Module 7: Airway Management in TFC

Joint Trauma System

Airway Management in TFC

During this module, we will discuss airway management in the Tactical Field Care setting, which involves the process of assessing for potential airway compromise and making decisions regarding which airway maneuvers or interventions will provide the best outcome for a combat casualty. In addition to the didactic presentation and discussion of airway management principles, there are several skills stations where you will have an opportunity to get hands-on practice on the procedures you need to master.

Airway assessments and some interventions are taught to nonmedical personnel with All Service Member or Combat Lifesaver training, and it is important to understand what their training and anticipated skill set is in order to assume care for the casualty and potentially initiate more advanced treatments.

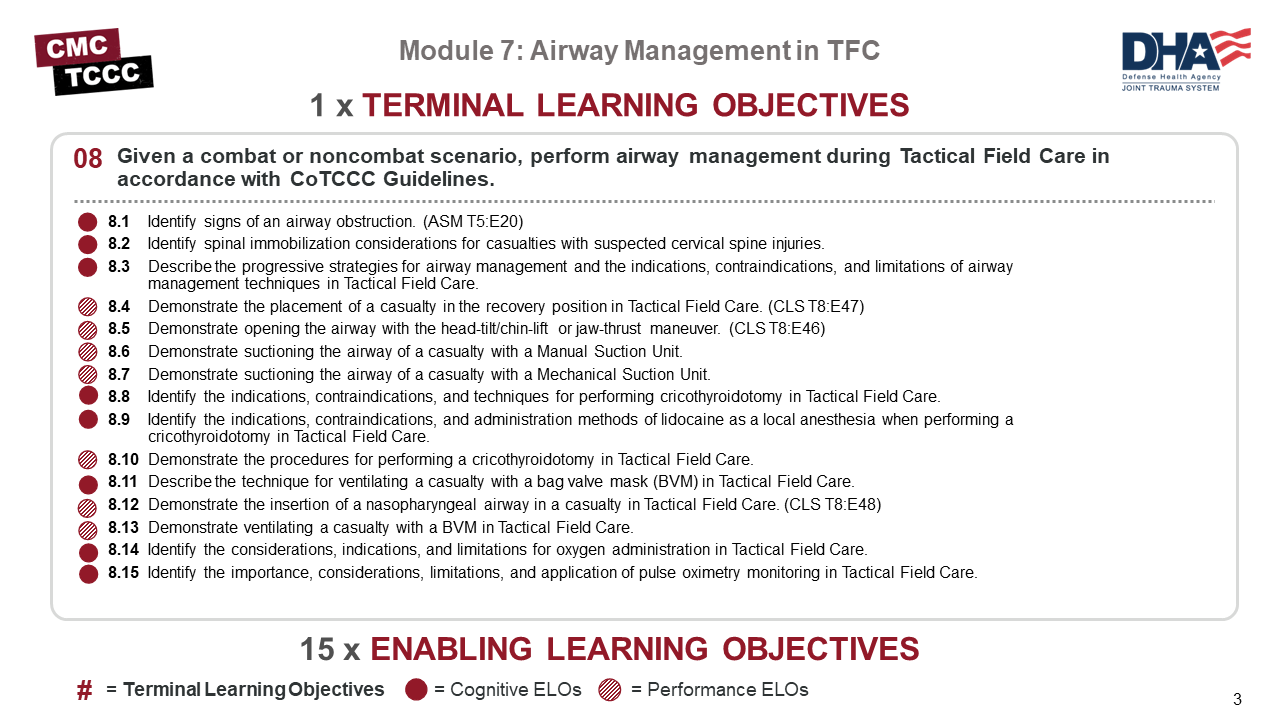

There are 8 cognitive and 7 performance learning objectives for the airway management module; more than any other module in this course.

The cognitive learning objectives include identifying signs of an airway obstruction, understanding considerations for spinal immobilization, describing the progressive strategies for airway management techniques, identifying the indications for establishing an advanced airway and whether to use lidocaine during the procedure, describing ventilation techniques using a bag valve mask, considerations for using oxygen and the importance of pulse oximetry.

The performance learning objectives are opening the airway using a head-tilt/chin-lift or jaw-thrust method, manual and mechanical suctioning, establishing an airway by cricothyroidotomy, placing the casualty in the recovery position and ventilating using a bag valve mask and a nasopharyngeal airway (NPA).

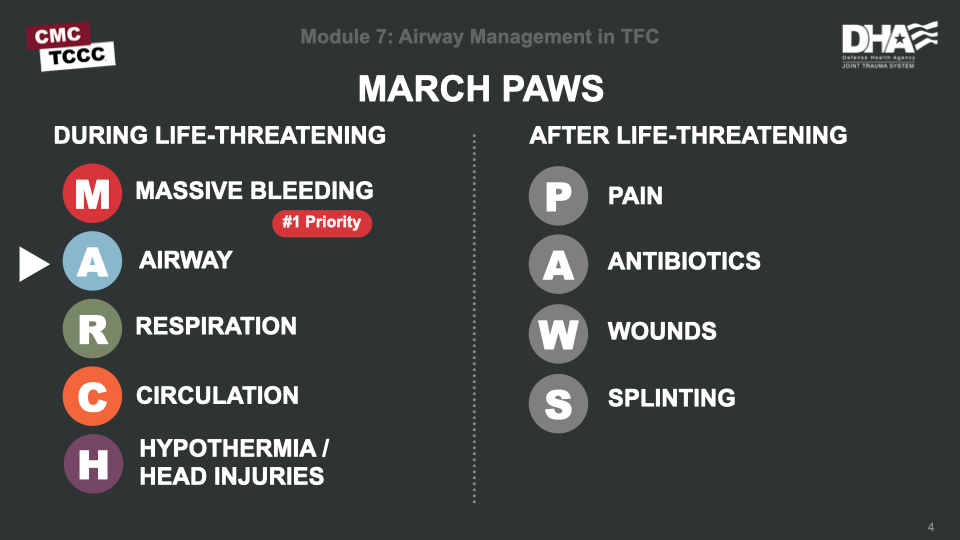

Airway management is the “A” in the MARCH PAWS sequence. In a review of preventable deaths in Afghanistan and Iraq, it was determined 1.8% of the fatalities with potentially survivable injuries died from airway obstruction.

Airway compromise must be addressed at the beginning of the tactical trauma assessment, and the only thing that should delay you is the treatment of massive hemorrhage. If a casualty is conscious and can speak normally, the airway is not obstructed; otherwise, you will need to assess their status.

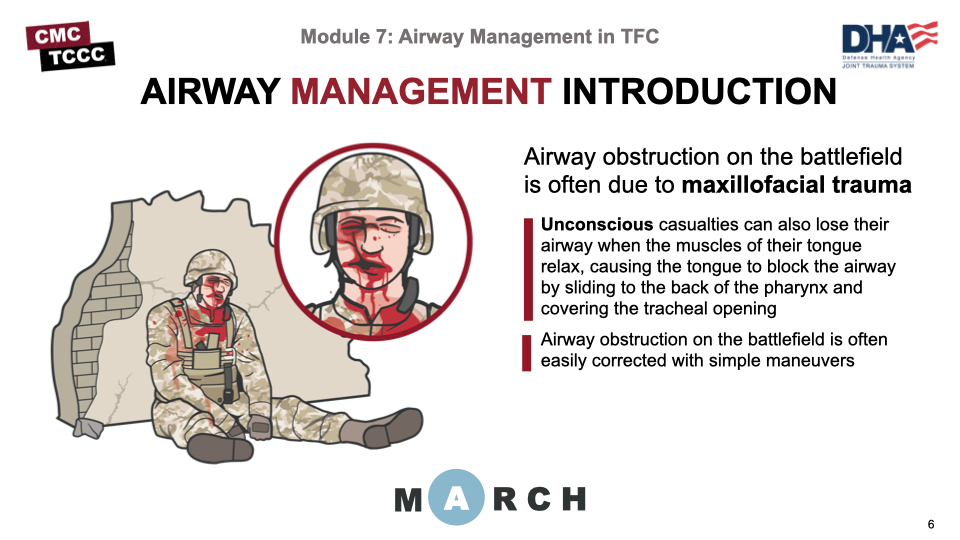

Airway obstruction on the battlefield is most often due to maxillofacial trauma, which may result in disrupted airway anatomy and the intrusion of blood, teeth, or other tissues into the airway.

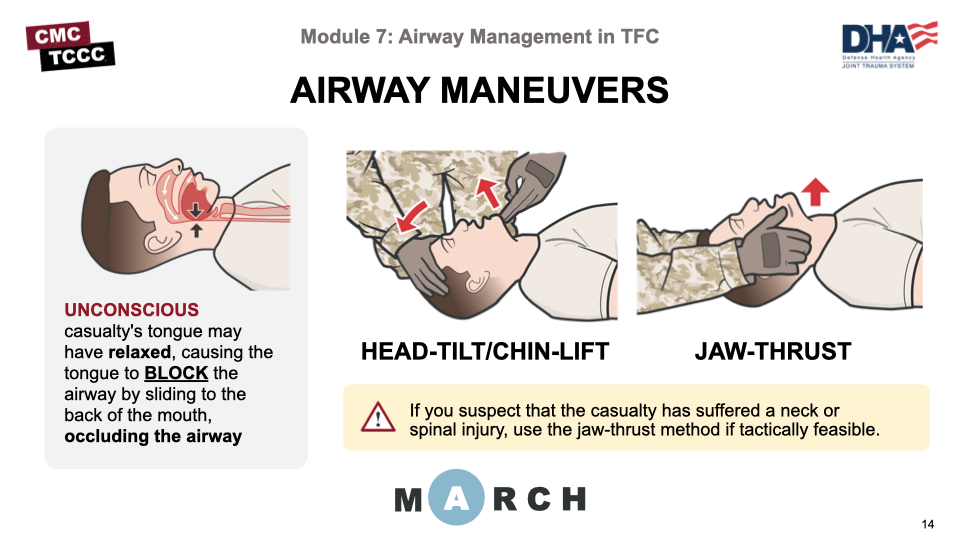

Unconscious casualties can also lose their airway when the muscles of their tongue relax, causing the tongue to block the airway by sliding to the back of the pharynx and covering the tracheal opening.

Airway obstruction on the battlefield is often easily corrected with simple maneuvers.

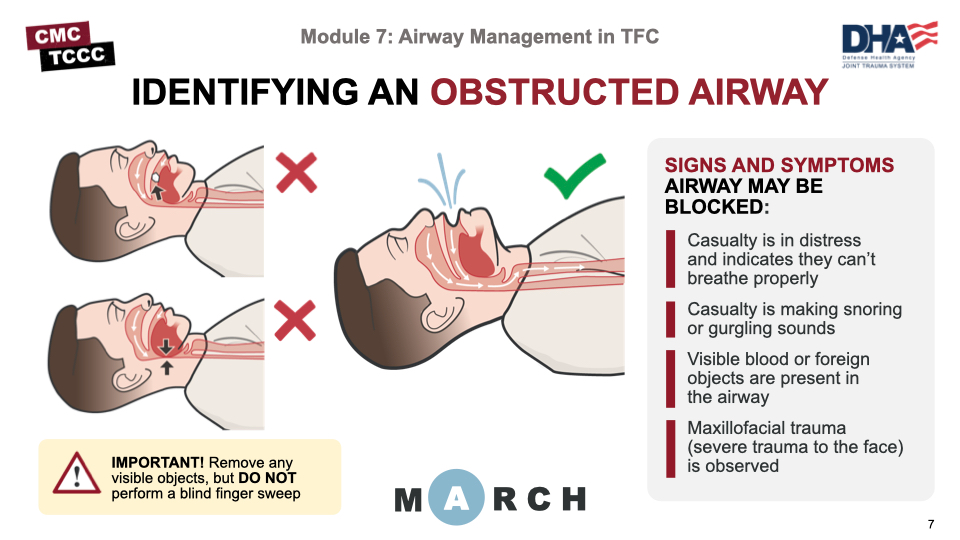

In cases of partial or complete airway obstruction, the casualty may experience agitation, cyanosis, confusion, or even unconsciousness, dyspnea, or high-pitched breathing noises such as stridor, wheezing, snoring, or gurgling sounds.

If you see something in the casualty's mouth (such as foreign material, loose teeth, dentures, facial bone, or vomitus) that could block their airway, use your fingers to remove the material as quickly as possible.

DO NOT perform a blind finger sweep if no foreign body is seen in the casualty’s mouth.

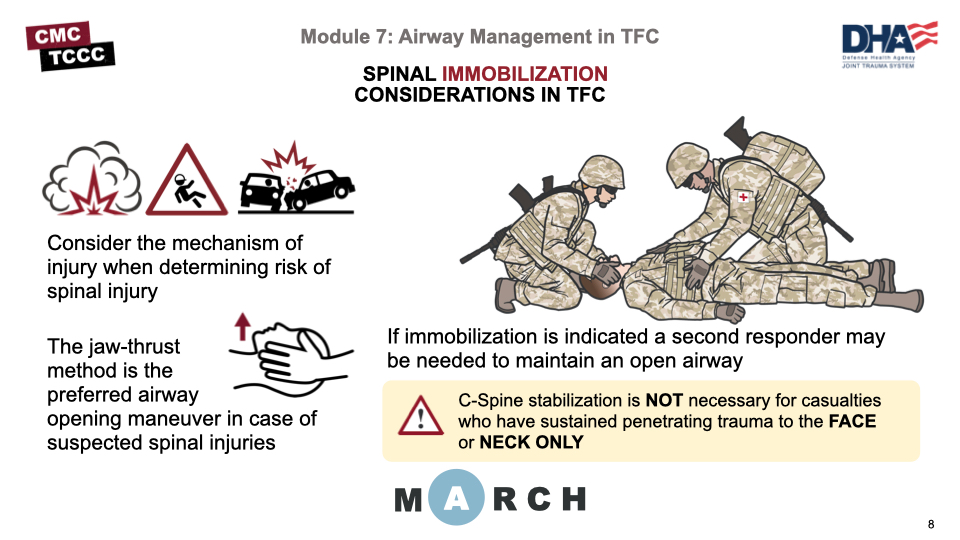

The Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) Guidelines highlight that cervical spine stabilization is not necessary for casualties who have sustained only penetrating trauma.

The Joint Trauma System (JTS) clinical practice guideline on spinal injuries points out that approximately 5.5% of evacuated battle casualties experience a spinal injury, which can occur through a variety of battle-related and nonbattle-related mechanisms. Explosions, motor vehicle accidents, and falls comprise the majority of the mechanisms of injury.

Those same guidelines advise that on the battlefield, preservation of the life of the casualty and medic are of paramount importance, and in those circumstances, evacuation to a more secure area takes precedence over spine immobilization.

That said, if you suspect that the casualty has suffered a neck or spinal injury, use the jaw-thrust method to open an airway, if needed. If a casualty cannot maintain an open airway once opened, a second responder may be needed to assist in maintaining an open airway when using the jaw-thrust method.

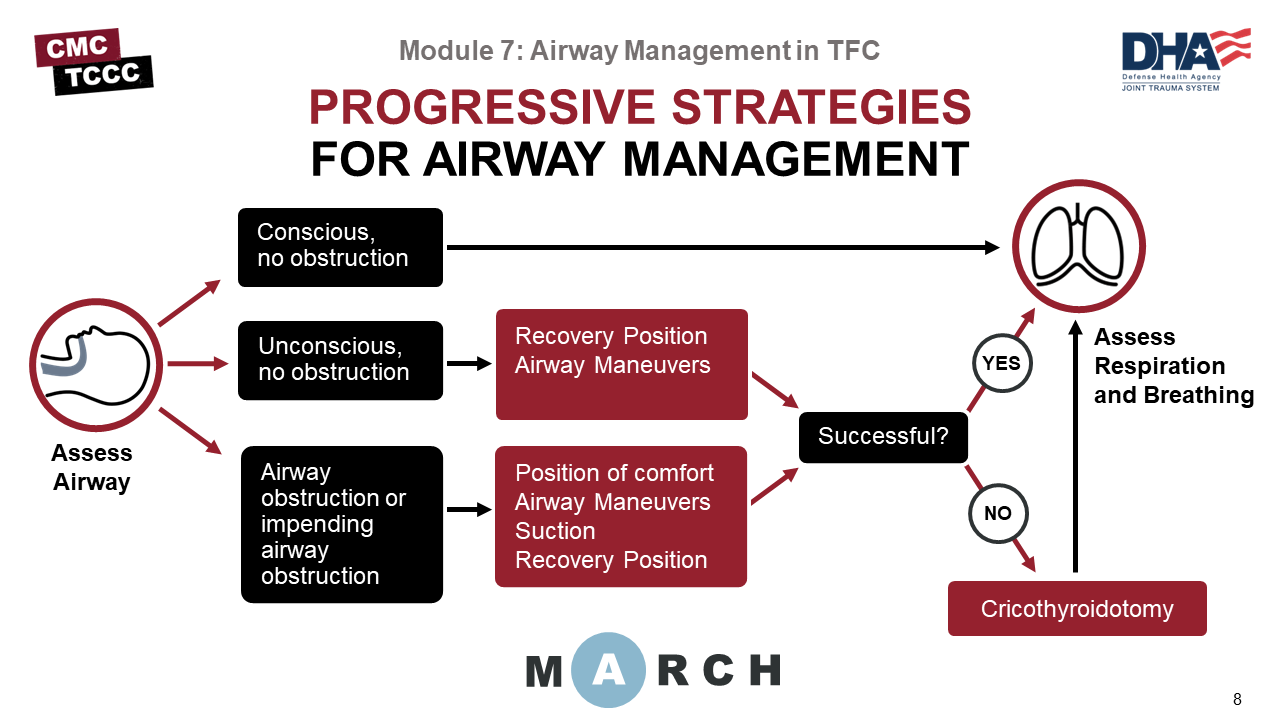

The TCCC Guidelines outline the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC)-recommended approach to airway management. We will review the details of each step and intervention throughout the rest of this module and in the skills stations, but this provides a general overview of the strategy you should adopt in assessing and managing the airway during Tactical Field Care.

If the casualty is conscious and shows no signs of airway obstruction, then proceed to assessing their respiratory status (the “R” in MARCH PAWS).

If the casualty is unconscious (or nearly unconscious), but has no signs of obstruction, then the casualty can be placed in the recovery position, airway can be opened with a head-tilt/chin-lift or jaw-thrust maneuver.

However, if a semi-conscious casualty has an impending or current obstruction, they should be allowed to assume whatever position that best protects the airway, to include sitting up and/or leaning forward, after attempting airway maneuvers. If the casualty becomes unconscious during these interventions, then place them in the recovery position after.

If these actions establish an airway successfully, move to assessing their respiratory status. But if they are not successful, move to establishment of a more advanced airway by performing a cricothyroidotomy before moving on to the respiratory assessment.

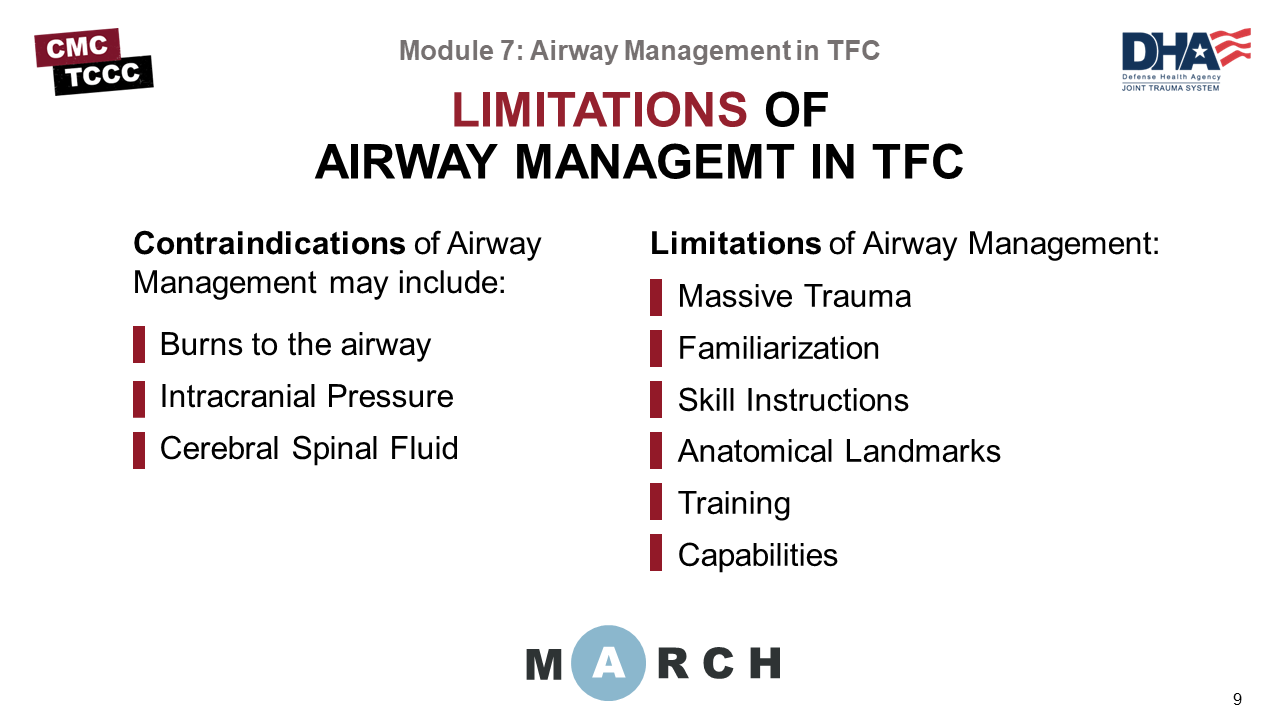

Contraindications of Airway Management may include:

- Burns to the airway – facial burns, singeing of the nasal hairs, or carbonaceous sputum

- Cerebral Spinal Fluid

Limitations of Airway Management:

- Massive Trauma – limited anatomical instruction

- Familiarization – lack of “hands-on” familiarization with laryngeal anatomy

- Skill Instructions – non-standardized step-by-step training in the surgical technique involved

- Anatomical Landmarks – anatomically incorrect training manikins

- Training – lack of standardized refresher training frequency

- Capabilities – Transport time, type of transport (MEDEVAC vs CASEVAC), advanced equipment (ventilator)

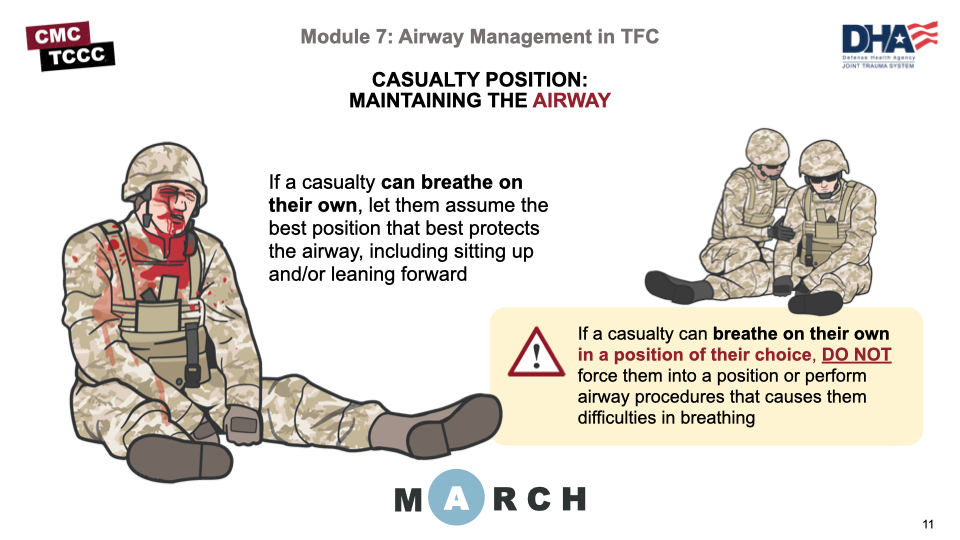

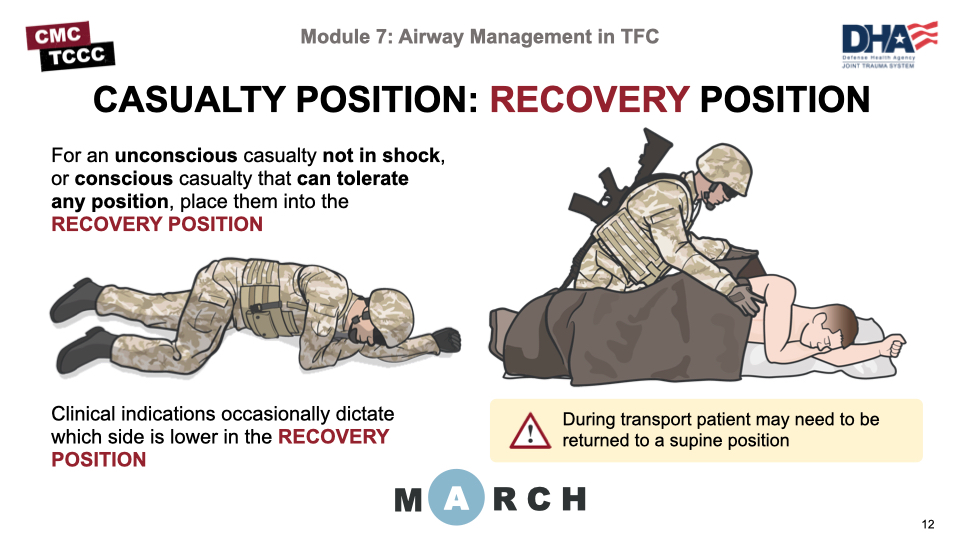

After assessing and appropriately treating any airway compromise, positioning the casualty properly will help maintain a patent airway.

Conscious casualties with maxillofacial trauma should not be forced into the supine position if they are able to breathe more comfortably in the sitting position. If they are able to tolerate the supine position, this will aid in the remainder of the assessment, but if placing supine causes increased distress, minimize the time spent in that position when clinically and tactically feasible.

For some conscious patients, there is a position of maximal comfort they will strive to maintain, and every effort should be made to allow them to do so. However, in other patients, including unconscious patients, no specific position seems to be warranted. In those patients, the recovery position provides a few advantages. By having their heads turned and facing slightly downward, the risk of aspiration due to emesis, heavy secretions, or blood is reduced.

In certain cases, having one side down (such as having the injured side of a chest down) is clinically indicated, but in other cases, either side can be lower, and logistical or patient movement considerations may impact the decision about which side should be lower. During transport, it is often difficult to maintain the recovery position and the patient may need to be returned to a supine position.

This video will go over the steps to follow in placing a casualty in the recovery position. You will be able to practice this during the respiration skill stations.

RECOVERY POSITION TECHNIQUE VIDEO

Unconscious casualties or semi-conscious casualties demonstrating signs of partial obstruction caused by the tongue should have their airways opened with the head-tilt/chin-lift or the jaw-thrust maneuver.

As mentioned previously, muscles of the tongue may have relaxed, causing the tongue to occlude the airway, and using the head-tilt/chin-lift or jaw-thrust maneuver may move the tongue and open the airway, allowing the casualty to resume breathing on their own.

If you suspect that the casualty has suffered a neck or spinal injury, use the jaw-thrust method (if a First Responder is available and able to maintain the jaw-thrust maneuver).

These videos will go over the steps you should take when performing the head-tilt/chin-lift and jaw-thrust maneuvers to open an airway.

HEAD-TILT/CHIN-LIFT MANEUVER VIDEO

JAW THRUST MANEUVER VIDEO

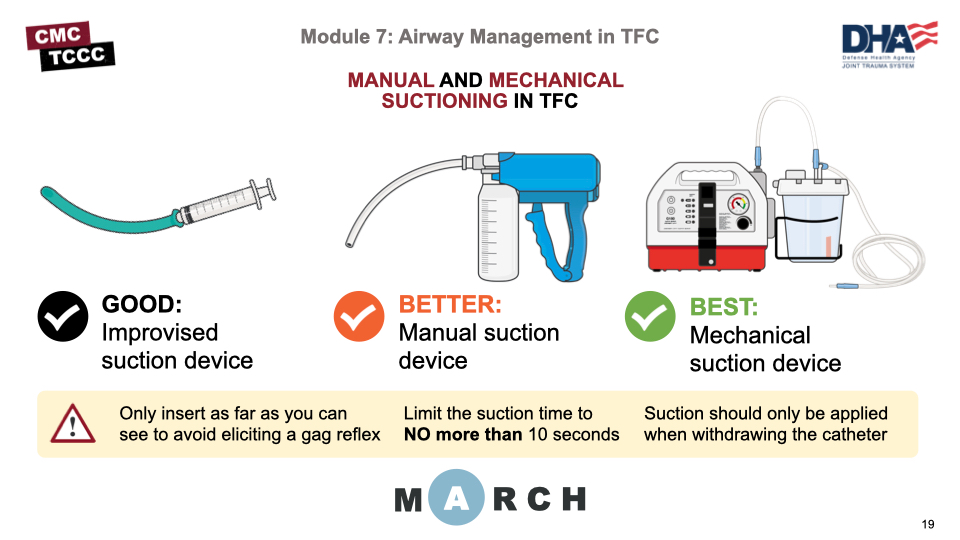

Ideally, suction should be used to remove secretions, mucous, or blood from the airway or oropharynx when establishing and maintaining an airway. The JTS clinical practice guidelines characterize suction devices as:

- Good: an improvised suction (for example, a syringe and a nasopharyngeal airway, and patient positioning if not contraindicated)

- Better: manual suction device

- Best: powered (or battery-operated) commercial mechanical suction device.

Preoxygenate the casualty before suctioning (if possible) for a minimum of 30 seconds and to limit the suction time to NO more than 10 seconds to prevent hypoxia. Also, insert the suction catheter no further than you can visualize, or you may stimulate a gag reflex.

Of note, the suction should only be applied when withdrawing the catheter and not upon initial insertion.

This video will go over the proper techniques for manual suction in clearing an airway.

MANUAL SUCTION VIDEO

This video will go over the proper techniques for mechanical suction in clearing an airway.

MECHANICAL SUCTION VIDEO

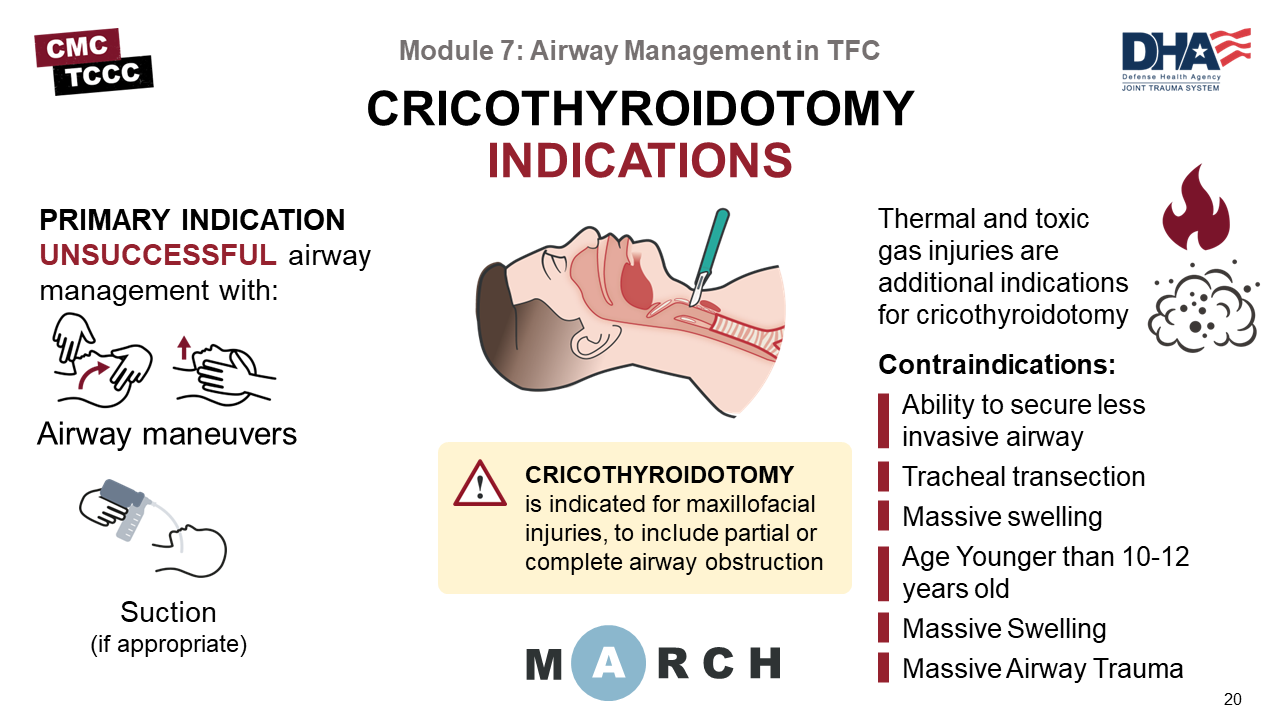

The primary indication for performing a cricothyroidotomy has already been mentioned – an unsuccessful attempt to maintain a patent airway using positioning techniques often in casualties with facial and oral trauma.

Thermal or toxic gas injuries are also important considerations in certain tactical situations and may result in airway edema that can cause an immediate or delayed airway obstruction. Thermal injuries should be suspected if the casualty is exposed to fire in a confined space or if they have facial burns, singeing of the nasal hairs, or carbonaceous sputum. In these cases, cricothyroidotomy is the airway intervention of choice.

Therefore, If the less invasive measures previously discussed are unsuccessful, a surgical airway by cricothyroidotomy is recommended. Cricothyroidotomy has been reported as safe and effective in trauma patients, albeit with occasional complications.

One large study of military prehospital surgical airways showed a 33% procedure failure rate for medics and a 15% failure rate for physicians and physician assistants. Some of that is likely due to the tactical situation where the procedure was performed, but it highlights the need for medics to consistently train and refresh their skills.

The only absolute contraindication to cricothyrotomy is the ability to secure an airway with less invasive means, but this is not always an option in austere environments. Airway trauma that renders cricothyrotomy a hopeless procedure, such as tracheal transection in which the distal end retracts into the mediastinum or a significant cricoid cartilage or laryngeal fracture, can also be absolute contraindications.

Relative contraindications to surgical cricothyrotomy include massive swelling or obesity with loss of landmarks. Age younger than 10 to 12 years is a contraindication because anatomical considerations make surgical cricothyrotomy extremely difficult, children are prone to laryngeal trauma, and they have a higher incidence of postoperative complications from surgical cricothyrotomy than adults. Therefore, children should undergo needle cricothyrotomy if no other airway can be obtained.

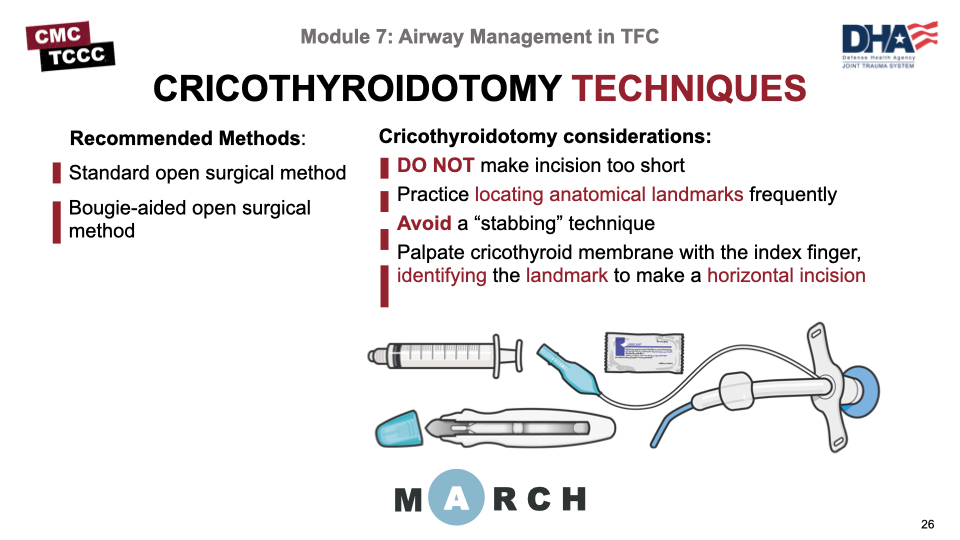

There are several methods for performing a cricothyroidotomy, and CoTCCC research has helped identify which techniques have evidence to support their recommendation for use. Of note, a crossover study comparing the Cric-Key™ with the standard surgical procedure revealed that medics perform the procedure faster and with a lower failure rate using the Cric-Key. For that reason, it is considered the preferred device for cricothyroidotomies. The other two techniques that are CoTCCC-recommended include the bougie-aided open surgical technique and the standard open surgical technique.

Although there are considerations specific to each technique that you will learn about in the upcoming videos, there are some common considerations to highlight.

- The most common error is making the initial incision too small, thereby limiting the ability to clearly visualize the cricothyroid membrane.

- Identifying the landmarks properly is difficult and commonly leads to incorrect placement, including insertion into the trachea above the thyroid cartilage. This is compounded in large and muscular necks, and highlights the need to train frequently and practice landmark identification on multiple anatomical variants, if possible.

- Avoid “stabbing” when incising, as the scalpel can penetrate other structures if you are not careful.

- Once the membrane has been incised, Slide the integrated tracheal hook down the handle with your thumb until it enters the trachea and disengages from the handle, and Insert the Cric-Key with the endotracheal airway into the trachea .

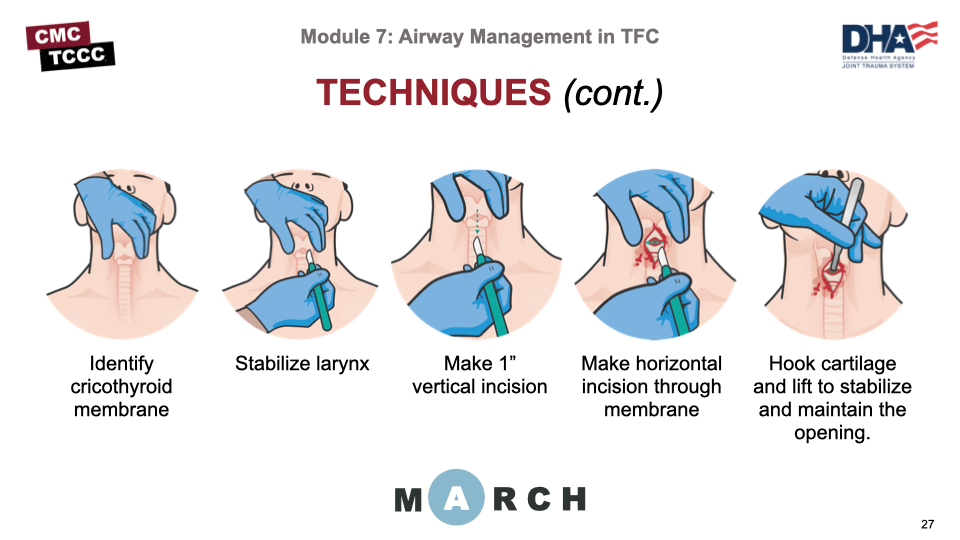

The initial steps of performing a cricothyroidotomy are common to all of the CoTCCC-recommended techniques. They include:

- Identifying the cricothyroid membrane between the thyroid cartilage and the cricoid cartilage

- Holding the trachea with the nondominant hand to stabilize the airway.

- Making a vertical skin incision from the inferior edge of the thyroid cartilage to the top of the cricoid cartilage (incising down to the cricothyroid membrane)

- Dissect the tissues to expose the membrane, and

- Making a horizontal incision through the cricothyroid membrane.

From there, each technique uses a different approach to establishing the airway. Identifying the landmarks properly and exposing the membrane is where most errors occur, and it is important to take advantage of as many training opportunities as you can to improve that skill, including practicing landmark identification on one another. The following are reasons why common errors occur:

- Limited anatomical instruction

- Lack of “hands-on” familiarization with laryngeal anatomy

- Non-standardized step-by-step training in the surgical technique involved

- Anatomically incorrect training manikins

- Lack of standardized refresher training frequency

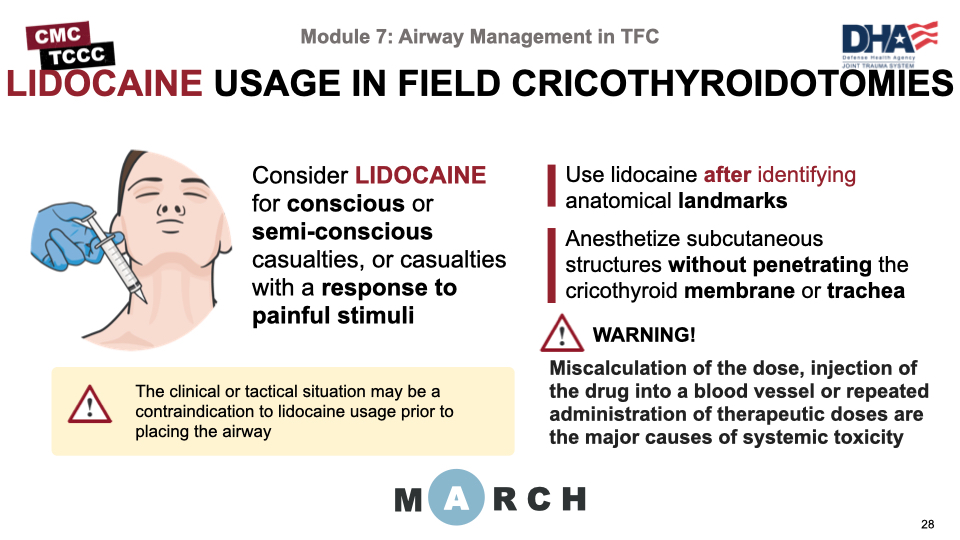

Not all casualties who need a cricothyroidotomy will be unconscious and unresponsive to painful stimuli. If your casualty is conscious, semi-conscious, or has exhibited responses to painful stimuli during the first part of your assessment, and a surgical airway is indicated, consideration should be given to using lidocaine to anesthetize the skin and neck structures prior to the procedure. However, the clinical or tactical situation may be a contraindication to anesthetizing the casualty prior to placing the airway. For example, a complete or near-complete obstruction with impending respiratory arrest should be addressed immediately, even if the casualty is conscious. Likewise, there may be tactical situations that require an immediate response due to time constraints in maintaining a safe environment for you and your casualty. Lidocaine is not always available, as some unit procedures and packing lists do not prioritize lidocaine for the medical aid bag.

When available, lidocaine should be used after identifying the anatomical landmarks and include the skin and the subcutaneous spaces without inserting the needle deep enough to go through the membranes or trachea.

If a patient becomes toxic, neurological symptoms such as dizziness, tinnitus, and peri-oral numbness usually precede cardiovascular manifestations. The most critical aspect of local anesthetic is appropriate dosing. The recommended maximum dose for subcutaneous infiltration of lidocaine without epinephrine is 4.5 milligrams per kilogram (mg/kg) and for lidocaine with epinephrine is 7 mg/kg.

We’ll show three procedural videos in a row, starting with this video demonstrating the procedure for performing a cricothyroidotomy using a Cric-Key.

CRIC-KEY CRICOTHYROIDOTOMY VIDEO

This video demonstrates the procedure for performing a cricothyroidotomy using the bougie-aided open surgical technique.

BOUGIE-AIDED CRICOTHYROIDOTOMY VIDEO

This video demonstrates the procedure for performing a cricothyroidotomy using the standard open surgical technique.

OPEN CRICOTHYROIDOTOMY VIDEO

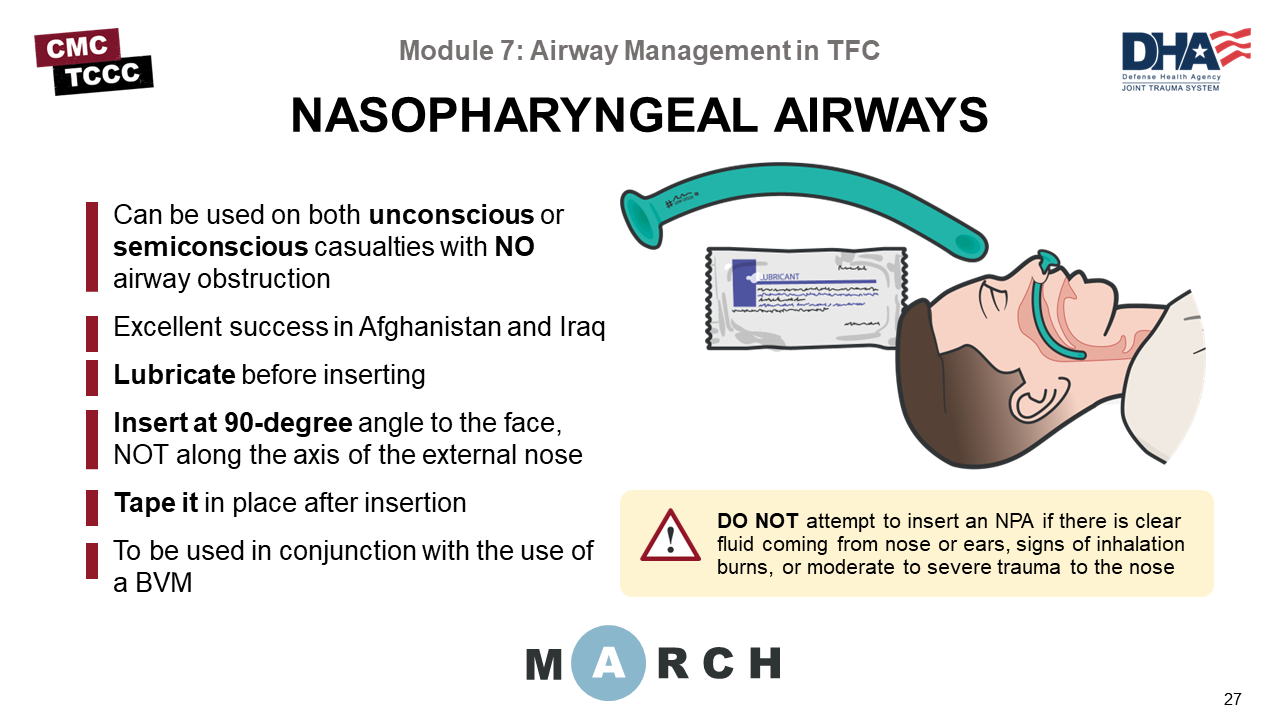

If the casualty has impaired ventilation and uncorrectable hypoxia with decreasing oxygen saturation below 90%, consider insertion of a properly sized Nasopharyngeal Airway, and ventilate using a 1000ml resuscitator Bag-Valve-Mask.

An NPA is better tolerated than an oropharyngeal airway if the casualty regains consciousness and is unlikely to stimulate their gag reflex. Also, a nasopharyngeal airway is less likely to be dislodged during transport.

The NPA should be inserted into the right nostril, if not obstructed, with the bevel towards the nasal septum. If unable to insert into the right nostril, insert into the left nostril. Ensure a water-based lubrication is used (like the one contained within the Joint First Aid Kit, or JFAK). The correct angle for insertion is 90 degrees to the frontal plane of the face – NOT along the long axis of the nose. Although intracranial insertion of NPAs has been rarely reported in the literature, it has not been reported in any casualties from recent operations; nevertheless, the proper angle of insertion will help prevent potential injuries.

Do not use an NPA if there is clear fluid coming from the ears or nose. This may be cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), an indication of a possible skull fracture.

Facial burns, singeing of the nasal hairs, or carbonaceous sputum.

Any obvious deformities to the nose due to trauma is a clear indication to not attempt an NPA insertion.

Allow the conscious casualty to assume whatever position allows them to breathe most comfortably.

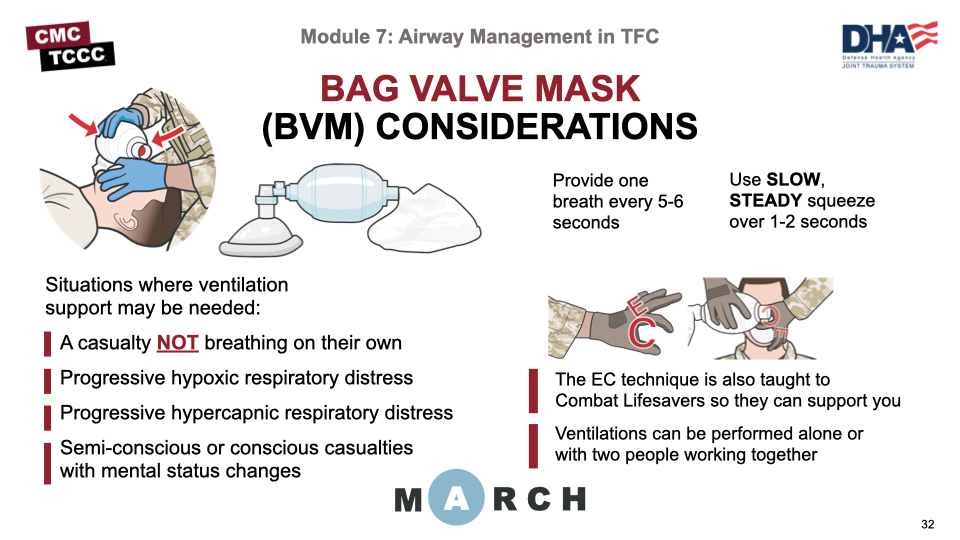

Ventilatory support to casualties may be needed in tactical field situations when the casualty is unable to adequately ventilate for themselves, including unconscious patients who are apneic, patients with progressive hypoxic respiratory distress, progressive hypercapnic respiratory distress, and semi-conscious or conscious patients with mental status changes who cannot protect their airway.

The technique for establishing and maintaining a seal with the mask is often called the EC technique, named after the positioning of the fingers on the hand securing the mask, and will be demonstrated in the video. This is also a skill that is taught to Combat Lifesavers, so they can support you, as needed. Once a seal is established, the casualty should be ventilated every 5-6 seconds (10-12 breaths/minute) using a slow steady squeeze over 1-2 seconds.

When ventilatory support is needed, one of the responders must be dedicated to providing ventilatory support, so without support from a Combat Lifesaver or other trained responder the rest of the casualty assessment and treatment cannot be completed. Therefore, it is important to accurately determine if ventilatory support is necessary in order to preserve your limited resources. For example, just because a patient has undergone a cricothyroidotomy does not mean that they cannot ventilate on their own and must be bagged.

This video demonstrates the insertion of an NPA

NPA Insertion Video

This video demonstrates the procedure for ventilating using a bag valve mask technique.

BAG VALVE MASK TECHNIQUES VIDEO

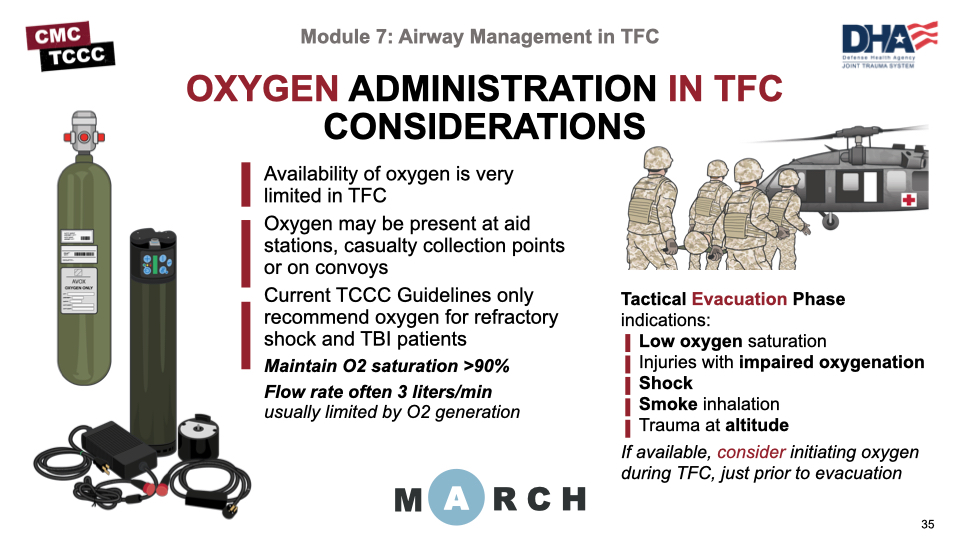

Although combat medics seldom carry oxygen with them due to its weight and potential injuries from the pressurized containers, advances in oxygen generation are moving smaller, safer oxygen resources closer to the battlefield, and oxygen may be found at casualty collection points (CCPs) or with some convoys. Current TCCC Guidelines recommended oxygen use, if available, in patients with signs of refractory shock or TBI patients, with the goal of maintaining an oxygen saturation greater than 90%.

The recommendations for oxygen use expand in the Tactical Evacuation Care phase, to include low oxygen saturation, injuries with impaired oxygenation (like chest wounds or pneumothorax), shock, smoke inhalation, and trauma at altitude. If any of these conditions are present, consideration for initiating supplemental oxygen administration during TFC, prior to evacuation, may be indicated.

Interestingly, studies have demonstrated that trauma casualties not in respiratory distress have worse outcomes when they receive supplemental oxygenation than their counterparts who do not receive oxygen. Therefore, supplementing all trauma casualties is not appropriate, and should be reserved for TBI, shock, or in preparation for Tactical Evacuation Care situations.

When administered, the dose is often 3 liters/min; but that is a function of the production capacity of the generators usually seen in a Tactical Field Care setting. If higher oxygen flows are available, they should be increased to maintain a pulse oximetry reading of more than 90%, particularly in cases of TBI.

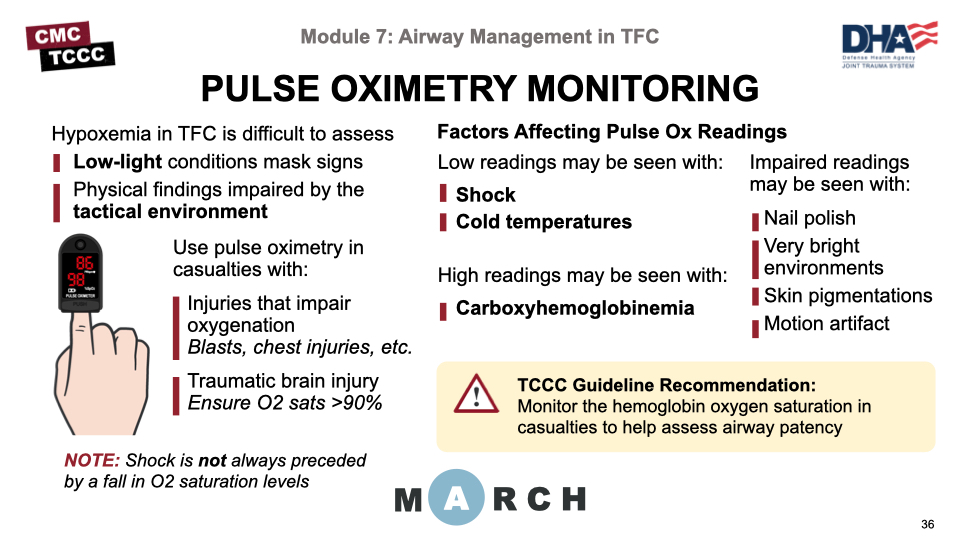

Pulse oximeters are now commonly included in the medical kits carried by CMC and are a useful adjunct to physical examination skills during clinical assessments. Physical findings like cyanosis and pallor are very difficult to assess in low-light operations and hypoxemia can easily be missed.

Normal pulse oximetry, or pulse ox, values are in the high 90s, unless at altitude, in which case they may be significantly lower. For example, a healthy person at 12,000 feet may have a pulse ox in the high 80s. This is an important point to remember during aeromedical evacuations when cabin altitudes may trigger a decrease in the pulse ox readings. Low saturation levels and trends to lower saturations can be indicative of respiratory compromise and should trigger further assessment to rule out life-threatening conditions.

There are several factors that can affect the pulse oximetry readings. Lowered readings can be caused by shock (where the poor perfusion affects the signal and causes a low reading) and cold temperatures (which cause peripheral vasoconstriction with a similar drop in perfusion). On the other hand, carboxyhemoglobin (seen in carbon monoxide poisoning) can cause a falsely elevated reading. And other conditions can interfere with the readings by altering the perceived intensity of the light signal, like very well-lit environments, nail polish, some skin pigmentations, and motion artifact.

Pulse ox monitoring should be initiated in casualties who are unconscious or who have injuries associated with impaired oxygenation (like blast injuries, chest contusion, and penetrating injuries of the chest). It should also be used to monitor casualties who have TBI, in order to ensure that their oxygen saturations remain above 90%, as hypoxemia will worsen their clinical outcomes.

Keep in mind that saturation levels may not signal impending shock, as good hemoglobin oxygen saturations may be seen in casualties shortly before they go into hypovolemic shock. Also, if a casualty has obvious signs of airway obstruction, tension pneumothorax, or hemorrhage, their treatment should not be delayed to establish pulse oximetry.

Airway management in TFC involves a significant understanding of many issues and the development of competency in performing several skills.

The topics that we covered included, amongst others:

- Identification of the signs of an airway obstruction,

- Considerations for spinal immobilization,

- Progressive strategies for airway management,

- Indications for an advanced airway,

- Considerations for using oxygen and the importance of pulse oximetry

The skills that were taught and practiced include:

- Airway maneuvers (using a head-tilt/chin-lift or jaw-thrust method) and placing the casualty in the recovery position

- Manual and mechanical suctioning

- Establishing an airway by cricothyroidotomy, and

- Ventilating using a bag valve mask with NPA

Together, the knowledge and skills learned from this module will prepare you to manage airways in the Tactical Field Care environment.

To close out this module, check your learning with the questions below (answers under the image).

Answers

What are the signs of an airway obstruction?

In cases of partial or complete airway obstruction, the casualty may experience agitation, cyanosis, confusion or even unconsciousness, difficulty breathing (dyspnea), or high-pitched breathing noises such as stridor, wheezing, snoring, or gurgling sounds.

What is the best position for a conscious casualty that is breathing on their own?

Allow the conscious casualty that is breathing on their own to assume whatever position allows them to breathe most comfortably.

What are common errors when performing a cricothyroidotomy?

The most common error is making the initial incision too small, thereby limiting the ability to clearly visualize the cricothyroid membrane; identifying the landmarks properly is difficult and commonly leads to incorrect placement; “stabbing” when incising; not inserting a finger, once the membrane has been incised, to manually feel for the lumen and tracheal rings.

What condition warrants oxygenation in TFC according to the TCCC Guidelines?

Traumatic brain injury; maintain an oxygen saturation >90%