K9 Clinical Practice Guideline #7- Abdominal Trauma

K9 Combat Casualty Care Committee

Introduction

- These clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) apply to deployed human healthcare providers (HCPs) in combat or austere areas of operations. Veterinary care is established at multiple locations throughout theater, and the veterinary health care team is the MWD’s primary provider. However, HCPs are often the only medical personnel available to MWDs that are critically ill or injured. The reality is that HCPs will routinely manage working dogs in emergencies before they are ever seen by veterinary personnel.

- Care by HCPs is limited to circumstances in which the dog is too unstable to transport to supporting veterinary facilities or medical evacuation is not possible due to weather or mission constraints; immediate care is necessary to preserve life, limb, or eyesight; and veterinary personnel are not available. HCPs should only perform medical or surgical procedures – within the scope of their training or experience – necessary to manage problems that immediately threaten life, limb, or eyesight, and to prepare the dog for evacuation to definitive veterinary care. Routine medical, dental, or surgical care is not to be provided by HCPs.

- Emergent surgical management of injured MWDs may be necessary by HCPs to afford a chance at patient survival. This should be considered only if:

- The provider has the necessary advanced surgical training and experience.

- The provider feels there is a reasonable likelihood of success.

- The provider has the necessary support staff, facilities, and monitoring and intensive care facilities to manage the post-operative MWD without compromising human patient care.

- Emergent surgical management should be considered only in Role 2 or higher medical facilities and by trained surgical specialists with adequate staff. Direct communication with a US military veterinarian is essential before considering surgical management, and during and after surgery, to optimize outcome.

Abdominal Injuries in Deployed MWDs

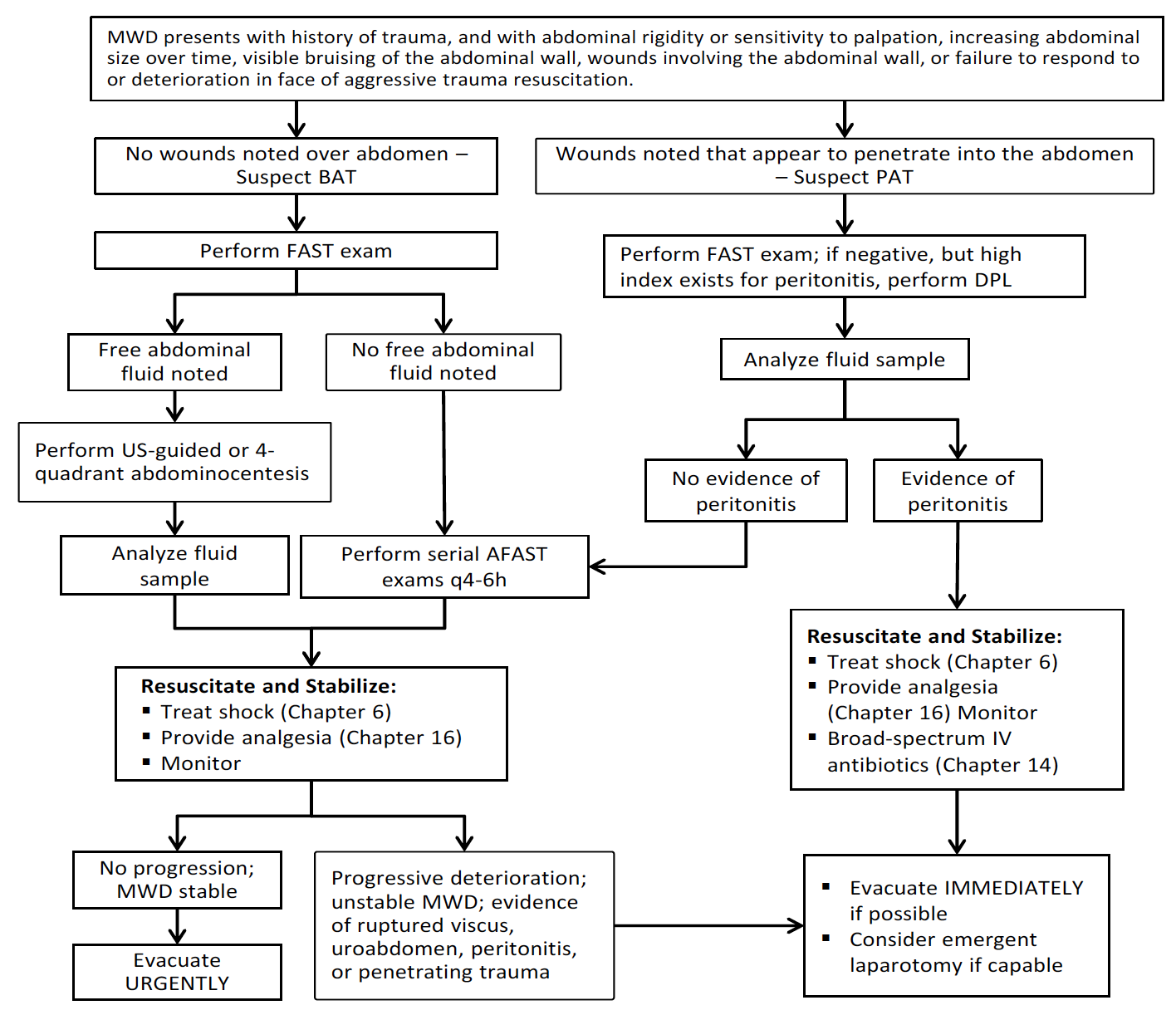

These injuries are the result of either blunt abdominal trauma (BAT) or penetrating abdominal trauma (PAT).1-7 Management of these types of injuries differs markedly. Conservative medical management is usually indicated for MWDs with blunt abdominal trauma; whereas, urgent exploratory surgery is generally recommended for MWDs with penetrating injuries. A clinical management algorithm for MWDs with abdominal trauma is provided. (See Figure 38).

Clinical Management Algorithm for MWDs with Abdominal Trauma

Figure 38. Clinical Management Algorithm for MWDs with Abdominal Trauma.

Physical Exam Finding Supporting Abdominal Trauma

Suspect significant intra-abdominal injury in any MWD that presents with abdominal rigidity or sensitivity to palpation, increasing abdominal size over time, visible bruising of the abdominal wall, or failure to respond to or deterioration in face of aggressive trauma resuscitation. Wounds involving more than the skin and superficial subcutaneous tissues dictate detailed examination to determine if the body wall was penetrated, and may require surgical exploration.

Diagnosis of Abdominal Trauma

The diagnostic method of choice for evaluating patients with suspected blunt abdominal trauma is the abdominal FAST (AFAST) exam, with ultrasound-guided or 4-quadrant needle abdominocentesis if free abdominal fluid is noted. Consider CT if advanced imaging is available.

AFAST

Perform an AFAST exam during the initial evaluation phase of every MWD with a history of trauma, acute collapse, or weakness. FAST is proven in dogs to be extremely reliable in detecting free abdominal fluid and can be performed rapidly during resuscitation.8

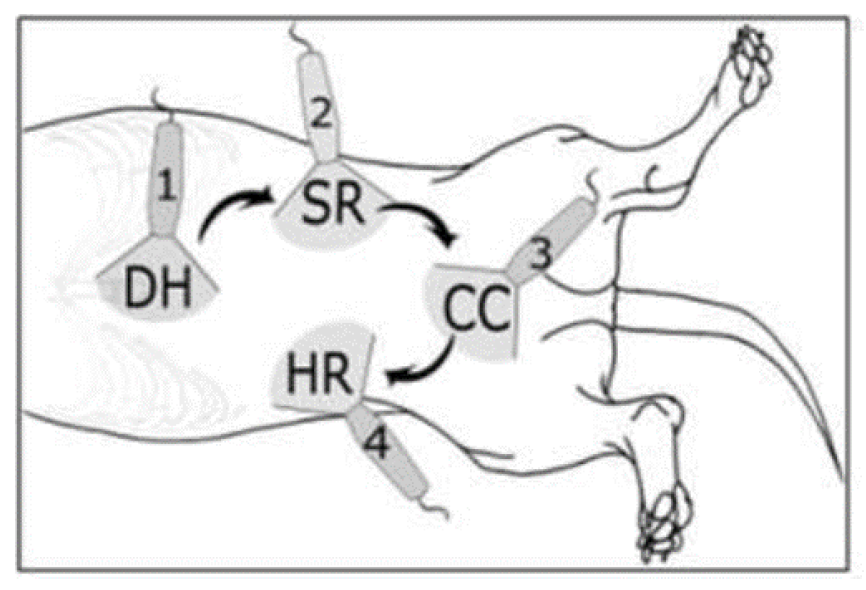

- Examine 4 quadrants. Probe placement for dogs includes the diaphragmatic-hepatic site (DH) caudal to the liver, the splenorenal site (SR) around the left kidney, the cystocolic site (CC) cranial to the urinary bladder, and the hepatorenal site (HR) around the right kidney.8 Figure 39 provides a schematic showing probe placement in dogs. Fan the probe in the cranial-caudal and lateral-medial planes.

Figure 39. Imaging Locations for AFAST.

Figure 39 shows ultrasound probe placement sites for AFAST scanning of dogs. The dog‘s head is to the left; the dog is in right lateral recumbency.

DH = diaphragmatic-hepatic

SR = splenorenal

CC = cystocolic

HR = hepatorenal

- Score the AFAST exam, with 1 point for each quadrant that has free fluid identified. Perform serial FAST exams every 4-6 hours and compare scores. MWDs with increasing scores should be monitored closely and prepared for URGENT evacuation or surgery, as exploratory surgery may be necessary for MWDs with scores of 3/4 or 4/48 or with clinical deterioration.

4- Quadrant Abdominocentesis

Perform a 4-quadrant abdominocentesis in any patient with free fluid in the abdomen.9 This technique is quick and easy to perform, and usually differentiates abdominal hemorrhage or biliary or urinary tract injury. The general rule of thumb is that a positive peritoneal tap is a reliable indicator that some hemorrhage has occurred or that free urine or bile is in the abdominal cavity, but that a negative tap does not rule these out.

- Place the dog in lateral recumbency. Clip the abdomen of hair and prepare for aseptic procedure.

- “Divide” the abdomen into 4 quadrants, and tap each quadrant sequentially, unless a positive yield is obtained in a quadrant. Perform abdominocentesis on the “down” quadrants, rolling the dog over for the opposite quadrants.

- A large bore needle (18 or 20 gauge) is quickly inserted perpendicular to and through the body wall approximately 2 inches off the midline in each quadrant. Alternatively, a large bore over-the-needle catheter can be aseptically fenestrated and inserted into the abdomen. This increases the likelihood for higher yield because the fenestrations are less likely to occlude.

- The presence of blood suggests intra-abdominal hemorrhage, and the presence of clear or yellowish fluid suggests urine.

- As much sample is collected by gravity drip or slight suction with a 3 cc syringe and saved in serum tubes and EDTA tube. The fluid is analyzed cytologically, and for glucose, lactate, hematocrit, total protein concentration, BUN or creatinine, bilirubin, amylase or lipase, ALT, and ALKP.

- Assess cytology for the presence of bacteria or other organisms, or fecal or food material that would suggest gastrointestinal rupture and contamination.

- The peritoneal fluid glucose and lactate concentrations can be measured and compared to serum levels to aid in differentiating possible septic peritonitis in the absence of cytological evidence. An increased abdominal fluid lactate >2.5 mmol/L or an abdominal fluid-to-peripheral blood lactate difference of >2 mmol/L strongly suggests a septic peritonitis.10,11 An abdominal fluid glucose concentration that is >20 mg/dL lower than peripheral blood glucose concentration strongly suggests a septic peritonitis.10,11

- The hematocrit and total protein concentration are compared to a simultaneously collected peripheral blood sample. If the hematocrit and total protein concentration are similar, significant hemorrhage into the abdomen is probable, and surgical intervention may be necessary, but base this decision on the patient’s status more than the actual number. If the hematocrit and total protein concentration of the abdominal fluid are very low, minor hemorrhage is more likely, and a more conservative approach – based on the patient’s status – is recommended.

- The presence of bilirubin suggests gall bladder injury, although this may not be present for several days after trauma.9 Amylase or lipase with values higher than systemic circulation suggests pancreatic trauma. A ratio of 1.4:1 in comparing abdominal fluid potassium with peripheral blood potassium concentrations has 100% sensitivity and specificity for uroperitoneum.12 Comparison of abdominal fluid creatinine to peripheral blood creatinine concentrations shows 86% sensitivity and 100% specificity for ratios >2:1.12 Elevated ALT suggests direct liver injury, and elevated ALKP suggests bowel injury or ischemia, but these are non-specific and can rarely be used to guide management decisions.

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage (DPL)

Consider DPL in any MWD in which major abdominal trauma is suspected, but AFAST and abdominocentesis are unrewarding.9 If available, CT or MRI may be better modalities.

- Use a specialized DPL catheter or aseptically fenestrate a large bore over-the-needle (OTN) catheter.

- Sedate the patient if necessary and locally anesthetize the site of catheter insertion using 20 mg lidocaine.

- Percutaneously insert the catheter; a small stab incision may be needed if a larger catheter is used.

- Immediately after entering the abdominal cavity, remove the needle and advance the catheter in a caudodorsal direction to avoid the omentum and cranial abdominal organs.

- Infuse 20 mL/kg warmed, sterile saline aseptically over 5-10 minutes.

- Aseptically plug the catheter and gently roll the MWD from side to side for several minutes to allow the infusate to mix.

- Either aspirate effluent or allow gravity-dependent drainage to collect a sample for analysis.

- Analyze the sample for the same parameters described for abdominocentesis.

Blunt Abdominal Trauma (BAT)

The usual organs in MWDs subjected to blunt trauma are the spleen, liver, and urinary bladder, in this order of frequency. Splenic and hepatic injuries are usually fractures of the organ; major vessel trauma is uncommon.1-7

Intra-abdominal hemorrhage.

Most hemoperitoneum cases in MWDs are due to splenic and hepatic fractures, which can vary markedly in size, with a significant difference in quantity of blood lost into the abdomen.

- The majority of MWDs with BAT and intra-abdominal hemorrhage that survive to admission can be successfully managed conservatively, since most of the time the source of hemorrhage is small liver and splenic fractures. These usually will spontaneously cease bleeding given time and conservative fluid therapy. Monitor the MWD closely, as some will require exploratory laparotomy and surgical correction of hemorrhage, especially those that do not respond or deteriorate.

- Given the difficulty in maintaining an abdominal counterpressure bandage, and the risk of respiratory compromise, do not apply an abdominal counterpressure bandage on a MWD.

- Patients with massive intra-abdominal bleeding need surgery to find the site of bleeding and surgically correct the loss of blood. There may be instances in which emergent laparatomy is necessary by HCPs to afford a chance at patient survival. See Emergent Abdominal Laparotomy in this CPG for guidance.

Urinary tract trauma.

Urinary bladder rupture, with uroperitoneum, is fairly common, especially if the animal had not voided before the trauma.

- MWDs with acute urologic trauma and uroperitoneum should be stabilized for other injuries, and aggressively managed for shock. Primary repair of a ruptured urinary bladder or other urologic injury must wait until the patient stabilizes to minimize the risk of complications associated with taking an unstable patient to surgery.

- In many cases, urologic injury is not apparent for several days after trauma, so a high index of suspicion must be maintained. Special studies (ultrasound, excretory urography, contrast urethrocystography) may need to be performed to rule out urologic trauma.

- In patients with known urologic tears and urine leakage, abdominal drains may be indicated if surgery is delayed for several days while the patient stabilizes. This will allow removal of urine, which will minimize chemical peritonitis and electrolyte and acid-base imbalances (metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia). Intensive fluid therapy to correct or prevent electrolyte and acid-base imbalances is often necessary, especially if several days have passed since traumatic injury.

- Surgical repair must only be performed after the patient is stabilized. Patients with severe uroabdomen need surgery to define the extent of injury and correct the problem. There may be instances in which emergent laparatomy is necessary by HCPs to afford a chance at patient survival. See Emergent Abdominal Laparotomy in this CPG.

Ruptured abdominal viscus.

Patients with a ruptured gastrointestinal viscus are candidates for emergent exploratory surgery to identify the part of the tract that is injured and allow primary repair. Delay in repairing bowel perforation can rapidly lead to septic peritonitis, septic shock, and rapid patient deterioration.13

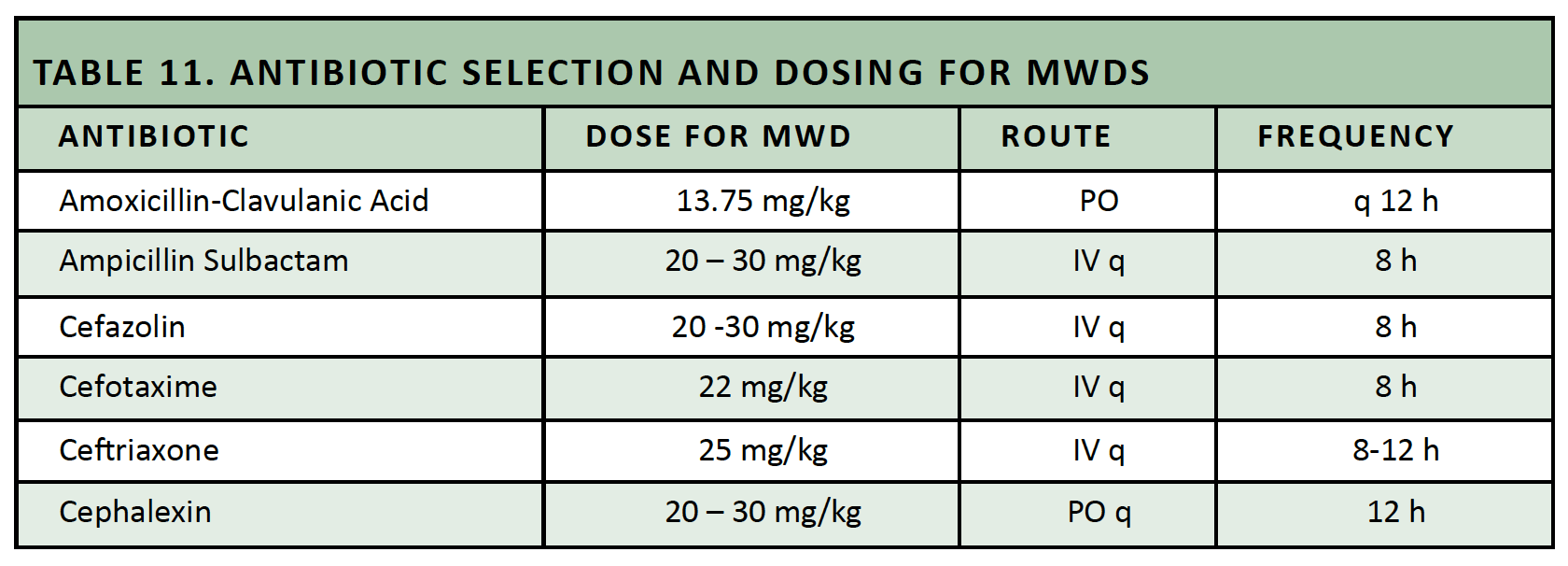

- Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy is vital, especially against anaerobic and gram negative bacteria. Table 11 lists antibiotic options for initial use in MWDs with ruptured viscus or septic peritonitis.

- Shock management is of special importance. Every attempt must be made to stabilize the patient as much as possible, with URGENT evacuation to a veterinary facility for definitive repair.

- Patients with ruptured abdominal viscus need surgery to define the extent of injury and correct the problem. There may be instances in which emergent laparatomy is necessary by HCPs to afford a chance at patient survival. See Emergent Abdominal Laparotomy in this CPG for guidance.

Table 11. Antibiotic Selection and Dosing for Military Working Dogs.

Penetrating Abdominal Trauma

Exploratory laparotomy as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality is clearly indicated in trauma patients if penetrating trauma is highly suspected or known, or if the patient‘s status deteriorates despite aggressive resuscitation attempts and major organ hemorrhage or injury is suspected or known.13

- Non-invasive diagnostic imaging is recommended in an attempt to confirm a suspicion of major internal organ injury. Perform AFAST, abdominocentesis, and/or DPL as necessary, and advanced imaging if available.

- Patients with penetrating abdominal injuries and a high index of suspicion for peritonitis, bowel injury, ruptured viscus, major hemorrhage, or other life-threatening problem need emergent surgery to further define the extent of injury and provide corrective surgery. There may be instances in which emergent laparatomy is necessary by HCPs to afford a chance at patient survival. See Emergent Abdominal Laparotomy in this CPG for guidance. Empiric antibiotic therapy is critical (See Table 11 above).

Emergent Abdominal Laparotomy

Some patients with severe abdominal trauma require surgery to define the extent of injury and attempt repair of the problem, remembering the caveats discussed previously.13

- Surgical management includes an approach through the ventral midline under general anesthesia with the dog in dorsal recumbency, to expose the abdominal cavity.

- A complete abdominal exploratory is necessary to define all injuries. Routine exploratory techniques used for people are appropriate for dogs.

- Surgical management will depend on the injuries noted. Expect hemoabdomen, liver and spleen trauma with hemorrhage, major vessel injuries with hemorrhage, bowel perforation, hollow viscus injuries, urinary tract injuries, and abdominal wall injuries. Repair of injuries in the dog is essentially the same as repair in human casualties.

- Abdominal wall closure is in 3 layers: 0 non-absorbable simple interrupted linea alba closure; 2-0 absorbable simple continuous subcutaneous closure; routine skin closure.

References

- Kolata RJ, Kraut NH, Johnston DE. Patterns of trauma in urban dogs and cats: A study of 1000 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1974;164:499-503.

- Kolata RJ, Johnston DE. Motor vehicle accidents in urban dogs: A study of 600 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1975;167:938-941.

- Simpson SA, Syring RS, Otto CM. Severe blunt trauma in dogs: 235 cases (1997-2003). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2009;19:588-602.

- Merck MD, Miller DM, Reisman RW, et al. Blunt Force Trauma. In: Veterinary Forensics: Animal Cruelty Investigations. Somerset: Wiley, 2012:97-120.

- Culp WTN, Silverstein DC. Thoracic and abdominal trauma. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K, eds. Small Animal Critical Care Medicine. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2015;728-733.

- Ressel L, Hetzel U, Ricci E. Blunt force trauma in veterinary forensic pathology. Vet Pathol 2016;53:941-961.

- Intarapanich NP, McCobb EC, Reisman RW, et al. Characterization and comparison of injuries caused by accidental and non-accidental blunt force trauma in dogs and cats. J Forensic Sci 2016;61:993-999.

- Lisciandro GR, Lagutchik MS, Mann KA, et al. Evaluation of an abdominal fluid scoring (AFS) system determined using abdominal focused assessment with sonography for trauma (AFAST) in 101 dogs with motor vehicle trauma. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2009;19:426-437.

- Jandrey KE. Abdominocentesis and diagnostic peritoneal lavage. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K, eds. Small Animal Critical Care Medicine. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2015;1036-1039.

- Bonczynski JJ, Ludwig LL, Barton LJ, et al. Comparison of peritoneal fluid and peripheral blood pH, bicarbonate, glucose, and lactate concentrations as a diagnostic tool for septic peritonitis in dogs and cats. Vet Surg 2003;32:161-166.

- Levin GM, Bonczynski JJ, Ludwig LL, et al. Lactate as a diagnostic test for septic peritoneal effusions in dogs and cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2004;40:364-371.

- Schmiedt CW, Tobias KM, Otto CM. Evaluation on abdominal fluid:peripheral blood creatinine and potassium ratios for diagnosis of uroperitoneum in dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2001;11:275-280.

- Volk SW. Peritonitis. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K, eds. Small Animal Critical Care Medicine. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2015;643-648.