Module 9: Circulation Hemorrhage Control in TFC

Joint Trauma System

Module 9: Circulation and Hemorrhage Control in TFC

Over the next three modules, we will discuss circulation assessment and management in the Tactical Field Care (TFC) setting. This first module will focus on hemorrhage control while the subsequent modules will address shock and fluid resuscitation. The didactic presentation will review several hemorrhage control principles and introduce a few new ones, and skills stations will provide an opportunity to get hands-on practice for the procedures you will need to master.

All Service Members and Combat Lifesaver training teaches basic hemorrhage control principles and interventions, with additional skills covered in the Combat Medic/Corpsman (CMC) training. As Combat Paramedic/Provider (CPP) professionals, it is important to understand what their training and anticipated skill set is, in order to assume care for the casualty and potentially initiate more advanced treatments.

The Curriculum Change Log serves as a centralized reference to quickly track recent updates to training materials. It supports trainers by promoting clear communication, accountability, and alignment, helping stakeholders and learners understand what changes were made, why they were implemented, and when they occurred.

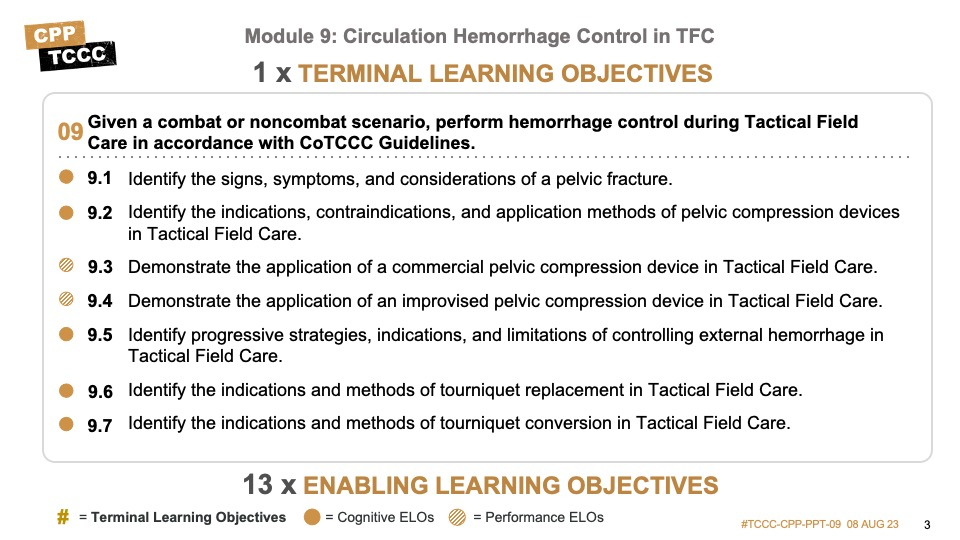

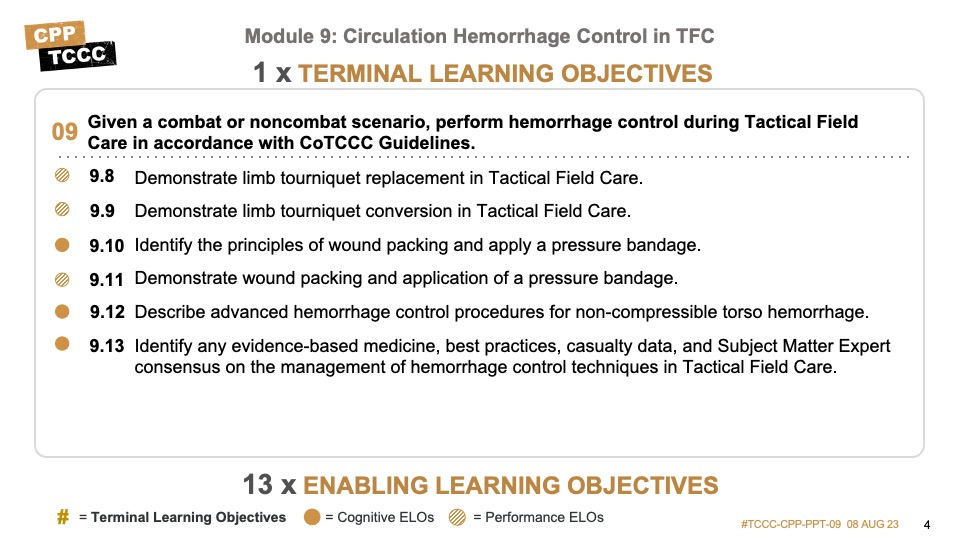

There are eight cognitive and five performance learning objectives for the circulation–hemorrhage control module.

The cognitive learning objectives include describing the progressive strategies and limitations of controlling external hemorrhage, identifying the signs and symptoms of pelvic fractures, and the indications, contraindications, and application methods of pelvic compression devices (PCDs), identifying the principles of wound packing and pressure bandages, identifying the indications and techniques for both tourniquet (TQ) replacement and tourniquet conversion, describing advanced hemorrhage control procedures for non-compressible torso hemorrhage, and understanding the level of evidence supporting all of these principles.

The performance learning objectives are applying both a commercially available PCD and an improvised PCD, wound packing and pressure bandage application, tourniquet replacement, and tourniquet conversion.

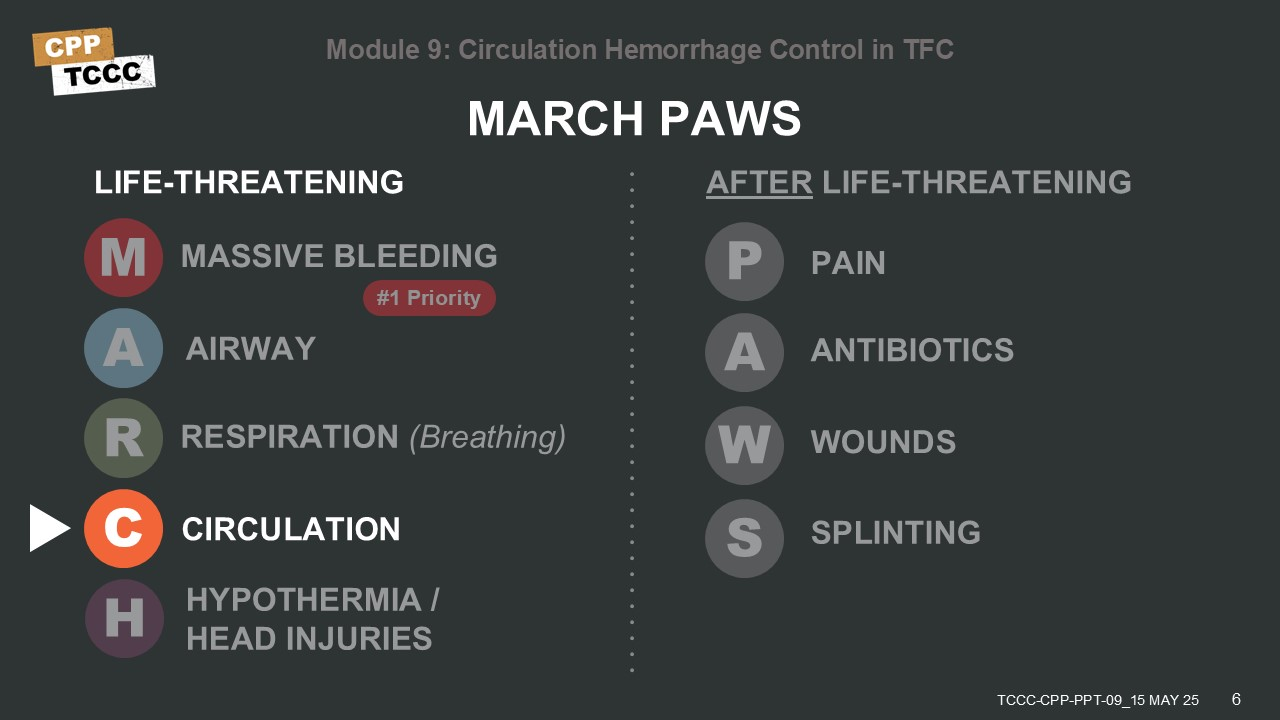

Circulation assessment and management is the “C” in the MARCH PAWS sequence.

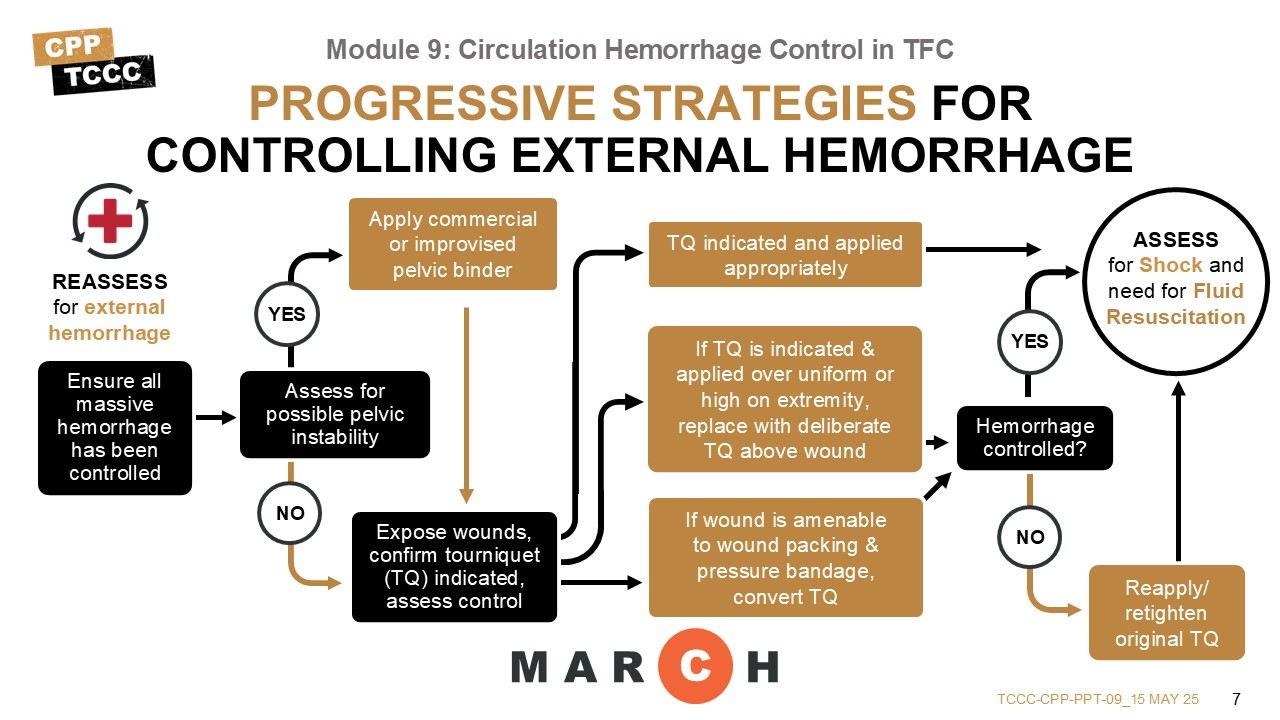

At this point in the assessment and management of a casualty, attention can be directed toward a more comprehensive evaluation of all hemorrhage. This includes both potential life-threatening internal hemorrhage, as well as a reassessment of prior interventions in external hemorrhage. Before talking about the specifics, it is useful to look at a progressive strategy for external hemorrhage control.1

Although massive external hemorrhage should have already been addressed, the initial action in this phase should be to ensure that there are no untreated sources of massive bleeding. If there are, they should be addressed with the methods previously described.

If no evidence of persistent massive external hemorrhage is found, the potential for massive internal hemorrhage should be evaluated. In recent conflicts, a common cause of this has been bleeding from pelvic fractures. So, a review of the risk factors for pelvic fracture should be performed, and a PCD placed, if indicated.

The next step is to expose any wounds, and reassess all previously applied tourniquets and dressings with pressure bandages to ensure bleeding is still being controlled. If there is still bleeding, this may be controlled by tightening a previously placed tourniquet or may require a second tourniquet be applied side-by-side. At this point, you can also determine if the bleeding from the wound requires continued use of a tourniquet to maintain control.

If the wound appears to require a tourniquet to control bleeding, and the current tourniquet was placed above the uniform (for example, a high and tight tourniquet), apply a second tourniquet directly on the skin 2-3 inches above the wound to replace the original tourniquet, ensuring bleeding is still controlled.

Occasionally, a tourniquet is placed principally because of the tactical situation and the need to ensure bleeding was rapidly addressed, but the bleeding might be controlled without a tourniquet. In those cases, consider converting bleeding control from a tourniquet to wound packing and pressure bandages, if the tourniquet has been on for less than 2 hours. Continue to reassess tourniquets for potential conversion to hemostatic dressings and pressure bandages at least every two hours, unless there has been an amputation; however, do not attempt tourniquet conversion if the tourniquet has been on for six or more hours.

After these measures, continue the casualty assessment by addressing the rest of the circulation phase objectives: assessing and managing shock, to include establishment of intravenous access and fluid resuscitation.

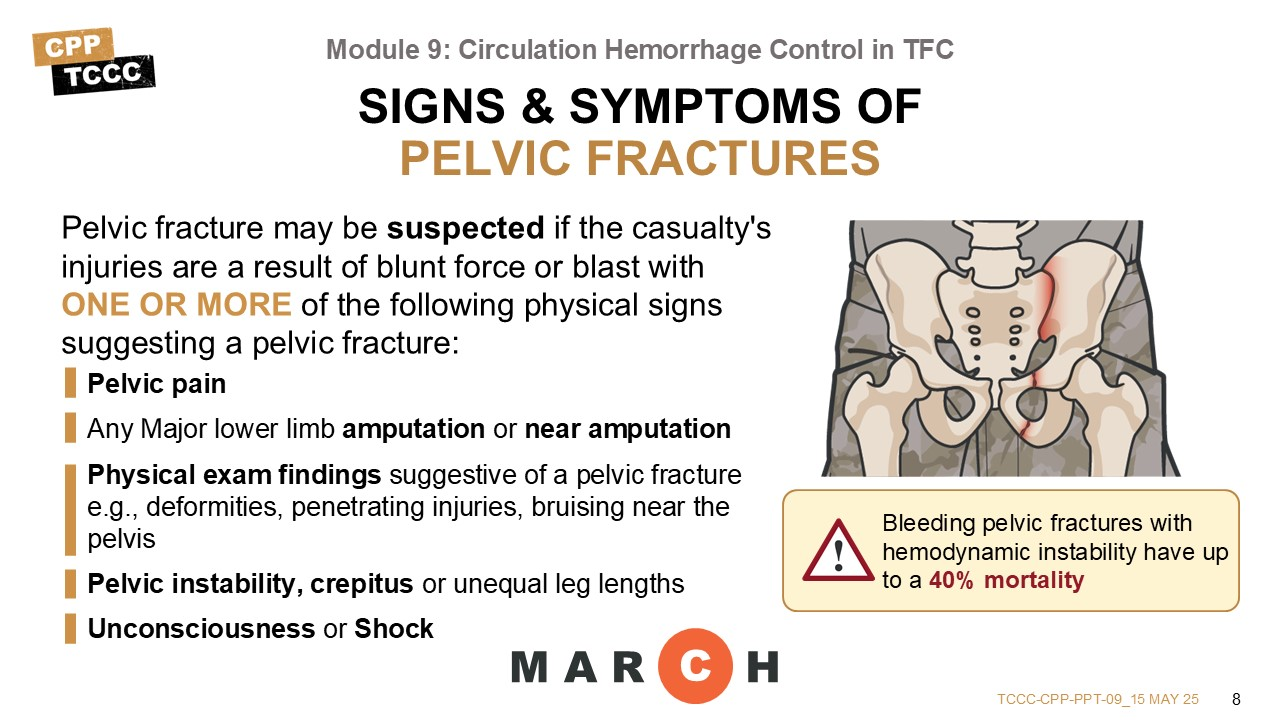

If the casualty is not experiencing persistent massive external hemorrhage, the potential for massive internal hemorrhage from a pelvic injury should be assessed. Most pelvic fractures are associated with dismounted improvised explosive device (IED) attacks accompanied by amputations, but they also occur in severe blunt trauma (such as motor vehicle crashes, aircraft mishaps, hard parachute landings, and falls). 26% of service members who died in OEF/OIF had a pelvic fracture,2 and bleeding pelvic fractures with hemodynamic instability have up to a 40% mortality.3, 4

Several major vessels run alongside the pelvic bones and can be disrupted by the sharp edges of a fracture, and are in anatomic locations that do not allow for effective direct or indirect pressure to be applied.

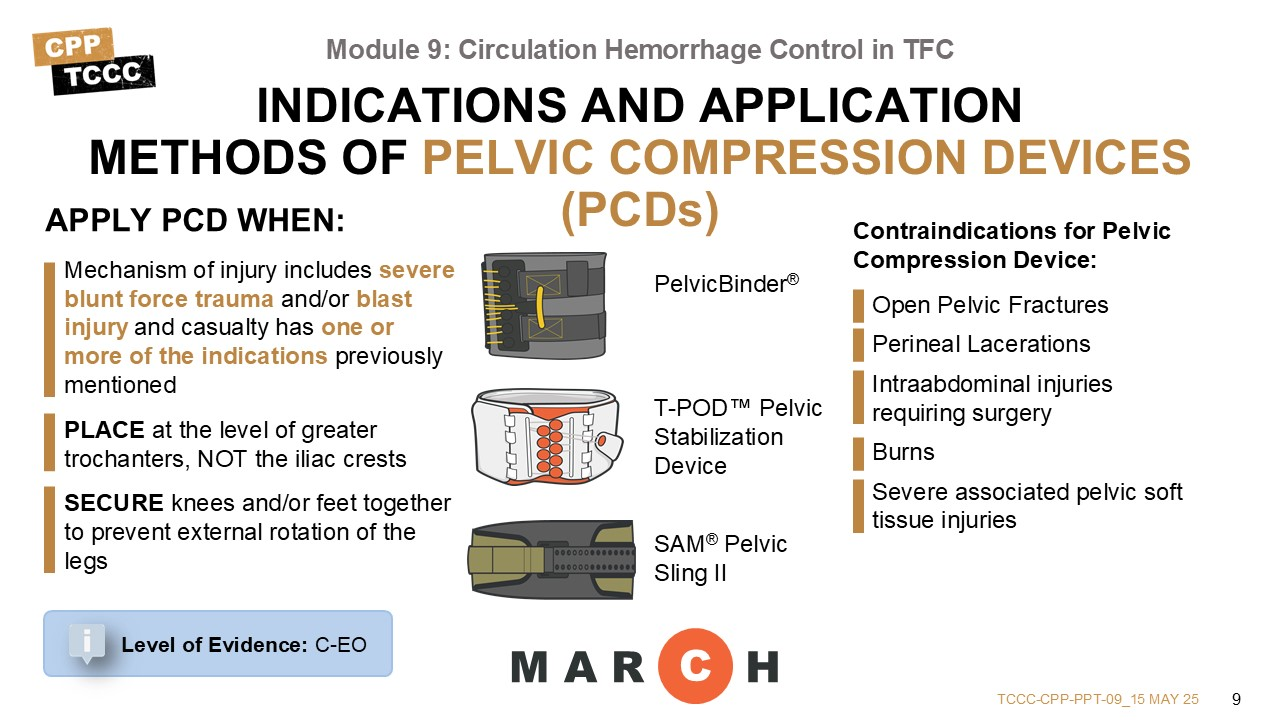

Pelvic fracture should be suspected in any casualty who suffers severe blunt force or blast injury and has one or more of the following indications:5

- Pelvic pain

- Any major lower limb amputation or near amputation

- Physical exam findings suggestive of a pelvic fracture (for example, laceration or bruising at bony prominences of the pelvic ring, crepitus, a deformed or unstable pelvis or unequal leg lengths)

- Unconsciousness

- Shock

Additional signs include scrotal, perineal, or perianal bruising, blood at the urethral meatus or massive hematuria, blood in the rectum or vagina, or neurologic deficits in lower extremities.6

Many prior courses have taught combat medics (and others) to check for pelvic instability by applying downward pressure on the anterior ilia (also called “opening the book”), but this causes further damage if a pelvic fracture is present and should NOT be done.7, 8

If you must move the PCD to access the groin or pelvic area for other critical casualty management purposes, temporarily move it to the upper thighs, and replace it as soon as possible. Every effort should be made to control bleeding coming from an open pelvic fracture or associated injuries

Contraindication for Pelvic Compression Device

- Open Pelvic Fractures

- Perineal Lacerations

- Intra-abdominal injuries requiring surgery

- Burns

- Severe associated pelvic soft tissue injuries may necessitate external fixation of the pelvis instead of pelvic binder

Open fracture to the pelvis may lacerate the rectum, perineum, or vagina, and an obvious source of external blood loss may not be readily apparent.

If the mechanism of injury raises the suspicion of a pelvic injury (IEDs, blasts, motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), etc.) and/or the five major signs and symptoms we just reviewed are present, then a PCD should be applied.9

There are several commercially available PCDs that could be considered, and although the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC) previously evaluated and recommended some of them, others have since become available and there is no longer a COTCCC-recommended pelvic compression device list. Commercial PCD examples include the PelvicBinder®, the T-POD™ Pelvic Stabilization Device, and the SAM® Pelvic Sling II.

Of note, two of the junctional hemorrhage control devices also provide pelvic stability and could be considered: the SAM Junctional Tourniquet (SJT) and the Junctional Emergency Treatment Tool (JETT™).

There is no evidence that any one commercial compression device is better than another.10, 11, 12

Whichever PCD is used, it should be placed at the level of greater trochanters, NOT the iliac crests. In one study 40% of the pelvic binders were placed too high, resulting in inadequate reduction of the pelvic fracture and possibly increased bleeding.13, 14

Also, external rotation of the lower extremities is commonly seen in casualties with displaced pelvic fractures, which may increase the dislocation of pelvic fragments. Secure the knees and/or feet together to prevent external rotation and improve the effect of the PCD.15

If you must move the PCD to access the groin or pelvic area for other critical casualty management purposes, temporarily move it to the upper thighs, and replace it as soon as possible.

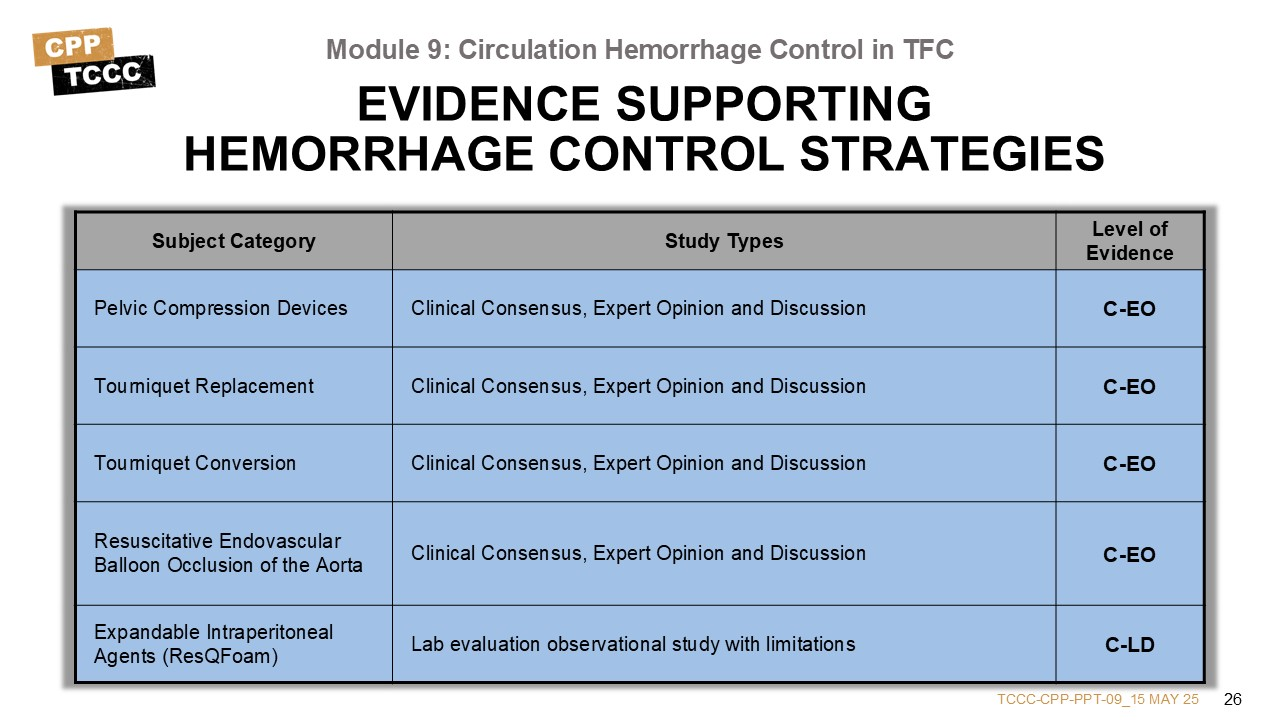

The evidence supporting the stabilization of pelvic fractures and reduced need for blood transfusions, when PCDs are properly applied, comes from nonrandomized studies, but the evidence supporting improved survival is lacking.

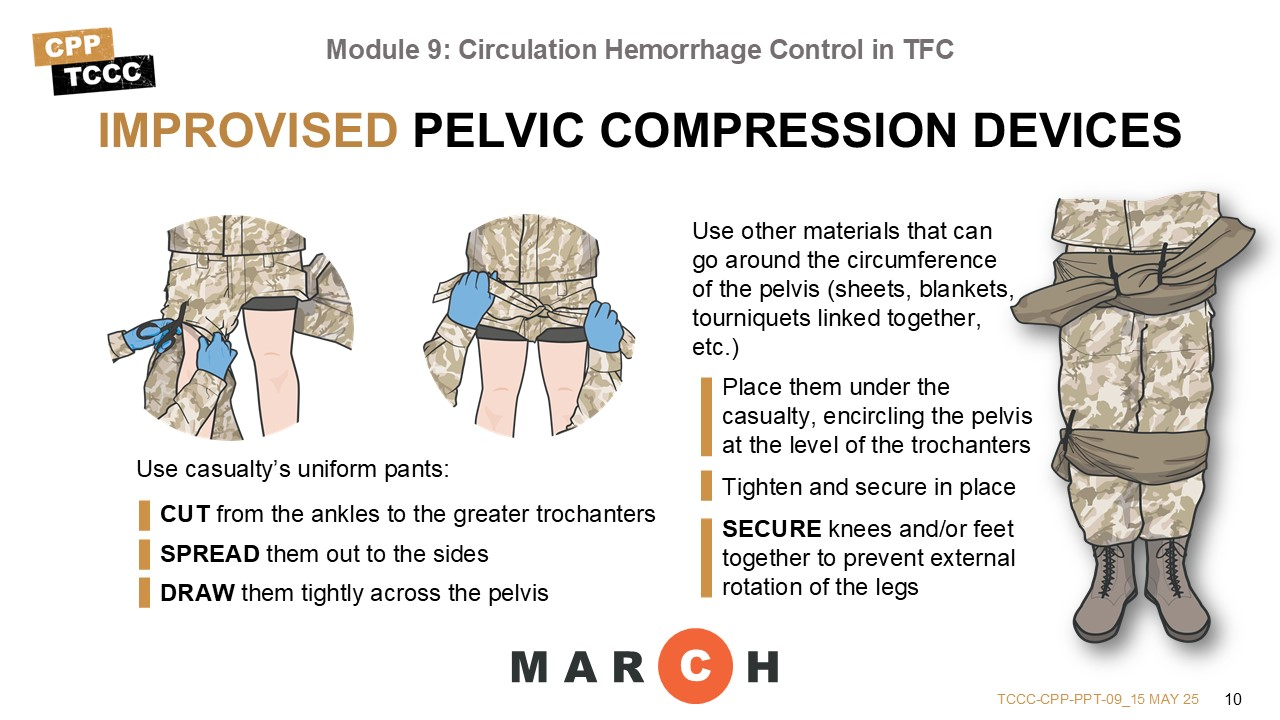

Ideally, every suspected pelvic fracture will be managed with a commercial PCD. But there are often only a handful of them available locally, and sometimes an improvised PCD must be considered.

In several studies evaluating the sheeting technique, where a sheet is wrapped circumferentially around the pelvis and tightened,17 the ability to stabilize pelvic fractures was nearly equivalent to commercial PCDs when properly applied.18,19,20

A common approach to improvisation is to use the casualty’s uniform pants as the binding materials by cutting them open from the ankles to the level of the greater trochanters, spreading them out to the sides like wings, and then drawing them tightly across the pelvis and tying them in a square knot to secure them and maintain pressure.21

But if the pants are torn or cannot be used, compression can be exerted by using any materials that can go around the circumference of the pelvis (for example, sheets, blankets, tourniquets linked together, elastic wraps, etc.). They would be placed, encircling the pelvis at the level of the trochanters, and then tightened and secured in place.

As with a commercial PCD, you would still want to prevent external rotation of the lower extremities by tying the casualty’s knees and/or feet together.

This video will go over the proper techniques for applying a commercial and improvised PCD.

PELVIC COMPRESSION DEVICE

The following skill cards will demonstrate applying both commercial and improvised PCDs.

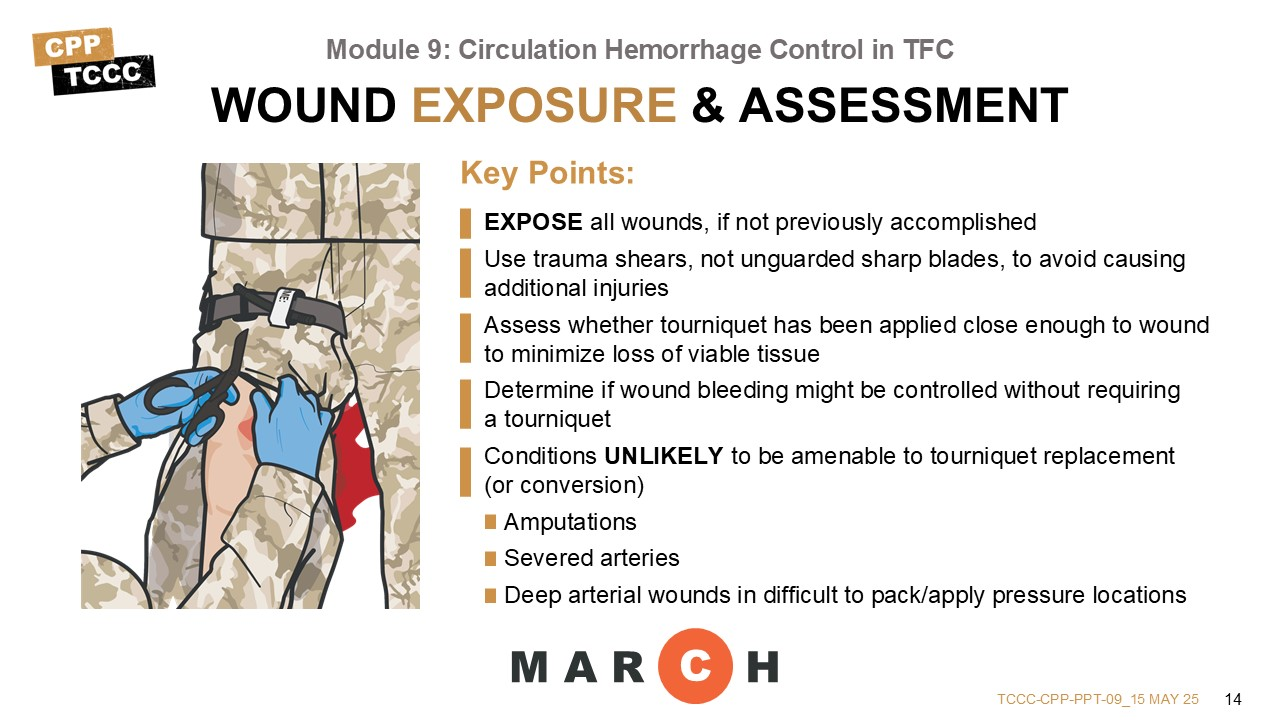

After reassessing massive hemorrhage control and applying a PCD, if appropriate, the next step is to expose any wounds, if that has not already been accomplished. Wound exposure should be accomplished using trauma shears rather than an unguarded blade to prevent further injury to the extremity.22 A principal objective of exposing wounds is to determine if the bleeding might be controlled without a tourniquet and/or to assess whether a tourniquet might be applied closer to the wound to preserve as much viable tissue as possible.

There is no precise set of parameters that will universally help make the determination of whether a tourniquet is necessary, but typical injuries that will continue to require a tourniquet include some obvious injuries like amputations and deep wounds that resulted in severed arteries, whereas more superficial injuries not involving the arteries may be more easily controlled.23, 24 However, sometimes the extent of the wound isn’t clearly known just based on the external view of the wound.25, 26

The tactical considerations during Care Under Fire or the uncertainty of the extent of bleeding during the massive hemorrhage phase in Tactical Field Care will sometimes lead to a bleeding control decision that can be managed differently once the situation is more controlled and more information can be gathered from the exposed wound. If the reassessment determines that the prior tourniquet was not needed, then remove the tourniquet, dress the wound, and note the time of tourniquet removal on the TCCC Casualty Card.27

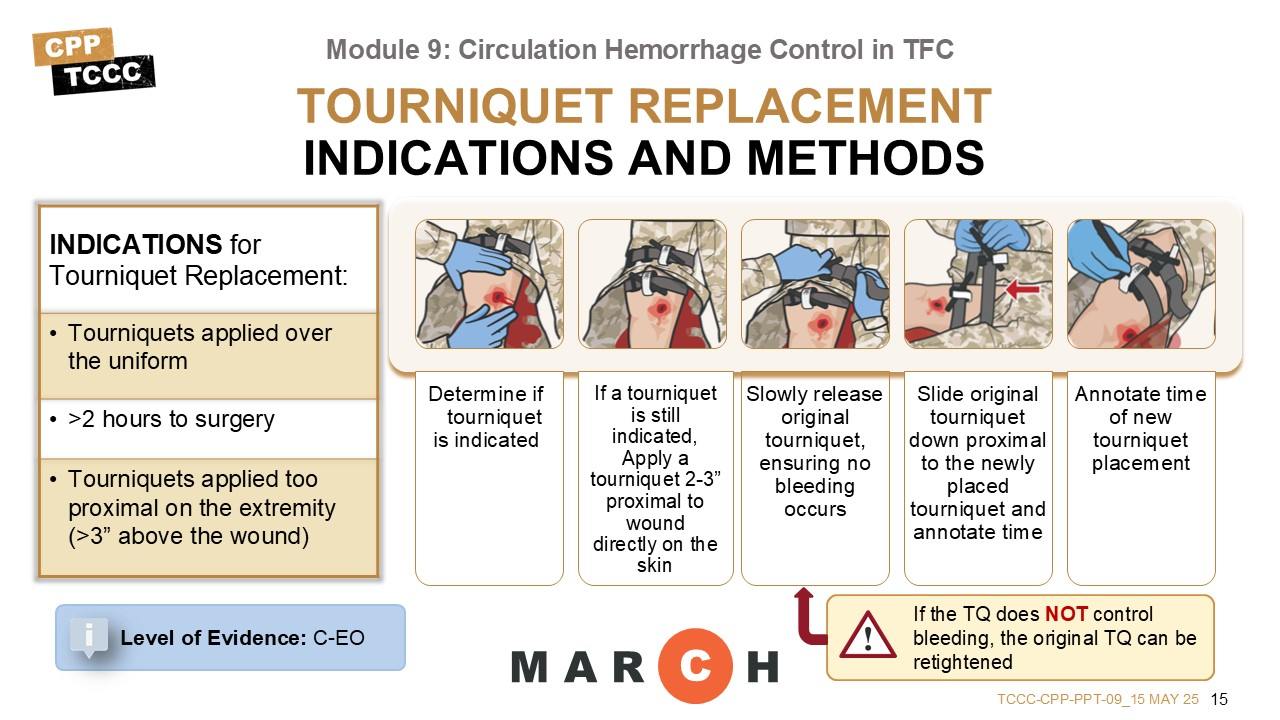

We’ll spend the next couple of minutes talking about the indications and processes for replacing tourniquets and for converting tourniquets.

In massive hemorrhage you learned that tourniquets should be applied more deliberately in the TFC setting, to maximize effectiveness and minimize the amount of healthy tissue that might be impacted by a tourniquet placed too high on the limb. So, if a tourniquet is, in fact, necessary, replace high and tight (hasty) tourniquets or tourniquets applied over the clothing with more deliberate (directly on the skin) tourniquets. Tourniquets applied over clothing are not as effective as tourniquets applied directly to the skin.

This is done by placing a replacement tourniquet directly on the skin, 2-3 inches above the wound and tightening it. Then, slowly release the original tourniquet over one minute, while monitoring the casualty for signs of recurrent bleeding or resumption of a distal pulse. Slide originally placed tourniquet(s) down, but leave in place proximal to the newly placed tourniquet. In cases of recurrent bleeding or pulses, the original tourniquet can be retightened and the replacement tourniquet can be tightened further, or repositioned and tightened further.

Afterwards, the original tourniquet is slowly released again to confirm bleeding control. It may require a second tourniquet be placed side-by-side with the replacement tourniquet, as well. Occasionally an attempt to replace a tourniquet will not be successful, and reverting back to the prior tourniquet location may be needed.

If the initial tourniquet remains tightened in its original position, there is a risk of a compartment syndrome developing between the two tourniquets. But rather than removing the original tourniquet completely, it can be slid down the extremity and positioned just proximal to the replacement tourniquet, but only partially tightened by having the slack of the tourniquet removed and the strap secured to prevent it from catching or being in the way during casualty assessments or movements.

The level of evidence supporting the guidance for tourniquet replacement in the tactical environment is based on Clinical Consensus, Expert Opinion, and Discussion.

This video will go over the process of replacing a tourniquet in Tactical Field Care.

TOURNIQUET REPLACEMENT

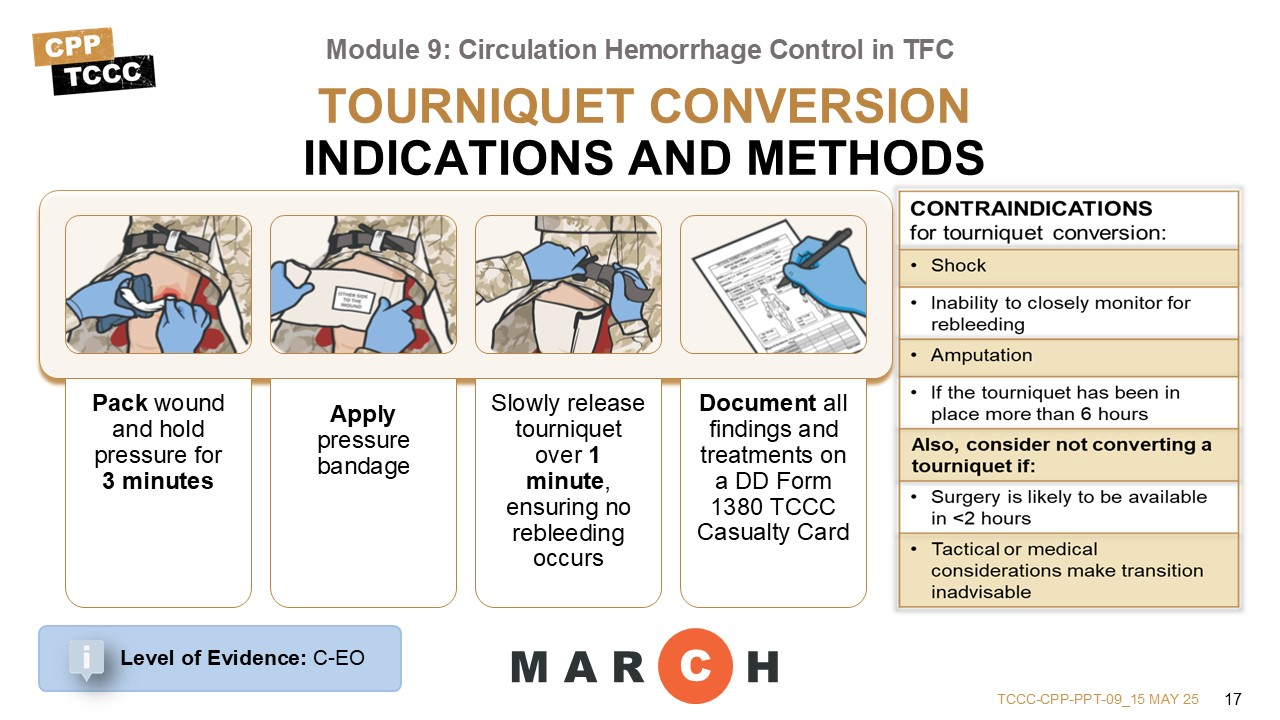

Every effort should be made to convert tourniquets in less than 2 hours if bleeding can be controlled by other means unless there has been an amputation, the casualty is in shock or you cannot closely monitor the wound for re-bleeding;28, 29 However, do not attempt tourniquet conversion if the tourniquet has been on for six or more hours.30 Also, consider leaving the tourniquet in place if the tactical or medical considerations make the transition to other hemorrhage control methods inadvisable, or if it is likely that the casualty will have access to surgery within 2 hours.31

While the original tourniquet is still in place controlling the bleeding, pack the wound with hemostatic gauze, if available, and hold pressure for three minutes. Then apply a pressure bandage over the dressing, maintaining pressure. Afterward, slowly release the tourniquet (over at least one minute) while closely observing for bleeding. If the wound packing and pressure bandage do not control the bleeding, retighten the tourniquet or follow the steps to replace the tourniquet if it is above the clothing, like a high and tight tourniquet.32,33 In cases where the conversion has failed, it is appropriate to try again within the next two hours, as long as it hasn’t been more than six hours since the original tourniquet was applied.34,35

If the conversion is successful, loosen the tourniquet and move it down to just above the pressure dressing, loose but with no slack in the strap, in case it is needed later, and annotate the time of tourniquet removal on the DD Form 1380, TCCC Casualty Card.36 Periodically reassess the wound for recurrent bleeding and reassess after any casualty movements.

The evidence to support the conversion of tourniquets, when amenable, relies largely on retrospective reviews and subject matter expert consensus. There are a handful of animal model prospective studies on hemostatic agents that tend to support its use, as well. In cases requiring the use of a tourniquet, the caregiver removes the tourniquet every 2 hours and assesses the bleeding; if the bleeding has stopped, then the tourniquet should be replaced with a pressure bandage to minimize tissue damage.

The level of evidence supporting the guidance for tourniquet conversion in the tactical environment is based on Clinical Consensus, Expert Opinion, and discussion.

This video will go over the process of converting a tourniquet using wound packing and pressure bandages in TFC.

TOURNIQUET CONVERSION

Before moving on to talk about tourniquet conversion, let’s review some of the points from the massive hemorrhage discussion about wound packing and pressure bandages.

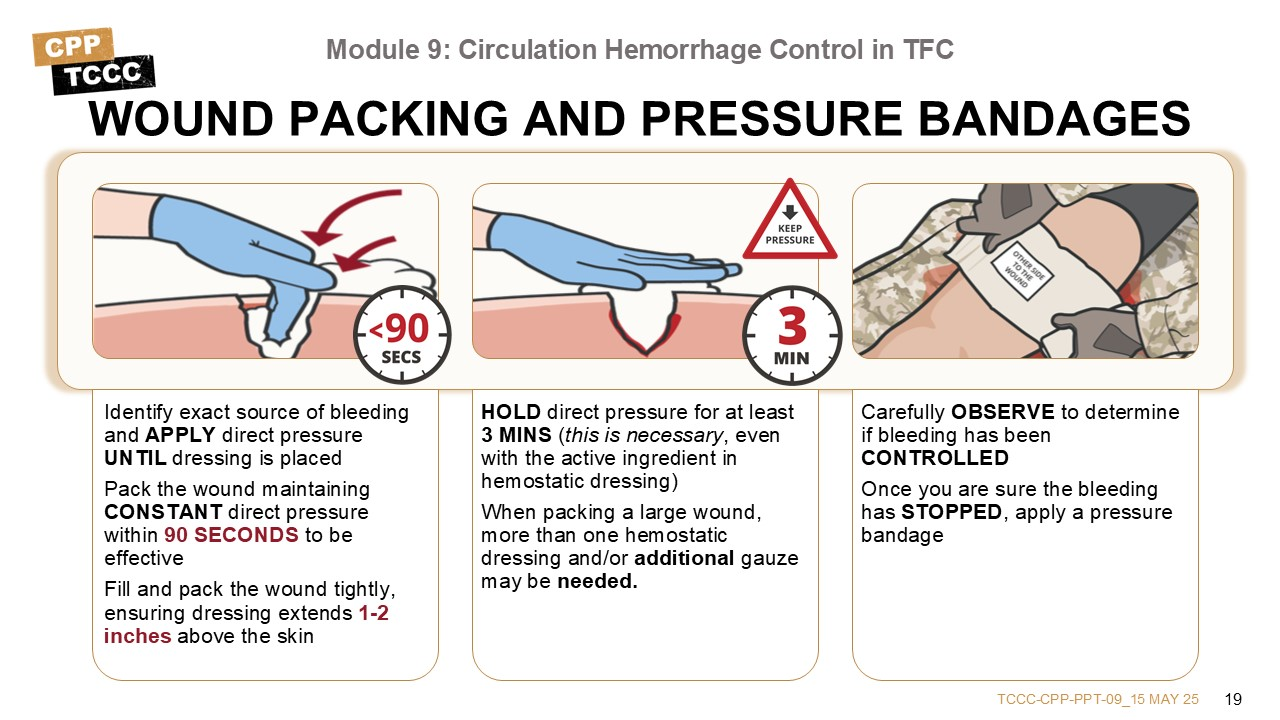

Tourniquets are not required for all extremity bleeding. Occasionally, some lacerations that can be controlled by hemostatic dressings will have a tourniquet applied during the massive hemorrhage phase.38 If you assess that a wound is amenable to control without a tourniquet, the skills taught in the massive hemorrhage module can be used.

CoTCCC-recommended hemostatic dressings, including Combat Gauze®, ChitoGauze®, and Celox™ Gauze,39 are safe and contain active ingredients that assist with blood-clotting at the site of active bleeding.40 To effectively form a clot and stop bleeding, hemostatic dressing must be packed into the wound to maximize contact at the active source of bleeding with direct pressure applied over the wound for at least 3 minutes.41 Afterward, all dressings for significant bleeding should be secured with a pressure bandage while maintaining pressure on the wound throughout the process of applying the pressure bandage.42

Also, wound packing and pressure bandage application can be used at this stage for larger bleeding wounds that were not previously addressed, but that should be controlled prior to the wound phase (or the “W” of MARCH PAWS).

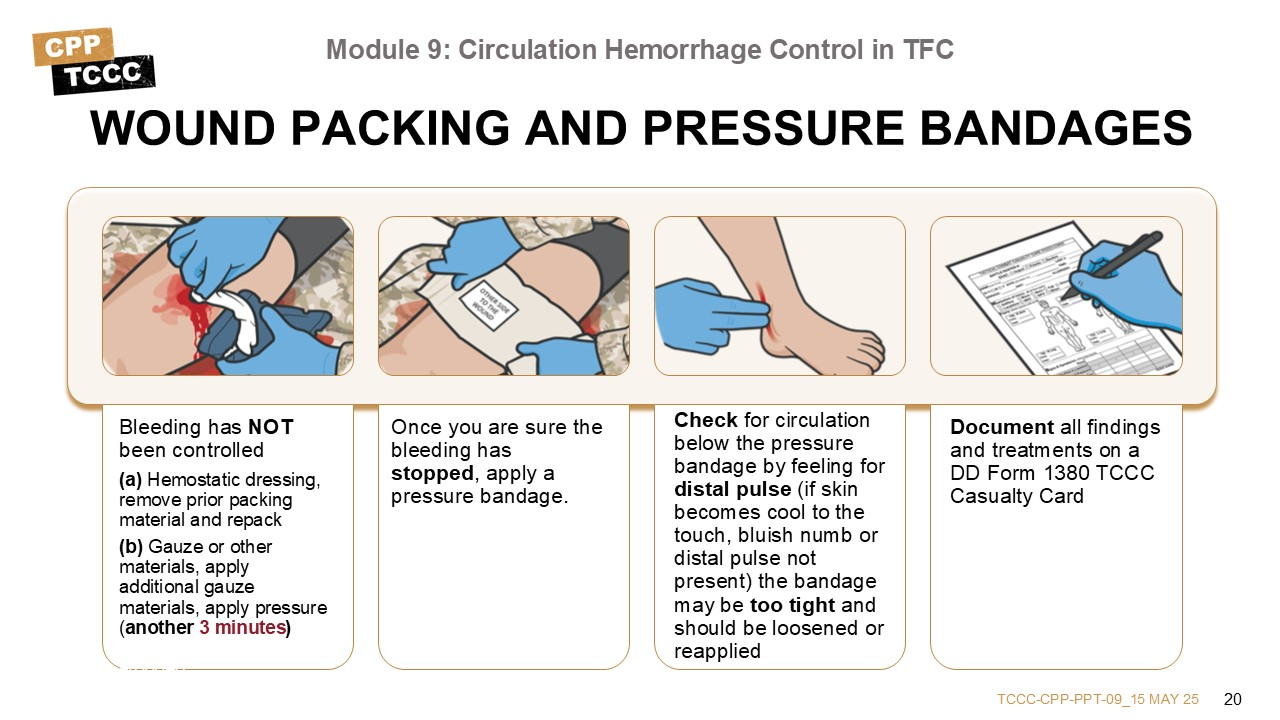

If Bleeding Has Not Been Controlled

- If packed with hemostatic dressing, remove prior packing material and repack starting at step 3.

- If packed with gauze or other materials, apply additional gauze/materials and pressure (for another 3 minutes) until bleeding has stopped.

All dressings for significant bleeding should be secured with a pressure bandage while maintaining pressure on the wound throughout the process of applying the pressure bandage.

Also, wound packing and pressure bandage application can be used at this stage for larger bleeding wounds that were not previously addressed, but that should be controlled prior to the wound phase (or the “W” of MARCH-PAWS).

This video will review the principles of wound packing and pressure bandage application.

WOUND PACKING & PRESSURE BANDAGES

The following skill cards will demonstrate and help you practice replacing tourniquets and converting tourniquets with wound packing and pressure bandages.

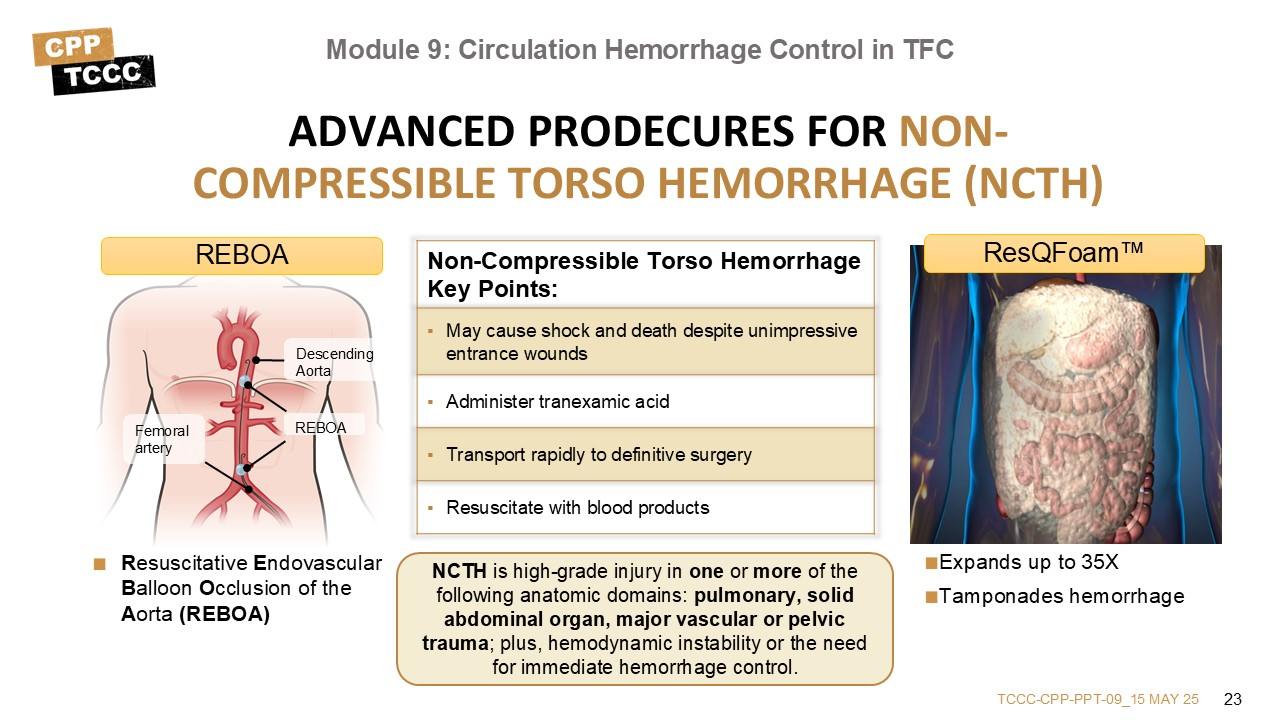

Another situation not discussed in the TCCC Guidelines that you may encounter as CPP-level providers is non-compressible torso hemorrhage (NCTH). This can be defined as high-grade injury present in one or more of the following anatomic domains: pulmonary, solid abdominal organ, major vascular or pelvic trauma; plus, hemodynamic instability or the need for immediate hemorrhage control.43 In these situations, the standard interventions for massive hemorrhage and circulation control that have been discussed do not have appreciable impact.44

NCTH may cause shock and death despite relatively unimpressive entrance wounds. Currently, the mainstays of treatment include administration of tranexamic acid (discussed in the next module), resuscitation with whole blood (which replaces losses, but does not affect ongoing continued losses), and rapid transportation to a facility where definitive surgical control of the hemorrhage can be achieved. Transport of a casualty with suspected NCTH should be accomplished on an emergent basis.45

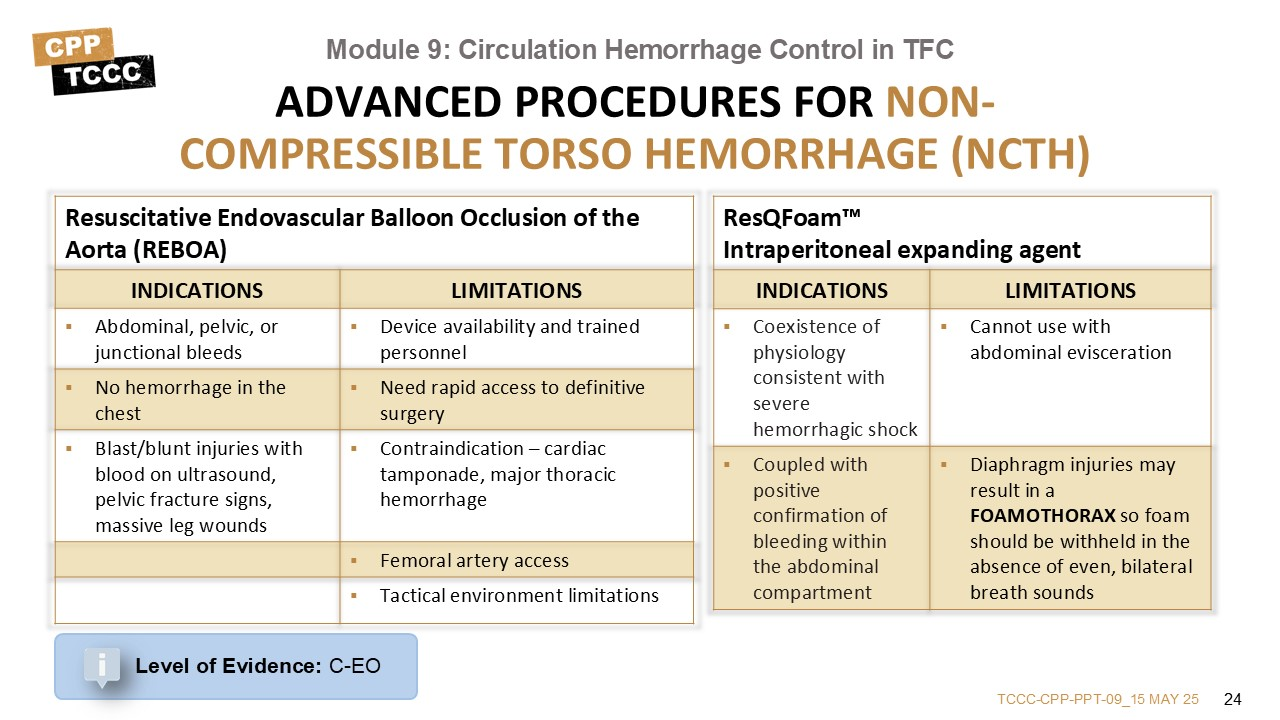

Two newer technologies that may assist with NCTH control are Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) and ResQFoam™, an intraperitoneally injected polyurethane self-expanding foam.46

REBOA hemorrhage control is a developing field with new information being published continuously, so the intent of this discussion is to introduce the concept, and understand its indications and limitations. For a more complete understanding of REBOA, refer to the JTS clinical practice guideline Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for Hemorrhagic Shock (CPG ID:38).47,48 REBOA can control NCTH using a less invasive option and with fewer physiologic disturbances compared with an invasive emergent thoracotomy for aortic cross-clamping.49

REBOA devices are inserted via the femoral artery, and consist of a catheter with an inflatable balloon. The catheter is passed retrograde up to the desired site of occlusion, and the balloon is inflated, stopping distal flow below the site of occlusion.50, 51 Traditionally, the procedure has been done mostly in medical treatment facilities under fluoroscopic guidance. But there have been use cases in more austere environments.52, 53, 54

Another situation not discussed in the TCCC Guidelines that you may encounter as CPP-level providers is non-compressible torso hemorrhage (NCTH). This can be defined as high-grade injury present in one or more of the following anatomic domains: pulmonary, solid abdominal organ, major vascular or pelvic trauma; plus, hemodynamic instability or the need for immediate hemorrhage control.55 In these situations, the standard interventions for massive hemorrhage and circulation control that have been discussed do not have appreciable impact.56

NCTH may cause shock and death despite relatively unimpressive entrance wounds. Currently, the mainstays of treatment include administration of tranexamic acid (discussed in the next module), resuscitation with whole blood (which replaces losses, but does not affect ongoing continued losses), and rapid transportation to a facility where definitive surgical control of the hemorrhage can be achieved. Transport of a casualty with suspected NCTH should be accomplished on an emergent basis.57

Two newer technologies that may assist with NCTH control are Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) and ResQFoam™, an intraperitoneally injected polyurethane self-expanding foam.58

REBOA hemorrhage control is a developing field with new information being published continuously, so the intent of this discussion is to introduce the concept, and understand its indications and limitations. For a more complete understanding of REBOA, refer to the JTS clinical practice guideline Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for Hemorrhagic Shock (CPG ID:38).59, 60 REBOA can control NCTH using a less invasive option and with fewer physiologic disturbances compared with an invasive emergent thoracotomy for aortic cross-clamping.61

REBOA devices are inserted via the femoral artery, and consist of a catheter with an inflatable balloon. The catheter is passed retrograde up to the desired site of occlusion, and the balloon is inflated, stopping distal flow below the site of occlusion.62, 63 Traditionally, the procedure has been done mostly in medical treatment facilities under fluoroscopic guidance. But there have been use cases in more austere environments.64, 65, 66

REBOA is indicated in casualties exsanguinating from abdominal, pelvic, or junctional lower extremity bleeding who are not in cardiopulmonary arrest, and do not have exsanguinating hemorrhage in the chest.67 This determination may be suspected based on the mechanism of injury to the abdomen or pelvis, a blast or blunt injury with a positive focused assessment with sonography in trauma or suspected pelvic fracture, or massive proximal lower extremity trauma with signs of impending cardiovascular collapse.

But REBOA has significant limitations. These include:

- A contraindication in the setting of major thoracic hemorrhage or pericardial tamponade68

- The need for expedient access to definitive hemorrhage control (depending on the anatomic location of the device, there are time limits before ischemic damage is likely, ranging from 30-60 minutes)69, 70

- REBOA availability and provider training/experience71

- Lack of femoral vascular access72

- Tactical limitations (scene safety, room to maneuver, mass casualty considerations, etc.)

The evidence supporting the use of REBOA comes from retrospective systematic reviews of descriptive and qualitative studies, as well as subject matter expert consensus statements.

ResQFoam is one of a handful of agents being investigated that expand in the abdomen and tamponade sources of internal hemorrhage. It involves mixing and percutaneously injecting two liquid precursors into the peritoneal cavity. The resulting compound rapidly expands approximately 35-fold inside the abdomen and becomes a solid foam that conforms to the anatomy of the abdominal organs over a one-minute period. It is designed not to adhere to the abdominal organs and tissues, allowing for easier removal at surgery.73

Currently, neither ResQFoam, nor any similar product, is FDA approved; but it has been FDA approved for use in human clinical trials after successful results in animal models.74, 75

There are potential advantages of an expanding agent that controlled internal hemorrhage by tamponade. A wider range of medical personnel could be trained to use this intervention when compared to those who could be trained to perform REBOA. It would likely be more accessible at forward locations. The fact that it does not completely occlude distal flow would allow for longer times between application and definitive surgery, allowing for it to be used even if surgery may be delayed.76

In general, the level of evidence for the interventions and information discussed in this module ranged from low to moderate. There were more studies about PCDs that focused on their functionality, but less focused on the added survival benefit, resulting in a low to moderate rating. Tourniquet replacements and conversions have more available data, although they, too, are less robust in defining the impact; but they both have a moderate level of supporting evidence. REBOA, although the level of data is increasing with time, currently maintains a low to moderate rating, while expandable intraperitoneal agents to tamponade hemorrhage are just now being explored with human clinical trials and the overall level of evidence remains low at this time.

This video will recap some of the important concepts of hemorrhage control during circulation management in TFC.

HEMORRHAGE CONTROL IN TFC

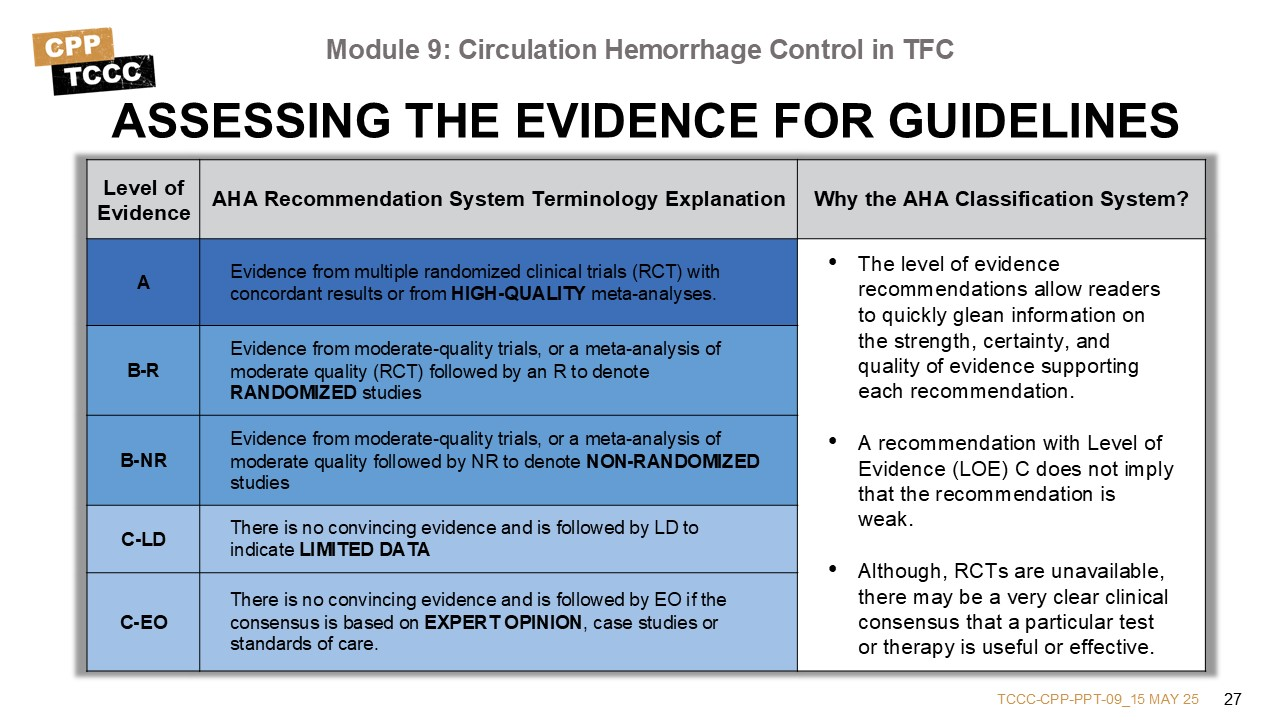

Evidence-based recommendations and guidance is the result of a careful review of studies and discussion by a panel of subject matter experts. For TCCC, the subject matter expert panels include both Committee on TCCC members and select invited subject matter experts from within both the military and civilian community, based on the specific interest area.

Why the AHA Classification System?

The level of evidence classification combines an objective description of the existence and the types of studies supporting the recommendation and expert consensus, according to 1 of the following 3 categories:77

- Level of evidence A: recommendation based on evidence from multiple randomized trials or meta-analyses

- Level of evidence B: recommendation based on evidence from a single randomized trial or nonrandomized studies

- Level of evidence C: recommendation based on expert opinion, case studies, or standards of care.

The level of evidence recommendations allows readers to quickly glean information on the strength, certainty, and quality of evidence supporting each recommendation. The Level of Evidence (LOE) denotes the confidence in or certainty of the evidence supporting the recommendation, based on the type, size, quality, and consistency of pertinent research findings.78

A recommendation with level of evidence C does not imply that the recommendation is weak. Many important clinical questions addressed in guidelines do not lend themselves to clinical trials. Although, Randomized Clinical Trials are unavailable, there may be a very clear clinical consensus that a particular test or therapy is useful or effective.

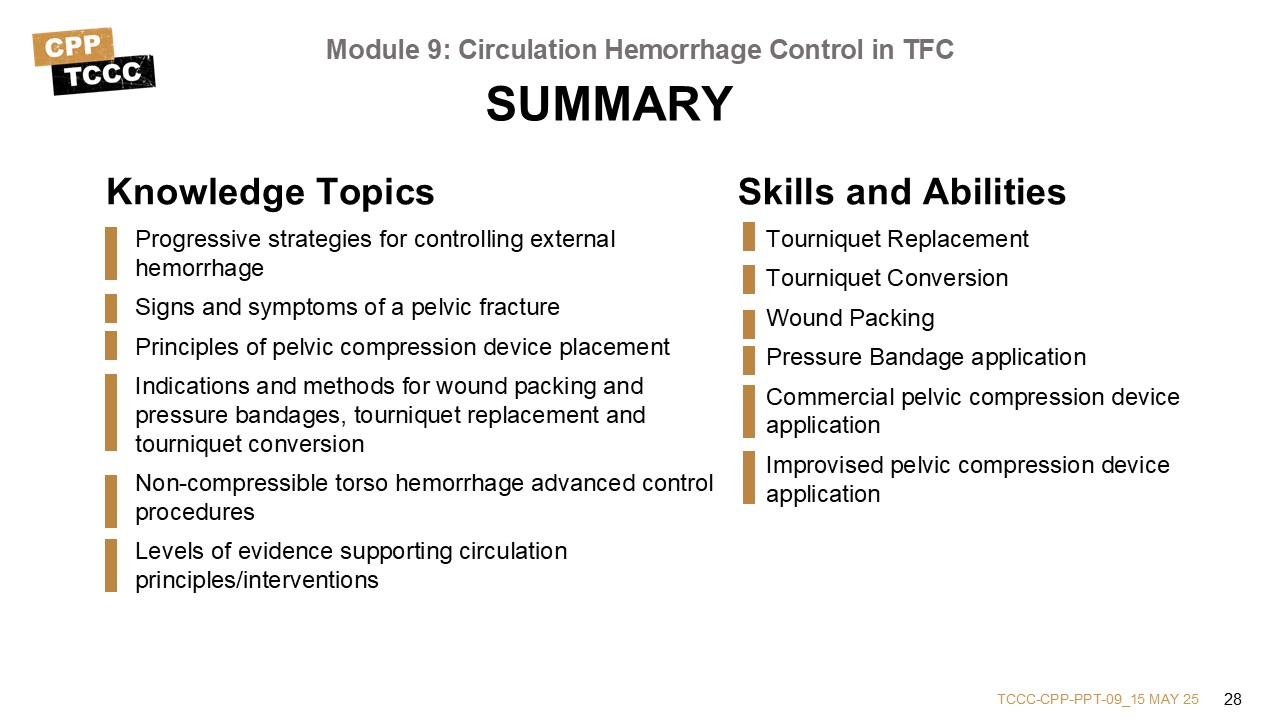

This first part of circulation management in TFC focuses on hemorrhage control. This includes:

- Identifying the progressive strategies for controlling external hemorrhage

- Identifying the signs and symptoms of a pelvic fracture

- Understanding the principles for PCD placement

- Identifying the indications and methods for wound packing and pressure bandages, tourniquet replacement, and tourniquet conversion

- Describing some of the advanced hemorrhage control procedures in non-compressible torso hemorrhage situations

- Understanding the level of evidence to support each intervention or principle.

The skills that were taught and practiced included the application of both commercial and improvised PCDs, wound packing and pressure bandage application, tourniquet replacement, and tourniquet conversion.

The next two modules will focus on other aspects of the circulation phase of the MARCH-PAWS sequence in the Tactical Field Care environment: recognition and management of shock, and hemorrhagic shock fluid resuscitation.

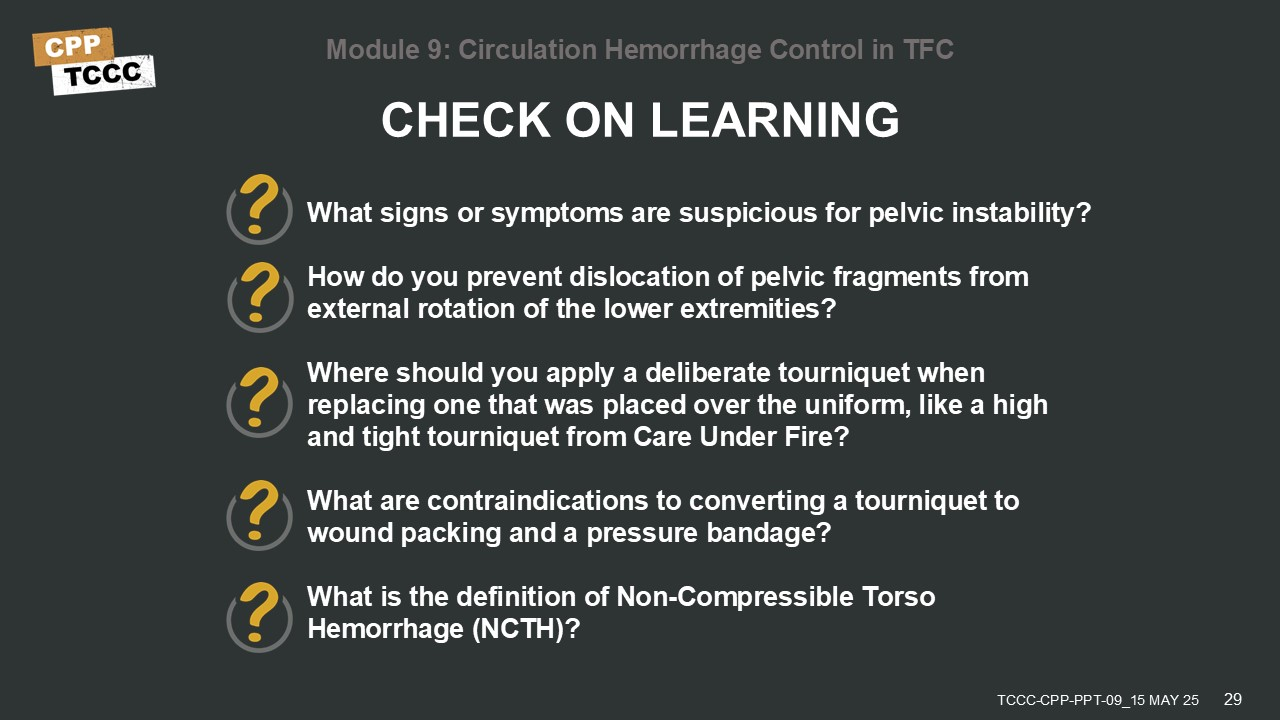

To close out this module, check your learning with the questions below (answers under the image).

Answers

What signs or symptoms are suspicious for pelvic instability?

- Pelvic pain, any major lower limb amputation or near amputation, physical exam findings suggestive of a pelvic fracture (for example, laceration or bruising at bony prominences of the pelvic ring, a deformed or unstable pelvis or unequal leg lengths), unconsciousness or shock with a mechanism of injury involving significant force, like an IED blast or MVA.

How do you prevent dislocation of pelvic fragments from external rotation of the lower extremities?

- Prevent external rotation of the lower extremities by tying the casualty’s knees and/or feet together.

Where should you apply a deliberate tourniquet when replacing one that was placed over the uniform, like a high and tight tourniquet from Care Under Fire?

- Place a replacement tourniquet directly on the skin, 2-3 inches above the wound.

What are contraindications to converting a tourniquet to wound packing and a pressure bandage?

- Amputation, tourniquet has been on for six or more hours, shock, inability to closely monitor the wound, if the casualty will arrive at a medical treatment facility within 2 hours or if tactical or medical considerations make conversion inadvisable.

What is the definition of Non-Compressible Torso Hemorrhage (NCTH)?

- Non-Compressible Torso Hemorrhage (NCTH) is high-grade injury in one or more of the following anatomic domains: pulmonary, solid abdominal organ, major vascular or pelvic trauma; plus, hemodynamic instability or the need for immediate hemorrhage control.

1 Montgomery, HR, et al. Tactical Combat Casualty Care Quick Reference Guideline, 1st Ed. 2017. Page 13. Available at https://deployedmedicine.com/market/11/content/87, accessed 15 Dec 21.

2 Davis JM, Stinner DJ, Bailey JR, et al. Factors associated with mortality in combat-related pelvic fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(suppl 1): S7–S12.

3 White CE, Hsu JR, Holcomb JB. Hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Injury. 2009;40: 1023–1030.

4 Bailey JR, Stinner DJ, Blackbourne LH, et al. Combat-related pelvis fractures in nonsurvivors. J Trauma 2011;71: S58–S61.

5 Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 December 2021, para 6.a. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 15 Dec 21.

6 Davis DD, Foris LA, Kane SM, et al. Pelvic Fracture. [Updated 2021 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430734/, accessed 15 Dec 21.

7 Shlamovitz G.Z., Mower W.R., Bergman J. How (un)useful is the pelvic ring stability examination in diagnosing mechanically unstable pelvic fractures in blunt trauma patients? J Trauma. 2009;66(3): 815–820.

8 Halawi MJ. Pelvic ring injuries: Emergency assessment and management. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6(4): 252-258.

9 Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 December 2021, para 6.a. https://deployedmedicine.com/market/31/content/40, accessed 15 Dec 21.

10 Knops SP, Schep NWL, Spoor CW, et al. Comparison of three different pelvic circumferential compression devices: a biomechanical cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93: 230–240.

11 DeAngelis NA, Wixted JJ, Drew J, et al. Use of the trauma pelvic orthotic device (T-POD) for provisional stabilization of anterior-posterior compression type pelvic fractures: a cadaveric study. Injury. 2008;39: 903–906.

12 Bryson DJ, Davidson R, Mackenzie R. Pelvic circumferential compression devices (PCCDs): a best evidence equipment review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2012;38: 439–442.

13 Bonner TJ, Eardley WG, Newell N, Masouros S, Matthews JJ, Gibb I, Clasper JC. Accurate placement of a pelvic binder improves reduction of unstable fractures of the pelvic ring. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 Nov;93(11): 1524-8.

14 Kuner V, van Veelen N, Studer S, Van de Wall B, Fornaro J, Stickel M, Knobe M, Babst R, Beeres FJP, Link BC. Application of Pelvic Circumferential Compression Devices in Pelvic Ring Fractures-Are Guidelines Followed in Daily Practice? J Clin Med. 2021 Mar 21;10(6): 1297.

15 Gardner MJ, Parada S, Chip Routt ML Jr. Internal rotation and taping of the lower extremities for closed pelvic reduction. J Orthop Trauma. 2009 May-Jun;23(5): 361-4.

16 Shackelford S, Hammesfahr R, Morissette D, Montgomery HR, Kerr W, Broussard M, Bennett BL, Dorlac WC, Bree S, Butler FK. The Use of Pelvic Binders in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 1602 7 November 2016. J Spec Oper Med. 2017 Spring;17(1): 135-147.

17 Routt MLC, Falicov A, Woodhouse E, et al. Circumferential pelvic antishock sheeting: a temporary resuscitation aid. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16: 45–48.

18 Prasarn ML, Conrad B, Small J, et al. Comparison of circumferential pelvic sheeting versus the T-POD on unstable pelvic injuries: a cadaveric study of stability. Injury. 2013;44: 1756–1759.

19 Nunn T, Cosker TDA, Bose D, et al. Immediate application of improvised pelvic binder as first step in extended resuscitation from life-threatening hypovolemic shock in conscious patients with unstable pelvic injuries. Injury. 2007;38: 125–128.

20 Bailey RA, Simon EM, Kreiner A, Powers D, Baker L, Giles C, Sweet R, Rush SC. Commercial and Improvised Pelvic Compression Devices: Applied Force and Implications for Hemorrhage Control. J Spec Oper Med. 2021 Spring;21(1): 44-48.

21 Improvised Pelvic Compression Device Instruction. Combat Medic/Corpsman Tactical Combat Casualty Care Skill Instructions. Module 9. 23 Jan 2021.

22 Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 9th Edition, Military Edition. Chapter 25, p 798.

23 Lee C, Porter KM, Hodgetts TJ. Tourniquet use in the civilian prehospital setting. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(8): 584-587.

24 Applying a Tourniquet. Stop the Bleed. Department of Homeland Security. Available at https://www.amr.net/about/medicine/stopthebleed/stb-wound-packing-applying-tourniquet.pdf, accessed 15 Dec 21.

25 Phillips R, Friberg M, Lantz Cronqvist M, Jonson C-O, Prytz E (2020) Visual estimates of blood loss by medical laypeople: Effects of blood loss volume, victim gender, and perspective. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0242096.

26 Phillips R, Friberg M, Lantz Cronqvist M, Jonson C-O, Prytz E. Visual Blood Loss Estimation Accuracy: Directions for Future Research Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 2020;64(1): 1411-1415.

27 Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 9th Edition, Military Edition. Chapter 25, p 798.

28 Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 9th Edition, Military Edition. Chapter 25, p 798.

29 Shackelford SA, Butler FK, Kragh JF, et al. Optimizing the use of Limb Tourniquets in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 14-02. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15: 17-31.

30 Dayan L, Zinmann C, Stahl S, Norman D. Complications Associated with Prolonged Tourniquet Application on the Battlefield. Military Medicine. Volume 173, Issue 1, January 2008: Pages 63–66.

31 Drew B, Bird D, Matteucci M, Keenan S. Tourniquet Conversion: A Recommended Approach in the Prolonged Field Care Setting. J Spec Oper Med. 2015 Fall;15(3): 81-5.

32 Drew B, Bird D, Matteucci M, Keenan S. Tourniquet Conversion: A Recommended Approach in the Prolonged Field Care Setting. J Spec Oper Med. 2015 Fall;15(3): 82-3, Figures 1-7.

33 Tourniquet Conversion Instruction. Combat Medic/Corpsman Tactical Combat Casualty Care Skill Instructions. Module 9. 23 Jan 2021.

34 Walters TJ, Mabry RL. Issues related to the use of tourniquets on the battlefield. Mil Med. 2005; 170: 770–775.

35 Drew B, Bird D, Matteucci M, Keenan S. Tourniquet Conversion: A Recommended Approach in the Prolonged Field Care Setting. J Spec Oper Med. 2015 Fall;15(3): 82.

36 Shackelford SA, Butler FK, Kragh JF, et al. Optimizing the use of Limb Tourniquets in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 14-02. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15: 17-31.

37 Dayan L, Zinmann C, Stahl S, Norman D. Complications Associated with Prolonged Tourniquet Application on the Battlefield. Military Medicine. Volume 173, Issue 1, January 2008: Pages 63–66

38 Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 9th Edition, Military Edition. Chapter 25, p 798.

39 Hemostatic Dressings and Devices. TCCC Recommended Devices and Adjuncts. Available at https://books.allogy.com/web/tenant/8/books/f94aad5b-78f3-42be-b3de-8e8d63343866/#id4e06a027-d62f-4928-9e3b-912491b17dab, accessed 16 Dec 21.

40 Bennett BL, Littlejohn LF, Kheirabadi BS, Butler FK, Kotwal RS, Dubick MA, Bailey JA. Management of External Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: Chitosan-Based Hemostatic Gauze Dressings--TCCC Guidelines-Change 13-05. J Spec Oper Med. 2014 Fall;14(3): 40-57.

41 Tactical Combat Casualty Care Guidelines, 15 December 2021, para 3.b. (missing Link)

42 Wound Packing and Pressure Bandage Instruction. Massive Hemorrhage Control in TFC Skill Instructions. Tactical Combat Casualty Care Course for Combat Lifesavers, Module 6. Available at https://learning-media.allogy.com/api/v1/pdf/5b775216-5bdd-48ae-b21d-4a55dd40b915/contents, accessed 16 Dec 21.

55 Morrison JJ. Noncompressible Torso Hemorrhage. Crit Care Clin. 2017 Jan;33(1): 37-54.

56 Morrison JJ, Rasmussen TE. Noncompressible torso hemorrhage: a review with contemporary definitions and management strategies. Surg Clin North Am. 2012 Aug;92(4): 843-58.

57 Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 9th Edition, Military Edition. Chapter 25, p 801.

58 Butler F, Blackbourne L, Gross KL. The Combat Medic Aid Bag: 2025 - CoTCCC Top 10 recommended battlefield trauma care research, development, and evaluation priorities for 2015. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15: 7-19.

59 Cannon J, Morrison J, Lauer C, Grabo D, Polk T, Blackbourne L, Dubose J, Rasmussen T. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for Hemorrhagic Shock. Mil Med. 2018 Sep 1;183(suppl_2): 55-59.

60 Glaser J, et al. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for Hemorrhagic Shock (CPG ID:38). Joint Trauma System Clinical Practice Guideline. 31 Mar 2020. Available at https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Resuscitative_Endovascular_Balloon_Occlusion_of_the_Aorta_(REBOA)_for_Hemorrhagic_Shock_31_Mar_2020_ID38.pdf, accessed 16 Dec 21.

61 Ribeiro J, Maurício AD, Costa CTK, Néder PR, Augusto SS, Di-Saverio S, Brenner M. Expanding indications and results for the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta - REBOA. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2019 Dec 20;46(5): e20192334.

62 Rasmussen T, Eliason J. Military-civilian partnership in device innovation: development, commercial and application of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Oct;83(4): 732-735.

63 DuBose J, Scalea T, Brenner M, et al. The AAST prospective aortic occlusion for resuscitation in trauma and acute care surgery (AORTA) registry: data on contemporary utilization and outcomes of aortic occlusion and resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81: 409-419.

64 Manley J, Mitchell B, DuBose J, Rasmussen T. A modern case series of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in an out-of-hospital, combat casualty care setting. J Spec Oper Med. 2017;17: 1-8.

65 Stokes SC, Theodorou CM, Zakaluzny SA, DuBose JJ, Russo RM. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in combat casualties: The past, present, and future. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021 Aug 1;91(2S Suppl 2): S56-S64.

66 Stannard A, Morrison JJ, Scott DJ, et al. The epidemiology of noncompressible torso hemorrhage in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74(3): 830–4.

67 Glaser J, et al. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for Hemorrhagic Shock (CPG ID:38). Joint Trauma System Clinical Practice Guideline. 31 Mar 2020. Available at https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Resuscitative_Endovascular_Balloon_Occlusion_of_the_Aorta_(REBOA)_for_Hemorrhagic_Shock_31_Mar_2020_ID38.pdf, accessed 16 Dec 21.

68 Inoue J, Shiraishi A, Yoshiyuki A, Haruta K, Matsui H, Otomo Y. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta might be dangerous in patients with severe torso trauma: A propensity score analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016;80: 559-567.

69 Reva VA, Matsumura Y, Hörer T, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta: what is the optimum occlusion time in an ovine model of hemorrhagic shock? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018 Aug;44(4): 511-518.

70 Glaser J, et al. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for Hemorrhagic Shock (CPG ID:38). Joint Trauma System Clinical Practice Guideline. 31 Mar 2020. Available at https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Resuscitative_Endovascular_Balloon_Occlusion_of_the_Aorta_(REBOA)_for_Hemorrhagic_Shock_31_Mar_2020_ID38.pdf, accessed 16 Dec 21.

71 Northern DM, Manley JD, Lyon R, et al. Recent advances in austere combat surgery: Use of aortic balloon occlusion as well as blood challenges by special operations medical forces in recent combat operations. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018 Jul;85(1S Suppl 2): S98-S103

72 Marquis-Gravel G1, Tremblay-Gravel M1, Lévesque J1, Généreux P1,2,3, Schampaert E1, Palisaitis D1, Doucet M1, Charron T1, Terriault P1, Tessier P1. Ultrasound guidance versus anatomical landmark approach for femoral artery access in coronary angiography: A randomized controlled trial and a meta-analysis. J Interv Cardiol. 2018 Aug;31(4): 496-503.

73 Chang J, Holloway B, Zamisch M, Hepburn MJ, Ling GS. ResQFoam for the treatment on non-compressible hemorrhage on the front line. Mil Med. 2015;180(9):932-933.

74 Rago A, Duggan M, Marini J, et al. Self-expanding foam improves survival following a lethal, exsanguinating iliac artery injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77: 73-77.

75 Rago A, Marini J, Duggan M, et al. Diagnosis and deployment of a self-expanding foam for abdominal exsanguination: translation questions for human use. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015; 2015:78: 607-613

76 Prehospital Trauma Life Support, 9th Edition, Military Edition. Chapter 25, p 802.

77 Tricoci P, Allen JM, Kramer JM, Califf RM, Smith Jr SC. Scientific Evidence Underlying the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Medical Association. 2009 Feb; Vol 301, No. 8.

78 Halparin, JL. Further Evolution of the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendation Classification System. American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. 2016 Apr; 133:1426-1428.

Evidence Based References:

Bailey JR, Stinner DJ, Blackbourne LH, et al. Combat-related pelvis fractures in non-survivors. J Trauma 2011;71: S58–S61 B-NR

Bailey RA, Simon EM, Kreiner A, Powers D, Baker L, Giles C, Sweet R, Rush SC. Commercial and Improvised Pelvic Compression Devices: Applied Force and Implications for Hemorrhage Control. J Spec Oper Med. 2021 Spring;21(1): 44-48 C-LD

Bennett BL, Littlejohn LF, Kheirabadi BS, Butler FK, Kotwal RS, Dubick MA, Bailey JA. Management of External Hemorrhage in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: Chitosan-Based Hemostatic Gauze Dressings--TCCC Guidelines-Change 13-05. J Spec Oper Med. 2014 Fall;14(3): 40-57 C-LD

Bonner TJ, Eardley WG, Newell N, Masouros S, Matthews JJ, Gibb I, Clasper JC. Accurate placement of a pelvic binder improves reduction of unstable fractures of the pelvic ring. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011 Nov;93(11): 1524-8 B-NR

Bryson DJ, Davidson R, Mackenzie R. Pelvic circumferential compression devices (PCCDs): a best evidence equipment review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2012;38: 439–442 C-LD

Butler F, Blackbourne L, Gross KL. The Combat Medic Aid Bag: 2025 - CoTCCC Top 10 recommended battlefield trauma care research, development, and evaluation priorities for 2015. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15: 7-19 C-EO

Cannon J, Morrison J, Lauer C, Grabo D, Polk T, Blackbourne L, Dubose J, Rasmussen T. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta (REBOA) for Hemorrhagic Shock. Mil Med. 2018 Sep 1;183(suppl_2): 55-59 C-EO

Chang J, Holloway B, Zamisch M, Hepburn MJ, Ling GS. ResQFoam for the treatment on non-compressible hemorrhage on the front line. Mil Med. 2015;180(9):932-933 C-EO

Davis JM, Stinner DJ, Bailey JR, et al. Factors associated with mortality in combat-related pelvic fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(suppl 1): S7–S12 B-NR

Dayan L, Zinmann C, Stahl S, Norman D. Complications Associated with Prolonged Tourniquet Application on the Battlefield. Military Medicine. Volume 173, Issue 1, January 2008: Pages 63–66 C-EO

DeAngelis NA, Wixted JJ, Drew J, et al. Use of the trauma pelvic orthotic device (T-POD) for provisional stabilization of anterior-posterior compression type pelvic fractures: a cadaveric study. Injury. 2008;39: 903–906 C-LD

Drew B, Bird D, Matteucci M, Keenan S. Tourniquet Conversion: A Recommended Approach in the Prolonged Field Care Setting. J Spec Oper Med. 2015 Fall;15(3): 81-5 C-EO

DuBose J, Scalea T, Brenner M, et al. The AAST prospective aortic occlusion for resuscitation in trauma and acute care surgery (AORTA) registry: data on contemporary utilization and outcomes of aortic occlusion and resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81: 409-419 B-NR

Gardner MJ, Parada S, Chip Routt ML Jr. Internal rotation and taping of the lower extremities for closed pelvic reduction. J Orthop Trauma. 2009 May-Jun;23(5): 361-4 C-EO

Halawi MJ. Pelvic ring injuries: Emergency assessment and management. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6(4): 252-258 C-EO

Improvised Pelvic Compression Device Instruction. Combat Medic/Corpsman Tactical Combat Casualty Care Skill Instructions. Module 9. 23 Jan 2021 Tier 3

Inoue J, Shiraishi A, Yoshiyuki A, Haruta K, Matsui H, Otomo Y. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta might be dangerous in patients with severe torso trauma: A propensity score analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016;80: 559-567 B-NR

Kam PC, Kavanagh R, Yoong FF. The arterial tourniquet: pathophysiological consequences and anesthetic implications. Anaesthesia. 2001;56: 534–545 C-EO

Klenerman L. Tourniquet time—how long? Hand. 1980;12: 231–234 C-EO

Kragh JF Jr, Baer DG, Walters TJ. Extended (16-hour) tourniquet application after combat wounds: a case report and review of current literature. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21: 274–278 C-LD

Kragh JF Jr, O'Neill ML, Walters TJ, Jones JA, Baer DG, Gershman LK, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Minor morbidity with emergency tourniquet use to stop bleeding in severe limb trauma: research, history, and reconciling advocates and abolitionists. Mil Med. 2011;176(7): 817–23 B-NR

Kragh JF, Walters TJ, Baer DG, et al. Practical use of emergency tourniquets to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64(2) (suppl): S38-S49 B-NR

Kuner V, van Veelen N, Studer S, Van de Wall B, Fornaro J, Stickel M, Knobe M, Babst R, Beeres FJP, Link BC. Application of Pelvic Circumferential Compression Devices in Pelvic Ring Fractures-Are Guidelines Followed in Daily Practice? J Clin Med. 2021 Mar 21;10(6): 1297 B-NR

Lee C, Porter KM, Hodgetts TJ. Tourniquet use in the civilian prehospital setting. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(8): 584-587 C-EO

Manley J, Mitchell B, DuBose J, Rasmussen T. A modern case series of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in an out-of-hospital, combat casualty care setting. J Spec Oper Med. 2017;17: 1-8 B-NR

Marquis-Gravel G1, Tremblay-Gravel M1, Lévesque J1, Généreux P1,2,3, Schampaert E1, Palisaitis D1, Doucet M1, Charron T1, Terriault P1, Tessier P1. Ultrasound guidance versus anatomical landmark approach for femoral artery access in coronary angiography: A randomized controlled trial and a meta-analysis. J Interv Cardiol. 2018 Aug;31(4): 496-503 B-R

Morrison JJ, Rasmussen TE. Noncompressible torso hemorrhage: a review with contemporary definitions and management strategies. Surg Clin North Am. 2012 Aug;92(4): 843-58 C-EO

Morrison JJ. Noncompressible Torso Hemorrhage. Crit Care Clin. 2017 Jan;33(1): 37-54 C-EO

Northern DM, Manley JD, Lyon R, et al. Recent advances in austere combat surgery: Use of aortic balloon occlusion as well as blood challenges by special operations medical forces in recent combat operations. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018 Jul;85(1S Suppl 2): S98-S103 C-EO

Nunn T, Cosker TDA, Bose D, et al. Immediate application of improvised pelvic binder as first step in extended resuscitation from life-threatening hypovolemic shock in conscious patients with unstable pelvic injuries. Injury. 2007;38: 125–128 C-EO

Phillips R, Friberg M, Lantz Cronqvist M, Jonson C-O, Prytz E (2020) Visual estimates of blood loss by medical laypeople: Effects of blood loss volume, victim gender, and perspective. PLoS ONE 15(11): e0242096 C-LD

Phillips R, Friberg M, Lantz Cronqvist M, Jonson C-O, Prytz E. Visual Blood Loss Estimation Accuracy: Directions for Future Research Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 2020;64(1): 1411-1415

Prasarn ML, Conrad B, Small J, et al. Comparison of circumferential pelvic sheeting versus the T-POD on unstable pelvic injuries: a cadaveric study of stability. Injury. 2013;44: 1756–1759 C-LD

Rago A, Duggan M, Marini J, et al. Self-expanding foam improves survival following a lethal, exsanguinating iliac artery injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77: 73-77 C-LD

Rago A, Marini J, Duggan M, et al. Diagnosis and deployment of a self-expanding foam for abdominal exsanguination: translation questions for human use. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015; 2015:78: 607-613 C-LD

Rasmussen T, Eliason J. Military-civilian partnership in device innovation: development, commercial and application of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Oct;83(4): 732-735 C-EO

Reva VA, Matsumura Y, Hörer T, et al. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta: what is the optimum occlusion time in an ovine model of hemorrhagic shock? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018 Aug;44(4): 511-518 C-LD

Ribeiro J, Maurício AD, Costa CTK, Néder PR, Augusto SS, Di-Saverio S, Brenner M. Expanding indications and results for the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta - REBOA. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2019 Dec 20;46(5): e20192334 C-EO

Routt MLC, Falicov A, Woodhouse E, et al. Circumferential pelvic antishock sheeting: a temporary resuscitation aid. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16: 45–48 C-EO

Shackelford S, Hammesfahr R, Morissette D, Montgomery HR, Kerr W, Broussard M, Bennett BL, Dorlac WC, Bree S, Butler FK. The Use of Pelvic Binders in Tactical Combat Casualty Care: TCCC Guidelines Change 1602 7 November 2016. J Spec Oper Med. 2017 Spring;17(1): 135-147 C-EO

Shlamovitz G.Z., Mower W.R., Bergman J. How (un)useful is the pelvic ring stability examination in diagnosing mechanically unstable pelvic fractures in blunt trauma patients? J Trauma. 2009;66(3): 815–820 B-NR

Stannard A, Morrison JJ, Scott DJ, et al. The epidemiology of noncompressible torso hemorrhage in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74(3): 830–4 B-NR

Stokes SC, Theodorou CM, Zakaluzny SA, DuBose JJ, Russo RM. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in combat casualties: The past, present, and future. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021 Aug 1;91(2S Suppl 2): S56-S64 C-EO

Walters TJ, Mabry RL. Issues related to the use of tourniquets on the battlefield. Mil Med. 2005 Sep;170(9):770-5. doi: 10.7205/milmed.170.9.770. PMID: 16261982. C-EO

White CE, Hsu JR, Holcomb JB. Hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Injury. 2009;40: 1023–1030 C-EO

C-EO