Traumatic Brain Injury Management and Basic Neurosurgery in the Deployed Environment

Joint Trauma System

Traumatic Brain Injury Management and Basic Neurosurgery in the Deployed Environment

Summary of Changes

- Clarification of the use of the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation 2 (MACE2) for mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI).

- Clarification of the use of hypertonic saline or normal saline during resuscitation.

- Addition of the recommendation to use quantitative pupillometry for evaluation of pupillary reactivity.

- Addition of recommendation for Ketamine as a sedative in severe TBI.

- Addition of recommendation for tranexamic acid (TXA).

- Addition of recommendations to consider placement of Brain Tissue Oxygen Monitor (PbtO2) and maintaining > 20mmHg.

- Addition of recommendation for vascular imaging of penetrating brain injuries to rule out traumatic pseudoaneurysms.

- Changed seizure prophylaxis for TBI to make Levetiracetam the preferred agent and dilantin a third line agent given the inability to obtain drug levels in austere environments. Added in Vimpat as a second line agent for seizure prophylaxis.

- Addition of treatment algorithms for treating elevated intracranial pressure, decreased PbtO2, or both.

PURPOSE

These guidelines are not intended to supplant physician judgment. Rather, these guidelines are intended to provide a basic framework for those less experienced with the delivery of care in this setting to the brain injured patient, as well as to educate and provide insight to others on the delivery of care in a restrictive environment.

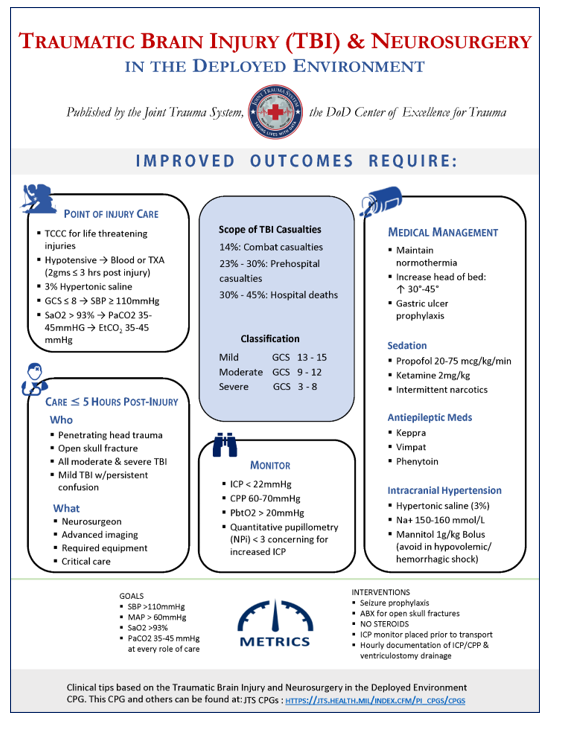

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) occurs in about one third of all trauma-related deaths in the United States and remains one of the most common causes of death on the modern battlefield.1,2 The Committee on Surgical Combat Casualty Care (CoSCCC) published a Neurosurgical Capabilities Position Statement in Feb 2023 given the importance of this issue. Specific to the combat environment:

- Positive outcomes are achieved through point of injury care to prevent secondary brain injury (avoid hypoxia, avoid hypotension), rapid evacuation from the battlefield, early medical management, timely neurosurgical intervention, meticulous critical care, and dedicated rehabilitation.3-9

- Optimal outcomes for severe TBI (Glasgow Coma Score [GCS] </=8) in theatre require a neurosurgical capability defined as a neurosurgeon, advanced imaging, required surgical sets, required monitoring, and critical care.

- For conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, Department of Defense Trauma Registry (DoDTR) data demonstrate: 10,11

- 14% of casualties sustained a traumatic brain injury.10

- TBI was the mechanism of death for 30% of prehospital deaths from 2001 to 2011 and 45% of hospital deaths from 2001 to 2009.12

- From 2014 to 2021 Armed Forces Medical Examiner System (AFMES) data demonstrate TBI accounted for 23% of prehospital deaths and 30% of hospital deaths (Unpublished JTS-AFMES data).

- Over 5,600 neurosurgical procedures were performed in-theater between 2002-2016.12

- Casualties with a TBI and an indication for neurosurgical intervention were more likely to survive if they received surgery within 5 hours of injury.9

- Neurosurgical interventions performed on the battlefield after penetrating injuries result in improved survival.13

- Severe TBI also occurs during routine and crisis contingency operations, both ground and maritime combat, with an associated mortality of 69.7%.

- The incidence of TBI after non-combat maritime mass casualty events such as collisions is 5.8%; during modern naval warfare when warships are attacked by missile strikes or other explosive devices, the incidence of severe TBI is 17.2%.14

- Some patients with severe closed and penetrating brain injury had favorable outcomes when treated in military medical treatment facilities (MTFs) and received timely and aggressive neurosurgical and neuro-critical care interventions.2-5,9

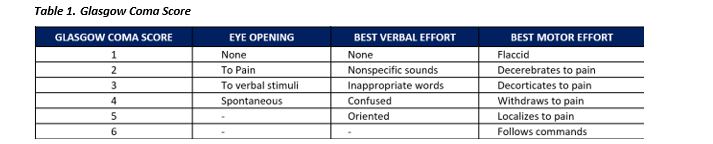

The classification of brain injury informs prognosis and care eligibility in the combat environment. Brain injury severity is classified according to their GCS.

- Mild: GCS 13-15

- Moderate: GCS 9-12

- Severe: GCS 3-8

Neurosurgical care capabilities are available at designated Role 3 facilities, Role 4 facilities and in pre-identified partner nation facilities.

Role 3 Transfer For Neurosurgical Evaluation & Care

Neurosurgical care in a combat theater is a limited resource and often requires air transport to get patients to the closest neurosurgeon or even Computed Tomography (CT) for diagnosis and treatment. Both over- and under-utilization should be avoided.

- Coalition casualties may require transfer for formal evaluation with a CT scan and/or a neurosurgeon when they:

- continue to have a GCS < 14 (mild TBI needs further evaluation in coalition casualties if the GCS does not return to GCS of 15).

- are confused or have continued cognitive deficits.

- The MACE2 is validated for determining the presence of an mTBI and should be used as an initial screening tool for to evaluate mTBI. It should not be used to determine worsening intracranial injury.15-17

- All coalition casualties should be referred for neurosurgical evaluation if they have:

- Management of host nation casualties should be in accordance with medical rules of eligibility (MEDROE) established for the area of responsibility. TBI management and neurosurgical care of HN casualties are MEDROE dependent. Providers should care to the best of their capabilities for HN TBI patients and involve the theater Trauma Medical Director (TMD) and neurosurgery (NS) early in the management.

- When MEDROE permits, moderate brain injury in HN casualties should be referred to Role 3 facilities with neurosurgical capability for definitive care.

- All patients should ethically receive equal care; however, the realities of combat are that HN casualties with severe brain injury have a poor prognosis when follow-on care is not available after discharge from the military MTF. The decision to transfer HN casualties with severe brain injury to Role 3 is based on mission, tactical situation, and resource availability and is ideally preceded by direct communication and discussion with the TMD and neurosurgeon.

- Depending on the severity of TBI, considerations for transfer of HN casualties to HN facilities after Role 3 MTF care can be complicated, multifactorial, and dependent on current MEDROEs. HN patients may not receive optimal care after leaving the military MTF, which adds to the complexity of decision-making for the care of these patients. For patients with severe TBI and poor prognosis, palliative care at the in-theatre MTF may be most appropriate. These decisions should be made in the context of TBI severity and the available continuum of care for the patient in their nation of origin. Discussions with the theater neurosurgeon, TMD, and command elements can aid in this difficult decision.

Early Evaluation and Treatment

The initial management of the patient with brain trauma begins with addressing life-threatening injuries and resuscitation in accordance with Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines in the field for corpsmen and combat medics or Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) providers.18

- 3% NaCl 250cc over 15 min

- Antiepileptics (Keppra 1500mg IV loading dose)

- TXA 2gm (if < 3 hours post-injury)

- Antibiotics if open skull fracture

- Simple physical interventions to implement early:

- Head of bed elevated to 30-45 degrees or reverse Trendelenburg (if in spinal precautions)

- Keep head straight to avoid kinking of the internal jugular veins (to promote venous drainage)

- Avoid tight cervical collars and tight circumferential endotracheal tube/tracheostomy tube ties

- Imaging: Patients with a suspected traumatic brain injury with altered mental status (GCS 12 or less) should have a non-contrast head CT as soon as possible. For penetrating head injuries, in addition to the non-contrast head CT study, a CT angiogram of the brain should also be obtained to evaluate for vascular injuries (e.g., pseudoaneurysms).

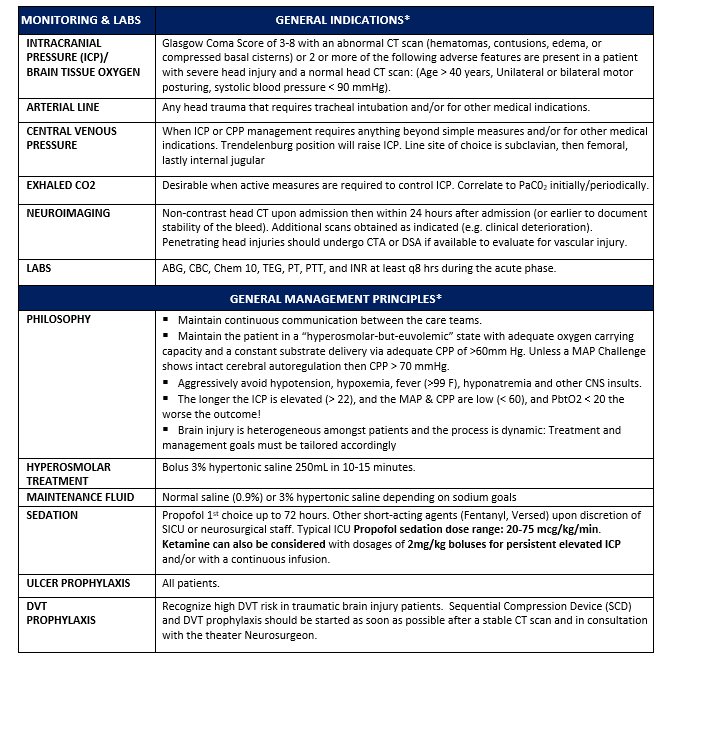

- Blood products are the preferred resuscitative fluid for hypotension in all trauma patients. Avoid Albumin and hydroxyethyl starches; albumin is associated with worse outcomes when used in TBI patients.19,20

- Tranexamic acid: All patients with evidence of moderate or severe TBI should be administered 2gm of TXA within 3hrs of injury; 2gm of TXA in TBI patients improves survival.21,

- If severe TBI is suspected, antiepileptics (Keppra, 1500 mg loading dose) should be administered during the initial evaluation and within 30 minutes of arrival.

- For casualties with abnormal GCS who do not require resuscitation for hypotension or major blood loss, use normal saline or 3% hypertonic saline for volume resuscitation. Both have shown equivalent outcomes in severe TBI. Avoid hypotonic fluids (e.g., any IVF with Dextrose % in water [D5W]).

- For casualties with GCS ≤ 8, manage hypotension by maintaining systolic blood pressure greater than 110 mmHg.22 A systolic blood pressure of less than 90mmHg is the single risk factor most highly associated with mortality in brain trauma.23,24

- End tidal CO2 (EtCO2) should be monitored during prehospital care and continued after handoff to a surgical team. Normoventilation with a goal partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) of 35-45mmHg should be maintained or EtCO2 of 35-45 mmHg. DO NOT hyperventilate.

- Prophylactic hyperventilation is not recommended as it decreases cerebral blood flow. It may be used as a temporizing measure to reduce intracranial pressure in the setting of suspected herniation until other therapies are employed to decrease intracranial pressure as the patient is on the way to the operating room.25 Hyperventilation can be harmful. 22

- For penetrating brain injuries and open skull fractures, routine prophylactic antibiotics are indicated.26 Antibiotic recommendations for the first level of surgical care include either cefazolin 2gm IV every 6-8 hours or clindamycin 600mg IV every 8 hours. If a penetrating head injury appears grossly contaminated with organic debris, consider addition of metronidazole 500mg IV every 8-12 hours.26

- For isolated closed head injuries, routine prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated.

- Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia must be avoided. Monitor glucose every 6 hours. The goal is to maintain glucose < 180 mg/dl and avoid hypoglycemia.27 D5W IVF will worsen cerebral edema. Do NOT use intravenously to maintain euglycemia.

- Steroids should be avoided in brain-injured patients as they have not shown outcome benefit and increase mortality in patients with severe brain injury.25,28

- A common strategy for management of hypoxemia has been a goal of arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) >90% and the partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood (PaO2) >60 mmHg.24 However, in order to establish a safety buffer in the deployed setting often characterized by frequent patient handoffs and occasional equipment challenges, a goal SaO2 of 93% and PaO2 >80mmHg, is recommended. Particular attention to avoidance of hypoxemia during air transport is essential as human studies and animal models indicate hypoxia during aeromedical evacuation is common.29,30

- Document serial neurological exam findings every hour, including:

- Glasgow Coma Score broken down by eyes, voice, motor scores. (See Table 1.)

- Presence of gross focal neurologic signs and/or deficit.

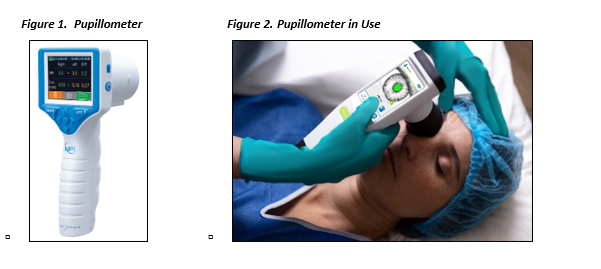

- Pupil size and reactivity. See below Figures 1 and 2.

- When available, quantitative pupillometry should be assessed and documented to ensure accuracy and consistency of recordings.31-33 Quantitative pupillometry and the neurologic pupillary index (NPi) allows objective and consistent assessment of pupillary reactivity to track trends and determine if a patient’s responsiveness is worsening. ICU nurses should be documenting these findings and they should be trended.

- NPi < 3.0 is concerning for an abnormal or sluggish pupil and therefore increased intracranial pressure. NPi should be documented and significant changes indicate the need to assess or empirically treat for increased intracranial pressure. If a neurosurgeon is not managing the patient; telehealth support to review NPi should be considered. (See Appendix D.)

Medical Management

There is a delicate balance when sedating patients with TBI. When transferring casualties to a neurosurgical capability for initial assessment, avoid long-lasting sedation or paralysis as this impedes the ability to evaluate the patient. However, medication selection should not override the need to safely transport the casualty.

- Propofol can be used for sedation, but caution must be used to avoid hypotension.25

- Ketamine is also useful for sedation (and can also provide some analgesia) as it avoids the significant hypotension associated with propofol and there is evidence it lowers intracranial pressure (ICP).34-40

- When narcotics are utilized for pain management, intermittent narcotic doses are preferred over continuous infusion.

- Routine paralysis of TBI patients should be avoided. If paralytics are needed, vecuronium is preferred because it is readily available in the austere environment and does not require refrigeration. Bolus dosing is preferred over continuous infusion. The recommended initial dose is 0.08 to 0.1 mg/kg given as an intravenous bolus injection. Paralytics should only be used if the patient is appropriately sedated. In general, paralytics should only be used for high-risk transport.

Despite controversy on the use of invasive monitoring to measure ICP, treatment of known or suspected intracranial hypertension remains a cornerstone of therapy in patients with severe brain injury.42

Intracranial hypertension should be suspected based on certain clinical criteria if no CT scan or intracranial monitor is available. These criteria include:

- GCS Motor Score < 4

- Pupillary asymmetry

- Interval development of pupillary asymmetry > 2mm

- Abnormal pupil reactivity

- Decrease of motor score by > 1

- New motor deficit

- Hypertension with Bradycardia

- If an automated pupillometer is present, an NPi < 3 on one or both eyes is concerning for raised intracranial pressure.

If treatment for intracranial hypertension is indicated prior to arrival to a neurosurgical capability, initiate hyperosmotic therapy with one of the following:

1. Hypertonic Saline42,43 (Appendix B)

-

- 250ml bolus of 3% saline administered over 10-15 minutes or a 30cc bolus of 23.4% saline.

- In a location with no neurosurgical capability for definitive treatment, infuse 3% saline at 50-100ml/hr for resuscitation with goal serum Na level of 150-160mmol/L. If in the rare circumstance, chronic hyponatremia is suspected, elevation of plasma sodium by 3-5mmol/L over 2-4 hours is recommended.

- Place central venous access to administer hypertonic saline and vasoactive medications, particularly if it is anticipated to be needed long term. Subclavian veins are preferred, followed by femoral, and lastly internal jugular.

2. Mannitol

Avoid Mannitol during the initial resuscitation period when ongoing bleeding has not been ruled out and in hypotensive casualties (or any casualty with the risk of bleeding).

Consider using Mannitol only if there is no availability of hypertonic saline and there is a significant concern for imminent herniation as evidenced by signs of intracranial hypertension described above.

-

- Mannitol 1g/kg bolus IV.25

- Hypotension after mannitol administration must be predicted and avoided. Urine output should be replaced with isotonic fluids.

- When treating patients with osmotic agents, monitor serum sodium at least every 6 hours.

ANTIEPILEPTIC MEDICATIONS AND SEIZURES

Seizures are common after severe brain trauma. Administer seizure prophylaxis to avoid the hemodynamic changes and increased cerebral metabolic activity caused by seizures. Seizure medications help prevent early post-traumatic seizures, but do not prevent all seizures. Up to 25% of patients with severe TBI will have seizures even with prophylactic treatment. Fifty percent of seizures may be non-convulsive in nature. Patients with subdural hematoma, neurosurgical procedure, or penetrating brain injury are at the highest risk of seizures. Post-traumatic seizures have been shown to increase morbidity and mortality after trauma.44-47

- If severe TBI is suspected, seizure prophylaxis should be administered during the initial evaluation and within 30 minutes of arrival.

- Preferred agent: Levetiracetam (Keppra) 1500mg IV loading dose, followed by 1000mg IV BID

- Second line agent: Lacosamide (Vimpat) 400mg IV loading dose, followed by 200mg IV q12hours.

- Continue seizure prophylaxis for 7 days after a moderate or severe TBI.25,48-52 (Appendix A)

- Seizure medications should be continued past post-injury day seven if the patient had evidence of seizure activity.

- Rapid assessment and treatment of seizures is important to prevent secondary neurologic insult. Use a rapid response EEG device (if available) to diagnose seizures accurately and quickly.54-58

- Active Seizures

Lorazepam 1-2mg IV or Midazolam 5-10mg IV. Lorazepam is preferred. If no IV access, Midazolam IM is as effective as Lorazepam IV

- Maintain normothermia. Avoid and treat hyperthermia.

- Elevate head of bed to 30-45° or use reverse Trendelenburg position for suspected concomitant spine/spinal cord injuries.

- Gastric ulcer prevention with an IV PPI should be started within 12 hours of admission.

- Consider enteral nutrition according to Nutritional Support Using Enteral and Parenteral Methods.59

Aeromedical Evacuation Considerations

Coordinating care between sending and receiving physicians is of paramount importance during patient movement. Neurosurgeons should discuss all patients being transferred to Role 4 with the receiving neurosurgical team to ensure a common understanding of the patient and the risks and benefits of aeromedical evacuation. Casualties with severe TBI should be manifest with altitude restrictions and the cabin pressured to 5000ft. PaO2 and SaO2 should be closely monitored in flight given the risk of barometric changes in PaO2.

INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

ICP monitoring is recommended during aeromedical evacuation for patients who would meet the requirements stated below in the surgical management section.61

If appropriate neurosurgical capability and bed capacity are available, observation in theater may be warranted for patients with borderline ICP measurements. Stresses of flight including vibration, temperature, noise, movement, light, hypoxia, and altitude have been shown to increase ICP.62,63

Delayed evacuation may improve outcomes in patients with ongoing resuscitation needs and intracranial hemorrhage or decreased GCS. Since most intubated patients require heavy sedation and often paralysis during transport, neurologic exam cannot be followed and a neurologic deterioration may not be detected for many hours. Some patients have suffered herniation during long range evacuation. For example, this has occurred with patients who have significant burns requiring resuscitation who have intracranial hemorrhage or cerebral edema.

Do not remove a functional ICP monitor in the immediate period prior to aeromedical evacuation. This provides information to the Critical Care Air Transport Team (CCATT) team that can direct in flight treatment. Furthermore, it offers a level of safety in terms of stable ICP in patients who may otherwise require sedation or not have a reliable neurological exam.

Do not remove drains in the immediate period prior to aeromedical evacuation due to the risk of bleeding.

The effect of increasing altitude on contained air within the body, including the cranium, will potentially result in expansion of pneumocephalus; this is particularly true for those who have not undergone a decompressive craniectomy prior to the flight.

All patients should be transported with head of bed elevation or reverse Trendelenberg at 30-45°. Typically U.S. Air Force doctrine is to load all patient’s feet first into the aircraft.62 In a patient with TBI, the aeromedical transport physician may consider loading headfirst, to maintain head elevation during flight.

DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS PROPHYLAXIS

All patients should be started on mechanical Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis at a minimum using sequential compression devices on uninjured extremities.

All trauma patients who are non-ambulatory require DVT prophylaxis, including brain-injured casualties. Chemical DVT prophylaxis in all moderate to severe head injured patients with normal coagulation profile should be started once there is a documented stable head CT, ideally no later than 24 hours after injury.

Caution in starting DVT prophylaxis and discussion with neurosurgeon is recommended for the following conditions:

- Polytrauma with or at risk for coagulopathy.

- Have intracranial monitor/drain in place.

- Have one or more of the following TBI features that are “high risk” for progression according to the Norwood-Berne criteria:

- Subdural hematoma (SDH) > 8mm

- Epidural hemorrhage > 8mm

- Largest single contusion > 2cm

- More than one contusion per lobe

- Diffuse or scattered subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Diffuse or scattered intraventricular hemorrhage.

For these patients, chemical prophylaxis may be started 72 hours post-injury or as neurosurgeon recommends (reference) 64,65

Enoxaparin 30mg subcutaneous BID (preferred) or subcutaneous heparin, 5000U TID may be used as chemoprophylaxis.25,66-68

Multimodality Monitoring Of Head Injuries

Non-operative management of intracranial hemorrhage requires neurosurgical consultation, repeat imaging until CT scan is stable, and serial exams.

Surgical intervention may be indicated in the management of patients with severe brain injury. This includes operative care such as evacuation of space-occupying hematomas via craniectomy or craniotomy as well as placement of multimodal intracranial monitors.

INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE MONITORING

Management of severe TBI patients using information from ICP monitoring is recommended. Although long-term outcomes have not been shown to be improved with ICP monitoring, there is evidence that in-hospital and two-week post-injury mortality is improved.22 Additionally, the military trauma system may require multiple patient movements and handoffs that decrease the ability to follow neurologic exams. Therefore, ICP monitoring may detect a deterioration that would normally be detected on serial neurologic exam in a stable ICU environment.

ICP monitoring should be considered in all salvageable patients with:

- Severe TBI and abnormal CT showing one or more of the following:

- hematoma

- contusion

- edema

- herniation

- compressed basal cisterns.25

- Severe TBI and a normal CT if 2 or more of the following are noted:

- Age >40

- Unilateral or bilateral posturing

- Systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg.25

Additionally, a low threshold for ICP monitoring should be maintained in severe TBI patients with any abnormal head CT and inability to follow serial neurologic exam such as during other surgical interventions required early after injury, long-range evacuation of intubated patients, etc.

Options for ICP monitoring:25

- External ventricular drain (ventriculostomy tube)

- Parenchymal ICP monitors. Codman ICP monitors are the only intraparenchymal device with aeromedical certification approved for U.S. Air Force aircraft.

If using antibiotic impregnated ventriculostomy, then no IV prophylactic antibiotics required. Otherwise, Ancef 1gm IV TID may be prescribed while ventriculostomy is in place (neurosurgeon’s discretion). The goal ICP is <22 mmHg.25

Cerebral perfusion pressure is defined as: CPP = MAP-ICP. 22 The goal cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is between 60-70 mmHg when the autoregulator status of the patient is uncertain.

Brain Tissue Oxygen Monitoring

- Aeromedical evacuation may decrease continuous brain tissue oxygen (PbtO2).33,69,70 There is evidence that the combined management of PbtO2 and ICP may improve outcomes of neurologic function in patients with severe TBI.

- Consider placement of a multi-modality intra-parenchymal catheter for monitoring of both PbtO2 and ICP

- PbtO2 should be maintained greater than 20mmHg.

- Strategies for managing PbtO2 and ICP are outlined in Appendix A under Treatment Paradigms Operative Care by Neurosurgery based on CT results: Evacuation of Hematoma.

Note This monitoring capability may not be readily available, parameters have been outlined here in case these monitoring strategies are applicable in the future.

Indications For Neurosurgical Intervention

Epidural Hematoma

All epidural hematomas > 30cc should be surgically evacuated regardless of the patient’s GCS.25

EDH <30cc and with less than 15mm thickness and less than 5mm midline shift with a GCS >8 without a focal deficit may be managed non-operatively with appropriate monitoring in the ICU setting. These patients should be urgently transported to an MTF with neurosurgical capability for monitoring in case they decompensate.

Craniotomy for evacuation of an acute SDH with a thickness >10mm or midline shift > 5mm regardless of the patient’s GCS.

Craniotomy for evacuation of acute SDH with a thickness <10mm and shift <5 mm is indicated when there is a decrease in GCS of 2 or more, worsening pupillary exam, and/or and ICP greater than 20mm Hg. 25

Craniotomy for evacuation of a hematoma is indicated in a patient with GCS of 6-8 with frontal or temporal contusions greater than 20 cc in volume with midline shift or at least 5mm and/or cisternal compression on CT. 25

Craniotomy for evacuation of a hematoma is also indicated in patients with lesions greater than 50 cc in volume in a salvageable patient.

Mass effect on non-contrast CT or with neurological dysfunction or deterioration due to the lesion should undergo operative intervention as soon as possible. 25

A high index of suspicion is required for penetrating injuries of the skull base or across known major vascular territories. All penetrating brain injuries should undergo a CT Angiogram or Digital Subtraction Angiogram to rule out or diagnose a traumatic aneurysm as soon as possible.8

Removal of devitalized brain tissue is an option in penetrating head injuries and in select cases of open skull fractures.71

The routine pursuit of individual foreign bodies (e.g., bullets, metallic fragments, bone) within the brain may cause additional tissue damage and is generally not advisable but should be left to the discretion of the neurosurgeon. Removal of fragments from the sensory, motor, or language cortex may reduce the risk of posttraumatic epilepsy.72

Primary dural closure or limited duroplasty should be done in extremely limited instances as cerebral edema can progress in both severe and penetrating traumatic brain injury. Commonly, duragen or other dural substitute should be used as an overlay in the vast majority of cases during a decompressive hemicraniectomy. Dura can be reconstructed with temporalis fascia or fascia lata if a dural substitute is not available.71

Surgical decompression, or craniectomy, should be strongly considered following penetrating combat brain trauma.5,73,74

The kinetics of combat trauma can be very different from that seen in the civilian setting. The muzzle velocities of military rifles are much higher than civilian handguns which may lead to cavitation and surrounding devitalized tissue. Additionally, blasts can create four to five different classes of injury to the brain and other organ systems complicating management.75

- Primary blast injury: blast overpressure from pressure waves.

- Secondary blast injury: penetrating fragmentation injuries.

- Tertiary blast injury: displacement of the casualty or blast debris that falls on the casualty.

- Quaternary blast injury: injury from the thermal effect or release of toxins from the blast.

During transport, interventions for intracranial hypertension are limited to medical management. Craniectomy and en route monitoring devices may facilitate earlier CCATT transport of patients out of theater, however long-range evacuation is not a benign intervention and may increase secondary brain injury. In cases of elevated ICP or in the early postoperative period, patients may be better served by delayed evacuation if possible.

Options for U.S. and Coalition Patients:

- Those who have penetrating brain trauma: Do not save or send the calvarium as alloplastic reconstruction techniques are used for these casualties.

- Those who have blunt trauma: Consider abdominal subcutaneous implantation of the calvarial flap for later reconstruction if it can be done in a sterile fashion.

Options for Host Nation Patients:

- Clean and replace.

- Clean and replace with hinge craniectomy. This involves partial fixation of the superior aspect of the bone flap, allowing it to “hinge” outward to accommodate swelling.76

- Craniectomy with potentially limited chances for cranioplasty in the future, depending on local rules of eligibility.

- In some locations, low temperature tissue freezing may be possible to allow replacement at a later time.

Exploratory Burr Holes (if no neurosurgeon or CT scan is available)

Exploratory burr holes have limited practical utility. They should only be performed by a neurosurgeon or after consultation with a neurosurgeon if possible and at a location where CT scan is not available to better guide management. Refer to the CPG entitled Emergency Life-Saving Cranial Procedures by Non-Neurosurgeons in Deployed Setting for additional guidance.

ICP Monitoring and Surgical Intervention (for Host Nation Patients)

Decisions to place ICP monitors or operate on host nation nationals should consider the available resources in the host nation for long-term care and rehabilitation.

Performance Improvement Monitoring

- All patients with a diagnosis of traumatic brain injury and an initial GCS of 3-8.

- All patients who receive a cranial procedure (ICP monitor, craniectomy, craniotomy).

- All patients in population of interest avoid hypotension and hypoxia: SBP never < 110 mmHg, MAP never < 60mmHg, SaO2 never < 93%.

- All patients in population of interest have PaCO2 monitored at every role of care; PaCO2 should not be >45mmHg or <35mmHg.

- All patients in population of interest have a head CT performed within 4 hours of injury and surgical intervention (if necessary) within 5 hours of injury.

- All patients with a ventriculostomy have hourly documentation of ICP/CPP and ventriculostomy output.

- All patients in population of interest who are unable to be monitored clinically (e.g., unable to hold sedation for Q1 hour neuro exam) have an ICP monitor or ventriculostomy placed prior to transport out of theater.

- Number and percentage of patients in the population of interest with lowest SBP<110 within first 3 days after injury.

- Number and percentage of patients in the population of interest with MAP<60 within first 3 days after injury.

- Number and percentage of patients in the population of interest with SaO2<93% within first 3 days after injury.

- Number and percentage of patients in population of interest who have PaCO2 documented at every role of care (POI, POI MEDEVAC, Role 2-4, interfacility MEDEVAC).

- Number and percentage of patients in the population of interest who maintain PaCO2=35-45mmHg.

- Number and percentage of patients who had a head CT performed within 4 hours of injury.

- Number and percentage of patients who had a craniectomy performed within 5 hours of injury.

- Number and percentage of patients with a ventriculostomy who had hourly documentation of ICP/CPP and ventriculostomy output.

- Number and percentage of patients in the population of interest unable to be monitored clinically (e.g., unable to hold sedation for Q1 hour neuro exam) who have an ICP monitor or ventriculostomy placed prior to transport out of theater.

- Patient Record

- DoDTR

- ICU flow sheet

- Neurologic assessment flow sheet

SYSTEM REPORTING & FREQUENCY

The above constitutes the minimum criteria for PI monitoring of this CPG. System reporting will be performed annually; additional PI monitoring and system reporting may be performed as needed.

The system review and data analysis will be performed by the JTS Chief and the JTS PI team.

It is the trauma team leader’s responsibility to ensure familiarity, appropriate compliance, and PI monitoring at the local level with this CPG.

References

- (NVSS) NVSS. In: CDC National Center for Health Statistics. 2006-2010.

- Breeze J, Bowley DM, Harrisson SE, et al. Survival after traumatic brain injury improves with deployment of neurosurgeons: a comparison of US and UK military treatment facilities during the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020, 91(4):359-365.

- Bell RS, Vo AH, Neal CJ, et al. Military traumatic brain and spinal column injury: a 5-year study of the impact blast and other military grade weaponry on the central nervous system. J Trauma 2009, 66(4 Suppl):S104-111.

- Bell RS, Mossop CM, Dirks MS, et al. Early decompressive craniectomy for severe penetrating and closed head injury during wartime. Neurosurg Focus 2010, 28(5):E1.

- DuBose JJ, Barmparas G, Inaba K, et al. severe traumatic brain injuries sustained during combat operations: demographics, mortality outcomes, and lessons to be learned from contrasts to civilian counterparts. J Trauma 2011, 70(1):11-16; discussion 16-18.

- Weisbrod AB, Rodriguez C, Bell R, et al. Long-term outcomes of combat casualties sustaining penetrating traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012, 73(6):1525-1530.

- Nakase-Richardson R, McNamee S, et al. Descriptive characteristics and rehabilitation outcomes in active-duty military personnel and veterans with disorders of consciousness with combat- and noncombat-related brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013, 94(10):1861-1869.

- Bell RS, Vo AH, Roberts R, et al. Wartime traumatic aneurysms: acute presentation, diagnosis, and multimodal treatment of 64 craniocervical arterial injuries. Neurosurgery 2010, 66(1):66-79.

- Shackelford SA, Del Junco DJ, Reade MC, et al. Association of time to craniectomy with survival in patients with severe combat-related brain injury. Neurosurg Focus. 2018 Dec 1;45(6):E2.

- Turner CA, Stockinger ZT, Gurney JM. Combat surgical workload in Operation Iraqi Freedom & Enduring Freedom: the definitive analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 Jul;83(1):77-83.

- Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, et al. Death on the battlefield (2001-2011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Dec;73(6 Suppl 5):S431-7.

- Eastridge BJ, Hardin M, Cantrell J, et al. Died of wounds on the battlefield: causation and implications for improving combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2011 Jul;71(1 Suppl):S4-8.

- DuBose JJ, Barmparas G, Inaba K, et al. Isolated severe traumatic brain injuries sustained during combat operations: demographics, mortality outcomes, and lessons to be learned from contrasts to civilian counterparts. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2011 Jan;70(1):11-6; discussion 16-8.

- Tadlock MD, Gurney J, Tripp MS, et al. Between the devil and the deep blue sea: A review of 25 modern naval mass casualty incidents with implications for future distributed maritime operations. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021 Aug 1;91(2S Suppl 2):S46-S55.

- Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, et al. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (SCAT5). British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017:bjsports-2017-2010.

- Khokhar B, Jorgensen-Wagers K, Marion D, Kiser S. Military acute concussion evaluation: a report on clinical usability, utility, and user's perceived confidence. J Neurotrauma 2020.

- Coldren RL, Kelly MP, Parish RV, et al. Evaluation of the military acute concussion evaluation for use in combat operations more than 12 hours after injury. Mil Med 2010, 175(7):477-481.

- Chapleau W A-kJ, Haskin D, et al. Advanced Trauma Life Support Manual, 9th Edition. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2012.

- Cooper DJ, Myburgh J, Heritier S, et al. Albumin resuscitation for traumatic brain injury: is intracranial hypertension the cause of increased mortality? J Neurotrauma 2013, 30(7):512-518.

- East JM, Viau-Lapointe J, McCredie VA. Transfusion practices in traumatic brain injury. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 2018, 31(2):219-226.

- CRASH-3 trial collaborators. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394(10210):1713-1723.

- Carney N, Totten AM, O'Reilly C, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery 2017, 80(1):6-15.

- Schreiber MA, Aoki N, Scott BG, Beck JR. Determinants of mortality in patients with severe blunt head injury. Arch Surg 2002, 137(3):285-290.

- Gaitanidis A, Breen KA, Maurer LR, et al. Systolic blood pressure <110 mm hg as a threshold of hypotension in patients with isolated traumatic brain injuries. J Neurotrauma 2020.

- Bratton SL, Chestnut RM, Ghajar J, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2007, 24 Suppl 1:S1-S106.

- Infection prevention in combat-related injuries clinical practice guideline, 27 Jan 2021.

- Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2009, 360(13):1283-1297.

- Edwards P, Arango M, Balica L, et al. Final results of MRC CRASH, a randomised placebo-controlled trial of intravenous corticosteroid in adults with head injury-outcomes at 6 months. Lancet 2005, 365(9475):1957-1959.

- Johannigman J, Gerlach T, Cox D, et al. Hypoxemia during aeromedical evacuation of the walking wounded. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015, 79(4 Suppl 2):S216-220.

- Scultetus AH, Haque A, Chun SJ, et al. Brain hypoxia is exacerbated in hypobaria during aeromedical evacuation in swine with traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016, 81(1):101-107.

- Jahns FP, Miroz JP, Messerer M, et al. Quantitative pupillometry for the monitoring of intracranial hypertension in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care 2019, 23(1):155.

- Couret D, Boumaza D, Grisotto C, et al. Reliability of standard pupillometry practice in neurocritical care: an observational, double-blinded study. Crit Care 2016, 20:99.

- Ong C, Hutch M, Barra M, et al. Effects of osmotic therapy on pupil reactivity: quantification using pupillometry in critically ill neurologic patients. Neurocrit Care 2019, 30(2):307-315.

- Bar-Joseph G, Guilburd Y, Tamir A, Guilburd JN. Effectiveness of ketamine in decreasing intracranial pressure in children with intracranial hypertension. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2009, 4(1):40-46.

- Bourgoin A, Albanese J, Wereszczynski N, et al. Safety of sedation with ketamine in severe head injury patients: comparison with sufentanil. Crit Care Med 2003, 31(3):711-717.

- Chang LC, Raty SR, Ortiz J, Bailard NS, Mathew SJ. The emerging use of ketamine for anesthesia and sedation in traumatic brain injuries. CNS Neurosci Ther 2013, 19(6):390-395.

- Cornelius BG, Webb E, Cornelius A, et al. Effect of sedative agent selection on morbidity, mortality, and length of stay in patients with increase in intracranial pressure. World J Emerg Med 2018, 9(4):256-261.

- Gregers MCT, Mikkelsen S, Lindvig KP, Brochner AC. Ketamine as an anesthetic for patients with acute brain injury: a systematic review. Neurocrit Care 2020, 33(1):273-282.

- Oddo M, Crippa IA, Mehta S, et al. Optimizing sedation in patients with acute brain injury. Crit Care 2016, 20(1):128.

- Zeiler FA, Teitelbaum J, West M, Gillman LM. The ketamine effect on ICP in traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care 2014, 21(1):163-173.

- Chesnut RM, Temkin N, Carney N, et al. A trial of intracranial-pressure monitoring in traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 2012, 367(26):2471-2481.

- Lazaridis C, Neyens R, Bodle J, DeSantis SM. High-osmolarity saline in neurocritical care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2013, 41(5):1353-1360.

- Qureshi AI, Suarez JI. Use of hypertonic saline solutions in treatment of cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension. Crit Care Med 2000, 28(9):3301-3313.

- Vespa PM, Nuwer MR, Nenov V, et al. Increased incidence and impact of nonconvulsive and convulsive seizures after traumatic brain injury as detected by continuous electroencephalographic monitoring. J Neurosurg 1999, 91(5):750-760.

- Fordington S, Manford M. A review of seizures and epilepsy following traumatic brain injury. J Neurol 2020, 267(10):3105-3111.

- Majidi S, Makke Y, Ewida A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for early seizure in patients with traumatic brain injury: analysis from National Trauma Data Bank. Neurocrit Care 2017, 27(1):90-95.

- Ronne-Engstrom E, Winkler T. Continuous EEG monitoring in patients with traumatic brain injury reveals a high incidence of epileptiform activity. Acta Neurol Scand 2006, 114(1):47-53.

- Szaflarski JP, Sangha KS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Prospective, randomized, single-blinded comparative trial of intravenous levetiracetam versus phenytoin for seizure prophylaxis. Neurocrit Care 2010, 12(2):165-172.

- Kwon SJ, Barletta JF, Hall ST, et al. Lacosamide versus phenytoin for the prevention of early post traumatic seizures. J Crit Care 2019, 50:50-53.

- Davidson KE, Newell J, Alsherbini K, Krushinski J, Jones GM. Safety and efficiency of intravenous push lacosamide administration. Neurocrit Care 2018, 29(3):491-495.

- Hall EA, Wheless JW, Phelps SJ: Status epilepticus: the slow and agonizing death of phenytoin. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2020, 25(1):4-6.

- Strzelczyk A, Zollner JP, Willems LM, et al. Lacosamide in status epilepticus: Systematic review of current evidence. Epilepsia 2017, 58(6):933-950.

- Gururangan K, Razavi B, Parvizi J. Diagnostic utility of eight-channel EEG for detecting generalized or hemispheric seizures and rhythmic periodic patterns. Clin Neurophysiol Pract 2018, 3:65-73.

- Hobbs K, Krishnamohan P, Legault C, et al. Rapid bedside evaluation of seizures in the ICU by listening to the sound of brainwaves: a prospective observational clinical trial of Ceribell's Brain Stethoscope Function. Neurocrit Care 2018, 29(2):302-312.

- Kamousi B, Grant AM, Bachelder B, et al. Comparing the quality of signals recorded with a rapid response EEG and conventional clinical EEG systems. Clin Neurophysiol Pract 2019, 4:69-75.

- Parvizi J, Gururangan K, Razavi B, Chafe C. Detecting silent seizures by their sound. Epilepsia 2018, 59(4):877-884.

- Vespa PM, Olson DM, John S, et al. Evaluating the clinical impact of rapid response electroencephalography: the DECIDE Multicenter Prospective Observational Clinical Study. Crit Care Med 2020, 48(9):1249-1257.

- Yazbeck M, Sra P, Parvizi J. Rapid response electroencephalography for urgent evaluation of patients in community hospital intensive care practice. J Neurosci Nurs 2019, 51(6):308-312.

- .Joint Trauma System. Support using enteral and parenteral methods CPG. Mil Med 2018, 183(suppl_2):153-160.

- Goodman MD, Makley AT, Lentsch AB, et al. brain injury and aeromedical evacuation: when is the brain fit to fly? J Surg Res 2010, 164(2):286-293.

- Pastorek R, Cripps M, Bernstein I, et al. The Parkland Protocol’s Modified Berne-Norwood Criteria predict two-tiers of risk for traumatic brain injury progression. J of Neurotrauma 2014; 31: 1737-1743.

- Johannigman JA, Zonies D, Dubose J, et al. Reducing secondary insults in traumatic brain injury. Mil Med 2015, 180(3 Suppl):50-55.

- Hawryluk GWJ, Aguilera S, Buki A, et al. A management algorithm for patients with intracranial pressure monitoring: the Seattle International Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Consensus Conference (SIBICC). Intensive Care Med 2019, 45(12):1783-1794.

- Phelan HA, Eastman AL, Madden CJ, et al. TBI risk stratification at presentation: A prospective study of the incidence and timing of radiographic worsening in the Parkland Protocol. J Trauma Acute Care 2012; 73: S122-S127.

- Latronico N, Berardino M. Thromboembolic prophylaxis in head trauma and multiple-trauma patients. Minerva Anestesiol 2008, 74(10):543-548.

- Meyer RM, Larkin MB, Szuflita NS, et al. Early venous thromboembolism chemoprophylaxis in combat-related penetrating brain injury. J Neurosurg 2017, 126(4):1047-1055.

- Dengler BA, Mendez-Gomez P, Chavez A, et al. Safety of chemical DVT prophylaxis in severe traumatic brain injury with invasive monitoring devices. Neurocrit Care 2016, 25(2):215-223.

- Okonkwo DO, Shutter LA, Moore C, et al. Brain oxygen optimization in severe traumatic brain injury phase-ii: a phase ii randomized trial. Crit Care Med 2017, 45(11):1907-1914.

- Skovira JW, Kabadi SV, Wu J, et al. Simulated aeromedical evacuation exacerbates experimental brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2016, 33(14):1292-1302.

- Giannou C BM, Molden A. Cranio-cerebral Injuries, vol. 2. Geneva, Switzerland; 2013.

- Salazar AM, Jabbari B, Vance SC, Grafman J, Amin D, Dillon JD. Epilepsy after penetrating head injury. Clinical correlates: a report of the Vietnam Head Injury Study. Neurology 1985, 35(10):1406-1414.

- Ecker RD, Mulligan LP, Dirks M, et al. Outcomes of 33 patients from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan undergoing bilateral or bicompartmental craniectomy. J Neurosurg 2011, 115(1):124-129.

- Ragel BT, Klimo P, Jr., Martin JE, et al. Wartime decompressive craniectomy: technique and lessons learned. Neurosurg Focus 2010, 28(5):E2.

- Wolf SJ, Bebarta VS, Bonnett CJ, Pons PT, Cantrill SV. Blast injuries. Lancet 2009, 374(9687):405-415.

- Schmidt JH, 3rd, Reyes BJ, Fischer R, Flaherty SK. Use of hinge craniotomy for cerebral decompression. Technical note. J Neurosurg 2007, 107(3):678-682.

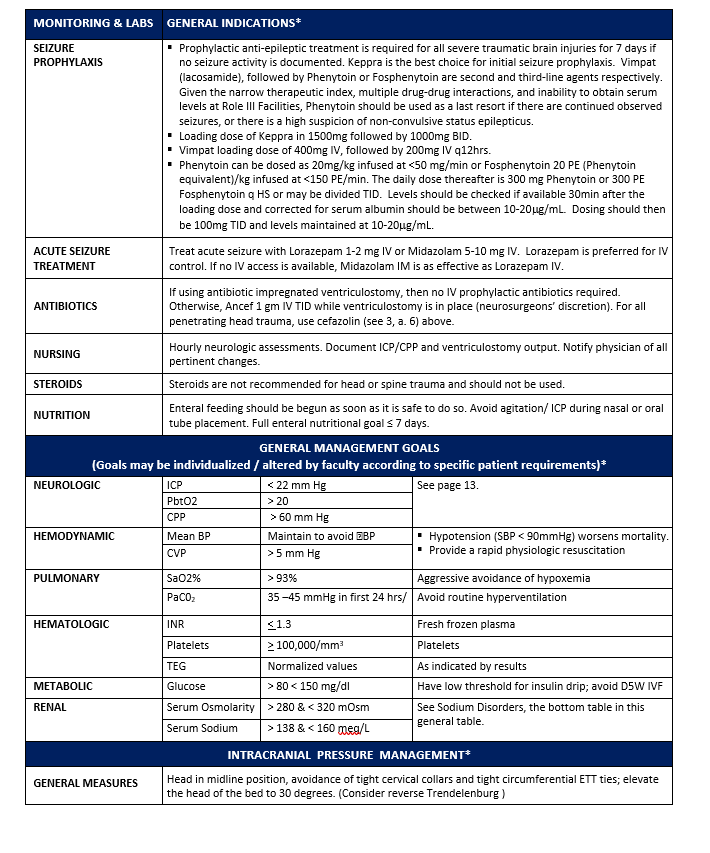

Appendix A: General Indications

Appendix B: Hypertonic Saline Protocol

Hypertonic (3% saline) may be delivered via peripheral IV or intraosseous access.

1. Give 250cc 3% sodium chloride (NaCl) bolus IV (children 5 cc/kg) over 10–15 minutes.

2. Follow bolus with infusion of 3% NaCl at 50 cc/hour.

3. If awaiting transport; check serum Na+ levels every hour:

- If Na < 150 mEq/L re-bolus 150 cc over 1 hour then resume previous rate

- If Na 150–154, increase NaCl infusion 10 cc/hour.

- If Na 155–160, continue infusion at current rate.

- If Na >160, hold infusion, recheck in 1 hour.

4. Once Na is within the range- continue to follow the serum Na+ level every 6 hours

5. After cessation of 3% NaCl infusion, and there is no further concern for cerebral edema the Na Levels should be lowered gradually back to the normal range. Recommend decreasing Na by 5mEq/L each day until normal and continuing to monitor at regular intervals for 24hrs after cessation of hypertonic saline.

6. A 30cc Bolus of 23.4% NaCl can also be given over 10-15 minutes. Can be given as IV piggyback or as an IV push over 10-15 minutes by an experienced provider.

Appendix C: Clinical Use Of Pupillometry

Purpose

To provide guidelines for the use of automated pupillometer in critical care patients with intracranial injuries. This guideline incorporates recent literature defining threshold parameters of normal versus abnormal in order to clarify when nursing staff should contact the primary team for re-evaluation. These guidelines are not a substitute for clinical judgment, but rather an approved multidisciplinary approach to optimize this clinical tool to identify neurologic worsening early while avoiding unnecessary alarms for the primary team.

This guideline applies to all patients for whom there is an intracranial neurologic injury with risk of decompensation per primary team.

Background

The pupillary light reflex (PLR) has long been a clinical sign used to prognosticate and monitor brain injured patients. This neuronal circuit transverses the mid-brain and localizes to optic nerve, and oculomotor nerve and also receives blood supply from both anterior and posterior circulation1. Thus, there is interest in using this circuit to both monitor for early brainstem compression from mass lesions,2 and also to identify alterations in circulation from processes such as delayed cerebral ischemia post subarachnoid hemorrhage3 or increased intracranial pressure4,5. A basic neurologic examination includes evaluating the PLR and reporting size and reactivity, however these measurements are very subjective and suffer from poor inter-rater reliability6,7. With the advent of automated pupillometry, objective measures of the PLR can be reliably obtained with very high inter-rater and inter-device reliability8 in civilian9 and military10 populations.

Beyond pupil size and reactivity, multiple metrics (pupil minimum / maximum size, percentage change of pupil, latency, constriction velocity, maximum constriction velocity, dilatation velocity) can be gathered and compared to normative standards. A commonly employed device is the NPi-200 Pupillometer, manufactured by NeuroOptics (Laguna Hills, CA). This device, in addition to gathering the above data, compares the gathered data to established normal values to create a Neurologic Pupillary Index (NPi) score which ranges from 0-5. NPi values < 3.0 reflect an abnormal PLR5. The presence of a decreased constriction velocity (CV < 0.8 mm/s) is also strongly correlated (but independent) to an abnormal NPi as well as independently associated with elevated intracranial pressure11. Developing an understanding of NPi and CV may provide early insight to neurologic deterioration12.

Because of the rather large anatomic localization of the PLR and the ability to monitor the reactivity of this network reliably and accurately, it has been hypothesized that PLR can be used clinically to follow patients at risk for neurologic decline as a component to a regular neurologic examination. NPi values have been correlated with intracranial pressure as well as mass lesions with brainstem / cranial nerve compression2,11. However, more importantly, there is now evidence that changes in the NPi preempts clinical decline.

- In a case series of patients with transtentorial herniation, PLR changes preceded neurologic deterioration by more than 7 hours in half of the subjects13.

- In a cohort of 56 patients who were admitted to Neurologic Intensive Care Unit with subarachnoid hemorrhage, 7 of 12 patients who developed delayed cerebral ischemia had NPi changes with 71.4% of these changes occurring 8 hours prior to clinical deterioration3.

- In a cohort of 134 patients who had intracranial pressure monitoring and were evaluated with serial pupillometry, those subjects with abnormal NPi (< 3.0) had significantly higher peak ICPs (19.6 vs 30.5 mmHg). On average, the transition to an abnormal NPi occurred 15.9 hours prior to peak ICP5.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For all patients at risk for neurologic decline from progression of intracranial lesion (traumatic brain injury, intracranial hemorrhage, intracranial mass lesions, vasospasm, hydrocephalus, etc.) pupillometry should be included and recorded with scheduled nursing neurologic examination.

- If patient’s pupillometry values meet any one of the below criteria, the neurosurgeon should be called to evaluate:

- NPi drops from > 3 to < 3.

- NPi decreases from previous exam > 1.0.

- A new difference in NPi (left eye vs right eye) is >1.0.

- If above thresholds met, then evaluation should include:

- Review of vitals, inputs/outputs, current medications/drips

- Repeat full neurologic examination (GCS, cranial nerves, language, visual fields, motor exam).

- Contact Neurosurgeon on call.

- If deemed appropriate by the Surgical Trauma Intensive Care Unit and Neurosurgery repeat CT head (discussion with Neurosurgery if CTA of head and/or neck also indicated).

- Review and readdresses goals of neuroprotective measures (intracranial pressure, cerebral perfusion pressure, temperature, serum sodium, etc.).

REFERENCES

- Cahill M, Bannigan J, Eustace P. Anatomy of the extraneural blood supply to the intracranial oculomotor nerve. Br J Ophthalmol, 1996. 80(2): p. 177-81.

- Chen JW, Vakil-Gilani K, Williamson KL, Cecil S. Infrared pupillometry, the neurological pupil index and unilateral pupillary dilation after traumatic brain injury: implications for treatment paradigms. Springerplus, 2014. 3: p. 548.

- Aoun SG, Stutzman SE, Vo PN, El Ahmadieh TY, et al. Detection of delayed cerebral ischemia using objective pupillometry in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg, 2019: p. 1-6.

- McNett M, Moran C, Grimm D, Gianakis A. Pupillometry trends in the setting of increased intracranial pressure. J Neurosci Nurs, 2018. 50(6): p. 357-361.

- Chen JW, Gombart ZJ, Rogers S, Gardiner SK, Cecil S, Bullock RM. Pupillary reactivity as an early indicator of increased intracranial pressure: the introduction of the neurological pupil index. Surg Neurol Int, 2011. 2: p. 82.

- Kerr RG, Bacon AM, Baker LL, Gehrke JS, Hahn KD, Lillegraven CL, Renner CH, Spilman SK. Underestimation of pupil size by critical care and neurosurgical nurses. Am J Crit Care, 2016. 25(3): p. 213-9.

- Olson DM, Stutzman S, Saju C, Wilson M, Zhao W, Aiyagari V. Interrater reliability of pupillary assessments. Neurocritical care, 2016. 24(2): p. 251-257.

- Zhao W, Stutzman S, DaiWai O, Saju C, Wilson M, Aiyagari V. Inter-device reliability of the NPi-100 pupillometer. J Clin Neurosci, 2016. 33: p. 79-82.

- Lee MH, Mitra B, Pui JK, Fitzgerald M. The use and uptake of pupillometers in the intensive care unit. Aust Crit Care, 2018. 31(4): p. 199-203.

- Mease, L., R. Sikka, R. Rhees. Pupillometer use: validation for use in military and occupational medical surveillance and response to organophosphate and chemical warfare agent exposure. Mil Med, 2018.

- McNett M, Moran C, Janki C, Gianakis A. Correlations between hourly pupillometer readings and intracranial pressure values. J Neurosci Nurs, 2017. 49(4): p. 229-234.

- Shoyombo I, Aiyagari V, Stutzman S, Atem F. Understanding the relationship between the neurologic pupil index and constriction velocity values. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 6992.

- Papangelou A, Zink EK, Chang WW, et al. Automated pupillometry and detection of clinical transtentorial brain herniation: a case series. Mil Med, 2018. 183(1-2): p. e113-e121.

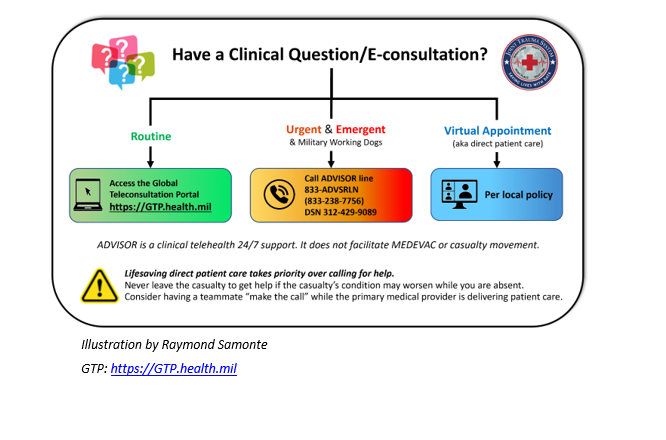

Appendix D: Telemedicine/Teleconsultation

Appendix E: Information Regarding Off-Label Uses in CPGS

The purpose of this Appendix is to ensure an understanding of DoD policy and practice regarding inclusion in CPGs of “off-label” uses of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved products. This applies to off-label uses with patients who are armed forces members.

Unapproved (i.e. “off-label”) uses of FDA-approved products are extremely common in American medicine and are usually not subject to any special regulations. However, under Federal law, in some circumstances, unapproved uses of approved drugs are subject to FDA regulations governing “investigational new drugs.” These circumstances include such uses as part of clinical trials, and in the military context, command required, unapproved uses. Some command requested unapproved uses may also be subject to special regulations.

Additional Information Regarding Off-Label Uses in CPGs

The inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is not a clinical trial, nor is it a command request or requirement. Further, it does not imply that the Military Health System requires that use by DoD health care practitioners or considers it to be the “standard of care.” Rather, the inclusion in CPGs of off-label uses is to inform the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner by providing information regarding potential risks and benefits of treatment alternatives. The decision is for the clinical judgment of the responsible health care practitioner within the practitioner-patient relationship.

Consistent with this purpose, CPG discussions of off-label uses specifically state that they are uses not approved by the FDA. Further, such discussions are balanced in the presentation of appropriate clinical study data, including any such data that suggest caution in the use of the product and specifically including any FDA-issued warnings.

With respect to such off-label uses, DoD procedure is to maintain a regular system of quality assurance monitoring of outcomes and known potential adverse events. For this reason, the importance of accurate clinical records is underscored.

Good clinical practice includes the provision of appropriate information to patients. Each CPG discussing an unusual off-label use will address the issue of information to patients. When practicable, consideration will be given to including in an appendix an appropriate information sheet for distribution to patients, whether before or after use of the product. Information to patients should address in plain language: a) that the use is not approved by the FDA; b) the reasons why a DoD health care practitioner would decide to use the product for this purpose; and c) the potential risks associated with such use.

Download CPG in PDF

READ FULL PDF