Drowning Management

Joint Trauma System

SUMMARY OF CHANGES

1. Updates provided as the World Health Assembly adopted its first drowning resolution in 2023 with current estimate of over 90% of drowning related deaths are preventable. Updated epidemiology provided.

2. Clarification on automated external defibrillator (AED) use provided. AEDs do have a limited role in the care of drowning patients; however, the application of these devices should not interfere with compressions and ventilation as shockable rhythms are present in less than 6% of patients.

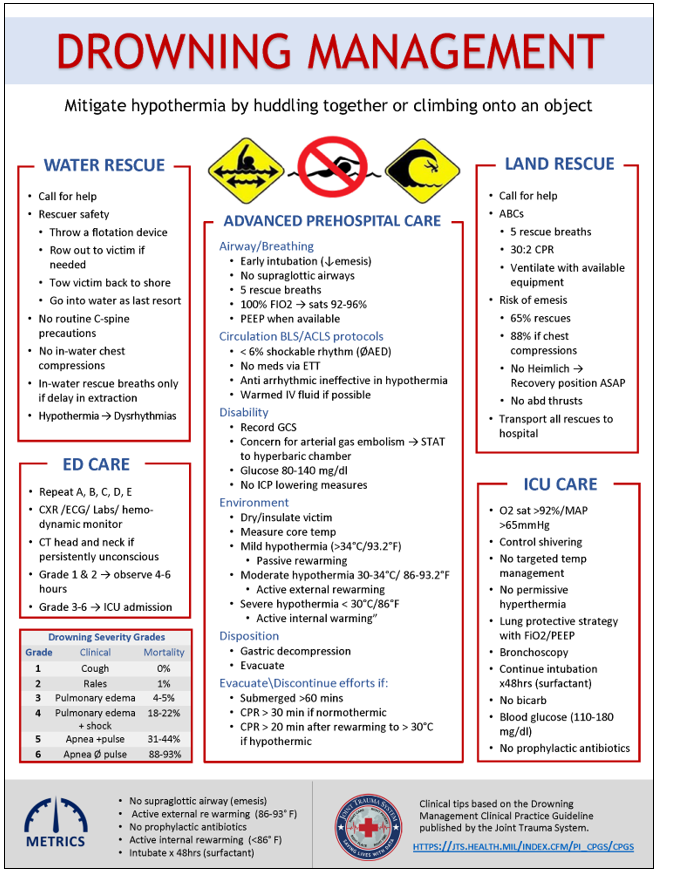

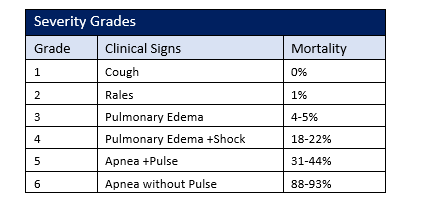

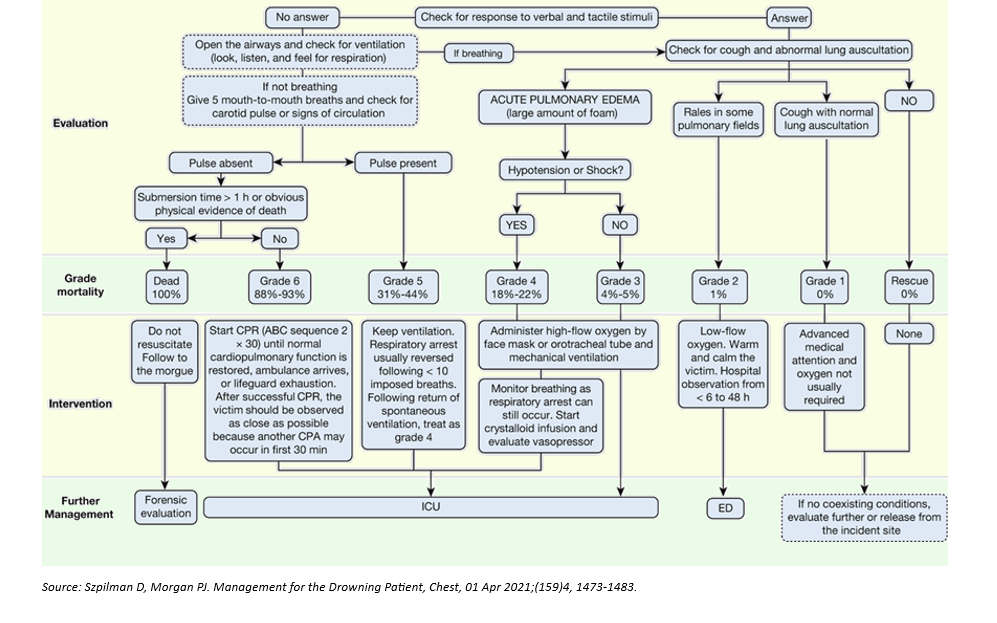

3. Updated ER disposition recommendations based on grade of severity and mortality with associated flow chart (Figure 1). Grades 2 and below may be safely observed and likely discharged within 4-6 hours.

4. Expanded ICU management recommendations.

- Recommendation for active physiologic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) titration with maintenance for 48 hours prior to initiation of liberation trials.

- Current lung protection ventilation strategy updated. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) neither recommended for, nor against.

- Metabolic derangements discussed – no evidence-based data for the routine use of bicarbonate for correction of these derangements.

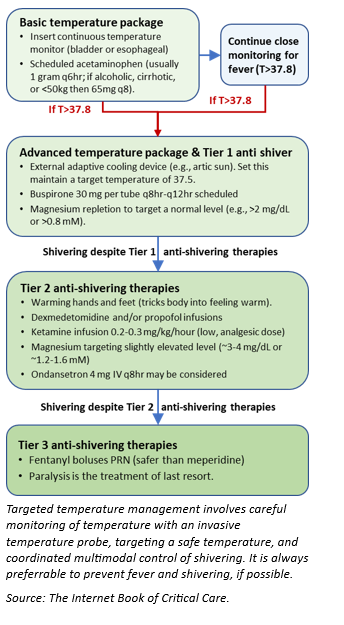

5. Recommendation for aggressive fever prevention (for neuroprotection) but no recommendation for traditional targeted temperature management in the post-cardiac arrest patient per the recent Targeted Temperature Management 2 trial.

6. Recommendations for the management of shivering.

7. No role for the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics.

8. Updated Swimming Induced Pulmonary Edema (SIPE).

9. Risk factors: Cold water, pre-existing (Cardiovascular) CV disease, overhydration, horizontal positioning during swimming, tight fitting wetsuits, and concurrent respiratory infections.

10. Diagnostic findings typical chest x-ray findings of perifissural and interstitial thickening, widened azygos vein diameter, and enlarged cardiac silhouette.

11. Management: ß2-agonists, Positive Pressure, Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) Device.

INTRODUCTION

While various necessary military occupations put service members at increased risk for drowning, particularly those serving in the Navy and Marine Corps, this risk is mitigated through methodical training and operational risk management processes. However, drowning events in combat and operational environments can occur and are highly influenced by the tactical environment. In civilians, drowning is thought to be preventable in over 90% of cases.1-2 As a result of the significant human, social, and economic tolls of drowning, the World Health Assembly adopted their first resolution regarding drowning prevention in 2023.3 The purpose of this clinical practice guideline provides an overview of drowning and associated conditions based on the best available current medical evidence. It should be used as a standardized framework to guide first responders, prehospital emergency medical service personnel, and medical department personnel in evaluating, diagnosing, and managing common in-water emergencies. Caregivers supporting operations with an increased risk of drowning should review this CPG with the entire medical team including first responders.

MILITARY OCCUPATIONS WITH DROWNING RISK AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Various military occupations involve significant water exposure and carry a risk of drowning. These include but are not limited to naval operations at sea, military special operations, combat swimmers, divers, and amphibious assault units. Each unit has risk management measures in place to mitigate the risk of drowning events and subsequently provide immediate aid.

Between 2013 and 2017, 359 recreational and line of duty drowning cases were identified amongst active-duty service members. Generally, members of the Marine Corps are at highest risk as well as members working within motor transport occupations. Off duty alcohol related incidents and alcohol use disorder continue to play a significant factor in drowning risk.2,4

Combat related drowning incidents have been associated with a mortality as high as 37.5% and are often related to vehicle roll overs. One 2-year epidemiology study found that combat related drowning represents 3% of all combat deaths.5-6

Man-overboard events aboard naval vessels at sea are uncommon occurrences but are associated with a high mortality when they occur. Between 1970 and 2020 there were 220 man-overboard events on U.S. Naval subsurface and surface vessels involving 352 casualties with an associated 72% mortality.7

Naval vessel collisions at sea impacting the integrity of the ship’s hull can result in highly lethal drowning events. The 2017 USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain collisions with separate large civilian commercial ships both resulted in significant hull breaches below the waterline. In the two events, there were 85 reported casualties from the combined warship crews, 20% (17) died from drowning.

The epidemiology of drowning incidents during amphibious vehicle training is unknown, but they do occur. In 2020 an Amphibious Assault Vehicle (AAV) carrying 15 Marines and 1 Sailor took on water and sunk during a training exercise. Ultimately 8 Marines and 1 Sailor died from drowning. One severely injured Marine required ongoing critical care and respiratory support.8

CIVILIAN EPIDEMIOLOGY OF DROWNING

Reported incidence of 360,000 to over 500,000 civilian deaths attributed to unintentional drowning annually, not including boating accidents or those related to natural disasters. *These numbers are thought to be underreported. 2, 9-10

Worldwide, children ages 1-4 have the highest rates of drowning, followed by children ages 5-9. Boys are twice as likely to die from drowning.3

It is the leading cause of death or contributing factor among scuba divers (100-150/year). Primary etiology of death can be difficult to determine as distinction between equipment malfunction or medical emergency can be challenging.10-12

Drowning occurs when water fills the airways for any reason. It is important to note that progressive aspiration of water can result in hypoxemia. If loss of consciousness occurs, the continued hypoxemia can result in bradycardia and cardiac arrest. In the lungs, aspiration can cause a washout and destruction of alveolar surfactant resulting in severe hypoxia, alveoli derecruitment, reduced pulmonary compliance and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, all of which can complicate ventilator management. It should also be noted that there is no such thing as “Near Drowning.” Correct terminology includes “Non-Fatal Drowning” and “Fatal Drowning.”

Immersion in water when associated with panic, exhaustion, inadequate water competency, a medical emergency such as lethal cardiac dysrhythmia or seizure, or effects of hypo/hyperthermia can lead to drowning from one of the following mechanisms:10-15

- Airway below the water’s surface → breath hold breakpoint (inability to resist urge to breathe due to hypercapnia and hypoxemia) → progressive aspiration and subsequent hypoxemia (see below) → loss of consciousness (LOC) → apnea and passive airway flooding → bradycardia → cardiac arrest.1

- Aspiration (either sea water or fresh water) causes a degree of surfactant washout/destruction increased alveolar surface tension and diminished integrity of the alveolar-capillary membrane atelectasis/ derecruitment and disruption of the alveolar capillary membrane → unregulated fluid shifts resulting in noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, reduced pulmonary compliance ( ~10-40% with as little as 1-3cc/kg water) → right to left shunting resulting in hypoxemia.1

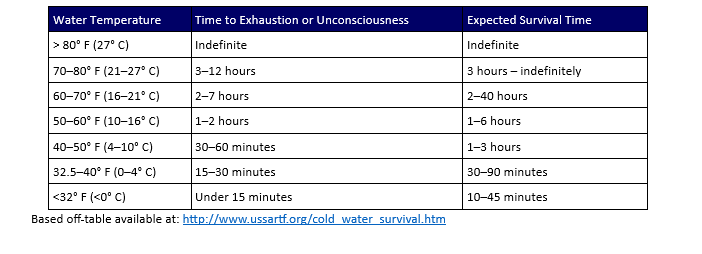

- Cold water submersion → inadvertent gasp for air (“cold shock response”) → tachypnea, vasoconstriction, tachycardia from sympathetic surge → arrhythmias (especially in patients with long QT syndrome) or parasympathetic mediated bradycardia (“diving response”), altered mental status, diminished strength, and coordination.1 Table 1 shows expected survival times in cold water.

In the civilian and military environment, one of the most important principles in drowning management is to first prevent drowning. Examples of prevention and operational risk management in high-risk military occupations include:

- Sailors assigned to naval vessel are indoctrinated in the principles of universal damage control, which among other tenets includes techniques to control (e.g., shoring materials, secure hatches) or remove flooding water (e.g., pumps) when the hull is breeched. Hull integrity is typically controlled with shoring materials such as mattresses, pillows, canvas materials, hydraulic jacks and wooden wedges, beams, plugs or blocks.

- Amphibious operations are a particularly high-risk activity as evidenced by a recent 2020 amphibious assault vehicle tragedy during a training event. Of issues that led to the nine drowning deaths, failure to apply appropriate operational safety protocols contributed, highlighting the importance of prevention.8 With this risk, all personnel assigned to these platforms are required to complete both intermediate level swim qualifications and submersible vehicle egress training. All personnel have received some degree of Tactical Combat Casualty Care training in order to provide buddy aid in the event of an emergency. Training evolutions require the presence of Marine Corps Instructors of Water Survival who are trained for in-water rescue.

- Implementation of risk management measures during dive and other high-risk water operational and training evolutions is critical in prevention of drowning. These measures include pre-evolution safety briefs, trained standby and safety divers, swim buddies, on scene medical providers, water rescue crafts on site, wearing personal flotation devices, drilling man-overboard procedures, and use of light sticks for night training.

- Careful consideration must be given to the potential risks of conducting open sea operations in extreme environmental conditions such as rough sea state or heavy swell. In these extreme conditions, operations or training should be altered (when possible) to mitigate the risk of drowning and other mishaps.

- Divers should undergo thorough review of dive plan prior to scheduled dives to include anticipated depth/time profile ensuring adequate air supply in addition to routine pre-dive equipment safety checks.

INITIAL RESUSCITATION

- Call for help and encourage patient to move away from danger.16-17

- Place the patient so that the head and feet are at the same level. If rescuing a patient from the shoreline, place them parallel to the shoreline.

- Airway, Breathing, Circulation. If unconscious and not breathing, begin with 5 rescue breaths, then continue with traditional basic life support utilizing a ratio of 30 compressions and 2 rescue breaths. Five breaths are used initially as a recruitment maneuver. Drowning patients without circulatory arrest will often respond to rescue breaths alone.10

- Ventilation support with available tools (oxygen, bag valve mask (BVM), etc.).

- Rescue breaths and CPR represent significant risk of emesis in drowning victims (65% of those requiring rescue and 88% of those receiving chest compressions).10 Placing patients in the recovery position as able can reduce the risk of subsequent aspiration.

- Prepare for transportation to a higher echelon of care. All victims of drowning who require resuscitation (including rescue breathing alone) should be transported to the hospital for evaluation and monitoring, even those who are alert and demonstrate hemodynamic and respiratory stability at the scene of initial injury.

ADVANCED PREHOSPITAL CARE

Patients requiring continued resuscitation or those with concern for hypothermia may require more advanced prehospital care which cannot be delivered by typical bystanders such as definitive airway management, supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilatory support, gastric decompression, or thermal insulation.11,15 Aggressive resuscitation attempts should be initiated unless clear signs of death or as limited by operational requirements. Patients have survived prolonged submersion historically, especially in the hypothermic environment.13 For this level of care, use the typical ABCDE format below.

- Assess patency of the patient's airway; consider foreign bodies unique to drowning injuries such as sand or seaweed and perform finger sweep if there is a visible obstruction.

- If the patient is unconscious and unable to maintain their own airway, place the patient in the recovery position (lateral recumbent) to minimize risk of aspiration. 10-11

- In the obtunded patient, consider early intubation if an expert in airway management is available. Definitive airway is required in patients with respiratory arrest as soon as feasible. Continued use of BVM will increase risk of emesis. If a unit is trained for the capability, intubation will decrease risk of aspiration if it is available in the pre-hospital environment.

- Due to concern for increased pulmonary airway pressures required for ventilation of the drowning patient, the use of supraglottic airways (e.g., laryngeal mask airways) is discouraged and maintaining a seal may be ineffective.10

- Immediately perform five rescue breaths in a patient who remains unconscious and in respiratory arrest.10,18

- If the patient is breathing spontaneously, immediately apply O2 at 15 liters/min by nonrebreather as soon as possible and until discontinued by medical officer.10-11

- Consider early use of positive pressure to maintain PEEP. Aspiration can reduce surfactant and increase atelectasis.

- Avoid head down positioning or abdominal thrusts as they decrease ventilation and increase risk of vomiting, which can lead to aspiration. Heimlich maneuver is NO LONGER recommended for drowning.16,19

- Goal oxygen saturation is 92-96%: Place pulse oximeter on ear lobe or forehead for more accurate readings.20,21

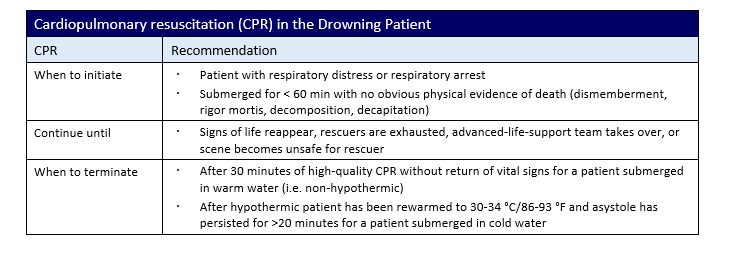

- While pulses may be difficult to identify due to hypothermia or hypotension, absence of a pulse necessitates initiation of Basic Life Support/Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) protocols. See Table 2 for CPR guidance in the drowning patient.

- Most common dysrhythmias are asystole and pulseless electrical activity. Defibrillation is not indicated with these rhythms. Attempts to attach an AED should not be made if it delays or interferes with compressions and ventilation.10,11,13

- Shockable rhythms (ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia) are present in <6% of patients and have a more positive prognosis.1

- Obtain IV access when able. Intraosseous access is an acceptable alternative if unable to obtain IV access. Administering ACLS medications through the endotracheal tube is discouraged in the drowning patient.10,11

- Many drowning patients will be volume depleted intravascularly and will have volume responsive hemodynamics. In patients who are mechanically ventilated or receiving positive pressure, hypotension may be more common as increased intrathoracic pressure reduces central venous return/preload. IV crystalloid should be considered if available. In the hypothermic patients, warmed IV fluids at 43°C (109°F) should be considered.16

- Use of IV fluids must be judicious given the increased risk for noncardiogenic pulmonary edema in these patients.

- Notably, many ACLS interventions, including pacing, atropine, lidocaine, and defibrillation, are ineffective with low core body temperatures. Antiarrhythmics should be withheld for core temperatures of < 30 °C (86 °F).

- Emphasis should be placed on chest compressions and ventilations to maintain perfusion.18

- Initial determination of Glasgow Coma Score should be completed to guide additional resuscitative efforts.

- If circumstances surrounding the drowning are unwitnessed and loss of consciousness is persistent, consider other etiologies other than hypoxemia, such as head injury, intoxication, arterial gas embolism (AGE). This will depend on circumstances surrounding the event (e.g., scuba diver surfacing unconscious or with neuro complaint).12

- If AGE is suspected, begin notification of hyperbaric chamber team (See Appendix B).

- The following have not shown benefit in the unconscious drowning patient: hyperosmolar agents (e.g., mannitol or hypertonic saline), hyperventilation, barbiturate coma, intracranial pressure monitoring.

- Glucose – maintain between 80-140 mg/dL for ventilated patients.

ENVIRONMENT (HYPOTHERMIA MANAGEMENT)

- Keep the victim warm (use core temperature instead of infrared devices - a low range refrigerator thermometer may be necessary). Stabilize body temperature - dry and insulate the patient to prevent heat loss.11,21-22

- Mild hypothermia: 34-35°C (93.2-95°F): passive rewarming (i.e. warm blankets and environment).

- Moderate hypothermia: 30-34°C (86-93.2°F): active external rewarming will be required when available (i.e. heating blankets, radiant heat, forced hot air, warmed IV fluids at 43°C (109°F), warm water packs).

- Severe hypothermia: < 30°C (86°F): active internal rewarming will be required when available (peritoneal lavage, esophageal rewarming tubes, cardiopulmonary bypass, extracorporeal circulation); consider extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Withhold ACLS medications until temperature >30°C (86°F).16

- Gastric decompression: Consider placement of an orogastric or nasogastric tube in the stabilized, intubated patient given the increased risk of emesis from resuscitative efforts.

- Evacuation: Evacuate if victim required resuscitation, was unresponsive in the water, or has dyspnea or other respiratory symptoms.

- Continue resuscitation and transport to higher level of care unless there are obvious signs of death.

TERMINATING RESUSCITATION EFFORTS11,19

- If the victim has been submerged for greater than 60 minutes, in-water rescue should transition to body recovery.

- In the non-hypothermic patient, resuscitation may be stopped after 30 minutes of CPR without return of spontaneous circulation.

- In the hypothermic patient, continue resuscitation until patient is rewarmed to 30-34 °C/86-93 °F, then continue CPR. Efforts may be discontinued if the patient remains asystolic for greater than 20 minutes. Lowest known documented initial temperature in patient with full neurologic recovery was 56.6°F/13.7 °C.

- Duration of submersion correlates with risk of death or severe neurologic impairment as noted:10

- 0-5 min – 10%

- 6-10 min – 56%

- 11-25 min – 88%

- >25 min – nearly 100%

ED/ICU CARE

INITIAL ER ASSESSMENT AND INTERVENTIONS

Upon arrival to the Emergency Room (ER), rapidly evaluate the patient and rule out traumatic injury. Perform primary (ABCDE) and secondary assessment with specific focus on the following: secure airway, provide adequate oxygenation, ensure hemodynamic stability, gastric decompression, thermal insulation, and identifying concomitant traumatic injury. 10,11,19,22 Following initial ER resuscitation, specific systems-based interventions may be applied as noted in the ICU Management section. Additional immediate interventions below (does not substitute for ER standards of care):

- Chest X-Ray – regardless of patient’s clinical appearance. Used to establish a baseline.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG)

- Volume resuscitation as appropriate for hemodynamic support. Urinary catheter placement. Invasive monitoring (e.g., arterial line) and central access at the discretion of the treating physician.

- CT head and neck is recommended in the persistently unconscious patient to look for evidence of traumatic injury.

- It is important to note, that in the military setting, particularly during combat or other high risk military operations to look for and rule out traumatic injury and hemorrhage in patients with suspected drowning and hypotension. At a minimum an ultrasound FAST (Focused Assessment Sonography for Trauma) should be performed in all drowning victims without evidence of trauma. In unconscious patients, in addition to a CT head and neck, perform a pelvic X-ray as pelvic fracture can be a significant source of bleeding. In drowning victims with persistent hypotension without evidence of trauma, CT torso (chest, abdomen, and pelvis) should be performed to rule out solid organ injury, retroperitoneal bleeding or other occult traumatic injury.

- Arterial/venous blood gas

- Complete blood count

- Comprehensive metabolic panel

- Glucose

- Troponin I

- Prothrombin time/ partial thromboplastin time

- Urinalysis

- Creatine Kinase

- Urine myoglobin

- Urine drug screen

- Blood alcohol

Once the patient is stabilized from a respiratory and hemodynamic standpoint, disposition should be determined. Figure 1 below helps to establish guidelines for ICU admission versus observation and safe discharge based drowning mortality risk and drowning grade (Table 3).

Patients with a Grade 2 or lower may safely be observed either in the ER or non-intensive care inpatient observation for 4-6 hours.1

- Patients are responsive to verbal and tactile stimuli (GCS >13).

- May have cough or rales on pulmonary evaluation.

- Able to maintain oxygenation with low-flow oxygen (typically 2L by nasal canula).

Patients with Grades 3-6 should be admitted to the ICU.1

- Unresponsive patients

- Patients with significant pulmonary edema or respiratory failure

- Patients in shock (hypotension or poor perfusion shown by capillary refill, elevated lactate, organ failure)

Appropriate consults should be made at this time and may include critical care (medical and neurological), cardiology, psychology.

ICU MANAGEMENT

NEUROLOGIC

The majority of long term sequalae of drowning events are secondary to neurologic injury. Early efforts should be made to improve central nervous system oxygen delivery while providing evidence-based neuroprotection in the post-resuscitative period.

- Maintain adequate oxygenation of SaO2 >92%. *In the intubated post arrest patient, hyperoxia (PaO2 >300mmHg) is associated with poor neurologic outcomes.41 Consider placement of an arterial line to monitor PaO2.

- Maintain systemic mean arterial pressure > 65mmHg to ensure adequate cerebral perfusion (cerebral perfusion pressure = mean arterial pressure – intracranial pressure). Low dose vasopressor support may be necessary. As discussed above, in military drowning patients with an abnormal neurologic exam and persistent hypotension, ICU caregivers must rule out traumatic injury and hemorrhage as a cause of hypotension. * There is no evidence to support invasive intracranial pressure monitoring or supranormal cerebral perfusion pressures.23

- Maintain head of bed at 30 degrees with head midline.

- Only aggressive fever prevention is recommended. Cooling with targeted temperature management is NOT recommended.24

In patients who are still rewarming, aggressive shivering control should be implemented (See Figure 2 on right for an example of shivering management protocol). Significant adverse effects from prolonged shivering include lactic acidosis, elevated intracranial pressure, rhabdomyolysis, discomfort, and interference with monitoring devices.24

Aspiration of both seawater and freshwater in relatively small quantities can lead to disruptions in the surfactant equilibrium of the lungs. Reduced surfactant leads to atelectasis which can make patients more prone to atelectrauma and subsequent biotrauma (neutrophil migration and subsequent acute respiratory distress syndrome or sepsis).36,38 Osmotic shifts in the alveoli can lead to noncardiogenic pulmonary edema which results in reduced compliance, right to left shunting, and hypoxemia. Evidence-based care for mechanically ventilated patients should be followed. 2

- Maintain saturation at 92% (or PaO2 between 55-80mmhg) while avoiding hyperoxia.

- Oxygenation should be maintained by titrating fraction of inspired O2 (FIO2) and incremental increases in PEEP, which will help to reduce incidence of barotrauma. Current literature suggests achieving a PaO2>FIO2 ratio of >250.

- Once adequate oxygenation has been achieved, the same PEEP should be maintained for 48 hours without attempts to wean from the ventilator.

- The best available evidence indicates pulmonary surfactant restores in 48 hours. Early attempts at extubation may lead to recurrent pulmonary edema and increased ventilator days.

- Avoid permissive hypercapnia (unless neurologic status is intact) due to concern for concomitant neurologic injury that may worsen with high pCO2.

- A lung protective ventilator strategy should be followed with the goal of preventing barotrauma.

- Maintain tidal volumes of 6cc/kg of predicted body weight.

- PEEP strategy as noted above.

- Maintain plateau pressures < 30 cmH20, Driving pressure <15 cmH20.

- Consider bronchoscopy for quantitative cultures and foreign body removal if there is concern for aspiration (e.g., sand, seaweed).

- Patients with prolonged, severe, or refractory hypoxemia should be considered for ECMO; however, drowning patients were not specifically included in landmark ECMO trials (e.g., EOLIA, CESAR). Case reports of ECMO use in profoundly hypothermic patients have demonstrated some success.

- No role for artificial surfactant.

Low output heart failure and lethal dysrhythmias are common in drowning victims. While hypoxemia is the primary driver of these conditions, correction of hypoxemia may not immediately restore normal cardiac function and ICU physicians should be prepared to manage these issues. Reduced cardiac output may lead to cardiogenic component of pulmonary edema or worsen additional organ failure (e.g., cardiorenal syndrome).1

- Consider echocardiogram initially. In patients requiring inotropic support, consider cardiac output monitoring through either noninvasive cardiac output monitoring, pulse contour analysis, or pulmonary artery catheter.

- Maintain MAP goal of >65mmHg. Stroke volume variation can be utilized to identify patients that may be volume responsive and should be given additional crystalloid resuscitation. Judicious fluid resuscitation should be maintained.

- Patients who are not volume responsive and remain hypotensive should receive vasopressor support. Again, be sure to rule out traumatic injury and hemorrhage as a cause of hypotension.

- Patients should remain on continuous telemetry to assess for dysrhythmias.

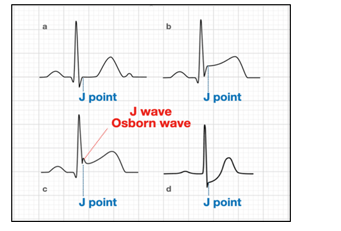

- EKG or telemetry may demonstrate the presence of Osborne waves or J Waves (extra deflection at the end of the QRS complex) in the hypothermic patient. See Figure 3 below.

HEMATOLOGIC, ENDOCRINE, AND RENAL

Drowning victims requiring the ICU are critically ill and can be prone to the same hematologic, metabolic, and renal pathologies as other ICU patients. There is no evidence that there is clinically significant hemolysis or electrolyte shifts in drowning patients. Rates of renal failure secondary to decreased perfusion during resuscitative efforts or subsequent decreased cardiac output are similar to other cardiac arrest patients.

- No role for routine use of bicarbonate in patients with metabolic acidosis.10

- Maintain euglycemia (140-180mg/dl).25

- Renal failure in the majority of drowning patients is uncommon; however, when present, it may be secondary to decreased perfusion, myoglobinuria or hemoglobinuria.10

There is no role for prophylactic antibiotics in drowning victims either in freshwater or saltwater. Furthermore, rates of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria obtained from seawater drowning victims is negligible and broad-spectrum coverage is not indicated.

- Broad spectrum antibiotics to cover both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria are indicated in patients where drowning occurs in a source with a high pathogen load (UFC >10).20

- Monitor patient for signs and symptoms of pneumonia (new pulmonary infiltrates on imaging, leukocytosis, fever, worsened respiratory status).

- Routine cultures are not required unless specific concern is present.

- Consider bronchoscopy for quantitative cultures or source control of possible aspirated nidus of infection.

SWIMMING INDUCED PULMONARY EDEMA (SIPE)

Most commonly presents in individuals conducting sustained strenuous surface swimming in cold water (e.g., Marine combat swimmers, special operators, scuba divers, and triathletes).26,27 Studies have shown a variable incidence of SIPE among different populations. Symptom severity can range from full recovery within 24 hours to death.28-33 While severe outcomes are possible, most otherwise healthy individuals will recover within 24-48 hours. Recurrence of SIPE is not uncommon.34

RISK FACTORS

- Pre-existing cardiovascular disease

- Female sex

- Prior history of SIPE

- Overhydration

- Prone horizontal position during swimming

- Tight-fitting wetsuits

- Concurrent respiratory infection.35-40

During or immediately after exertional water immersion/swimming:

- Dyspnea or cough

- Hypoxemia

- +/- Frank hemoptysis or expectoration of pink-frothy sputum

- Findings on chest radiograph suggestive of pulmonary edema. These include air space opacification, perifissural thickening, increased septal and interstitial lines, widened azygos vein diameter, and enlarged cardiac silhouette. Findings typically resolve within 48 hours.36

- The presence of B-line artifacts on ultrasound may assist in the diagnosis of SIPE when chest x-ray capabilities are unavailable. 37

- Pulmonary infection or water aspiration is considered less likely to be the underlying causes of clinical presentation.

Incompletely understood and thought to be due to:

- Peripheral vasoconstriction in the setting of exertional water immersion leads to shunting of blood from the periphery to the central venous system. This engorges central veins and leads to an increase in cardiac preload and pulmonary artery pressures. Increased pressure in the pulmonary vessels results in ‘fracturing’ of pulmonary capillaries that lead to interstitial and alveolar edema.

- Diastolic dysfunction and stroke volume mismatch between the left and right ventricles may contribute to SIPE pathophysiology. 38

- Typically, self-limiting and resolves with rest within 24-48 hours.39

- Diuretics, → , ß 2-agonists, and supplemental oxygen may be given for persistent SIPE-related symptoms or severe cases of SIPE.40

- CPAP and PEP device have proved feasible and safe for pre-hospital treatment of SIPE. 39

PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT (PI) MONITORING

POPULATION OF INTEREST

Drowning casualties

INTENT (EXPECTED OUTCOMES)

- Transport all drowning victims requiring rescue breathing or resuscitation to the hospital for evaluation and monitoring.

- Intubate obtunded drowning victims early and avoid supraglottic airways.

- Avoid maneuvers that increase risk of emesis (e.g.., Heimlich, head-down, abdominal thrusts).

- Withhold antiarrhythmic medications in severe hypothermia with core temps < 30 °C (86 °F).

- Alert hyperbaric chamber teams in cases of suspected arterial gas embolism.

- Avoid osmotic diuresis, barbiturate coma, hyperventilation, and ICP monitoring.

- Institute active external rewarming for moderate hypothermia and active internal rewarming for severe hypothermia.

- Avoid shivering during rewarming measures. (See Figure 2.)

- Avoid hyperoxia and use lung protective strategies in the critical care setting.

- Delay weaning from mechanical ventilation for the first 48 hours to avoid recurrent pulmonary edema from insufficient pulmonary surfactant.

- Avoid antibiotic prophylaxis except in cases with submersion in water with known high pathogen load.

- Avoid targeted temperature management as a neuroprotective strategy.

PERFORMANCE/ADHERENCE MEASURES

- Number and percentage of drowning victims with documentation of pre-hospital airway management (e.g. NPA or definitive airway)

- Number and percentage of drowning victims with temperatures 30-34°C (86-93.2°F) rewarmed with active external measures.

- Number and percentage of drowning victims with temperatures < 30 °C (86 °F) rewarmed with active internal measures.

- Number and percentage of drowning victims receiving prophylactic antibiotics in the first 24 hours.

- Number and percentage of drowning victims that remain intubated for the first 48 hours.

DATA SOURCE

- Patient Record

- Department of Defense Trauma Registry

SYSTEM REPORTING & FREQUENCY

- The above constitutes the minimum criteria for PI monitoring of this CPG. System reporting will be performed annually; additional PI monitoring and system reporting may be performed as needed.

- The system review and data analysis will be performed by the JTS Chief and JTS PI Branch.

- The Ustein Uniform Reporting Data form for Drowning will be used.

RESPONSIBILITIES

It is expected that medical department personnel, particularly of the sea services (U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Coast Guard, and U.S. Merchant Marine) will become familiar with these clinical practice guidelines and incorporate them into both operational planning and emergency medical response plans.

REFERENCES

- Szpilman D, Morgan PJ. Management for the drowning patient. Chest. 2021 Apr;159(4):1473-1483.

- Bell NS, Amoroso PJ, Yore MM, Senier L, Williams JO, Smith GS, Theriault A. Alcohol and other risk factors for drowning among male active-duty U.S. Army soldiers. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2001 Dec;72(12):1086-95.

- World Drowning Prevention Day 2023.

- Williams VF, Oh GT, Stahlman S. Update: Accidental drownings and near drownings, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2013-2017. MSMR. 2018 Sep;25(9):15-19. PMID: 30272989.

- Allan PF, Fang R, Martin KD, Glenn M, Conger NG. Combat-associated drowning. J Trauma. 2010 Jul;69 Suppl 1:S179-87.

- Hammett M, Watts D, Hooper T, Pearse L, Naito N. Drowning deaths of U.S. Service personnel associated with motor vehicle accidents occurring in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, 2003-2005. Mil Med. 2007 Aug;172(8):875-8.

- Benham DA, Vasquez MC, Kerns J, Checchi KD, Mullinax R, Edson TD, Tadlock MD. Injury trends aboard US Navy vessels: A 50-year analysis of mishaps at sea. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023 Aug 1;95(2S Suppl 1):S41-S49.

- Marine Corps Investigation into 2020 Amphibious Assault Vehicle Sinking - USNI News, Mar 26, 2021.

- Schmidt AC, Sempsrott JR, Hawkins SC, Arastu AS, Cushing TA, Auerbach PS. Wilderness medical society clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prevention of drowning: 2019 Update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019 Dec;30(4S):S70-S86.

- Szpilman D, Bierens JJ, Handley AJ, Orlowski JP. Drowning. N Engl J Med. 2012 May 31;366(22):2102-10.

- Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine, 7th Edition, Paul S. Auerbach, Drowning and submersion injuries (Chapter 69) (2016).

- US Navy Diving Manual, Rev 7, Commander Naval Sea Systems Command (2016) Drowning/Near-drowning (Chap 3-5.4).

- Mott TF, Latimer KM. Prevention and treatment of drowning. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(7):576-582.

- Global report on drowning: preventing a leading killer, World Health Organization, Nov 17, 2014.

- NOLS Wilderness Medicine, 6th Edition, 2007. Tod Schimelpfenig, Drowning and cold-water immersion (Chap 14).

- American Red Cross Life Guarding Manual 2017.

- Bennett and Elliotts' Physiology and Medicine of Diving, 5th Edition, 2003. Chapter 6: Drowning and Nearly Drowning.

- Unknown author (2005), Part 10.3: Drowning. Circulation 112:IV-11-IV-135.

- Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of drowning, 2016: 236-251.

- MacLeod DB, Cortinez LI, Keifer JC, et al. The desaturation response time of finger pulse oximeters during mild hypothermia. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(1):65-71.

- Kober A, Scheck T, Lieba F, et al: The influence of active warming on signal quality of pulse oximetry in prehospital trauma care. Anesth Analg 2002; 95: pp. 961.

- Walker RA. Near Drowning Chapter 124. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine Manual, 8e. McGraw Hill; 2017.

- Kjaergaard J, Møller JE, Schmidt H, et al. Blood-pressure targets in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2022 Oct 20;387(16):1456-1466.

- Dankiewicz J, Cronberg T, Lilja G, et al. Hypothermia versus normothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(24):2283-2294.

- NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators, Finfer S, Chittock DR, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1283-1297.

- Wilmshurst PT, Nuri M, Crowther A, Webb-Peploe MM. Cold-induced pulmonary oedema in scuba divers and swimmers and subsequent development of hypertension. Lancet. 1989;1:62-65.

- Wester TE, Cherry AD, Pollock NW, et al. Effects of head and body cooling on hemodynamics during immersed prone exercise at 1 ATA. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(2):691-700.

- Smith R, Brooke D, Kipps C, Skaria B, Subramaniam V. A case of recurrent swimming-induced pulmonary edema in a triathlete: the need for awareness. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017 Oct;27(10):1130-1135.

- Smart DR, Sage M, Davis FM. Two fatal cases of immersion pulmonary oedema - using dive accident investigation to assist the forensic pathologist. Diving Hyperb Med. 2014 Jun;44(2):97-100.

- Santoso L. A diver with swimming-induced pulmonary edema and cardiac arrest. Chest. 2021;160(4): A1915 - A1916.

- Spencer S, Dickinson J, Forbes L. Occurrence, risk factors, prognosis, and prevention of swimming-induced pulmonary oedema: a systematic review. Sports Med Open. 2018 Sep 20;4(1):43.

- Davis FM. Immersion pulmonary edema—facts and fancies. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2016;43(6):744.

- Lindholm P, Lundgren CE. The physiology and pathophysiology of human breath-hold diving. J Appl Physiol [Internet]. 2009;106:284–92.

- Osborn waves. https://litfl.com/osborn-wave-j-wave-ecg-library/.

- Casey H, Dastidar AG, MacIver D. Swimming-induced pulmonary oedema in two triathletes: a novel pathophysiological explanation. J R Soc Med. 2014;107:450-452.

- Volk C, Spiro J, Boswell G, et al. Incidence and impact of swimming-induced pulmonary edema on Navy SEAL candidates. Chest. 2021 May;159(5):1934-1941.

- Hårdstedt M, Seiler C, Kristiansson L, et al. Swimming-induced pulmonary edema: diagnostic criteria validated by lung ultrasound. Chest. 2020 Oct;158(4):1586-1595.

- MacIver DH, Clark AL. The vital role of the right ventricle in the pathogenesis of acute pulmonary edema. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(7):992-1000.

- Seiler C, Kristiansson L, Klingberg C, et al. Swimming-induced pulmonary edema: evaluation of prehospital treatment with CPAP or positive expiratory pressure device. Chest. 2022 Aug;162(2):410-420.

- Shearer D., Mahon R. Brain natriuretic peptide levels in six basic underwater demolitions/SEAL recruits presenting with swimming induced pulmonary edema (SIPE) J Spec Oper Med. 2009;9(3):44–50.

- Roberts BW, Kilgannon JH, Hunter BR, et al. Association between early hyperoxia exposure after resuscitation from cardiac arrest and neurological disability: prospective multicenter protocol-directed cohort study. Circulation. 2018;137(20):2114-2124.

APPENDIX A: DROWNING PREVENTION FOR MILITARY PROVIDERS

GENERAL PREVENTION

- Respect the power of moving water and debilitating effects of cold water on the body.1-3 The effects of fast-moving water can be devastating for swimmers of all skill levels.

- Wear a personal flotation device (PFD) and have a PFD available for every person.1-2,4

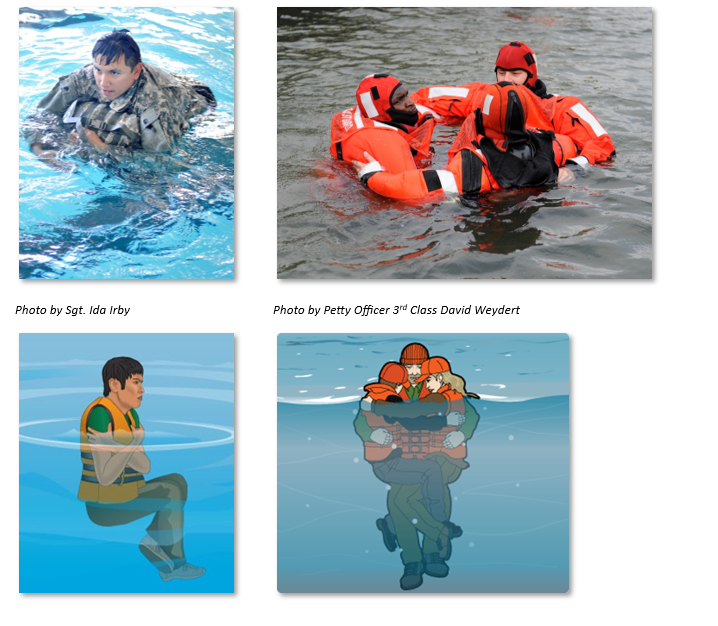

- Huddle – if in a group, everyone faces inward and huddle with arms interlocked.

- Get as much of body out of the water as possible (e.g., climb onto submerged boat) to reduce detrimental hypothermic effects of cold-water exposure.1-2,5

- Learn to swim, tread water, or float (not a substitute for PFD) and always swim with others.

- Have a well-developed safety and rescue plan that is exercised and practiced routinely.1-2

- Be aware of the behavior of submerging vehicles.

- Average vehicle takes 30 seconds to 2 minutes to sink.

- Once even partially submerged, windows and doors can be nearly impossible to open or kick out.

- Vehicle escape procedure SWOC: 6

- Seatbelts off

- Windows open

- Out immediately

- Children first

COLD WATER IMMERSION/SELF AID

- Sudden immersion in cold water ( < 91.4°F/33 °C) causes panic and reflexive gasp for air and rapid breathing which results in increased risk of aspiration, dysrhythmias.

- Prolonged exposure to cold water rapidly leads to incapacitation with diminished strength and coordination.1,15,7,2,3,5,8,9

- Follow the above instructions for escaping a vehicle (if warranted).

- Limiting time of exposure is critical. A general timeline is provided for guidance below with expected survival times listed in Table 1 at the beginning of CPG.

- Control breathing in order to survive shock of exposure during the initial one minute.

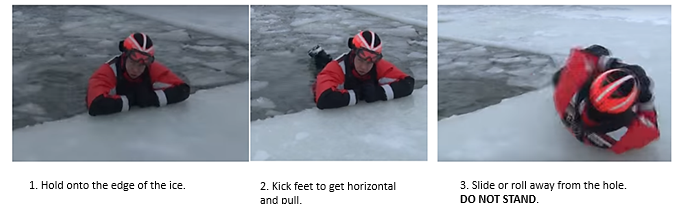

- Within 10 minutes, exposed individuals will become incapacitated and thus must move judiciously during this time. If able to reach and maintain control of the ice, the victim should hold on to the edge of the ice, kick his/her feet to become horizontal and pull. See ice rescue training images (Figure 4).

- Incapacitated individuals will generally become unresponsive due to hypothermia within the first hour.

- Onset of lethal dysrhythmia can occur within the first 2 hours.

- If a flotation device is available, exposed individuals should assume the “HELP” position (heat escape lessening posture) (Figure 5.) by bringing the knees to the chest and crossing the arms over them. Alternatively, in a group, the "huddle” position (Figure 5.) should be used.1-2

RESCUE AND IN-WATER RESUSCITATION

**Please note this is placed as an appendix based on standard international recommendations. This does not take the place of standard unit military training.**

- Identify and locate the victim (ask if there are more than one).1-2

- Victims are often seen motionless, sinking slightly below the surface.

- They may submerge into the water and never surface.

GOALS

- Initially the type of water does NOT matter (salt, fresh, clean, dirty).1-2

- Alert advanced life support as soon as possible.

- Accurately record environmental conditions including time of submersion, type and temperature of water and air, scuba diver (depth, time at depth, type of dive rig).

- As a clinical provider, if you find yourself being a rescuer, don’t become a victim. If you are being deployed on a Naval vessel – ensure you have taken all the courses about rescue swimming. Rescuer safety is a priority. Untrained rescuers or weaker swimmers should utilize alternative means of rescue such as the use of flotation devices, ropes, or paddles. Options for rescue include but are not limited to the following: 1-2,10

-

- Reach with an object from the safety of the shore or ship.

- Throw an object like a rope or flotation devices (this may help the victim stay afloat or the search and rescue team locate the victim.)

- Row (or paddle) a smaller craft to the victim if they are too far from shore to reach or have a floatation device thrown. The rescuer should ideally stay out of the water.

- Tow them into shore or away from danger in the water (i.e. swift water rescue).

- Go into the water (as a last resort) to rescue the victim if this is within the rescuer’s skill set.

- In water rescue, breaths should only be done when rapid extraction is NOT feasible. In water, chest compressions are NOT effective and should not be attempted. 1,11,12,16,

- Cervical spine injury in drowning victims is low (0.009%). Unnecessary cervical spine immobilization can impede delivery of rescue breaths via time of application and reduced airway opening. Routine stabilization of the cervical spine in the absence of circumstances that suggest a spinal injury (diving, boat accident, and fall from height) is not recommended. If suspected, protect cervical spine by assuming neck injury (use jaw thrust to open the airway and utilize C-Collar when feasible).1-3,9,17

- Hypothermic patients rescued from cold water are prone to lethal dysrhythmias (ventricular fibrillation). Patients should be handled as gently as possible to include the performance of life saving procedures (e.g., intubations) as these may precipitate dysrhythmias. Priority remains oxygenation, ventilation, and restoring circulation. 13

References

- Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine, 7th Edition, Paul S. Auerbach, Drowning and submersion injuries (Chapter 69) (2016).

- NOLS Wilderness Medicine, 6th Edition, 2007. Tod Schimelpfenig, Drowning and cold-water immersion (Chap 14).

- Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of drowning, 2016: 236-251.

- PFD Selection, Use, Wear & Care, available at https://www.dco.uscg.mil.

- S. Search and Rescue Task Force, Cold water survival (available at http://ussartf.org).

- Giesbrecht GG, McDonald GK. My car is sinking: automobile submersion, lessons in vehicle escape. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2010 Aug;81(8):779-84.

- Global report on drowning: preventing a leading killer, World Health Organization, Nov 17, 2014.

- Ashley D. GMO Manual: A medical reference for the operational medical officer 4th Edition, Submersion injuries.

- American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Part 9: Post–Cardiac Arrest Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S768–S786.

- 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR and ECC.

- American Red Cross Life Guarding Manual 2017.

- Bennett and Elliotts' Physiology and Medicine of Diving, 5th Edition, 2003. Chapter 6: Drowning and Nearly Drowning.

- European Resuscitation Council. Advanced challenges in resuscitation. Section 3: special challenges in ECC. 3F: cardiac arrest associated with pregnancy. Resuscitation. 2000 Aug 23;46(1-3):293-5.

- 2014 Videos of the Year: Ice Rescue Training (YouTube).

- US Navy Diving Manual, Rev 7, Commander Naval Sea Systems Command (2016) Drowning/Near-drowning (Chap 3-5.4).

- Szpilman D, Bierens JJ, Handley AJ, Orlowski JP. N Engl J Med. 2012 May 31;366(22):2102-10.

- Williams VF, Oh GT, Stahlman S. Update: Accidental drownings and near drownings, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2013-2017. MSMR. 2018 Sep;25(9):15-19. PMID: 30272989.

APPENDIX B: HYBERBARIC SUPPORT POINTS OF CONTACT

Hyperbaric Support Point of Contact Information (non-emergency)

Generally, military diving operations that involve deploying to a distant site, require that a recompression chamber be identified beforehand and on standby in the event of a diving casualty. Frequently, diving units will transport a Transportable Recompression Chamber System or Standard Navy Double Lock Recompression Chamber System to the location of diving operations. However, occasionally, diving units are unable to transport these recompression chamber systems and must utilize a non-Navy certified chamber in proximity to diving operations. Military diving units should follow unit policies and procedures. Chapter 6 of the Navy Dive Manual includes information on determining the level of chamber needed for a given dive profile. Additional resources are listed below in the event that organic assets are not available in the event of a diving related emergency.

NAMI Hyperbaric Medicine – Department 53HY - Mon-Fri from 07:30AM to 4:00PM CST

- (Phone) 850-452-2369

- (E-mail) usn.pensacola.navmedotcnamifl.list.nami-hyberbarics-department@health.mil

Supervisor of Salvage and Diving, USN (Via NAVSEA and DAN)

- https://supsalv.navy.mil/chamloc.asp?dest=00c3

- May be utilized to access list of available/certified hyperbaric oxygen chambers (CAC enabled).

Divers Alert Network (DAN)

- (E-mail) MEDIC@DAN.ORG (Subject Heading: Navy Chamber Request)

- (Phone) +1-(919)-684-9111

- (Fax) +(919) 493-3040

APPENDIX C: MEDICAL DEFINITIONS AND TERMINOLOGY

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION DEFINITIONS 1,2

1. Immersion: “some portion of the body is covered in water” (i.e. head is out of the water).

2.Submersion: “during submersion, the entire body, including the airway, is under water” (i.e. head is in the water).

3.Submersion injuries: “water-related conditions that do not involve the airway and respiratory systems.

4. Drowning: “the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from submersion/immersion in liquid.” The drowning process begins with respiratory impairment as the person’s airway goes below the surface of the liquid (submersion) or water splashes over the face while being completely in a liquid (immersion).1-3 Subdivided into 3 categories:

- Fatal drowning: “person dies at any time as a result of submersion/immersion with respiratory impairment.”

- Non-fatal drowning with morbidity: “person is injured at any time as a result of submersion/immersion with respiratory impairment but survives.”

- Non-fatal drowning without morbidity: “person survives uninjured from submersion/immersion event with respiratory impairment but survives.”

5. Water rescue: “submersion or immersion incident without evidence of respiratory impairment.”1-4

6. Shallow water blackout: “hyperventilating to decrease hypercapnic drive to breathe and prolong ability to stay under water such that hypoxemia results in unconsciousness.” The compulsion to breathe from hypercapnia (acidosis) is physiologically more potent than hypoxemia (except when subverted by hyperventilation – e. lowering CO2).5

7. Asphyxia: “a condition where breathing stops and both hypoxia and hypercapnia occur simultaneously due to: (1) the absence of gas to breathe; (2) the airway being completely obstructed; (3) respiratory muscles being paralyzed; or (4) respiratory center failing to send impulses to ” Running out of compressed air is a common cause of asphyxia in SCUBA diving.1,5,6

8. Drowning after shallow water diving: Diving into shallow water makes concussion, head injury, and cervical spine (C-spine) injury more common, so rescuer must balance C-spine precautions against time of extraction (normally in drowning C-spine precautions are not required because the risk is < 0.5%). Also consider drug/alcohol impairment.1,69.

9. Warm water drowning: Unplanned submersion → panic and violent struggle → gulping / swallowing of air and water → breath holding until hypoxia leads to unconsciousness → gag reflex relaxing resulting in passive influx of water → drowning if PFD does not keep airway out of the water.1

10. Cold water drowning: Impacts every organ system similar to complex trauma. Sudden immersion in cold water ( < 91.4°F/33 °C) causes panic, reflexive gasp for air and rapid breathing making:1-5, 8-10

- Inhalation/aspiration of water is more likely.

- Core temperature drop causing arrhythmias, confusion, incapacitation (diminished strength and coordination) increasing the chance of drowning.

- Water conduct heat away from the body 25 times faster than air leading to immersion hypothermia – impaired meaningful movement usually precedes.1,6,8

TERMS NOT TO USE

Terms NOT to use as they do not have diagnostic or therapeutic distinctions (although still widely used by medical professionals and the lay public, so important to be familiar with them).1,4,5,7,8,11

1. Wet drowning: “Fluid is aspirated into the lungs.” Aspiration of water occurs in only 80-90% of cases and does not change the treatment or management.

2. Dry drowning: “Fluid is not aspirated; death is due to laryngospasm and glottis closure.” Asphyxia still occurs secondary to laryngospasm occurring in 10-20% of cases, but no change in management. Difference is only relevant at autopsy.

3. Secondary drowning/Delayed onset of respiratory distress: Varied definitions with death occurring from 1-72 hours after initial resuscitation due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Fifteen percent of victims conscious at initial resuscitation subsequently die from ARDS.

4. Near drowning: “Suffocation by submersion in a liquid with at least temporary survival. Death from near drowning occurs after 24 hours.” Caused confusion because it had 20 different published definitions, most commonly if the person is rescued at any time, thus interrupting the process of drowning.

5. Immersion syndrome: “Sudden death immediately following submersion in very cold water” thought to be caused by vagal nerve stimulation resulting in overwhelming bradycardia.

6. Active drowning: Witnessed drowning.

7. Passive drowning: Unwitnessed drowning.

8. Fresh water vs. saltwater drowning: Typical human aspiration during drowning is 4 mL/kg. To change blood volume requires 8mL/kg, or to alter electrolytes require 22 mL/kg. Therefore, not clinically significant, and instead focus remains on hypoxemia, acidosis, and pulmonary injury rather than electrolyte or volume status.

- Freshwater: Hypervolemia (in animal models only, not humans, so no clinical relevance).

- Saltwater: Hypovolemia with hypernatremia (in animal models only, not humans, so no clinical relevance).

REFERENCES

- Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine, 7th Edition, Paul S. Auerbach, Drowning and Submersion Injuries (Chapter 69) (2016).

- Global report on drowning: preventing a leading killer, World Health Organization (2002).

- Wilderness Medical Society Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and treatment of Drowning 27, 236-251 (2016).

- Szpilman, D. et al. Drowning. New England Journal of Medicine. 366(22):2102-2110.

- US Navy Diving Manual, Rev 7, Commander Naval Sea Systems Command (2016) Drowning/Near-drowning (Chapter 3-5.4).

- NOLS Wilderness Medicine, 6th Edition, Tod Schimelpfenig, Drowning and Cold-Water Immersion (Chapter 14) (2007).

- Global report on drowning: preventing a leading killer, World Health Organization (2002).

- GMO Manual A Medical Reference for the Operational Medical Officer 4th Edition, LT Denis Ashley, Submersion injuries.

- S. Search and Rescue Task Force, Cold Water Survival.

- American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular. Circulation 2010;122:S768–S786.

- Prevention and Treatment of Drowning, Mott & Latimer.

APPENDIX D: CLASS VIII MEDICAL MATERIELS

Airway Management Supplies

- Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways – assorted sizes

- Bag-valve-mask (BVM) – adult and pediatric sizes

- Advanced airway kits (e.g., endotracheal tubes, stylets, laryngoscopes with blades, and video laryngoscope if available)

- Supraglottic airways (e.g., laryngeal mask airway - LMA)

- Suction equipment – portable suction units and tubing (nasal, oral, and ET tube)

- End-tidal CO₂ monitors (capnography equipment)

Ventilation and Oxygenation Supplies

- Portable oxygen tank with regulator – ideally 15 L/min capacity

- High-flow oxygen capability: masks and nasal cannulas

- Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) equipment if available (e.g., CPAP, BiPAP)

- Ventilator – preferably transport or field-appropriate model if available for prolonged transport

IV/IO Access and Fluid Resuscitation Supplies

- IV catheters and IV tubing – assorted sizes for adults and pediatric patients

- Intraosseous (IO) access kits

- Normal saline (NS) or Lactated Ringer’s (LR) solution – for resuscitation

- Pressure infusers for rapid infusion if necessary

- IV fluid warmer – optional but beneficial in preventing hypothermia

Circulation and Hemodynamics Support/Monitoring

- Automated external defibrillator (AED) – for cardiac arrest scenarios

- Cardiac monitor – capable of 3- or 5-lead EKG monitoring

- BP cuffs – both manual and automated, with adult and pediatric cuffs

- Stethoscopes

- Pulse oximeter – portable with spare batteries if possible

- Thermometer – digital or temporal for temperature monitoring

- Blood glucose monitor – to assess for hypoglycemia if needed

Temperature Management

- Warm blankets and space/emergency blankets

- External warming devices if available

- Hypothermia prevention kits for field use

Medication Administration Supplies

- Syringes and needles – assorted sizes for medication administration

- Medications – for emergency drugs such as epinephrine, atropine, and albuterol if indicated

Personal Protective Equipment

- Gloves – non-latex if possible

- Face shields or goggles

- Masks

Documentation Supplies

- Field medical record forms

- Pens, markers, and clipboard – to document care and maintain communication across teams

For additional information including National Stock Number (NSN), refer to Logistics Plans & Readiness (sharepoint-mil.us)

DISCLAIMER: This is not an exhaustive list. These are items identified to be important for the care of combat casualties.

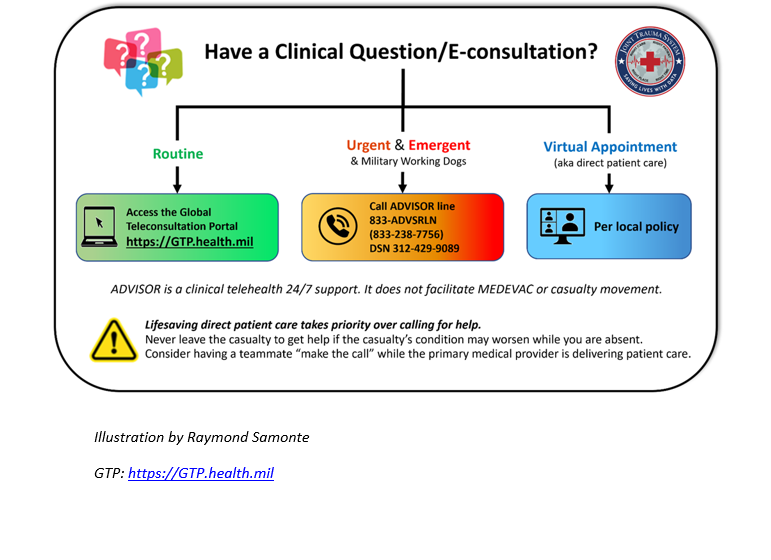

APPENDIX E: TELEMEDICINE/TELECONSULTATION

APPENDIX F: INFORMATION REGARDING OFF-LABEL USES IN CPGS

The purpose of this Appendix is to ensure an understanding of DoD policy and practice regarding inclusion in CPGs of “off-label” uses of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products. This applies to off-label uses with patients who are armed forces members.

Unapproved (i.e. “off-label”) uses of FDA-approved products are extremely common in American medicine and are usually not subject to any special regulations. However, under Federal law, in some circumstances, unapproved uses of approved drugs are subject to FDA regulations governing “investigational new drugs.” These circumstances include such uses as part of clinical trials, and in the military context, command required, unapproved uses. Some command requested unapproved uses may also be subject to special regulations.

Additional Information Regarding Off-Label Uses in CPGs

The inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is not a clinical trial, nor is it a command request or requirement. Further, it does not imply that the Military Health System requires that use by DoD health care practitioners or considers it to be the “standard of care.” Rather, the inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is to inform the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner by providing information regarding potential risks and benefits of treatment alternatives. The decision is for the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner within the practitioner-patient relationship.

Consistent with this purpose, CPG discussions of off-label uses specifically state that they are uses not approved by the FDA. Further, such discussions are balanced in the presentation of appropriate clinical study data, including any such data that suggest caution in the use of the product and specifically including any FDA-issued warnings.

With respect to such off-label uses, DoD procedure is to maintain a regular system of quality assurance monitoring of outcomes and known potential adverse events. For this reason, the importance of accurate clinical records is underscored.

Good clinical practice includes the provision of appropriate information to patients. Each CPG discussing an unusual off-label use will address the issue of information to patients. When practicable, consideration will be given to including in an appendix an appropriate information sheet for distribution to patients, whether before or after use of the product. Information to patients should address in plain language: a) that the use is not approved by the FDA; b) the reasons why a DoD health care practitioner would decide to use the product for this purpose; and c) the potential risks associated with such use.