K9 Clinical Practice Guideline #6- Shock Management

K9 Combat Casualty Care Committee

Introduction

- These clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) apply to deployed human healthcare providers (HCPs) in combat or austere areas of operations. Veterinary care is established at multiple locations throughout theater, and the veterinary health care team is the MWD’s primary provider. However, HCPs are often the only medical personnel available to MWDs that are critically ill or injured. The reality is that HCPs will routinely manage working dogs in emergencies before they are ever seen by veterinary personnel.

- Care by HCPs is limited to circumstances in which the dog is too unstable to transport to supporting veterinary facilities or medical evacuation is not possible due to weather or mission constraints; immediate care is necessary to preserve life, limb, or eyesight; and veterinary personnel are not available. HCPs should only perform medical or surgical procedures – within the scope of their training or experience – necessary to manage problems that immediately threaten life, limb, or eyesight, and to prepare the dog for evacuation to definitive veterinary care. Routine medical, dental, or surgical care is not to be provided by HCPs.

- Emergent surgical management of injured MWDs may be necessary by HCPs to afford a chance at patient survival. This should be considered only if:

- The provider has the necessary advanced surgical training and experience.

- The provider feels there is a reasonable likelihood of success.

- The provider has the necessary support staff, facilities, and monitoring and intensive care facilities to manage the post-operative MWD without compromising human patient care.

- Emergent surgical management should be considered only in Role 2 or higher medical facilities and by trained surgical specialists with adequate staff. Direct communication with a US military veterinarian is essential before considering surgical management, and during and after surgery, to optimize outcome.

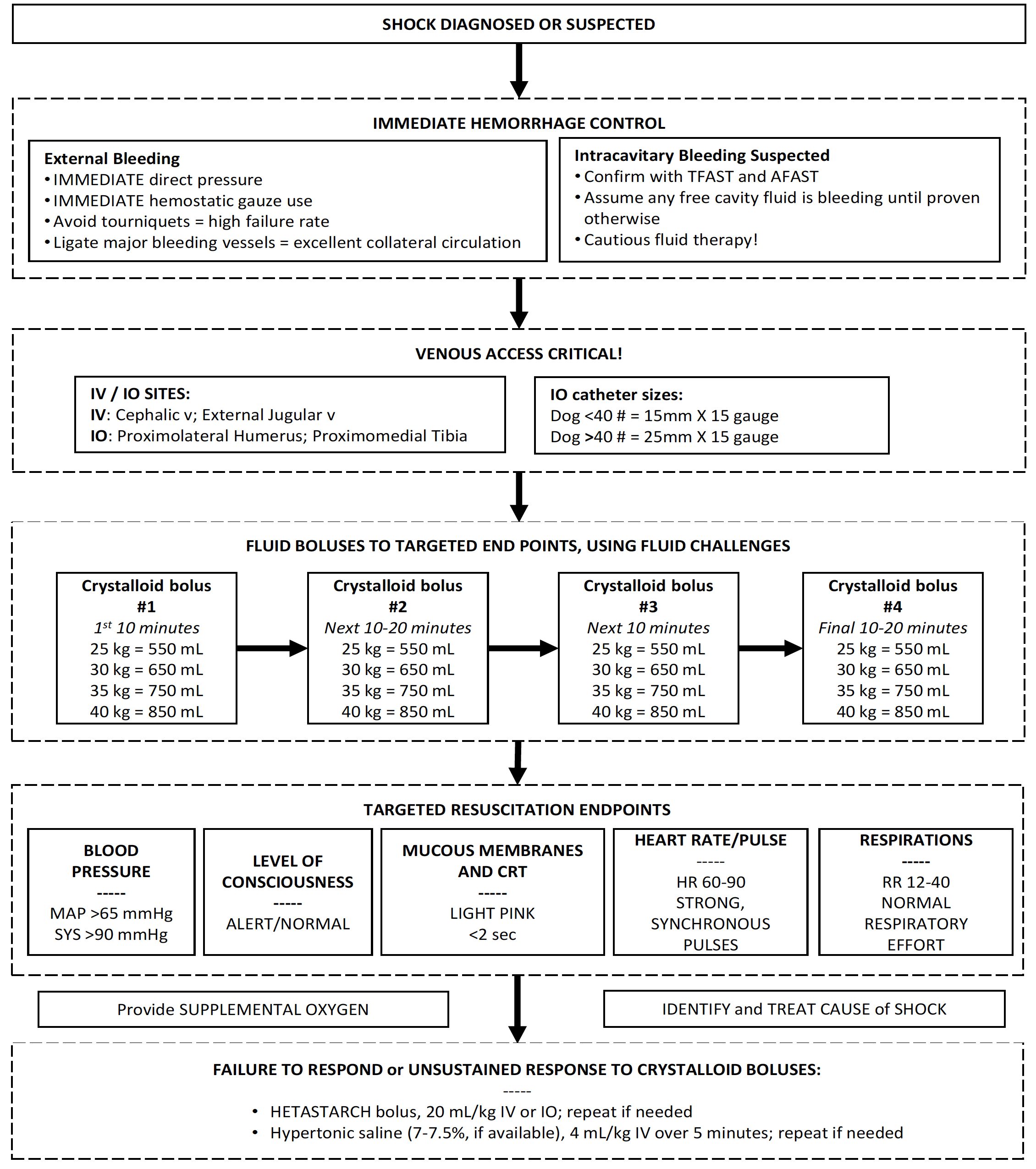

Causes of Shock

Shock in deployed MWDs will most likely be due to hemorrhage from trauma or hypovolemia due to heat injury or gastrointestinal losses. Control bleeding (if present) and then stabilize the patient using targeted fluid therapy. Figure 33 provides a clinical management algorithm for shock management in MWDs.

Clinical Management Algorithm for Shock Resuscitation in MWDs.

Figure 33. Clinical Management Algorithm for Shock Resuscitation in MWDs.

Immediate Hemorrhage Control

Treatment by handlers and combat medics may have been performed, with varying degrees of success.1,2 Expect dogs to arrive with pressure dressings, hemostatic gauze packed into wounds, and improvised tourniquets. Expect untreated or inadequately treated extremity hemorrhage, and suspect “hidden” intracavitary hemorrhage in the chest and abdomen.

- Assess for unrecognized hemorrhage and control all sources of external bleeding. Use direct pressure initially, or rapidly clamp and ligate major vessels if traumatized. Dogs have excellent collateral circulation, and paired major vessels can be ligated without concern for tissue ischemia or edema, to include the femoral arteries and veins, external jugular veins, external carotid arteries, and brachial arteries and veins.3,4

- Tourniquets are unreliable on the limbs of dogs due to the anatomic shape of the leg. Conventional human tourniquets do not remain in place or effectively control hemorrhage. Some success is reported in use of improvised tourniquets, such as surgical rubber tubing or constrictive gauze bandage. If delay in definitive care of major extremity trauma is expected, use hemostatic agents, direct pressure, and compressive bandaging to assist with hemorrhage control.

- Use thoracic FAST (TFAST) and abdominal FAST (AFAST) to rapidly scan for intracavitary fluid (See CPG 4 and CPG 7).5,6 Assume intracavitary fluid is due to bleeding until proven otherwise.

Clinical Signs of Shock in MWDs

Dogs in shock are amazing in how stable they appear on initial presentation, due to compensatory mechanisms.

- MWDs in early (compensatory) shock may have tachycardia, tachypnea, alert mentation, rapid arterial pulses with a normal or increased pulse pressure, decreased capillary refill time (< 2 seconds), and normal or bright red mucous membranes. While this MWD seems normal, it is already in compensatory shock. Immediate treatment at this point may stop the progression of shock.

- As the early decompensatory phase of shock begins, tachycardia persists, pulse pressure and quality begins to drop or may be normal, capillary refill time becomes prolonged, mucous membranes appear pale or blanched, peripheral body temperature drops, and mental depression develops. Aggressive treatment must be provided to halt ongoing shock.

- As late decompensatory shock develops, the heart rate drops despite a decreased cardiac output, capillary refill time is very prolonged or absent, pulses are poor or absent, both peripheral and core temperature is very low, and marked mental depression (stupor) is present. Irreversible cellular injury may be present to such a severe degree that despite aggressive measures at this point, many patients will die.

Standard Shock Therapy

Provide immediate fluid therapy targeted to specific endpoints, provide supplemental oxygen, and identify and treat the cause for the shock. Tranexamic acid (TXA) or ɛ-aminocaproic acid (EACA) may be helpful in dogs with catastrophic hemorrhage.

1. Place multiple large-bore IV or IO catheters or perform venous cut-down.

- Do not delay in placing catheters. The IO route is rapid, reliable and safe — USE IT! Place peripheral or central lines when feasible. If one percutaneous attempt is not successful in a shock patient, immediately choose an alternate percutaneous site and also begin an immediate venous cutdown or perform IO catheterization. The cephalic veins and external jugular veins are ideal for peripheral catheterization.

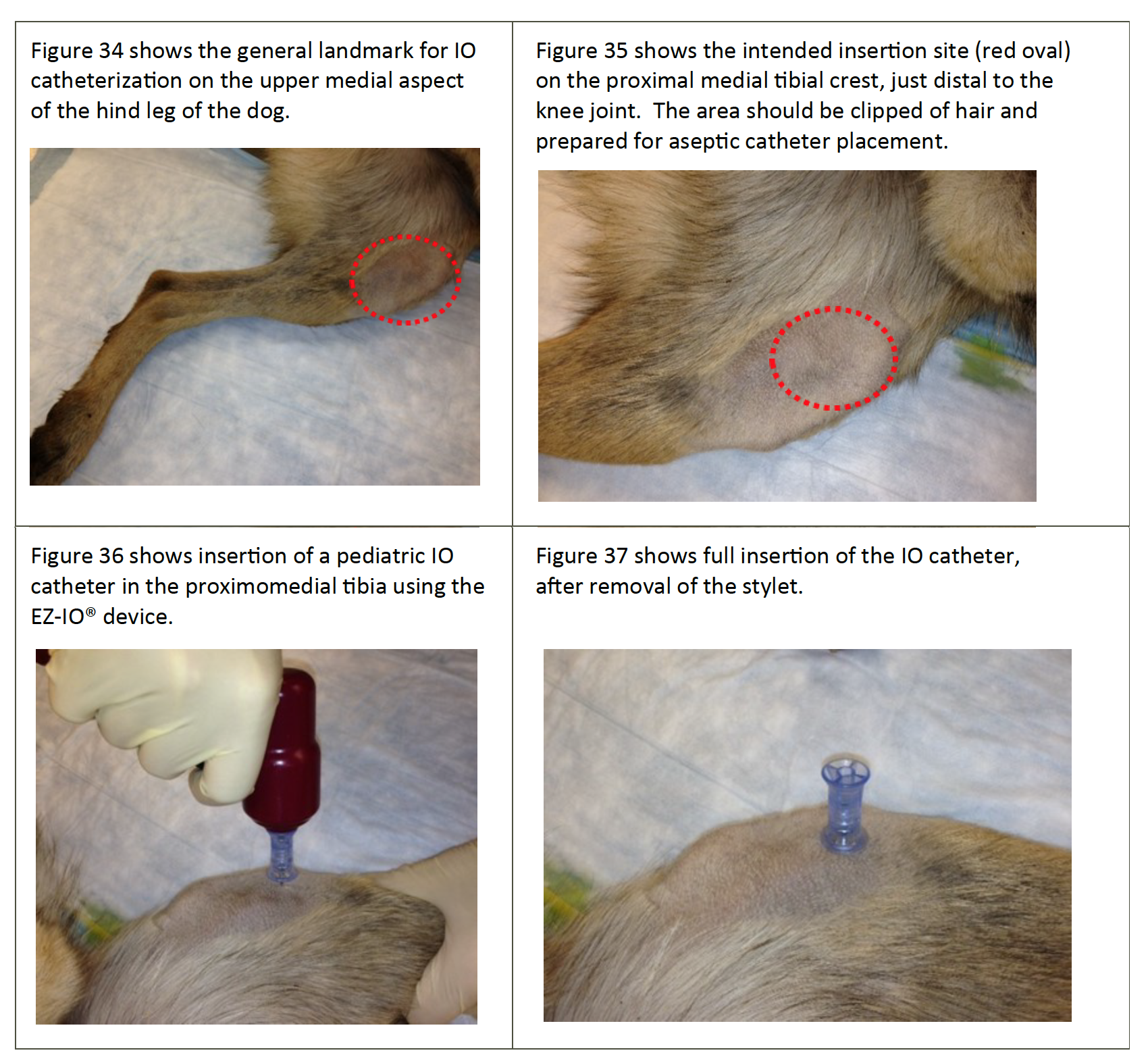

- The proximal cranial medial tibia and the proximal lateral humerus are ideal for IO catheter placement, using the same technique as for people (See Figures 34-37). Most MWDs weigh >40#, so use adult (25mm X 15 gauge) IO catheters. Use pediatric (15mm X 15 gauge) IO catheters in dogs weighing less than 40#.

Figures 34-37. Intra-osseous Catheter Placement (Tibia) in a MWD.

Note: Sterile draping is removed to provide better visualization; perform catheterization using sterile technique.

2. Give crystalloid fluids as the first-line treatment.9-14

- Normosol-R® or Plasmalyte-A® are optimal for dogs; however, saline or LRS are acceptable in emergent cases.

- Crystalloid fluid challenges, as needed based on response to therapy, are better than large volume fluid administration.11-13 Be prepared to administer up to 90 mL/kg of crystalloids in the first hour (1 blood volume for the dog). Aggressive, but careful, fluid delivery, with frequent reassessment of the patient‘s status, is critical. Most MWDs can be resuscitated with much less than this calculated maximum volume.

- For quick reference, ADD a ZERO to the dog’s body weight (in pounds) to approximate a safe but effective bolus volume. For example, a 45# dog would need about a 450 mL bolus, and a 75# dog would need about 750 mL as a bolus.

3. Use synthetic colloids and hypertonic saline (HTS) in dogs with refractory shock. Very limited data in dogs suggest increased risks,15-18 but dogs do not seem as sensitive to the adverse effects of these fluids as are people. Two recent studies in dogs showed no adverse side effects, specifically acute kidney injury, with tetrastarch use.19,20 The benefits outweigh the risks, so be aggressive with synthetic colloid and HTS.15-17

- Give hydroxyethyl starch (HES) as an IV or IO bolus of 10-20 mL/kg total over 5-10 minutes if clinical signs of shock do not abate after the first 30 minutes or the first 2 bolus crystalloid challenges), or response to crystalloid challenges is not sustained.11-13,15,20,21 Repeat this bolus if no response to therapy.

- Use HTS IV boluses, if 7.0 - 7.5% HTS is available, for MWDs that fail to respond to 2 or 3 boluses of crystalloids and/or 1 or 2 boluses of HES. Give 4 mL/kg over 5 minutes.11-13,20 Do not administer HTS by the IO route.

4. Human serum albumin (HSA) use. Do not give HSA or other synthetic colloids (e.g., dextrans) to MWDs, because severe allergic reactions are possible (HSA) and coagulopathies are common (dextrans). Some data suggest benefit in a very limited subset of patients with severe hypoalbuminemia,22,23 but risks far outweigh potential benefit in dogs with shock.

5. Blood product use. Canine blood products are not available for immediate HCP use.2 Dogs cannot be transfused with human blood products. HCPs will have to manage hemorrhagic shock with crystalloid and colloid therapy.

6. Tranexamic acid (TXA) and ɛ-aminocaproic acid (EACA) use. There is limited, but promising, data to guide use of TXA24-27 and EACA28 in dogs with hemorrhage. Dogs appear to be hyperfibrinolytic compared to humans, suggesting higher doses of TXA may be needed in dogs. Consider TXA or EACA if the dog is anticipated to need significant blood transfusion, such as severe hemorrhagic shock, limb amputation, penetrating torso trauma with severe non-compressible bleeding, because canine blood products are not available. Administer these drugs as soon as possible after trauma, but NO LATER THAN 3 HOURS post injury.

- TXA: 10 mg/kg in 100 mL NS or LRS, IV over 15 min.

- EACA: 150 mg/kg in 100 mL NS or LRS, IV over 15 min.

- If bleeding continues, a CRI of additional TXA at 10 mg/kg/hour for 3 hours can be administered.

7. Targeted shock resuscitation end points that are practical for HCPs include systolic and mean arterial pressures, level of consciousness and mentation, mucous membrane color and capillary refill time, HR, RR, and pulse quality.

- Target a MAP >65 mmHg or a Sys >90 mmHg. Note that neonatal or pediatric blood pressure cuffs must be used (See CPG 2).

- Target normal level of consciousness (LOC) and an alert mentation.

- Target light pink-to-salmon pink MM and a CRT <2 seconds.

- Target a HR that is 60-90 beats per minute at rest with a strong, synchronous pulse quality.

- Target a respiratory rate at rest of 12-40 breaths per minute with normal effort.

- Once shock has abated, continue IV crystalloid fluids at 3-5 mL/kg/hour for 12-24 hours to maintain adequate intravascular volume.

8. Provide supplemental oxygen therapy. Oxygen supplementation is critical. Every shock patient should receive supplemental oxygen therapy until stable (See CPG 3).

9. Identify and treat the cause of shock. The cause of shock must be corrected, if possible.

- Patients with massive intra-abdominal or intrathoracic bleeding need surgery to find the site of bleeding and surgically correct the loss of blood, with the caveats in mind as discussed previously.

- CPG 4 addresses emergent resuscitative thoracotomy. CPG 7 addresses emergent abdominal laparotomy.

- Euthanasia should be considered to prevent undue suffering for a MWD for which emergent surgery is deemed necessary but cannot be performed or has proven unsuccessful (See CPG 21).

References

- Baker JL, Havas KA, Miller LA, et al. Gunshot wounds in military working dogs in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom: 29 cases (2003-2009). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2013;23:47-52.

- Giles III, JT. Role of human health care providers and medical treatment facilities in military working dog care and accessibility difficulties with military working dog blood products. US Army Medical Department Journal April-September 2016:157-160. Available at http://www.cs.amedd.army.mil/amedd_journal.aspx, accessed 29 September 2016, pp 157-160.

- Coffman JD. Peripheral collateral blood flow and vascular reactivity in the dog. J Clin Investigation 1966;45:923-931.

- Whisnant JP, Millikan CH, Wakim KG, et al. Collateral circulation to the brain of the dog following bilateral ligation of the carotid and vertebral arteries. Am J Physiol 1956;186:275-277.

- Lisciandro GR, Lagutchik MS, Mann KA, et al. Evaluation of a thoracic focused assessment with sonography for trauma (TFAST) protocol to detect pneumothorax and concurrent thoracic injury in 145 traumatized dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2008;18:258-269.

- Lisciandro GR, Lagutchik MS, Mann KA, et al. Evaluation of an abdominal fluid scoring (AFS) system determined using abdominal focused assessment with sonography for trauma (AFAST) in 101 dogs with motor vehicle trauma. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2009;19:426-437.

- Raffe MR, Wingfield WE. Hemorrhage and hypovolemia. In: The Veterinary ICU Book. Wingfield WE and Raffe MR, eds. Jackson Hole: Teton New Media, 2002;453-478.

- Crowe DT, Jr., Devey JJ. Assessment and management of the hemorrhaging patient. Vet Clin N Am (Small Anim Pract), 1994;24:1095-1122.

- Kovacic JP. Management of life-threatening trauma. Vet Clin N Am Small Anim Pract 1994;24:1057-1094.

- Drobatz K. Triage and initial assessment. In: Manual of Canine and Feline Emergency and Critical Care. King L and Hammond R, eds. British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 1999;1-7.

- Balakrishnan A, Silverstein D. Shock fluids and fluid challenge. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K, eds. Small Animal Critical Care Medicine. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2015;321-327.

- De Laforcade A, Silverstein D. Shock. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K, eds. Small Animal Critical Care Medicine. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2015;26-30.

- Liu D, Silverstein D. Crystalloids, colloids, and hemoglobin-based oxygen carrying solutions. In: Silverstein DC and Hopper K, eds. Small Animal Critical Care Medicine. St. Louis: Saunders/Elsevier, 2015;311-316.

- Hanel RM, Palmer L, Baker J, et al. Best practice recommendations for prehospital veterinary care of dogs and cats. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2016;26:166-233.

- Glover PA, Rudloff E, Kirby R. Hydroxyethyl starch: a review of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, current products, and potential clinical risks, benefits, and use. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2014;24:642-661.

- Adamik KN, Yozova ID, Regenscheit N. Controversies in the use of hydroxyethyl starch solutions in small animal emergency and critical care. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2015;25:20-47.

- Wurlod VA, Howard J, Francey T, et al. Comparision of the in vitro effects of saline, hypertonic hydroxyethyl starch, hypertonic saline, and two forms of hydroxyethyl starch on whole blood coagulation and platelet function in dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2015;25:474-487.

- Hayes G, Benedicenti L, Mathews K. Retrospective cohort study on the incidence of acute kidney injury and death following hydroxyethyl starch (HES 10% 250/0.5/5:1) administration in dogs (2007-2010). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2016;26:35-40.

- Sigrist NE, Kalin, N, Dreyfus A. Changes in serum creatinine concentration and acute kidney injury (AKI) grade in dogs treated with hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 from 2013 to 2015. J Vet Intern Med 2017;31:434-441.

- Yozova ID, Howard J, Adamik KN. Retrospective evaluation of the effects of administration of tetrastarch (hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4) on plasma creatinine concentration in dogs (2010-2013): 201 dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2016;26:568-577.

- Hammond TN, Holm JL, Sharp CR. A pilot comparison of limited versus large fluid volume resuscitation in canine spontaneous hemoperitoneum. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2014; 50:159–166.

- Gauthier V, Holowaychuk MK, Kerr CL, et al. Effect of synthetic colloid administration on hemodynamic and laboratory variables in healthy dogs and dogs with systemic inflammation. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2014; 24:251-258.

- Vigano F, Perissinotto L, Bosco VRF. Administration of 5% human serum albumin in critically ill small animal patients with hypoalbuminemia: 418 dogs and 170 cats (1994-2008). J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2010;20:237-243.

- Mathews KA, Barry M. The use of 25% human serum albumin: outcome and efficacy in raising serum albumin and systemic blood pressure in critically ill dogs and cats. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2005;15:110-118.

- Fletcher DJ, Blackstock KJ, Epstein K, et al. Evaluation of tranexamic acid and ɛ-aminocaproic acid concentrations required to inhibit fibrinolysis in plasma of dogs and humans. Am J Vet Res 2014;75:731-738.

- Kelmer E, Marer K, Bruchim Y, et al. Retrospective evaluation of the safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid (Hexakapron®) for the treatment of bleeding disorders in dogs. Israel J Vet Med 2013;68:94-100.

- Kelmer E, Segev G, Papashvilli V, et al. Effects of IV administration of tranexamic acid on hematological, hemostatic, and thromboelastographic analytes in healthy adult dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2015;25:495-501.

- Marin LM, Iazbik MC, Zaldivar-Lopez S, et al. Epsilon aminocaproic acid for the prevention of delayed postoperative bleeding in retired racing greyhounds undergoing gonadectomy. Vet Surg 2012;41:594-603.