom: effect on hemorrhage control and outcomes. J Trauma. 2008;64:S28-S37.

36. Tarpey M. Tactical combat casualty care in Operation Iraqi Freedom. US Army Med Dept J. 2005;April-June:38-41.

37. Butler FK, Holcomb JB. The tactical combat casualty care transition initiative. US Army Med Dept J. 2005;April-June:33-37.

38. Savage E, Forestier C, Withers N, Tien H, Pannel D. Tactical combat casualty care in the Canadian forces: lessons learned from the Afghan War. Can J Surg. 2011;59:S118-S123.

39. Tien HC, Jung V, Rizoli SB, Acharya SV, MacDonald JC. An evaluation of tactical combat casualty care interventions in a combat environment. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:174-178.

40. Butler FK, Holcomb JB, Giebner SD, McSwain NE, BagianJ. Tactical combat casualty care 2007: evolving concepts and battlefield experience. Mil Med. 2007;172(Suppl):1-19.

41. Gresham J. Giving back, again: Master Sgt. Luis Rodriguez and the tactical combat casualty care course. Faircount’s The Year in Veterans Affairs and Military Medicine.2006;2005-2006:136-139.

42. Bottoms M. Tactical combat casualty care: saving lives on the battlefield. Tip of the Spear (Command Publication of the US Special Operations Command). 2006;June:34-35.

43. Brown BD. Letter of Commendation to Army Medical Command. Commander, US Special Operations Command, 17August 2005.

44. Sohn VY, Miller JP, Koeller CA, et al. From the combat medic to the forward surgical team: the Madigan model for improving trauma readiness of brigade combat teams fighting the global war on terror. J Surg Res. 2007;138(1):25-31.

45. Holcomb JB, Stansbury LG, Champion HR, Wade C, Bellamy RF. Understanding combat casualty care statistics. J Trauma. 2006;60(2):397-401.

46. Eastridge BJ, Jenkins D, Flaherty S, Schiller H, Holcomb JB. Trauma system development in a theater of war: experiences from Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2006;61(6):1366-1372.

47. Beekley AC, Starnes BW, Sebesta JA. Lessons learned from modern military surgery. Surg Clin N Am. 2007;87(1):157-184.

48. Salomone JP. Letter to Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, 10 June 2008.

49. Hetzler MR, Ball JA. Thoughts on aid bags: part one. J SpecOper Med. 2008;8(3):47-53.

50. Pennardt A. TCCC in one special operations unit. Presentation at CoTCCC Meeting, 3 February 2009.

51. Kotwal RS, Montgomery HR, Kotwal BM, et al. Eliminating preventable death on the battlefield. Arch Surg.2011;146(12):1350-1358. doi:10.1001/archsurg.2011.213.

52. Butler FK, Smith DJ, Carmona RH. Implementing and preserving advances in combat casualty care from Iraq and Afghanistan throughout the US military. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Aug;79(2):321-326.

53. Mabry RL, DeLorenzo R. Challenges to improving combat casualty survival on the battlefield. Mil Med. 2014May;179(5):477-482.

54. Kotwal R, Montgomery H, Conklin C, et al. Leadership and a casualty response system for eliminating preventable death. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Jun;82(6 Suppl 1):S9-S15.

55. Jacobs LM and the Joint Committee to Create a National Policy to Enhance Survivability from Intentional Mass Shooting Events. The Hartford Consensus IV: a call for increased national resilience. Conn Med J. 2016;80:239-244.

56. Brown BD. Special operations combat medic critical task list. Commander, US Special Operations Command letter,9 March 2005.

57. Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (Navy Surgeon General)Message 111622Z: Tactical combat casualty care training, December 2006.

58. Holcomb, JB. The 2004 Fitts lecture: current perspective on combat casualty care. J Trauma. 2005;59(4):990-1002.

59. US Marine Corps Message 02004Z: Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) and Combat Lifesaver (CLS) fundamentals, philosophies, and guidance, August 2006.

60. US Coast Guard Message 221752Z: Tactical medical response program, November 2006.

61. Hostage GM. USSOCOM visit to the pararescue medical course at Kirtland AFB September 2005. Air Force Education and Training Command letter, 8 September 2005.

62. Kiley KC. Operational needs statement for medical simulation training centers for combat lifesavers and tactical combat casualty care training. Army Surgeon General letter DASG-ZA, 1 September 2005.

63. Blackbourne LH, Baer DG, Eastridge BJ, et al. Military medical revolution: military trauma system. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6)(Suppl 5):S388-S394. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31827548df.

64. All Army Activities Message 0902031521Z: Mandatory predeployment trauma training for Army medical department personnel, 3 February 2009.

65. Holcomb JB, Wilensky G. Tactical combat casualty care and minimizing preventable fatalities in combat. Defense Health Board memorandum, 6 August 2009. Military Health System website. https://health.mil/About-MHS/OASDHA/Defense-Health-Agency/Defense-Health-Board/Reports. Accessed March 21, 2018.

66. Casscells W. Tactical combat casualty care. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs memorandum, 4 March2009.

67. Woodson J. Tactical combat casualty care. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs Memorandum. 23 August2011.

68. Woodson J. Tactical combat casualty care for deploying personnel. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs Memorandum. 14 February 2014.

69. Kotwal RS, Butler FK, Edgar EP, Shackelford SA, Bennett DR, Bailey JA. Saving lives on the battlefield: a joint trauma system review of prehospital trauma care in combined joint operating area Y Afghanistan (CJOA-A) executive summary. J Spec Oper Med. 2013;13(1):77-80.

70. Sauer SW, Robinson JB, Smith MP, et al. Saving lives on the battlefield (part II): one year later: a joint theater trauma system & joint trauma system review of pre-hospital trauma care in combined joint operating area Y Afghanistan(CJOA-A). USCENTCOM Report. 2014.

71. Nathan ML. BUMEDINST 1510.25A Navy medicine tactical combat casualty care program. http://www.med.navy.mil/directives/ExternalDirectives/1510.25A.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2018.

72. Gross KR. Establishing a DoD standard for TCCC training: joint trauma system. White paper to the US Military Services Surgeons General. 11 September 2015. https://www.naemt.org/docs/default-source/education-documents/tccc/tccc-updates_092017/tccc-reference-materials/06-tccc-reference-documents/jts-white-paper-tccc-training-150910-v12.pdf?sfvrsn=884cd92_2. Accessed March 23, 2018.

73. Goforth C, Antico D. TCCC Standardization: the time is now. J Spec Oper Med. 2016;16:53-56.

74. Amor SP. ABCA Armies’ Program Chief of Staff letter. February 22, 2011.

75. Irizzary D. Training NATO special forces medical personnel: opportunities in technology-enabled training systems for skill acquisition and maintenance. J Special Ops Med.2013 Nov;(Suppl). doi:10.14339/STO-MP-HFM-224.

76. Holcomb J. Major scientific lessons learned in the trauma field over the last two decades. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002339.

77. McSwain NE, Frame S, Paturas JL, eds. Prehospital Trauma Life Support Manual. 4th ed. Akron, OH: Mosby; 1999.

78. Bulger E, Snyder D, Schoelles K, et al. An evidence-based prehospital guideline for external hemorrhage control: American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2014;18:163-173.

79. Stuke L, Pons P. Guy J, et al. Prehospital spine immobilization for penetrating trauma-review and recommendations from the prehospital trauma life support executive committee. J Trauma. 2011;71(3):763-769.

80. Butler FK, Carmona R. Tactical combat casualty care: from the battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq to the streets of America. The Tactical Edge. 2012;86-91. http://public.ntoa.org/default.asp?action=issue&year=2012&season=1%20-%20Winter&pub=Tactical%20Edge. Accessed March 22,2018.

81. Jacobs LM, Wade DS, McSwain NE, et al. The Hartford consensus: THREAT, a medical disaster preparedness concept. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(5):947-953.

82. Jacobs LM, McSwain NE Jr, Rotondo MF, et al. Improving survival from active shooter events: the Hartford Consensus. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Jun;74(6):1399-1400.

83. Levy M, Jacobs L. A call to action to develop programs for bystanders to control severe bleeding. JAMA Surg.2016;151(12):1103-1104.

84. Callaway D, Robertson J, Sztajnkrycer M. Law enforcement-applied tourniquets: a case series of life-saving interventions. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19:320-327.

85. Pons P, Jerome J, McMullen J, et al. The Hartford Consensus on active shooters: implementing the continuum of prehospital trauma response. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:878-885.

86. Callaway DW. Translating tactical combat casualty care lessons learned to the high-threat civilian setting: tactical emergency casualty care and the Hartford consensus. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017 Jun;28(2 Suppl):S140-S145.

87. Butler FK, Bennett B, Wedmore CI. Tactical combat casualty care and wilderness medicine: advancing trauma care in austere environments. Emerg Med Clin North Am.2017;35:391-407.

88. Bennett BL, Butler FK Jr, Wedmore IS. Tactical combat casualty care: transitioning battlefield lessons learned to other austere environments. Wilderness Environ Med.2017;28(2 Suppl):S3-S4.

89. Butler FK, Zafren K, eds. Tactical management of wilderness casualties in special operations. Wilderness Environ Med. 1998;9(2);62-117.

90. Butler FK, Kotwal RS, Buckenmaier CC III, et al. A triple-option analgesia plan for tactical combat casualty care. J Spec Operations Med. 2014;14:13-25.

91. Weiss E. Medical considerations for wilderness and adventure travelers. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83(4):885-902.

92. Drew B, Bennett B, Littlejohn L. Application of current hemorrhage control techniques for backcountry care: part one, tourniquets and hemorrhage control adjuncts. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:236-245.

93. Littlejohn L, Bennett B, Drew B. Application of current hemorrhage control techniques for backcountry care: part two, hemostatic dressings and other adjuncts. Wilderness Environ Med. 2015;26:246-254.

94. Smith WWR. Integration of tactical EMS in the National Park Service. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017;28(2Suppl):S146-S153.

95. American College of Emergency Physicians. Out-of-hospital severe hemorrhage control: policy statement. Ann Emerg Med. 2015 Dec;66(6):693.

96. American College of Emergency Physicians. Out-of-hospital use of analgesia and sedation. Ann Emerg Med. 2016Feb;67(2):305-306.

97. Department of Defense Instruction 1322.24: Military readiness training. Washington, DC: The Pentagon; 16March 2018.

98. Gross K. Establishing a DoD standard for TCCC training.US Army Institute of Surgical Research letter to the service Surgeons General and the Medical Officer of the Marine Corps, 11 September 2015. https://www.naemt.org/docs/default-source/education-documents/tccc/tccc-updates_092017/tccc-reference-materials/06-tccc-reference-documents/jts-white-paper-tccc-training---cover-ltradb7ab32fe31667a9799ff0000a338da.pdf?sfvrsn=ac86cd92_2. Accessed March 23, 2018.

99. Gurney J, Turner C, Burelison D, et al. Tactical combat casualty care training, knowledge and utilization in the Army. J Trauma. (publication pending).

100. Cousins R, Anderson S, Dehnisch F, et al. It’s time for EMS to administer ketamine analgesia. Prehosp Emerg Care.2017;21:408-410.

101. Butler FK, Holcomb JB, Kotwal RS, et al. Fluid resuscitation for hemorrhagic shock in tactical combat casualty care: TCCC guidelines proposed change 14-01. J Spec Oper Med. 2014;14:13-38.

102. Kotwal RS, Butler FK, Montgomery HR, et al. The tactical combat casualty care casualty card. J Spec Oper Med.2013;13:82-86.

Understanding Combat Casualty Care Statistics

John B. Holcomb, MD, Lynn G. Stansbury, MD, Howard R. Champion, FRCS, Charles Wade, PhD, and Ronald F. Bellamy, MD

The Journal of TRAUMA, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

J Trauma. 2006;60:397–401.

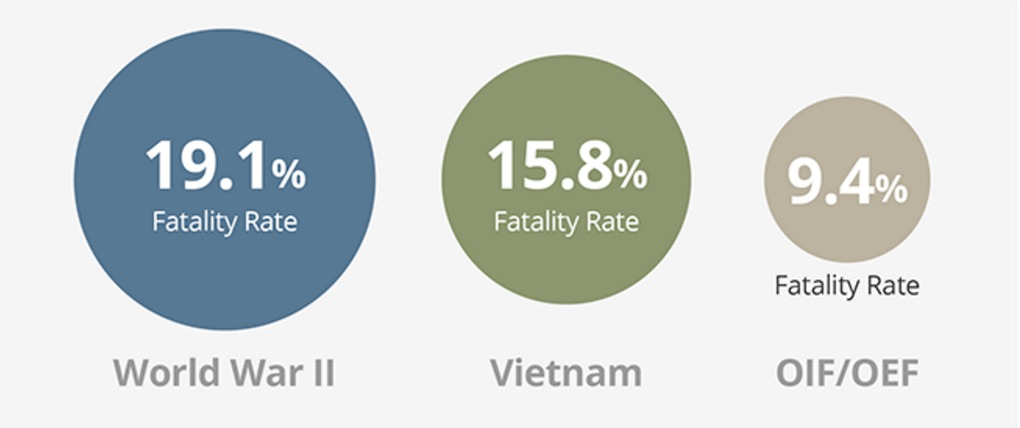

The objective of this paper was to develop standardized terminology and equations that produce the best insight into the effectiveness of care at different stages of treatment. These equations were then applied consistently across data from the WWII, Vietnam and the current Global War on Terrorism (OIF/OEF). Three essential terms were clarified:

- The Case Fatality Rate (CFR) as percentage of fatalities among all wounded

- Killed in Action (KIA) as percentage of immediate deaths among all seriously injured (not returning to duty)

- Died of Wounds (DOW) as percentage of deaths following admission to a medical treatment facility among all seriously injured (not returning to duty).

Using this clear set of definitions, the equations were used to ask two basic questions:

- What is the overall lethality of the battlefield?

- How effective is combat casualty care?

Take Home Message:

Based on a comparison of statistics for battle casualties from 1941-2005, the U.S. casualty survival rate in Iraq and Afghanistan has been the best in U.S. history.

Why Are We Doing Better?

Death on the Battlefield

Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): Implications for the future of combat casualty care

Brian J. Eastridge, MD, Robert L. Mabry, MD, Peter Seguin, MD, Joyce Cantrell, MD, Terrill Tops, MD, Paul Uribe, MD, Olga Mallett, Tamara Zubko, Lynne Oetjen-Gerdes, Todd E. Rasmussen, MD, Frank K. Butler, MD, Russell S. Kotwal, MD, John B. Holcomb, MD, Charles Wade, PhD, Howard Champion, MD, Mimi Lawnick, Leon Moores, MD, and Lorne H. Blackbourne, MD

The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery

J Trauma Acute Care Surg, Volume 73, Number 6, Supplement 5

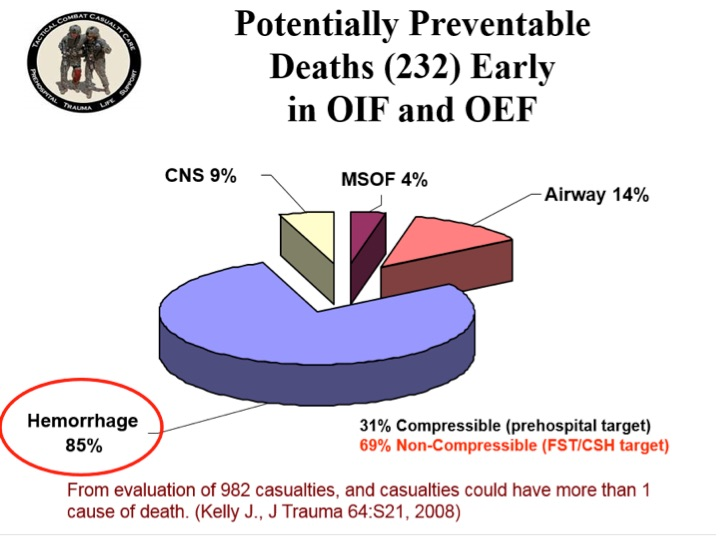

Most battlefield casualties died of their injuries before ever reaching a surgeon. As most pre-medical treatment facility (pre-MTF) deaths are nonsurvivable, mitigation strategies to impact outcomes in this population need to be directed toward injury prevention. To significantly impact the outcome of combat casualties with potentially survivable (PS) injury, strategies must be developed to mitigate hemorrhage and optimize airway management or reduce the time interval between the battlefield point of injury and surgical intervention.

Understanding battlefield mortality is a vital component of the military trauma system. Emphasis on this analysis should be placed on trauma system optimization, evidence-based improvements in Tactical Combat Casualty Care guidelines, data-driven research, and development to remediate gaps in care and relevant training and equipment enhancements that will increase the survivability of the fighting force.

READ FULL PDF

Take Home Message:

A Profile of Battlefield Injury

A Profile of Combat Injury

Howard R. Champion, FRCS(Edin), FACS, Ronald F. Bellamy, MD, FACS, COL, US Army, Ret., Colonel P. Roberts, MBE, QHS, MS, FRCS, L/RAMC, and Ari Leppaniemi, MD, PhD

The Journal of TRAUMA, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

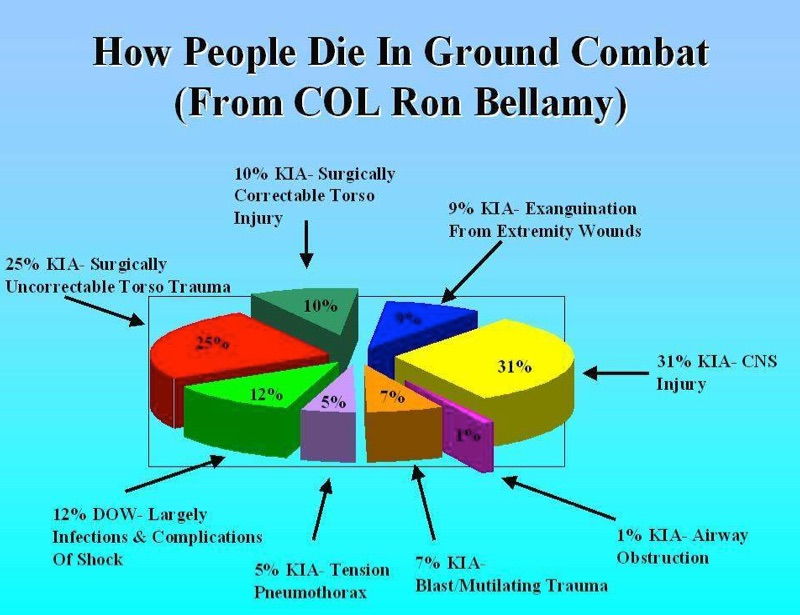

J Trauma. 2003;54:S13–S19.

Traumatic combat injuries differ from those encountered in the civilian setting in terms of epidemiology, mechanism of wounding, pathophysiologic trajectory after injury, and outcome. Except for a few notable exceptions, data sources for combat injuries have historically been inadequate. Although the pathophysiologic process of dying is the same (i.e., dominated by exsanguination and central nervous system injury) in both the civilian and military arenas, combat trauma has unique considerations with regard to acute resuscitation, including (1) the high energy and high lethality of wounding agents; (2) multiple causes of wounding; (3) preponderance of penetrating injury; (4) persistence of threat in tactical settings; (5) austere, resource-constrained environment; and (5) delayed access to definitive care. Recognition of these differences can help bring focus to resuscitation research for combat settings and can serve to foster greater civilian-military collaboration in both basic and transitional research.

Take Home Message:

Injury Severity and Causes of Death from OIF and OEF, 2003-04

Injury Severity and Causes of Death From Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom: 2003–2004 Versus 2006

Joseph F. Kelly, MD, Amber E. Ritenour, MD, Daniel F. McLaughlin, MD, Karen A. Bagg, MS, Amy N. Apodaca, MS, Craig T. Mallak, MD, Lisa Pearse, MD, Mary M. Lawnick, RN, BSN, Howard R. Champion, MD, Charles E. Wade, PhD, and COL John B. Holcomb, MC

The Journal of TRAUMA, Injury, Infection, and Critical Care

J Trauma. 2008;64:S21–S27.

The opinion that injuries sustained in Iraq and Afghanistan have increased in severity is widely held by clinicians who have deployed multiple times. To continuously improve combat casualty care, the Department of Defense has enacted numerous evidence-based policies and clinical practice guidelines. Overall causes of death were examined, looking for opportunities of improvement for research and training.

In the time periods of the war studied, deaths per month has doubled, with increases in both injury severity and number of wounds per casualty. Truncal hemorrhage is the leading cause of potentially survivable deaths. Arguably, the success of the medical improvements during this war has served to maintain the lowest case fatality rate on record.